47. Battle of Cheriton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LANSDOWN BATTLE and CAMPAIGN Lansdown Hill 5Th July

LANSDOWN BATTLE AND CAMPAIGN Information from The UK Battlefields Resource Centre Provided by The Battlefields Trust http://battlefieldstrust.com/ Report compiled by: Glenn Foard: 29/05/2004 Site visit: 21/05/2004 Lansdown Hill 5th July 1643 By late May 1643 Sir William Waller’s army, based around Bath, was parliament’s main defence against the advance out of the South West of a royalist army under Sir Ralph Hopton. After several probing moves to the south and east of the city, the armies finally engaged on the 5th July. Waller had taken a commanding position on Lansdown Hill. He sent troops forward to skirmish with the royalist cavalry detachments and finally forced the royalists to deploy and then to engage. After initial success on Tog Hill, a mile or more to the north, his forces were eventually forced to retreat. Now Hopton took the initiative and made direct and flanking attacks up the steep slopes of Lansdown Hill. Despite heavy losses amongst the regiments of horse and foot in the centre, under musket and artillery fire, the royalists finally gained a foothold on the scarp edge. Repeated cavalry charges failed to dislodge them and Waller was finally forced to retire, as he was outflanked by attacks through the woods on either side. He retreated a few hundred yards to the cover of a wall across the narrowest point of the plateau. As darkness fell the fire-fight continued. Neither army would move from the cover they had found and both armies contemplated retreat. Late that night, under the cover of darkness, it was the parliamentarians who abandoned their position. -

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets the Tower Was the Seat of Royal

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets The Tower was the seat of Royal power, in addition to being the Sovereign’s oldest palace, it was the holding prison for competitors and threats, and the custodian of the Sovereign’s monopoly of armed force until the consolidation of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in 1805. As such, the Tower Hamlets’ traditional provision of its citizens as a loyal garrison to the Tower was strategically significant, as its possession and protection influenced national history. Possession of the Tower conserved a foothold in the capital, even for a sovereign who had lost control of the City or Westminster. As such, the loyalty of the Constable and his garrison throughout the medieval, Tudor and Stuart eras was critical to a sovereign’s (and from 1642 to 1660, Parliament’s) power-base. The ancient Ossulstone Hundred of the County of Middlesex was that bordering the City to the north and east. With the expansion of the City in the later Medieval period, Ossulstone was divided into four divisions; the Tower Division, also known as Tower Hamlets. The Tower Hamlets were the military jurisdiction of the Constable of the Tower, separate from the lieutenancy powers of the remainder of Middlesex. Accordingly, the Tower Hamlets were sometimes referred to as a county-within-a-county. The Constable, with the ex- officio appointment of Lord Lieutenant of Tower Hamlets, held the right to call upon citizens of the Tower Hamlets to fulfil garrison guard duty at the Tower. Early references of the unique responsibility of the Tower Hamlets during the reign of Bloody Mary show that in 1554 the Privy Council ordered Sir Richard Southwell and Sir Arthur Darcye to muster the men of the Tower Hamlets "whiche owe their service to the Towre, and to give commaundement that they may be in aredynes for the defence of the same”1. -

Bills of Attainder

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 2016 Bills of Attainder Matthew Steilen University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Matthew Steilen, Bills of Attainder, 53 Hous. L. Rev. 767 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE BILLS OF ATTAINDER Matthew Steilen* ABSTRACT What are bills of attainder? The traditional view is that bills of attainder are legislation that punishes an individual without judicial process. The Bill of Attainder Clause in Article I, Section 9 prohibits the Congress from passing such bills. But what about the President? The traditional view would seem to rule out application of the Clause to the President (acting without Congress) and to executive agencies, since neither passes bills. This Article aims to bring historical evidence to bear on the question of the scope of the Bill of Attainder Clause. The argument of the Article is that bills of attainder are best understood as a summary form of legal process, rather than a legislative act. This argument is based on a detailed historical reconstruction of English and early American practices, beginning with a study of the medieval Parliament rolls, year books, and other late medieval English texts, and early modern parliamentary diaries and journals covering the attainders of Elizabeth Barton under Henry VIII and Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford, under Charles I. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The militia of London, 1641-1649 Nagel, Lawson Chase The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 THE MILITIA OF LONDON, 16Lf].16Lt9 by LAWSON CHASE NAGEL A thesis submitted in the Department of History, King' a Co].].ege, University of Lox4on for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1982 2 ABSTBAC The Trained Bands and. -

[Note: This Series of Articles Was Written by Charles Kightly, Illustrated by Anthony Barton and First Published in Military Modelling Magazine

1 [Note: This series of articles was written by Charles Kightly, illustrated by Anthony Barton and first published in Military Modelling Magazine. The series is reproduced here with the kind permission of Charles Kightly and Anthony Barton. Typographical errors have been corrected and comments on the original articles are shown in bold within square brackets.] Important colour notes for modellers, this month considering Parliamentary infantry, by Charles Kightly and Anthony Barton. During the Civil Wars there were no regimental colours as such, each company of an infantry regiment having its own. A full strength regiment, therefore, might have as many as ten, one each for the colonel's company, lieutenant-colonel's company, major's company, first, second, third captain's company etc. All the standards of the regiment were of the same basic colour, with a system of differencing which followed one of three patterns, as follows. In most cases the colonel's colour was a plain standard in the regimental colour (B1), sometimes with 2 a motto (A1). All the rest, however, had in their top left hand corner a canton with a cross of St. George in red on white; lieutenant-colonels' colours bore this canton and no other device. In the system most commonly followed by both sides (pattern 1) the major's colour had a 'flame' or 'stream blazant' emerging from the bottom right hand corner of the St. George (A3), while the first captain's company bore one device, the second captain's two devices, and so on for as many colours as there were companies. -

BATTLE FIELD A31 Cheriton WALK 11 A272

River Itchen River River Test River © Winchester City Council 2018. Council City Winchester © Winchester Castle ruins Castle Winchester visitwinchester.co.uk or e-mail [email protected] e-mail or contact the tourist information centre on 01962 840 500 500 840 01962 on centre information tourist the contact If you would like this leaflet in a larger format please please format larger a in leaflet this like would you If who shaped our nation. our shaped who www.battlefieldstrust.com the Cheriton Battlefield, tracing the movements of the soldiers soldiers the of movements the tracing Battlefield, Cheriton the www.visitwinchester.co.uk embark on the walk taken by the troops on 29 March 1644 to to 1644 March 29 on troops the by taken walk the on embark onto log information further For made unusable. made sets out from the Parliamentarian camp at Hinton Ampner and and Ampner Hinton at camp Parliamentarian the from out sets 1644. in War Civil English the during on 5 October 1645 and soon after was blown up and and up blown was after soon and 1645 October 5 on that helped shape the future of England. Follow this trail that that trail this Follow England. of future the shape helped that battlefield and of the events that unfolded across Hampshire Hampshire across unfolded that events the of and battlefield Royalist hands. The castle was taken by Oliver Cromwell Cromwell Oliver by taken was castle The hands. Royalist Civil War and resulted in an important Parliamentarian victory victory Parliamentarian important an in resulted and War Civil -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Doctor of Philosophy MILITARY INTELLIGENCE OPERATIONS IN THE FIRST ENGLISH CIVIL WAR 1642 – 1646 By John Edward Kirkham Ellis This thesis sets out to correct the current widely held perception that military intelligence operations played a minor part in determining the outcome of the English Civil War. In spite of the warnings of Sir Charles Firth and, more recently, Ronald Hutton, many historical assessments of the role played by intelligence-gathering continue to rely upon the pronouncements made by the great Royalist historian Sir Edward Hyde, earl of Clarendon, in his History of the Rebellion. Yet the overwhelming evidence of the contemporary sources shows clearly that intelligence information did, in fact, play a major part in deciding the outcome of the key battles that determined the outcome of the Civil War itself. -

BATTLE FIELD A31 Cheriton WALK 11 A272

© Winchester City Council 2018. Council City Winchester © Winchester Castle ruins Castle Winchester visitwinchester.co.uk or e-mail [email protected] e-mail or contact the tourist information centre on 01962 840 500 500 840 01962 on centre information tourist the contact If you would like this leaflet in a larger format please please format larger a in leaflet this like would you If who shaped our nation. our shaped who www.battlefieldstrust.com the Cheriton Battlefield, tracing the movements of the soldiers soldiers the of movements the tracing Battlefield, Cheriton the www.visitwinchester.co.uk embark on the walk taken by the troops on 29 March 1644 to to 1644 March 29 on troops the by taken walk the on embark onto log information further For made unusable. made sets out from the Parliamentarian camp at Hinton Ampner and and Ampner Hinton at camp Parliamentarian the from out sets 1644. in War Civil English the during on 5 October 1645 and soon after was blown up and and up blown was after soon and 1645 October 5 on that helped shape the future of England. Follow this trail that that trail this Follow England. of future the shape helped that battlefield and of the events that unfolded across Hampshire Hampshire across unfolded that events the of and battlefield Royalist hands. The castle was taken by Oliver Cromwell Cromwell Oliver by taken was castle The hands. Royalist Civil War and resulted in an important Parliamentarian victory victory Parliamentarian important an in resulted and War Civil of a programme of activities explaining -

'He Would Not Meddle Against Newark…' Cromwell's Strategic Vision 1643-1644

CROMWELL’S STRATEGIC VISION 1643-1644 ‘He would not meddle against Newark…’ Cromwell’s strategic vision 1643-1644 MARTYN BENNETT* Nottingham Trent University, UK, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Cromwell with some justification is identified with East Anglia and this is often true of his early military career. However, his earliest campaigns were often focused on the area west of the Eastern Association counties and in particular they centred on the royalist garrison at Newark. This heavily defended town dominated several important communications arteries which Cromwell saw capturing the town as crucial to winning the war, at least in the region. Cromwell’s ruthless pursuit of his goal led him to criticize and even attack his superiors who did not see things his way. This article explores Cromwell’s developing strategic sense in the initial two years of the first civil war. Introduction The royalist garrison at Newark was not only one of the most substantial and successful garrisons in England during the civil wars: its steadfast loyalty had a devastating effect on the military careers of several parliamentarian generals and colonels. Between 1643 and 1645 Newark was responsible for, or played a role in, the severe mauling and even the termination of the careers of no less than five parliamentarian generals. The careers of two major generals in command of local forces, Sir Thomas Ballard and Sir John Meldrum, and three regional commanders, Thomas, Lord Grey of Groby, commander of the Midlands Association, Francis, Lord Willoughby of Parham, Lord Lieutenant of Lincolnshire and Edward Montague, Earl of Manchester, commander of the Eastern Association, all suffered because of it. -

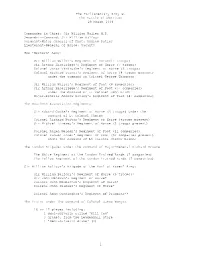

Sir William Waller MP Second-In-Command

The Parliamentary Army at The Battle of Cheriton 29 March 1644 Commander-in-Chief: Sir William Waller M.P. Second-in-Command: Sir William Balfour Sergeant-Major General of Foot: Andrew Potley Lieutenant-General of Horse: vacant? The 'Western' Army: Sir William Waller's Regiment of Horse(11 troops) Sir Arthur Haselrigge's Regiment of Horse (7 troops) Colonel Jonas Vandruske's Regiment of Horse (6 troops) Colonel Richard Turner's Regiment of Horse (4 troops present) under the command of Colonel George Thompson Sir William Waller's Regiment of Foot (8 companies) Sir Arthur Haselrigge's Regiment of Foot (5+ companies) under the command of Lt Colonel John Birch Major-General Andrew Potley's Regiment of Foot (4+ companies) The Southern Association Regiments: Sir Edward Cooke's Regiment of Horse (4 troops) under the command of Lt Colonel Thorpe Colonel Richard Norton's Regiment of Horse (troops present) Sir Michael Livesey's Regiment of Horse (5 troops present) Colonel Ralph Weldon's Regiment of Foot (11 companies) Colonel Samuel Jones' Regiment of Foot (6? companies present) under the command of Lt Colonel Jeremy Baines The London Brigade: under the command of Major-General Richard Browne The White Regiment of the London Trained Bands (7 companies) The Yellow Regiment of the London Trained Bands (7 companies) Sir William Balfour's Brigade of the Earl of Essex' Army: Sir William Balfour's Regiment of Horse (6 troops)* Sir John Meldrum's Regiment of Horse* Colonel John Middleton's Regiment of Horse* Coloenl John Dalbier's Regiment of Horse* Colonel Adam Cunningham's Regiment of Dragoons** The Train: under the command of Colonel James Wemyss 16 or 17 pieces including: 1 demi-culverin called 'Kill Cow' 3 drakes, from the Leadenhall Store 1 'demi-culverin drake' (?) 1 1 saker * These four regiments totalled 22 troops. -

The Blachford and Waterton Families of Dorset and Hampshire in the English Civil War

The Blachford and Waterton Families of Dorset and Hampshire in the English Civil War By Mark Wareham, August 2012 1 Introduction The English Civil war divided families as it divided the country and it set brother against brother and father against son. There are many examples of families at this time taking up arms against one another, like the Verneys and even the Cromwells. I too have discovered a divided family in my own ancestry and whilst many things have been written by other descendents and historians about the Blachfords and the Watertons during the civil war, I wanted to uncover the full story of their wartime experience and to discover what they actually did during this important conflict. Richard, son of Richard Blachford of Dorchester, married Eleanor Waterton in 1623 in Fordingbridge in Hampshire. Richard and Eleanor’s son was Robert Blachford who was born in 1624. These essays deal with three men; a grandson and two grandfathers who were divided by the civil war of 1642 to 1649. Two were royalists - Robert Waterton, born in 1565 and aged 77 at the outbreak of the war and his grandson Robert Blachford aged 18, and one was a roundhead – Richard Blachford, aged about 65-70. My family line from Richard and Robert Blachford and Eleanor, daughter of Robert Waterton, is shown in appendix two. Numbers in brackets and italics – see sources for reference. 2 Richard Blachford Richard Blachford was born in about 1570/5, probably at Exeter in Devon. He was a gentleman merchant, a clothier, who lived most of his life in Dorchester in Dorset. -

Nicholas Stoughton (1592–1648): MP, Surrey Militia Officer and Patron of International Learning

Nicholas Stoughton (1592–1648): MP, Surrey militia officer and patron of international learning In the seventeenth century many gentlemen’s sons left Oxford without a degree. On the surface they had nothing to show for their stay in the university.1 Surviving account books show that some of them spent their money on dancing and fencing lessons or on going boating, shooting or fishing, for which there were of course ample opportunities around the city.2 Others seem likely to have been more studious, but pinpointing what intellectual benefit they derived from their education is difficult. With the increasing digitisation of key sources, however, it is possible to spot evidence that could previously have gone unnoticed. Nicholas Stoughton of Stoke by Guildford, Surrey, matriculated at Oxford from New College as a scholar from Winchester on 22 March 1609, aged sixteen and a half.3 As was the custom, he was subsequently elected to a probationary fellowship. He departed some time before mid June 1613, when he was admitted to the Inner Temple and embarked on a career in the law.4 This was cut short when his elder brother died and he succeeded to the family estates. He then took his place in the public life of the county, becoming a justice of the peace (from 1624), a captain of militia horse (from 1626), a deputy lieutenant and, in 1637–8, sheriff. He also sat in Parliament for Guildford in 1624 and again between December 1645 and his death in March 1648, although he made relatively little impact on parliamentary records.5 In his public life he was remembered for his longstanding loyalty to his friend Sir Richard Onslow, a leading Surrey gentleman who galvanised support for moderate parliamentarianism in the county during the civil wars.