Valorizing Vernacular Architecture. Historical Keys for the Ongoing Discourse La Valorización De La Arquitectura Vernácula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Asbestos

The asbestos lie The past and present of an industrial catastrophe — Maria Roselli Maria Roselli, is an investigative journalist for asbestos issues, migration, and economic development. Born in Italy, raised and living in Zurich, Switzerland, Roselli has written frequently in German, Italian, and French media on asbestos use. Contributing authors: Laurent Vogel is researcher at the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI), which is based in Brussels, Belgium. ETUI is the independent research and training centre of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), which is the umbrella organisation of the European trade unions. Dr Barry Castleman, author of Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, now in its fifth edition, has frequently been called as an expert witness both for plaintiffs and defendants; he has also testified before the U.S. Congress on asbestos use in the United States. He lives in Garrett Park, Maryland. Laurie Kazan-Allen is the editor of the British Asbestos Newsletter and the Coordinator of the International Ban Asbestos Secretariat. She is based in London. Kathleen Ruff is the founder and coordinator of the organisation Right On Canada of the Rideau Institute to promote citizen action for advocating for human rights in Canadian government policies. In 2011, she was named Canadian Public Health Association’s National Public Health Hero for ‘revealing the inaccuracies in the propaganda that the asbestos industry has employed for the better part of the last century to mislead citizens about the seriousness of the threat of asbestos -

Architecture and Nation. the Schleswig Example, in Comparison to Other European Border Regions

In Situ Revue des patrimoines 38 | 2019 Architecture et patrimoine des frontières. Entre identités nationales et héritage partagé Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 DOI: 10.4000/insitu.21149 ISSN: 1630-7305 Publisher Ministère de la culture Electronic reference Peter Dragsbo, « Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions », In Situ [En ligne], 38 | 2019, mis en ligne le 11 mars 2019, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 ; DOI : 10.4000/insitu.21149 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. In Situ Revues des patrimoines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other Europe... 1 Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo 1 This contribution to the anthology is the result of a research work, carried out in 2013-14 as part of the research program at Museum Sønderjylland – Sønderborg Castle, the museum for Danish-German history in the Schleswig/ Slesvig border region. Inspired by long-term investigations into the cultural encounters and mixtures of the Danish-German border region, I wanted to widen the perspective and make a comparison between the application of architecture in a series of border regions, in which national affiliation, identity and power have shifted through history. The focus was mainly directed towards the old German border regions, whose nationality changed in the wave of World War I: Alsace (Elsaβ), Lorraine (Lothringen) and the western parts of Poland (former provinces of Posen and Westpreussen). -

D4.3 the Case of Historic Building

D4.3 WP4 Report describing the case of historic building Report describing the case of historic building | D4.3 4RinEU project | PAGE 2 Report describing the case of historic building | D4.3 Foreword Despite the low energy performances of the European building stock, the yearly renovation rate and the choice to perform a building deep renovation is strongly affected by uncertainties in terms of costs and benefits in the life cycle. The project 4RinEU faces these challenges, offering technology solutions and strategies to encourage the existing building stock transformation, fostering the use of renewable energies, and providing reliable business models to support a deep renovation. 4RinEU project minimizes failures in design and implementation, manages different stages of the deep renovation process - from the preliminary audit up to the end-of-life - and provides information on energy, comfort, users’ impact, and investment performance. The 4RinEU deep renovation strategy is based on 3 pillars: • technologies - driven by robustness - to decrease net primary energy use (60 to 70% compared to pre-renovation), allowing a reduction of life cycle costs over 30 years (15% compared to a typical renovation); • methodologies - driven by usability - to support the design and implementation of the technologies, encouraging all stakeholders’ involvement and ensuring the reduction of the renovation time; • business models - driven by reliability - to enhance the level of confidence of deep renovation investors, increasing the EU building stock transformation rate. 4RinEU technologies, tools and procedures are expected to generate significant impacts: energy savings, reduction of renovation time, improvement of occupants IEQ conditions, optimization of RES use, acceleration of EU residential building renovation rate. -

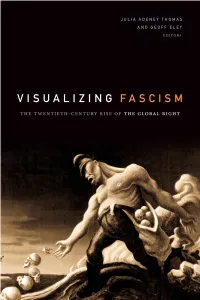

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

Vernacular Architecture; Definitions; Associations; France; Europe; Africa; Asia

Prepared and edited by Igor Sollogoub, intern at UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. Préparé et édité par Igor Sollogoub, stagiaire au Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS. © UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre, Mar. 2011 ISBN: 978-2-918086-09-3 ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and sites / Conseil International des Monuments et des Sites 49-51 rue de la Fédération 75015 Paris FRANCE http://www.international.icomos.org UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre / Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS : http://www.international.icomos.org/centre_documentation/index.html Cover photographs: Photos de couverture : Mali, Pays Dogon © IRD ; habitat troglodytique en Turquie © IRD ; Dordogne, France © Marie-Ange Mat ; Maison construite dans un banian au Vanuatu ©IRD 1 Index 1. Reference texts / Textes de référence 6 2. Generalities / Généralités 6 3. Africa / Afrique 9 Angola Benin Botswana Burkina Faso Cameroon / Cameroun Ethiopia / Ethiopie Ghana Kenya Madagascar Mali Mauritania / Mauritanie Niger Nigeria Senegal / Sénégal Seychelles South Africa / Afrique du Sud United Republic of Tanzania / Tanzanie Zambia / Zambie Zimbabwe 2 4. Latin America and the Carribean 21 Amérique latine et Caraïbes Argentina / Argentine Barbados / Barbade Belize Bolivia / Bolivie Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela / République bolivarienne du Vénézuela Brazil / Brésil Chile / Chili Colombia / Colombie Costa Rica Cuba Dominican Republic / République dominicaine Ecuador / Equateur El Salvador Guatemala Guyana / Guyane Haiti Jamaica -

1850 19505 2

Tourismusarchitektur Idegenforgalmi építészet Architettura per il turismo Tourism Architecture Arhitektura za turizam 1850 19505 2 Impressum Johann Schwertner Georg Kanhäuser Paolo Tomasella Ferenc Tóth Željko Trstenjak 5. Gemeinsamer Bericht über die Entwicklung von Tourismusarchitektur und -siedlungen im Alpen-Adria Raum von 1850 - 1950. 5. Közös jelentés az Alpok-Adria térség idegenforgalmi településeinek és építészetének fejlődéséről 1850 és 1950 között. 5. Rapporto comune sullo sviluppo dell’architettura e degli insediamenti turistici nella regione dell’Alpe Adria dal 1850 al 1950. 5. Joint report on the development of tourism architecture and settlements in the Alps-Adriatic region from 1850 - 1950. 5. zajedničko izvješće o razvoju arhitekture i naselja za turizam na prostoru Alpe – Jadran od 1850. do 1950. Regional Monograph part Co-authors Ilse Grascher, Carinthia Ria Mang, Styria Csaba Katona, Hungary Betty Bardi, Hungary Nina Hraba, Croatia Emiliana De Paulis, Friuli Venezia Giulia Publisher Alps-Adriatic-Alliance Project Group on Historical Centres Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria, 2020 Cover Design and Setting / Printing Friedrich Knapp, A-9300 St. Veit an der Glan Tel. 00 43 650 60 47 300 Number of Copies 300 ISBN 978-3-200-06856-8 © Alpen-Adria-Allianz / Alpok-Adria Szövetség / Alleanza Alpe-Adria / Alps-Adriatic-Alliance / Saveza Alpe-Jadran Projektgruppe Historische Zentren, Történelmi központok projektcsoport, Gruppo progetto Centri storici, Project Group on Historical Centres, Projektna skupina za povijesna središta 3 This book is dedicated to Arch. Prof. Dr. Gábor Winkler (1941–2015) Johann Schwertner Georg Kanhäuser Paolo Tomasella Ferenc Tóth Željko Trstenjak 5. Gemeinsamer Bericht über die Entwicklung von Tourismusarchitektur und -siedlungen im Alpen-Adria Raum von 1850–1950. -

Aesthetics of Building Material in the Buildings of Architect Augusts Malvess Jānis Krastiņš, Riga Technical University

Architecture and Urban Planning doi: 10.1515/aup-2017-0012 2017 / 13 Aesthetics of Building Material in the Buildings of Architect Augusts Malvess Jānis Krastiņš, Riga Technical University Abstract ‒ Architect Augusts Malvess is well-known in history of Latvian lysed in this article, particular attention being paid to means of architecture in general and in architecture education in Latvia in partic- artistic expression used in building architecture. ular, but so far not all of the buildings designed by him have been identi- fied and architecture of his creations has not been evaluated in the context of artistically stylistic and theoretical principles. The article presents the I. BUILDINGS BY A. MALVESS IN RIGA analyses of the architect’s specific creative approach based on the use of var- ious building materials with the purpose of achieving artistic expression. The most productive phase of A. Malves’s creative activity Several until now unknown, but significant facts in the history of Latvian coincided with the culmination of Art Nouveau. In 1909, when architecture have been explored. Malvess began to work independently, he designed the apart- Keywords ‒ 20th century architecture, A. Malvess, architectural ment houses at Stabu iela 99 (Figs. 1 and 2) and Katrīnas dam- stylistics. bis 20 (Fig. 3), and the following year, i.e. in 1910, the apart- ment houses with shops at Alūksnes iela 5 (Fig. 4) and Krišjāņa Valdemāra iela 18 (Fig. 5). Surfaces of rusticated travertine cre- INTRODUCTION ate artistic accents in the façades of all these buildings, and to make the contrast stronger, at Katrīnas dambis 20 and Alūksnes Architect Augusts Malvess (1878–1951) has made a signifi- iela 5 they are combined with bands of red brick.