Mapping the Religio-Political Landscape and Identity of Christian Emerging Adults Through a Reception Study of the Colbert Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology of Religion, Lundscow, Chapter 7, Cults

Sociology of Religion , Sociology 3440-090 Summer 2014, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office Room 429 Beh. Sci., Office Hours: Thursday - Friday, Noon – 4:00-pm Office Phone: (801) 531-3075 Home Phone: (801) 278-6413 Email: [email protected] I. Goals: The primary goal of this class is to give students a sociological understanding of religion as a powerful, important, and influential social institution that is associated with many social processes and phenomena that motivate and influence how people act and see the world around them. The class will rely on a variety of methods that include comparative analysis, theoretical explanations, ethnographic studies, and empirical studies designed to help students better understand religion and its impact upon societies, global-international events, and personal well-being. This overview of the nature, functioning, and diversity of religious institutions should help students make more discerning decisions regarding cultural, political, and moral issues that are often influenced by religion. II. Topics To Be Covered: The course is laid out in two parts. The first section begins with a review of conventional and theoretical conceptions of religion and an overview of the importance and centrality of religion to human societies. It emphasizes the diversity and nature of "religious experience" in terms of different denominations, cultures, classes, and individuals. This is followed by overview of sociological assumptions and theories and their application to religion. A variety of theoretical schools including, functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory, sociology of knowledge, sociobiology, feminist theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodern and critical theory will be addressed and applied to religion. -

The Liberty Champion, Volume 28 Issue 6)

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University 2010 -- 2011 Liberty University School Newspaper 10-12-2010 10-12-10 (The Liberty Champion, volume 28 issue 6) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/paper_10_11 Recommended Citation "10-12-10 (The Liberty Champion, volume 28 issue 6)" (2010). 2010 -- 2011. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/paper_10_11/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School Newspaper at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010 -- 2011 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAMPION is now online! Have we got a show s for you! www.LibertyChampion.com B1 liberty T uesday, O ctober 12, 2010 • V olume 2 8 Issue 5 Homecoming 2010 'Say Something' Domestic and Dating Violence Awareness Week challenges students. CINDI FAHLE [email protected] Two hundred red flags in DeMoss courtyard are serving as a reminder for students to “Say Something” as part of Domestic and Dating Vi olence Awareness Week’s Red Flag Campaign. The Student Government Association and the Office of Student Conduct banded together to spread the word on Liberty’s campus and pro mote the importance ofhealthy relationships. One of the goals of this co-curricular event is to help students learn to have healthy, respectful relationships with members of the opposite sex. Senior Conduct Officer Andrea Adams said. • See RED FLAG on A6 Negotiating to MARCHING MUSIC — The Liberty University Spirit of the Mountain Marching Band led the Homecoming parade Saturday. -

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

Oneorganism Ecosystem Discovered in African Gold Mine

3/19/14 One-Organism Ecosystem Discovered in African Gold Mine - Wired Science Science News for Your Neurons Share on Facebook 85 shares Tweet 7 0 Share 2 OneOrganism Ecosystem Discovered in African Gold Mine By Alexis Madrigal 10.09.08 11:19 AM Edit In the hot, dark water of a South African mine, scientists have found the world’s loneliest species. Everywhere else biologists have studied life on our planet, they’ve found communities of life, but today, biologists announced they have discovered an ecosystem that contains just a single species of bacteria. www.wired.com/wiredscience/2008/10/one-organism-ec/ 1/32 3/19/14 One-Organism Ecosystem Discovered in African Gold Mine - Wired Science In all other known ecosystems, the key functions of life — harvesting energy and elements like carbon and nitrogen from the environment — have been shared among different species. But in the water of the Mponeng gold mine, two miles under the earth’s surface, Desulforudis audaxviator carries out all of those functions by itself. In short, it’s the tidiest package of life found yet. "It is possible to pack everything necessary for maintaining life into one genome," said Dylan Chivian of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. All known life forms need carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and an energy source to live. Plants need nitrogen, but can’t just pull it from the atmosphere and start using it to make amino acids. Instead, they rely on archaea for that task. Interconnections like these form the basis of an ecosystem, often cheesily called the ‘web of life’. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

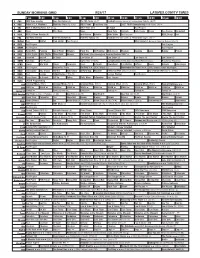

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

14. Swan Song

LISA K. PERDIGAO 14. SWAN SONG The Art of Letting Go in Glee In its five seasons, the storylines of Glee celebrate triumph over adversity. Characters combat what they perceive to be their limitations, discovering their voices and senses of self in New Directions. Tina Cohen-Chang overcomes her shyness, Kurt Hummel embraces his individuality and sexuality, Finn Hudson discovers that his talents extend beyond the football field, Rachel Berry finds commonality with a group instead of remaining a solo artist, Mike Chang is finally allowed to sing, and Artie Abrams is able to transcend his physical disabilities through his performances.1 But perhaps where Glee most explicitly represents the theme of triumph over adversity is in the series’ evasion of death. The threat of death appears in the series, oftentimes in the form of the all too real threats present in a high school setting: car accidents (texting while driving), school shootings, bullying, and suicide. As Artie is able to escape his wheelchair to dance in an elaborate sequence, if only in a dream, the characters are able to avoid the reality of death and part of the adolescent experience and maturation into adulthood. As Trites (2000) states, “For many adolescents, trying to understand death is as much of a rite of passage as experiencing sexuality is” (p. 117). However, Glee is forced to alter its plot in season five. The season begins with a real-life crisis for the series; actor Cory Monteith’s death is a devastating loss for the actors, writers, and producers as well as the series itself. -

The Rhetoric(S) of St. Augustine's Confessions

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Communication Scholarship Communication 2008 The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine's Confessions James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/comm_facpub Part of the Christianity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation James M. Farrell, "The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine's Confessions," Augustinian Studies 39:2 (2008), 265-291. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric(s) of St. Augustine’s Confessions. James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire Much of the scholarship on Augustine’s Confessions has consigned the discipline of rhetoric to the margins. Rhetoric was Augustine’s “major” in school, and his bread and bacon as a young adult. But in turning to God in the garden at Milan, Augustine also turned away from his profession. Rightly so, the accomplishment of Augustine’s conversion is viewed as a positive development. But the conversion story also structures the whole narrative of the Confessions and thus rhetoric is implicated in that narrative. It is the story of “Latin rhetorician turned Christian bishop.”1 Augustine’s intellectual and disciplinary evolution is mapped over a story of spiritual ascent. -

Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327186182 Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media Book · January 2018 CITATIONS READS 268 6,850 1 author: Tarleton Gillespie Microsoft 37 PUBLICATIONS 3,116 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Tarleton Gillespie on 20 December 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Custodians of the Internet platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media Tarleton Gillespie CUSTODIANS OF THE INTERNET CUSTODIANS OF THE INTERNET platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media tarleton gillespie Copyright © 2018 by Tarleton Gillespie. All rights reserved. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be repro- duced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. The Author has made this work available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License (CC BY- NC- SA 4.0) (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc- sa/4.0/). An online version of this work is available; it can be accessed through the author’s website at http://www.custodiansoftheinternet.org. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e- mail sales.press@yale. edu (U.S. offi ce) or [email protected] (U.K. -

South Park: (Des)Construção Iconoclasta Das Celebridades

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades São Paulo Agosto de 2012 2 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC-SP Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado São Paulo Agosto de 2012 3 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica ÉRICO FERNANDO DE OLIVEIRA South Park: (des)construção iconoclasta das celebridades Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica da PUC-SP Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado Comissão examinadora: __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ São Paulo Agosto de 2012 4 AGRADECIMENTOS À CAPES, pelo financiamento parcial da pesquisa. Ao Prof. Dr. José Luis Aidar Prado pela paciência e disponibilidade. Aos meus pais, irmãos e amigos, pela compreensão diante de minhas recusas. Aos meus colegas de curso, em especial, André Campos de Carvalho, Cynthia Menezes Mello e Fabíola Corbucci, Pela amizade e inestimável incentivo. Aos professores integrantes das bancas de qualificação e defesa, pelas orientações e disponibilidade. À Celina de Campos Horvat, por todos os motivos descritos acima. Toda piada é uma pequena revolução. (George Orwell) 5 Resumo O intuito desta pesquisa é estudar a construção social contemporânea das celebridades, bem como o papel que ela exerce na civilização midiática. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Juraj Štyrák When Jesters Do the Preaching Religious Parody and Satire in South Park Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Vanderziel, B.A. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ………………………………………… Author‟s signature I would like to thank my supervisor Jeffrey A. Vanderziel, B.A. for his wise guidance, valuable feedback, and nerves of steel. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. - 5 - 1. From Zeros to Heroes. History of “South Park” ...................................................... - 7 - 2. I don‟t get it! Theoretical Groundwork of Comedy ............................................... - 15 - 2.1. Parody ............................................................................................................. - 15 - 2.2. Incongruity ...................................................................................................... - 17 - 2.3. Satire ............................................................................................................... - 18 - 2.4. Intertextuality .................................................................................................. - 21 - 3. Laughing in the Face of God. Humor and Religion .............................................. - 26 - 4. Prophets,