DNA Replication Through Strand Displacement During Lagging Strand DNA Synthesis in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

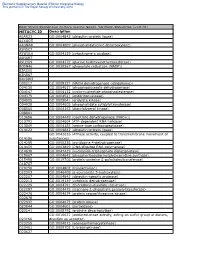

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Introduction of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase to Normal Human Fibroblasts Enhances DNA Repair Capacity

Vol. 10, 2551–2560, April 1, 2004 Clinical Cancer Research 2551 Introduction of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase to Normal Human Fibroblasts Enhances DNA Repair Capacity Ki-Hyuk Shin,1 Mo K. Kang,1 Erica Dicterow,1 INTRODUCTION Ayako Kameta,1 Marcel A. Baluda,1 and Telomerase, which consists of the catalytic protein subunit, No-Hee Park1,2 human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), the RNA component of telomerase (hTR), and several associated pro- 1School of Dentistry and 2Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Los Angeles, California teins, has been primarily associated with maintaining the integ- rity of cellular DNA telomeres in normal cells (1, 2). Telomer- ase activity is correlated with the expression of hTERT, but not ABSTRACT with that of hTR (3, 4). Purpose: From numerous reports on proteins involved The involvement of DNA repair proteins in telomere main- in DNA repair and telomere maintenance that physically tenance has been well documented (5–8). In eukaryotic cells, associate with human telomerase reverse transcriptase nonhomologous end-joining requires a DNA ligase and the (hTERT), we inferred that hTERT/telomerase might play a DNA-activated protein kinase, which is recruited to the DNA role in DNA repair. We investigated this possibility in nor- ends by the DNA-binding protein Ku. Ku binds to hTERT mal human oral fibroblasts (NHOF) with and without ec- without the need for telomeric DNA or hTR (9), binds the topic expression of hTERT/telomerase. telomere repeat-binding proteins TRF1 (10) and TRF2 (11), and Experimental Design: To study the effect of hTERT/ is thought to regulate the access of telomerase to telomere DNA telomerase on DNA repair, we examined the mutation fre- ends (12, 13). -

Curr.Opin.Chem. Biol., 15, 587-594

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Bacterial replicases and related polymerases Charles S McHenry Bacterial replicases are complex, tripartite replicative replication that are conserved among all life forms are machines. They contain a polymerase, Pol III, a b2 processivity illustrated in Figure 1. factor and a DnaX complex ATPase that loads b2 onto DNA and chaperones Pol III onto the newly loaded b2. Many Structure and function of a, the catalytic bacteria encode both a full length t and a shorter g form of subunit DnaX by a variety of mechanisms. The polymerase catalytic Like all polymerases, Pol III a contains palm, thumb and subunit of Pol III, a, contains a PHP domain that not only binds fingers domains, in the shape of a cupped right hand 2+ to prototypical e Mg -dependent exonuclease, but also Figure 2. However, apo-enzyme structures of the full 2+ contains a second Zn -dependent proofreading length Thermus aquaticus (Taq) and a truncated version of exonuclease, at least in some bacteria. Replication of the E. coli (Eco) a subunit revealed a big surprise: the palm chromosomes of low GC Gram-positive bacteria require two domain has the basic fold of the X family of DNA Pol IIIs, one of which, DnaE, appears to extend RNA primers a polymerases, which includes the slow, non-processive only short distance before handing the product off to the major Pol bs [1 ,2 ]. replicase, PolC. Other bacteria encode a second Pol III (ImuC) that apparently replaces Pol V, required for induced A ternary complex of a dideoxy-terminated primer-tem- mutagenesis in E. -

Large XPF-Dependent Deletions Following Misrepair of a DNA Double Strand Break Are Prevented by the RNA:DNA Helicase Senataxin

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Large XPF-dependent deletions following misrepair of a DNA double strand break are prevented Received: 26 October 2017 Accepted: 9 February 2018 by the RNA:DNA helicase Published: xx xx xxxx Senataxin Julien Brustel1, Zuzanna Kozik1, Natalia Gromak2, Velibor Savic3,4 & Steve M. M. Sweet1,5 Deletions and chromosome re-arrangements are common features of cancer cells. We have established a new two-component system reporting on epigenetic silencing or deletion of an actively transcribed gene adjacent to a double-strand break (DSB). Unexpectedly, we fnd that a targeted DSB results in a minority (<10%) misrepair event of kilobase deletions encompassing the DSB site and transcribed gene. Deletions are reduced upon RNaseH1 over-expression and increased after knockdown of the DNA:RNA helicase Senataxin, implicating a role for DNA:RNA hybrids. We further demonstrate that the majority of these large deletions are dependent on the 3′ fap endonuclease XPF. DNA:RNA hybrids were detected by DNA:RNA immunoprecipitation in our system after DSB generation. These hybrids were reduced by RNaseH1 over-expression and increased by Senataxin knock-down, consistent with a role in deletions. Overall, these data are consistent with DNA:RNA hybrid generation at the site of a DSB, mis-processing of which results in genome instability in the form of large deletions. DNA is the target of numerous genotoxic attacks that result in diferent types of damage. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur at low frequency, compared with single-strand breaks and other forms of DNA damage1, however DSBs pose the risk of translocations and deletions and their repair is therefore essential to cell integrity. -

Phosphate Steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 Promotes 50-flap Specificity and Incision to Prevent Genome Instability

ARTICLE Received 18 Jan 2017 | Accepted 5 May 2017 | Published 27 Jun 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15855 OPEN Phosphate steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 promotes 50-flap specificity and incision to prevent genome instability Susan E. Tsutakawa1,*, Mark J. Thompson2,*, Andrew S. Arvai3,*, Alexander J. Neil4,*, Steven J. Shaw2, Sana I. Algasaier2, Jane C. Kim4, L. David Finger2, Emma Jardine2, Victoria J.B. Gotham2, Altaf H. Sarker5, Mai Z. Her1, Fahad Rashid6, Samir M. Hamdan6, Sergei M. Mirkin4, Jane A. Grasby2 & John A. Tainer1,7 DNA replication and repair enzyme Flap Endonuclease 1 (FEN1) is vital for genome integrity, and FEN1 mutations arise in multiple cancers. FEN1 precisely cleaves single-stranded (ss) 50-flaps one nucleotide into duplex (ds) DNA. Yet, how FEN1 selects for but does not incise the ss 50-flap was enigmatic. Here we combine crystallographic, biochemical and genetic analyses to show that two dsDNA binding sites set the 50polarity and to reveal unexpected control of the DNA phosphodiester backbone by electrostatic interactions. Via ‘phosphate steering’, basic residues energetically steer an inverted ss 50-flap through a gateway over FEN1’s active site and shift dsDNA for catalysis. Mutations of these residues cause an 18,000-fold reduction in catalytic rate in vitro and large-scale trinucleotide (GAA)n repeat expansions in vivo, implying failed phosphate-steering promotes an unanticipated lagging-strand template-switch mechanism during replication. Thus, phosphate steering is an unappreciated FEN1 function that enforces 50-flap specificity and catalysis, preventing genomic instability. 1 Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, USA. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Redundancy in Ribonucleotide Excision Repair: Competition, Compensation, and Cooperation

DNA Repair 29 (2015) 74–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect DNA Repair j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dnarepair Redundancy in ribonucleotide excision repair: Competition, compensation, and cooperation ∗ Alexandra Vaisman, Roger Woodgate Laboratory of Genomic Integrity, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-3371, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The survival of all living organisms is determined by their ability to reproduce, which in turn depends Received 1 November 2014 on accurate duplication of chromosomal DNA. In order to ensure the integrity of genome duplication, Received in revised form 7 February 2015 DNA polymerases are equipped with stringent mechanisms by which they select and insert correctly Accepted 9 February 2015 paired nucleotides with a deoxyribose sugar ring. However, this process is never 100% accurate. To fix Available online 16 February 2015 occasional mistakes, cells have evolved highly sophisticated and often redundant mechanisms. A good example is mismatch repair (MMR), which corrects the majority of mispaired bases and which has been Keywords: extensively studied for many years. On the contrary, pathways leading to the replacement of nucleotides Ribonucleotide excision repair with an incorrect sugar that is embedded in chromosomal DNA have only recently attracted significant Nucleotide excision repair attention. This review describes progress made during the last few years in understanding such path- Mismatch repair Ribonuclease H ways in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Genetic studies in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Flap endonuclease demonstrated that MMR has the capacity to replace errant ribonucleotides, but only when the base is DNA polymerase I mispaired. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Figure S1. The functionality of the tagged Arp6 and Swr1 was confirmed by monitoring cell growth and sensitivity to hydeoxyurea (HU). Five-fold serial dilutions of each strain were plated on YPD with or without 50 mM HU and incubated at 30°C or 37°C for 3 days. Figure S2. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 3. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 3L, Tel 3R, CEN3, and the RP gene are shown under the panels. Figure S3. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) in the whole chromosome region are compared. The position of Tel 4L, Tel 4R, CEN4, SWR1, and RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S4. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on the region including the SWR1 gene of chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6- FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position and orientation of the SWR1 gene is shown. Figure S5. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 5. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 5L, Tel 5R, CEN5, and the RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S6. Preferential localization of Arp6 and Swr1 in the 5′ end of genes. Vertical bars represent the binding ratio of proteins in each locus. -

Potent Inhibition of Human Telomerase by U-73122

Journal of Biomedical Science (2006) 13:667–674 667 DOI 10.1007/s11373-006-9100-z Potent inhibition of human telomerase by U-73122 Yi-Jui Chen, Wei-Yun Sheng, Pei-Rong Huang & Tzu-Chien V. Wang* Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Chang Gung University, Kwei-San, Tao-Yuan, 333, Taiwan Received 28 April 2006; accepted 14 June 2006 Ó 2006 National Science Council, Taipei Key words: alkylating agents, cancer therapyzU-73122, N-ethylmaleimide, telomerase inhibitor Summary Telomerase activity is repressed in normal human somatic cells, but is activated in most cancers, suggesting that telomerase may be an important target for cancer therapy. In this study, we report that U-73122, an amphiphilic alkylating agent that is commonly used as an inhibitor for phospholipase C, is also a potent and selective inhibitor of human telomerase. The inhibition of telomerase by U-73122 was attributed primarily to the pyrrole-2,5-dione group, since its structural analog U-73343 did not inhibit telomerase. In confirmation, we observed that telomerase was inhibited by N-ethylmaleimide, but not N-ethylsuccinimide. The IC50 value of U-73122 for the in vitro inhibition of telomerase activity is 0.2 lM, which is comparable to or slightly more sensitive than that for phospholipase C. The inhibitory action of U-73122 on telomerase appears to be rather selective since the presence of externally added proteins did not protect the inhibition and the IC50 values for the other enzymes tested in this study were at least an order of magnitude higher than that for telomerase. Furthermore, we demonstrate that U-73122 can inhibit telomerase in hemato- poietic cancer cells. -

M1224-100 Thermostable Rnase H

BioVision 03/17 For research use only Thermostable RNAse H CATALOG NO.: M1224-100 10X THERMOSTABLE RNAse H REACTION BUFFER: 500 mM Tris-HCl, 1000 mM NaCl, AMOUNT: 500 U (100 µl) 100 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5 PRODUCT SOURCE: Recombinant E. coli REACTION CONDITIONS: Use 1X Thermostable RNAse H Reaction Buffer and incubate CONCENTRATION: 100 U/µl at a chosen temperature between 65°C and 95°C (enzyme half-life is 2 hours at 70°C and 30 minutes at 95°C). FORM: Liquid. Enzyme supplied with 10X Reaction Buffer COMPONENTS: Product Name Size Part. No. Thermostable RNAse H (5 U/μl) 100 µl M1224-100-1 10X Thermostable RNAse Reaction Buffer 500 µl M1224-100-2 DESCRIPTION: Thermostable RNAse H (Ribonuclease H) is an endoribonuclease that specifically hydrolyzes the phosphodiester bonds of RNA strands in RNA-DNA hybrids. Unlike E. coli RNAse H which is inactivated at temperatures above 55°C, Thermostable RNase H can withstand much higher temperatures. These higher temperatures allow for higher hybridization stringency for RNA-DNA heteroduplexes resulting in more specific hydrolysis of RNA. Thermostable RNase H has optimal activity above 65°C and is active up to 95°C making it useful for a broad range of applications. APPLICATIONS: 1. High-stringency hybrid selection and mapping of mRNA structure 2. Removal of mRNA prior to synthesis of second strand cDNA 3. Removal of the poly(A) sequences from mRNA in the presence of oligo (dT) 4. Directed cleavage of RNA RELATED PRODUCTS: STORAGE CONDITIONS: Store at -20°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of all E. -

Supp Material.Pdf

Simon et al. Supplementary information: Table of contents p.1 Supplementary material and methods p.2-4 • PoIy(I)-poly(C) Treatment • Flow Cytometry and Immunohistochemistry • Western Blotting • Quantitative RT-PCR • Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization • RNA-Seq • Exome capture • Sequencing Supplementary Figures and Tables Suppl. items Description pages Figure 1 Inactivation of Ezh2 affects normal thymocyte development 5 Figure 2 Ezh2 mouse leukemias express cell surface T cell receptor 6 Figure 3 Expression of EZH2 and Hox genes in T-ALL 7 Figure 4 Additional mutation et deletion of chromatin modifiers in T-ALL 8 Figure 5 PRC2 expression and activity in human lymphoproliferative disease 9 Figure 6 PRC2 regulatory network (String analysis) 10 Table 1 Primers and probes for detection of PRC2 genes 11 Table 2 Patient and T-ALL characteristics 12 Table 3 Statistics of RNA and DNA sequencing 13 Table 4 Mutations found in human T-ALLs (see Fig. 3D and Suppl. Fig. 4) 14 Table 5 SNP populations in analyzed human T-ALL samples 15 Table 6 List of altered genes in T-ALL for DAVID analysis 20 Table 7 List of David functional clusters 31 Table 8 List of acquired SNP tested in normal non leukemic DNA 32 1 Simon et al. Supplementary Material and Methods PoIy(I)-poly(C) Treatment. pIpC (GE Healthcare Lifesciences) was dissolved in endotoxin-free D-PBS (Gibco) at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. Mice received four consecutive injections of 150 μg pIpC every other day. The day of the last pIpC injection was designated as day 0 of experiment. -

Arthur Kornberg Discovered (The First) DNA Polymerase Four

Arthur Kornberg discovered (the first) DNA polymerase Using an “in vitro” system for DNA polymerase activity: 1. Grow E. coli 2. Break open cells 3. Prepare soluble extract 4. Fractionate extract to resolve different proteins from each other; repeat; repeat 5. Search for DNA polymerase activity using an biochemical assay: incorporate radioactive building blocks into DNA chains Four requirements of DNA-templated (DNA-dependent) DNA polymerases • single-stranded template • deoxyribonucleotides with 5’ triphosphate (dNTPs) • magnesium ions • annealed primer with 3’ OH Synthesis ONLY occurs in the 5’-3’ direction Fig 4-1 E. coli DNA polymerase I 5’-3’ polymerase activity Primer has a 3’-OH Incoming dNTP has a 5’ triphosphate Pyrophosphate (PP) is lost when dNMP adds to the chain E. coli DNA polymerase I: 3 separable enzyme activities in 3 protein domains 5’-3’ polymerase + 3’-5’ exonuclease = Klenow fragment N C 5’-3’ exonuclease Fig 4-3 E. coli DNA polymerase I 3’-5’ exonuclease Opposite polarity compared to polymerase: polymerase activity must stop to allow 3’-5’ exonuclease activity No dNTP can be re-made in reversed 3’-5’ direction: dNMP released by hydrolysis of phosphodiester backboneFig 4-4 Proof-reading (editing) of misincorporated 3’ dNMP by the 3’-5’ exonuclease Fidelity is accuracy of template-cognate dNTP selection. It depends on the polymerase active site structure and the balance of competing polymerase and exonuclease activities. A mismatch disfavors extension and favors the exonuclease.Fig 4-5 Superimposed structure of the Klenow fragment of DNA pol I with two different DNAs “Fingers” “Thumb” “Palm” red/orange helix: 3’ in red is elongating blue/cyan helix: 3’ in blue is getting edited Fig 4-6 E.