Notes on the Reproduction of the Oceanic Whitetip Shark, Carcharhinus Longimanus, in the Southwestern Equatorial Atlantic Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11 the Biology and Ecology of the Oceanic Whitetip Shark, Carcharhinus Longimanus

Chapter 11 The Biology and Ecology of the Oceanic Whitetip Shark, Carcharhinus longimanus Ramón Bonfi l, Shelley Clarke and Hideki Nakano Abstract The oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) is a common circumtropical preda- tor and is taken as bycatch in many oceanic fi sheries. This summary of its life history, dis- tribution and abundance, and fi shery-related information is supplemented with unpublished data taken during Japanese tuna research operations in the Pacifi c Ocean. Oceanic whitetips are moderately slow-growing sharks that do not appear to have differential growth rates by sex, and individuals in the Atlantic and Pacifi c Oceans seem to grow at similar rates. They reach sexual maturity at approximately 170–200 cm total length (TL), or 4–7 years of age, and have a 9- to 12-month embryonic development period. Pupping and nursery areas are thought to exist in the central Pacifi c, between 0ºN and 15ºN. According to two demographic metrics, the resilience of C. longimanus to fi shery exploitation is similar to that of blue and shortfi n mako sharks. Nevertheless, reported oceanic whitetip shark catches in several major longline fi sheries represent only a small fraction of total shark catches, and studies in the Northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico suggest that this species has suffered signifi cant declines in abundance. Stock assessment has been severely hampered by the lack of species-specifi c catch data in most fi sheries, but recent implementation of species-based reporting by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) and some of its member countries will provide better data for quantitative assessment. -

Sharks in Crisis: a Call to Action for the Mediterranean

REPORT 2019 SHARKS IN CRISIS: A CALL TO ACTION FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN WWF Sharks in the Mediterranean 2019 | 1 fp SECTION 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Written and edited by WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative / Evan Jeffries (www.swim2birds.co.uk), based on data contained in: Bartolí, A., Polti, S., Niedermüller, S.K. & García, R. 2018. Sharks in the Mediterranean: A review of the literature on the current state of scientific knowledge, conservation measures and management policies and instruments. Design by Catherine Perry (www.swim2birds.co.uk) Front cover photo: Blue shark (Prionace glauca) © Joost van Uffelen / WWF References and sources are available online at www.wwfmmi.org Published in July 2019 by WWF – World Wide Fund For Nature Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative as the copyright owner. © Text 2019 WWF. All rights reserved. Our thanks go to the following people for their invaluable comments and contributions to this report: Fabrizio Serena, Monica Barone, Adi Barash (M.E.C.O.), Ioannis Giovos (iSea), Pamela Mason (SharkLab Malta), Ali Hood (Sharktrust), Matthieu Lapinksi (AILERONS association), Sandrine Polti, Alex Bartoli, Raul Garcia, Alessandro Buzzi, Giulia Prato, Jose Luis Garcia Varas, Ayse Oruc, Danijel Kanski, Antigoni Foutsi, Théa Jacob, Sofiane Mahjoub, Sarah Fagnani, Heike Zidowitz, Philipp Kanstinger, Andy Cornish and Marco Costantini. Special acknowledgements go to WWF-Spain for funding this report. KEY CONTACTS Giuseppe Di Carlo Director WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative Email: [email protected] Simone Niedermueller Mediterranean Shark expert Email: [email protected] Stefania Campogianni Communications manager WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative Email: [email protected] WWF is one of the world’s largest and most respected independent conservation organizations, with more than 5 million supporters and a global network active in over 100 countries. -

Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay to Detect Illegal Trade of CITES-Listed

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Multiplex real-time PCR assay to detect illegal trade of CITES-listed shark species Received: 29 March 2018 Diego Cardeñosa 1,2, Jessica Quinlan3, Kwok Ho Shea4 & Demian D. Chapman3 Accepted: 23 October 2018 The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is a Published: xx xx xxxx multilateral environmental agreement to ensure that the international trade of threatened species is either prohibited (Appendix I listed species) or being conducted legally, sustainably, and transparently (Appendix II listed species). Twelve threatened shark species exploited for their fns, meat, and other products have been listed under CITES Appendix II. Sharks are often traded in high volumes, some of their products are visually indistinguishable, and most importing/exporting nations have limited capacity to detect illicit trade and enforce the regulations. High volume shipments often must be screened after only a short period of detainment (e.g., a maximum of 24 hours), which together with costs and capacity issues have limited the use of DNA approaches to identify illicit trade. Here, we present a reliable, feld-based, fast (<4 hours), and cost efective ($0.94 USD per sample) multiplex real- time PCR protocol capable of detecting nine of the twelve sharks listed under CITES in a single reaction. This approach facilitates detection of illicit trade, with positive results providing probable cause to detain shipments for more robust forensic analysis. We also provide evidence of its application in real law enforcement scenarios in Hong Kong. Adoption of this approach can help parties meet their CITES requirements, avoiding potential international trade sanctions in the future. -

1 a Petition to List the Oceanic Whitetip Shark

A Petition to List the Oceanic Whitetip Shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) as an Endangered, or Alternatively as a Threatened, Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act and for the Concurrent Designation of Critical Habitat Oceanic whitetip shark (used with permission from Andy Murch/Elasmodiver.com). Submitted to the U.S. Secretary of Commerce acting through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Marine Fisheries Service September 21, 2015 By: Defenders of Wildlife1 535 16th Street, Suite 310 Denver, CO 80202 Phone: (720) 943-0471 (720) 942-0457 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Defenders of Wildlife would like to thank Courtney McVean, a law student at the University of Denver, Sturm college of Law, for her substantial research and work preparing this Petition. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 4 II. GOVERNING PROVISIONS OF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT ............................................. 5 A. Species and Distinct Population Segments ....................................................................... 5 B. Significant Portion of the Species’ Range ......................................................................... 6 C. Listing Factors ....................................................................................................................... 7 D. 90-Day and 12-Month Findings ........................................................................................ -

This Process Wherein 2 Organisms Help One Another Is Often Called Symbiosis Or Mutualism

This process wherein 2 organisms help one another is often called symbiosis or mutualism. The terms are often used interchangeably. Technically, mutualism is an ecological interaction between at least two species (=partners) where both partners benefit from the relationship. Symbiosis on the other hand is defined as an ecological interaction between at least two species (=partners) where there is persistent contact between the partners. Coral is an extremely important habitat. Coral is an animal which has a dinoflagellate living in it called Zooxanthellae You can see where the Zooxanthellae live in the coral and these provide oxygen to the coral which provides protection to the Zooxanthellae If the coral is stressed, the Zooxanthellae leave the coral and the coral becomes “bleached” and may die if the Zooxanthellae do not return. Fish have evolved so that the coral provides them with a kind of “background” against which they become harder for predators to see them WORMS Several different phyla Nematodes, Platyhelminthes, annelids etc) . Some people do eat worms but several kinds are parasitic and there are dangers in doing this. Many marine animals will eat worms. ECHINODERMS Some examples: Star fish, sea cucumbers, crinoids Possible to eat, but not much meat! More likely eaten by other animals. Interesting regenerative powers. ARTHROPODS (joint legged animals) Some examples: Crabs, lobsters and so on. Some are edible. Insects are arthropods and many people in the world eat them. Horseshoe crabs, are here too but are more closely related to the spiders than to the crabs proper. Lobster crab Barnacles Horseshoe crab MOLLUSKS Examples: Clams, mussels , snails Clams and other mollusks are regularly eaten around the world. -

Oceanic Whitetip Shark Fact Sheet

OCEANIC WHITETIP SHARK Carcharhinus longimanus Proposed by Brazil, Colombia and the United States. Inclusion of Carcharhinus longimanus in Appendix II in accordance with Article II paragraph 2(a) of the Convention and satisfying Criterion A in Annex 2a of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15). Inclusion in Appendix II with the following annotation: “The entry into effect of the inclusion of Carcharhinus longimanus in Appendix II will be delayed by 18 months to enable Parties to resolve the related technical and administrative issues.” RECOMMENDATION : SUPPORT The oceanic whitetip shark was once one of the most widely distributed and abundant shark species in all tropical and subtropical oceans from 42ºN to 35ºS, usually found far offshore or in areas with narrow continental shelves1. One of the most slow-growing sharks, the oceanic whitetip also has small litters2. The species has suffered drastic declines. Populations of oceanic whitetip sharks have declined by >99% in the Gulf of Mexico3, 60% to 70% in the northwest and central Atlantic Ocean4,5. And up to a 10-fold decline in abundance from the baseline in the central Pacific Ocean6. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the species as Vulnerable globally on their Red List of Threatened Species, and has assessed the species as Critically Endangered in the Northwest and Western Central Atlantic7. THREATS TO OCEANIC WHITETIP SHARKS The threats to the species are bycatch in pelagic longline and drift net fisheries for swordfish and tuna, and the unsustainable harvest for the international fin trade8. There is evidence that international trade is driving retention of bycatch9. -

![Blue Shark [E] BLUE SHARK](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8084/blue-shark-e-blue-shark-1168084.webp)

Blue Shark [E] BLUE SHARK

Blue shark [E] BLUE SHARK SUPPORTING INFORMATION (Information collated from reports of the Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch and other sources as cited) CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT MEASURES Blue shark in the Indian Ocean are currently subject to a number of Conservation and Management Measures adopted by the Commission: Resolution 15/01 On the recording of catch and effort data by fishing vessels in the IOTC area of competence sets out the minimum logbook requirements for purse seine, longline, gillnet, pole and line, handline and trolling fishing vessels over 24 metres length overall and those under 24 metres if they fish outside the EEZs of their flag States within the IOTC area of competence. As per this Resolution, catch of all sharks must be recorded (retained and discarded). Resolution 15/02 Mandatory statistical reporting requirements for IOTC Contracting Parties and Cooperating Non-Contracting Parties (CPCs) indicated that the provisions, applicable to tuna and tuna-like species, are applicable to shark species.Resolution 11/04 On a Regional Observer Scheme requires data on blue shark interactions to be recorded by observers and reported to the IOTC within 150 days. The Regional Observer Scheme (ROS) started on 1st July 2010. Resolution 17/05 On the conservation of sharks caught in association with fisheries managed by IOTC includes minimum reporting requirements for sharks, calls for full utilisation of sharks and includes a ratio of fin-to-body weight for frozen shark fins retained onboard a vessel and a prohibition on the removal of fins for sharks landed fresh. Extracts from Resolutions 15/01,15/02, 11/04 and 05/05 RESOLUTION 15/01 ON THE RECORDING OF CATCH AND EFFORT DATA BY FISHING VESSELS IN THE IOTC AREA OF COMPETENCE Para. -

First Age and Growth Estimates in the Deep Water Shark, Etmopterus Spinax (Linnaeus, 1758), by Deep Coned Vertebral Analysis

Mar Biol DOI 10.1007/s00227-007-0769-y RESEARCH ARTICLE First age and growth estimates in the deep water shark, Etmopterus Spinax (Linnaeus, 1758), by deep coned vertebral analysis Enrico Gennari · Umberto Scacco Received: 2 May 2007 / Accepted: 4 July 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract The velvet belly Etmopterus spinax (Linnaeus, by an alternation of translucent and opaque areas (Ride- 1758) is a deep water bottom-dwelling species very com- wood 1921; Urist 1961; Cailliet et al. 1983). Vertebral mon in the western Mediterranean sea. This species is a dimensions, as well as their degree of calciWcation, vary portion of the by-catch of the red shrimps and Norway lob- considerably within the elasmobranch group (La Marca sters otter trawl Wsheries on the meso and ipo-bathyal 1966; Applegate 1967; Moss 1977). For example, vertebrae grounds. A new, simple, rapid, and inexpensive vertebral of coastal and pelagic species are more calciWed than those preparation method was used on a total of 241 specimens, of bottom dwelling deep-water sharks (Cailliet et al. 1986; sampled throughout 2000. Post-cranial portions of vertebral Cailliet 1990). These diVerences are also reXected in varia- column were removed and vertebrae were prepared for age- tions of shape and in growth zone appearance, such as the ing readings. Band pair counts ranged from 0 to 9 in presence and quality of bands and/or rings. Due to these females, and from 0 to 7 in males. Von BertalanVy growth diVerences, a general protocol for the elasmobranch group equations estimated for both sexes suggested a higher is not really available because of the high variability of cal- W longevity for females (males: L1 = 394.3 mm k =0.19 ci cation degree among species (Applegate 1967; Cailliet W t0 = ¡1.41 L0 = 92.7 mm A99 = 18.24 years; females: L1 = et al. -

Species Composition of the Largest Shark Fin Retail-Market in Mainland

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Species composition of the largest shark fn retail‑market in mainland China Diego Cardeñosa1,2*, Andrew T. Fields1, Elizabeth A. Babcock3, Stanley K. H. Shea4, Kevin A. Feldheim5 & Demian D. Chapman6 Species‑specifc monitoring through large shark fn market surveys has been a valuable data source to estimate global catches and international shark fn trade dynamics. Hong Kong and Guangzhou, mainland China, are the largest shark fn markets and consumption centers in the world. We used molecular identifcation protocols on randomly collected processed fn trimmings (n = 2000) and non‑ parametric species estimators to investigate the species composition of the Guangzhou retail market and compare the species diversity between the Guangzhou and Hong Kong shark fn retail markets. Species diversity was similar between both trade hubs with a small subset of species dominating the composition. The blue shark (Prionace glauca) was the most common species overall followed by the CITES‑listed silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini), smooth hammerhead shark (S. zygaena) and shortfn mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). Our results support previous indications of high connectivity between the shark fn markets of Hong Kong and mainland China and suggest that systematic studies of other fn trade hubs within Mainland China and stronger law‑enforcement protocols and capacity building are needed. Many shark populations have declined in the last four decades, mainly due to overexploitation to supply the demand for their fns in Asia and meat in many other countries 1–4. Mainland China was historically the world’s second largest importer of shark fns and foremost consumer of shark fn soup, yet very little is known about the species composition of shark fns in this trade hub2. -

Color and Learn: Sharks of Massachusetts!

COLOR AND LEARN: SHARKS OF MASSACHUSETTS! This book belongs to: WHAT IS A SHARK? Sharks are fish that have vertebrae (skeletons) made ofcartilage instead of bones. Sharks come in all different shapes, sizes, and colors. Sharks have different kinds of teeth, feeding patterns, swimming styles, and behaviors that help them to survive in all different kinds of aquatic habitats! Can you label the different parts of a shark? second dorsal fin caudal (tail) fin pelvic fin gills anal fin pectoral fin nostril mouth eye Dorsal fin There are around 500 species of sharks in the world. Massachusetts coastal waters provide ideal habitat for several kinds of Atlantic Ocean sharks that visit our waters each season! Massachusetts HOW LONG HAVE SHARKS BEEN ON EARTH? Sharks have been on Earth since before the dinosaurs! Scientists learn about early sharks by studying fossils. Shark fossils can tell us a lot about what food the shark ate, what their habitat looked like, and how they are related to other sharks. The ancient sharks on this page are extinct. Acanthodes (ah-can-tho-deez), or “spiny shark,” was the first fish to have a cartilage skeleton! Cladoselache (clay-do-sel-ah-kee) had a body and tail shaped for swimming fast. It did not have the same kind of skin that we see in modern sharks today. Stethacanthus (stef-ah-can-thus), or “anvil shark”, had a dorsal fin shaped like an ironing board! 450 370 360 200 145 60 6.5 MILLIONS OF YEARS AGO DINOSAURS EVOLVE WHAT ARE “MODERN” SHARKS? “Modern” sharks are species that have body parts (both inside and out!) that can be found on sharks living today. -

Closing the Loopholes on Shark Finning

Threatened European sharks Like many animals before them, sharks have become prey to human indulgence. Today, sharks are among the ocean’s most threatened species. PORBEAGLE SHARK (Lamna nasus) BASKING SHARK (Cetorhinus maximus) COMMON THRESHER SHARK Similar to killing elephants for their valuable tusks, Critically Endangered off Europe Vulnerable globally (Alopias vulpinus) sharks are now often hunted for a very specific part of Closing Vulnerable globally their bodies – their fins. Fetching up to 500 Euros a kilo when dried, shark fins the SMOOTH HAMMERHEAD (Sphyrna zygaena) SPINY DOGFISH (Squalus acanthias) TOPE SHARK (Galeorhinus galeus) are rich pickings for fishermen. Most shark fins end up Endangered globally Critically Endangered off Europe Vulnerable globally in Asia where shark fin soup is a traditional delicacy and status symbol. loopholes With shark fins fetching such a high price, and with the rest of the shark being so much less valuable, many fishermen have taken to ‘finning’ the sharks they catch SHORTFIN MAKO (Isurus oxyrinchus) COMMON GUITARFISH (Rhinobatos rhinobatos) BLUE SHARK (Prionace glauca) Vulnerable globally Proposed endangered in Mediterranean Near Threatened globally to save room on their boats for the bodies of more on commercially important fish. shark GREAT WHITE SHARK (Carcharadon carcharias) COMMON SAWFISH (Pristis pristis) ANGEL SHARK (Squatina squatina) Vulnerable globally Assumed Extinct off Europe Critically Endangered off Europe finning Globally Threatened sharks on the IUCN (International Union -

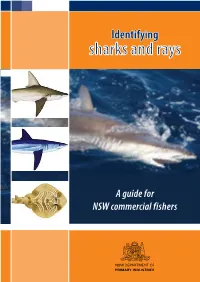

Identifying Sharks and Rays

NSW DPI Identifying sharks and rays A guide for NSW commercial fishers Important If a shark or ray cannot be confidently identified using this guide, it is recommended that either digital images are obtained or the specimen is preserved. Please contact NSW DPI research staff for assistance: phone 1300 550 474 or email [email protected] Contents Introduction 4 How to use this guide 5 Glossary 6-7 Key 1 Whaler sharks and other sharks of similar appearance 8-9 to whalers – upper precaudal pit present Key 2 Sharks of similar appearance to whaler sharks – no 10 precaudal pit Key 3 Mackerel (great white and mako), hammerhead and 11 thresher sharks Key 4 Wobbegongs and some other patterned 12 bottom-dwelling sharks Key 5 Sawsharks and other long-snouted sharks and rays 13 2 Sandbar shark 14 Great white shark 42 Bignose shark 15 Porbeagle 43 Dusky whaler 16 Shortfin mako 44 Silky shark 17 Longfin mako 45 Oceanic whitetip shark 18 Thresher shark 46 Tiger shark 19 Pelagic thresher 47 Common blacktip shark 20 Bigeye thresher 48 Spinner shark 21 Great hammerhead 49 Blue shark 22 Scalloped hammerhead 50 Sliteye shark 23 Smooth hammerhead 51 Bull shark 24 Eastern angelshark 52 Bronze whaler 25 Australian angelshark 53 Weasel shark 26 Banded wobbegong 54 Lemon shark 27 Ornate wobbegong 55 Grey nurse shark 28 Spotted wobbegong 56 Sandtiger (Herbst’s nurse) shark 29 Draughtboard shark 57 Bluntnose sixgill shark 30 Saddled swellshark 58 Bigeye sixgill shark 31 Whitefin swellshark 59 Broadnose shark 32 Port Jackson shark 60 Sharpnose sevengill