Alternatives to Growth-Centric Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Fiscal Decentralization in Buddhist Economics: An

4. FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN BUDDHIST ECONOMICS: AN INTERACTIVE ANALYSIS FROM LUMBINI - Indra Prasad Bhusal4 Abstract The main objective of the article is to identify the basic elements of Buddhists Economics applicable to fiscal decentralization. The study reviews the Buddhists Economics and Fiscal Decentralization from global perspective. Fiscal decentralization is the process to deliver the power and resources to the grass root level of governance. If the governing body is able to impose the Buddha’s ideology in the policy, certainly resource allocation conflict will be minimized. Methodologically the researcher has conducted interaction programs among Buddhists economists, scholars and academicians available in Lumbini– the birth place of Buddha. The author has analyzed the facts matching with literature review and focused group discussion in Lumbini. The study has identified elements of fiscal decentralization from Buddhist Economics. These elements can be a guideline for noble scholars, academicians, researchers and policy makers of fiscal decentralization from Buddhists economics. Key Words: Buddhists Economics, Fiscal Decentralization, Lumbini Background This attempt is a study of fiscal decentralization in Buddhists Economics in development economics. Fiscal decentralization constitutes the public finance dimension to decentralization in general, defining how the expenditures and revenues are organized between and across different levels of government in the national polity. The precise nature of intergovernmental fiscal relations and fiscal decentralization policy in any given country varies depending on how sub-national government and administration is organized (UNDP, 2005). Fiscal decentralization should be considered as intergovernmental fiscal relations that show how different level of governments acts and interacts with each other on fiscal issues i.e. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 January 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Chatzidakis, A. and Larsen, G. and Bishop, S. (2014) 'Farewell to consumerism : countervailing logics of growth in consumption.', Ephemera : theory and politics in organization., 14 (4). pp. 753-764. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/farewell-consumerism-countervailing-logics-growth- consumption Publisher's copyright statement: Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk the author(s) 2014 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org volume 14(4): 753-764 Farewell to consumerism: Countervailing logics of growth in consumption Andreas Chatzidakis, Gretchen Larsen and Simon Bishop Introduction The logic of growth is dominant in the contemporary political economy and in various notions of social and cultural prosperity (e.g. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Contemplation for Economists. Towards a Social Economy Based on Empathy and Compassion

Krzysztof T. Konecki 11 ISSN 2071-789X GUEST EDITORIAL Konecki, K. T. (2017). Contemplation for Economists. Towards a Social Economy Based on Empathy and Compassion. Economics and Sociology, 10(3), 11- 24. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-3/1 Krzysztof T. Konecki, CONTEMPLATION University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland, FOR ECONOMISTS. TOWARDS E-mail: [email protected] A SOCIAL ECONOMY BASED ON EMPATHY AND COMPASSION ABSTRACT. The goal of the paper is to present the Buddhist approach to the economy and what we can learn Received: December, 2016 from it. It demonstrates David Loy’s analysis of the 1st Revision: March, 2017 meaning of money from the Buddhist perspective. Money Accepted: June, 2017 becomes a reality symbol and an ego symbol. The paper also presents some conclusions from analysis of Buddhist prescriptions to the economic system according to Frederic Pryor. Stress is put on compassion and ethics, which show the ubiquitous interconnectedness that works for the well- DOI: 10.14254/2071- being of the whole society/societies. The Buddhist 789X.2017/10-3/1 approach to the economy is connected with pro-social values and compassion, and this paper looks at the contemporary economy and society from this point of view. Contemporary organizations are based on the greed, which is a feature not only of individuals but also of institutions (institutionalized greed). Work on the self-ego is an important practice (contemplation, mindfulness practice and meditation) in limiting or eliminating greediness in the social and economic system in which we are immersed, but usually not aware of. JEL Classification: A13, Z13 Keywords: Buddhism; economy; money; institutionalized greed; meditation; contemplation. -

Krugman's Growthism

World Economics Association BOOK SERIES Essays against growthism by Herman Daly 2 WEA Book series Essays against growthism by Herman Daly Copyright © 2015 Herman Daly All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-911156-27-7 Published by World Economics Association http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/ Cover artwork taken from Tree Nursery by Paul Klee 1929. __________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher. Herman Daly About the book When I worked at the World Bank, I often heard the statement, “There is no conflict between economics and ecology. We can and must grow the economy and protect the environment at the same time.” I still hear that a lot today. Is it true? Is it possible? Although it is a comforting idea, I fear that it is at most half true. The “true” part comes from a confusion of reallocation with aggregate growth. There are generally always possibilities of better allocation – more of something desired in exchange for a reduction in something less desired. This is the domain of microeconomics. Aggregate growth, by contrast, means more of everything as measured by GDP – it is the domain of macroeconomics, and is the meaning of growth in this discussion. The economy is an open subsystem of the larger ecosphere that is finite, non- growing, and materially closed, although open to a continual, but non-growing, throughput of solar energy. When the economy grows in physical dimensions it incorporates matter and energy from the rest of the ecosystem into itself. -

Green Growth Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: the Alternative Solution for Achieving the Balance Between Both the Natural and the Economic System

sustainability Editorial Green Growth Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: The Alternative Solution for Achieving the Balance between Both the Natural and the Economic System Diego A. Vazquez-Brust 1,2 and José A. Plaza-Úbeda 3,* 1 Portsmouth Faculty of Business and Law, Richmond Building, Portland Street, Portsmouth P01 3DE, UK; [email protected] 2 Production Engineering Department, Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis 88040-900, SC, Brazil 3 Economics and Business Department, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] 1. Introduction “We are ethically obliged and incited to think beyond what are treated as the realistic limits of the possible” (Judith Butler, 2020) The existence of an imbalance between our planet’s reserves of resources and the conditions necessary to maintain high levels of economic growth is evident [1]. The limitation of natural resources pushes companies to consider the possibility of facing critical situations in the future that will make it extremely difficult to reconcile economic Citation: Vazquez-Brust, D.A.; and sustainable objectives [2]. Plaza-Úbeda, J.A. Green Growth In this context of dependence on an environment with finite resources, there are Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: growing interests in alternative economic models, such as the Circular Economy, oriented to The Alternative Solution for the maximum efficient use of resources [3–5]. However, the Circular Economy approach is Achieving the Balance between Both still very far from the reality of industries, and the depletion of natural resources continues the Natural and the Economic System. undeterred [6]. It is increasingly necessary to explore alternative approaches to address the Sustainability 2021, 13, 4610. -

Degrowth ‘From Below’? the Role of Urban Social Movements in a Post-Capitalist Transition

_ Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute Degrowth ‘from below’? The role of urban social movements in a post-capitalist transition Research Paper Degrowth ‘from below’? The role of urban social movements in a post-capitalist transition Research Paper No. 6, March 2019 MSSI’s Research Papers series is aimed at showcasing new and exciting sustainability knowledge. The papers are referenced and are subject to an internal academic review process. The Institute hopes this scholarship will stimulate thought and discussion within the University of Melbourne and in the broader community. Authors Dr Samuel Alexander is a Research Fellow with the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute and a lecturer with the Office for Environmental Programs, University of Melbourne. He is the author of thirteen books, including Degrowth in the Suburbs (2019, co-authored with Brendan Gleeson), Wild Democracy (2017), Prosperous Descent (2015) and Sufficiency Economy (2015). Professor Brendan Gleeson is the Director of the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, at the University of Melbourne. Brendan has made significant scholarly contributions in urban and social policy, environmental theory and policy. He is the author or editor of fourteen books, three of which have won national and international prizes, and numerous journal articles. Acknowledgements Thanks to John Wiseman and Robert Perey for sharing very helpful feedback on a draft of this paper. Cover Image Photo credit: permablitz.sintra 02 17042011 121/flickr/creative commons Citing this paper Please cite this paper as Alexander, S. and Gleeson, B. 2019, Degrowth ‘from below’? The role of urban social movements in a post-capitalist transition, MSSI Research Paper, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne. -

A Decolonial Critique of Liberal Modern Buddhist Social Movements

Utopic Colonies A Decolonial Critique of Liberal Modern Buddhist Social Movements Shaun Terry Acknowledgements I strongly believe that no work is ever truly original and no one is ever very responsible for any production. I can certainly say that my work has depended on ideas borrowed, as well as on valuable discussions and interrogations in concert with other people. If I weren’t so lucky for the valuable thoughts and affects of so many people in my life, this project could not be as it is. There are many people for whom I must express deep gratitude. The first person that I must thank is Lauren Leve. I approached her to be my advisor for what became this project (and, initially, was not at all this project). I did not know her at all, other than having been in a couple-hours lecture that she gave. She was hesitant to take on what I (ambiguously, probably confusingly) proposed, but I am incredibly grateful that she took the leap of faith required to help me to manifest this work. It was always necessarily the case that I would not be perfectly prepared to take on something like Buddhism’s subversive potential in liberal modernity, but Lauren pointed me toward resources and showed infinite patience in dealing with my seemingly boundless ignorance. My spontaneous and curious nature tends to bend me toward the circuitous and this project is surely not what Lauren had in mind; there likely are tensions between her work and what I here present. Yet, she has been open-minded and helpful in leading me toward the improved versions of arguments that appear in what I here lay out. -

Recognition of Unpaid Work from the Perspective of Degrowth

Ecological Economics 84 (2012) 240–246 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Ecological Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon “This is a bit of the good life”: Recognition of unpaid work from the perspective of degrowth Linda Nierling ⁎ Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis, Hermann-von-Helmholtz-Platz 1, 76344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany article info abstract Article history: The decommodification of work activity is central for conceiving work from a degrowth perspective. Yet per- Received 9 January 2011 sonal dependence on paid work is very high, whereas unpaid work activity, such as providing care, commu- Received in revised form 28 October 2011 nity service and subsistence, continues to be neglected by individuals and society. By using the analytical Accepted 31 October 2011 approach related to recognition as employed by Axel Honneth, I argue on the basis of empirical findings Available online 17 February 2012 that unpaid work can play a significant role in one's personal well-being at the individual level. With regard to the transition process towards a society of degrowth, however, a key seems to be a change in the norma- Keywords: Degrowth tive paradigm concerning work at the individual level. Unpaid work © 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Recognition Sustainability End of work Qualitative case study research 1. Introduction Challenging in this respect is the question of how these benefits can be introduced in society and in households. A major factor Following the conceptualisation of “degrowth”1 summarised in seems to be the organisation and the societal conception of work. -

Sustainable Consumption Transitions Series Issue 6

In cooperation with Sustainable Consumption Transitions Series Issue 6 SCORAI Europe Workshop Proceedings Sustainable Consumption and Social Justice in a Constrained World SCORAI Europe Workshop August 29/30, 2016, Budapest, Hungary In collaboration with: Resource Cap Coalition Ombudsman for Future Generations, Hungary SCORAI Steering Committee: Julia Backhaus, Maastricht University, NL Janis Brizga, NGO Green Liberty & University of Latvia, Latvia Frances Fahy, NUI Galway, Ireland Audley Genus, Kingston University, UK Sylvia Lorek, Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Germany Henrike Rau, University of Munich, Germany Marlyne Sahakian, University of Lausanne, Switzerland Edina Vadovics, GreenDependent Institute, Hungary Workshop organizing team: Klára Hajdú, Resource Cap Coalition, Hungary Sylvia Lorek, Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Germany Barbara Muraca, Oregon State University Marlyne Sahakian, IPTEH, The University of Lausanne, Switzerland Edina Vadovics, GreenDependent Institute, Hungary Philip Vergragt, Tellus Institute & Clark University The workshop was organized with the financial assistance of the European Union within the project "Time for change: Promoting sustainable consumption and production of raw materials in the context of EYD 2015 and beyond". The contents of this event are the sole responsibility of organisers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Please cite as: Lorek S., Vadovics E. (Ed.) (2016). Sustainable Consumption and Social Justice in a Constrained -

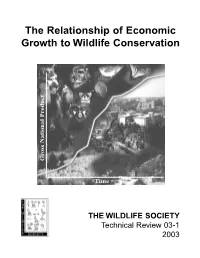

Tech Rev 03-1 for PDF.Qxd

The Relationship of Economic Growth to Wildlife Conservation Gross National Product Gross Time THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY Technical Review 03-1 2003 THE RELATIONSHIP OF ECONOMIC GROWTH TO WILDLIFE CONSERVATION The Wildlife Society Members of the Economic Growth Technical Review Committee David L. Trauger (Chair) Pamela R. Garrettson Natural Resources Program Division of Migratory Bird Management Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Virginia Center 11500 American Holly Drive 7054 Haycock Road Laurel, MD 20708 Falls Church, VA 22043 Brian J. Kernohan Brian Czech Boise Cascade Corporation National Wildlife Refuge System 2010 South Curtis Circle U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Boise, ID 83705 4401 North Fairfax Drive, MS 670 Arlington, VA 22203 Craig A. Miller Human Dimensions Research Program Jon D. Erickson Illinois Natural History Survey School of Natural Resources 607 East Peabody Drive Aiken Center Champaign, IL 61820 University of Vermont Burlington, VT 05405 Edited by Krista E. M. Galley The Wildlife Society Technical Review 03-1 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 200 March 2003 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Foreword Presidents of The Wildlife Society occasionally appoint ad hoc committees to study and report on select conservation issues. The reports ordinarily appear as either a Technical Review or a Position Statement. Review papers present technical information and the views of the appointed committee members, but not necessarily the views of their employers. Position statements are based on the review papers, and the preliminary versions are published in The Wildlifer for comment by Society members. Following the comment period, revision, and Council's approval, the statements are published as official positions of The Wildlife Society. -

Historical and Critical Review on Biophysical Economics 1

July 21, 2016 9:55 WSPC/S1793-0480 204-BRL 1630001 Biophysical Reviews and Letters Vol. 11, No. 2 (2016) 63–86 c World Scientific Publishing Company DOI: 10.1142/S1793048016300012 Historical and Critical Review on Biophysical Economics Yekbun Adig¨uzel Department of Biophysics, School of Medicine Istanbul Kemerburgaz University Kartaltepe Mah. Incirli Cad. No:11 Bakirkoy, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Received 18 March 2016 Revised 25 April 2016 Accepted 3 May 2016 Published 21 July 2016 Biophysical economics is initiated with the long history of the relation of economics with ecological basis and biophysical perspectives of the physiocrats. It inherently has social, economic, biological, environmental, natural, physical, and scientific grounds. Biological entities in economy like the resources, consumers, populations, and parts of production systems, etc. could all be dealt by biophysical economics. Considering this wide scope, current work is a “biophysical economics at a glance” rather than a comprehensive review of the full range of topics that may just be adequately covered in a book-length work. However, the sense of its wide range of applications is aimed to be provided to the reader in this work. Here, modern approaches and biophysical growth theory are pre- sented after the long history and an overview of the concepts in biophysical economics. Examples of the recent studies are provided at the end with discussions. This review is also related to the work by Cleveland, “Biophysical Economics: From Physiocracy to Ecological Economics and Industrial Ecology” [C. J. Cleveland, in Advances in Bioeconomics and Sustainability: Essay in Honor of Nicholas Gerogescu-Roegen,eds.