Museums, Cultural Heritage and Diverse Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Landscape Institute Technical Guidance Note Public ConsuDRAFTltation Draft 2018-06-01 To the recipient of this draft guidance The Landscape Institute is keen to hear the views of LI members and non-members alike. We are happy to receive your comments in any form (eg annotated PDF, email with paragraph references ) via email to [email protected] which will be forwarded to the Chair of the working group. Alternatively, members may make comments on Talking Landscape: Topic “Photography and Photomontage Update”. You may provide any comments you consider would be useful, but may wish to use the following as a guide. 1) Do you expect to be able to use this guidance? If not, why not? 2) Please identify anything you consider to be unclear, or needing further explanation or justification. 3) Please identify anything you disagree with and state why. 4) Could the information be better-organised? If so, how? 5) Are there any important points that should be added? 6) Is there anything in the guidance which is not required? 7) Is there any unnecessary duplication? 8) Any other suggeDRAFTstions? Responses to be returned by 29 June 2018. Incidentally, the ##’s are to aid a final check of cross-references before publication. Contents 1 Introduction Appendices 2 Background Methodology App 01 Site equipment 3 Photography App 02 Camera settings - equipment and approaches needed to capture App 03 Dealing with panoramas suitable images App 04 Technical methodology template -

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom: Collections Development Policy

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom: Collections development policy 1 Collections development policy Name of museum: Doncaster Museum Service Name of governing body: Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: January 24th 2013 Date at which this policy is due for review: January 2018 1. Museum’s statement of purpose The Museum Service primarily serves those living in the Doncaster Metropolitan Borough area and those connected to the King‟s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry* and believes that its purpose can by summed up in four words : Engage, Preserve, Inspire, Communicate * The King‟s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Museum has its own Collections Development Policy, but is included in the 2013-16 Forward Plan and therefore the Museum Service‟s statement of purpose. 2. An overview of current collections. Existing collections, including the subjects or themes and the periods of time and /or geographic areas to which the collections relate 2.0 At present (2012) the following collections have a member of staff with expertise in that particular field. Social History (including costume and photographs) Archaeology (Including Antiquities) World Cultures Fine and Decorative Arts Other collections are not supported by in-house expertise. For these we would actively look to recruit volunteers or honorary curators with knowledge relevant to these collections. We would also look to apply for grants to take on a temporary staff member to facilitate the curation of these collections. We would also look at accessing external expertise and working in partnership with other organisations and individuals. -

City Art Gallery -': & Templenewsam House,::Q the Libraries 4 Arts (Art Gallery 4 Temple Newsam House) Sub-Committee

CITY ART GALLERY -': & TEMPLENEWSAM HOUSE,::Q THE LIBRARIES 4 ARTS (ART GALLERY 4 TEMPLE NEWSAM HOUSE) SUB-COMMITTEE The Lord Mayor Chairman Councillor A. Adamson Deputy Chairman Mrs. Gertrude Ha!hot, J.P. Alderman J. Croysdale Councillor Z. P. Fernandez Advisory Members Alderman L. Hammond Councillor A. M. M. Happold Mr. Edmund Arnold Alderman C. Jenkinson, M.A., LL.B. Councillor F. E. Tetley, D.S.O. Mr. C. H. Boyle, J.P. Alderman Sir G. Martin, K.B.E.,J.P. Councillor G.A. Stevenson Professor B. Dobree, O.B.E. Councillor H. S. Vick, J.P. Councillor H. Bretherick Peacock Councillor D. Murphy, J.P. Mr. L. W. K. Fearnley Mr. H. P. Councillor W. Shutt Lady Martin Mrs. J. S. Walsh Councillor D. Kaberry Mr. E. Pybus Mrs. R. H. Blackburn Director Mr. E. I. Musgrave THE LEEDS ART COLLECTIONS FUND President The Rt. Hon. the Earl of Halifax, K.G., O.M., G.C.S.I.,G.C.I.E. Vice-President Mr. Charles Brotherton, J.P. Trustees Mr. Edmund Arnold Professor Bonamy Dobree, O.B.E. Major Le G. G. W. Horton-Fawkes Committee Councillor A. Adamson Professor Bonamy Dobree, O.B.E. Mr. Edmund Arnold (Hon. Treasurer) Major Le G. G. W. Horton-Fawkes Mr. George Black Mr. E. I. Musgrave (Hon. Secretary) Ali Communications to the Hon. Secretary at Temple Newsam House, Leeds Subscrlptions for the Arts Calendar should be sent to Temple Newsam House 1/6 per issue (postage 1 ') 6/6 per annum, post free Single copies from W. H. Smith and other book shops inter Xiiniber 1947 THE LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR IN THIS ISSUE disturbing intrusions can be removed with- left the EDITORIAL —PICTURE CLEANING out interfering with what is of original. -

Hello Sunshine!

LOCAL INFORMATION for parents of 0-12 year olds in HUDDERSFIELD DEWSBURY HALIFAX BRIGHOUSE TODMORDEN LITTLEBOROUGH OLDHAM ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE SADDLEWORTH ello Sunshi H ne! what's on over the summer Huddersfield Giants’ EORL CRABTREE plus NEWS FAMILY LIFE EDUCATION CLASSES FREE TAKE A COPY ISSUE 39 JUL/AUG 2017 Project Sport Summer Camps 2017 in Huddersfield and Halifax tra Tim ount • x e sc S E i a e D v e e r g F 1 n 0 i l % b i Book a camp of your choice: S Adventure Day • Bubble Sports Olympics •Archery and Fencing Summer Sports • Cricket • Football 10% OFF WITH CODE FAM2017 Book online 24/7 at projectsport.org.uk StandedgeGot (FMP)_Layout a question? 1 11/05/2017 Call us on 10:20 07860 Page 367 1 031 or 07562 124 175 or email [email protected] Standedge Tunnel & Visitor Centre A great day out come rain or shine. Explore the longest, deepest and highest canal tunnel in Britain on a boat trip, enjoy lunch overlooking the canal in the Watersedge Café and let little ones play in the FREE indoor soft play and outdoor adventure areas. Visit canalrivertrust.org.uk/Standedge for more information or telephone 01484 844298 to book your boat trip. EE FR Y PLA S! AREA @Standedge @Standedge 2 www.familiesonline.co.uk WELCOME School's out for the summer! This is the first Summer where I’ll have both children for the full holiday, which is going to be interesting! There are lots of family attractions right on our doorstep, from theme parks, museums and nature reserves, to holiday camps and clubs where kids can take part in a whole array of activities. -

Heritage for All: Ethnic Mi

ICME papers 2001 Paper presented at the ICME sessions ICOM TRIENNIAL CONFERENCE, BARCELONA, 2-4 July, 2001 Heritage for All: ethnic minority attitudes to museums and heritage sites Barbara Woroncow, Chief Executive, Yorkshire Museums Council, United Kingdom Introduction For well over a decade, museums in the United Kingdom have been aware that their services need to be made more accessible to the growing number of ethnic minority communities across the country. Many individual museum services, especially those in areas with significant ethnic minority populations, have undertaken much good work in building relationships, developing relevant exhibitions and activities, and initiating collecting policies and recording systems to present and preserve the traditions and experiences of ethnic minority communities. Examples of such good practice can be found, for example, in Bradford, Halifax and Rotherham, all of which are in the Yorkshire region in the north-east of England. However, the majority of work undertaken by such museum services has been project-based, often with special funding, and has concentrated on dealing with the heritage of individual ethnic minority communities. Such initiatives have been valuable in encouraging many first-time attenders for whom museum-going may not have been a traditional family activity. It is obvious for example, that a special exhibition on Sikh culture, developed in partnership with the Sikh community, is likely to attract Sikh families, as well as a range of other visitors. In some larger cities such as Birmingham and Liverpool, ethnic minority communities have also participated in developing permanent galleries on broader subjects such as rites of passage and slavery. -

TOM HUNTER Born 1965, Dorset Currently Lives and Works in London

TOM HUNTER Born 1965, Dorset Currently lives and works in London EDUCATION 1997 MA, Royal College of Art 1994 BA, The London College of Printing, First Class Honours SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Flaneur EU, Format Festival, Derby, UK Searching For Ghosts, V&A’s Museum of Childhood, London, UK 2016 Life and Death in Hackney, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. USA 2015 a sideshow of a sideshow, Darat al Funun, Amman, Jordan Holly Street Estate, Peer Gallery, London Unheralded Stories, Sundsvall Museum, Sweden Axis Mundi, Green on Red, Dublin 2014 On The Road, LCC, London 2013 Axis Mundi, Purdy Hicks Gallery, London Tom Hunter, Paris Photo Findings, Birmingham Central Library, Birmingham, UK Unheralded Stories, Mission Gallery, Swansea, UK Public Spaces, Public Stages, Print House Gallery, London 2012 Tom Hunter; A Midsummer Night’s Dream, RSC, The Roundhouse, London Punch and Judy, Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood, London 2011 Unheralded Stories, Green on Red Gallery, Dublin Tom Hunter: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford upon Avon 2010 A Palace for Us, Serpentine Gallery, London 2009 Tom Hunter, Galeria 65, Warsaw, Poland Tom Hunter, Pauza Gallery, Krakow, Poland Flashback, Museum of London, London A Journey Back, The Arts Gallery, London 2008 Interior Lives, Geffrye Museum, London Halloween Horror, Culture House, Skovde, Sweden Shopkeepers, Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood, London Life and Death in Hackney, Fotografins Hus, Konstnarshuset, Stockholm Travellers, The Research Gallery, London College -

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience Jennifer L. Lindsay Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2010 ©2010 Jennifer Laurel Lindsay All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.............................................................................................iii PREFACE........................................................................................................................... x ACKNOWLDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... xiv INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1. CRANBROOK: “[A] RESEARCH INSTITUTION OF CREATIVE ART”............................................................................................................ 11 Part 1. Founding the Cranbrook Academy of Art............................................................. 11 Section 1. Origins of the Academy....................................................................... 11 Section 2. A Curriculum for Modern Artists in Modern Times ........................... 16 Section 3. Cranbrook’s Landscape and Architecture: “A Total Work of Art”.... 20 Part 2. History of Weaving and Textiles at Cranbrook..................................................... 23 -

DIY-No3-Bookbinding-Spreads.Pdf

AN INTRODUCTION TO: BOOKBINDING CONTENTS Introduction 4 The art of bindery 4 A Brief History 5 Bookbinding roots 5 Power of the written word 6 Binding 101 8 Anatomy of the book 8 Binding systems 10 Paper selection 12 Handling paper 13 Types of paper 14 Folding techniques 14 Cover ideas 16 Planning Ahead 18 Choosing a bookbinding style for you 18 The Public is an activist design studio specializing in Worksheet: project management 20 changing the world. Step-by-step guide 22 This zine, a part of our Creative Resistance How-to Saddlestitch 22 Series, is designed to make our skill sets accessible Hardcover accordion fold 24 to the communities with whom we work. We Hardcover fanbook with stud 27 encourage you to copy, share, and adapt it to fit your needs as you change the world for the better, and to Additional folding techniques 30 share your work with us along the way. Last words 31 Special thanks to Mandy K Yu from the York-Sheridan Design Program in Toronto, for developing this zine What’s Out There 32 on behalf of The Public. Materials, tools, equipment 32 Printing services 32 For more information, please visit thepublicstudio.ca. Workshops 33 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this Selected Resources 34 license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. Online tutorials 34 Books & videos 34 About our internship program Introduction Bookbinding enhances the A brief history presentation of your creative project. You can use it to THE ART OF BINDERY BOOKBINDING ROOTS Today, bookbinding can assemble a professional portfolio, be used for: Bookbinding is a means for a collection of photographs or Long before ESS/ producing, sharing and circulating recipes, decorative guestbook, R the modern • portfolios • menus independent and community or volume of literature such as G-P Latin alphabet • photo albums • short stories • poetry books • much more work for artistic, personal or a personal journal or collection RINTIN was conceived, • journals commercial purposes. -

The Patten Pages the William Patten Newsletter for Parents and Children

The Patten Pages The William Patten Newsletter for Parents and Children th Issue 86 Friday 9 October 2015 We have had another busy few weeks at Roman Day William Patten and we still have a lot to fit Spending the whole day as a Roman might sound in before half term! Please check the like a lot of fun but Year 4 proved recently that it's also quite hard work! They learnt Latin, wrote on calendar on the school website for details wax tablets instead of paper and discovered how of upcoming events. to read and write Roman numerals. Then everyone had a go at making their own Roman Hackney Museum workshop shield and mosaic before joining in with a Roman Yesterday, Year 1 had a visitor from Hackney banquet. Our Roman ancestors would have been proud! Museum who brought along a million year old fossil found on Stoke Newington common and a piece of ancient pottery found in Dalston. She also brought along four very different suitcases, belonging to four very different people, who had all moved to Hackney. We had to look at the clues in each suitcase and act as detective teams to find out who they were and why they had left their homes to move here. Mary Vance had moved in the 60s on the Windrush from Trinidad to become a bus conductor. A Victorian Mary had left Yorkshire in search of work as a maid in smoggy London. Mohammed had fled civil war in Sierra Leone in the 90s. Conrad Loddiges All about Me moved from Germany to a 1798 version of Both nursery classes have been learning about Hackney, full of green fields, and had started a our half term topic of "All about me". -

Biology Curators Group Newsletter Vol 2 No 9.Pdf

ISSN 0144 - 588x BIOLOGY CURATORS' 11 GROUP Newsletter Vol.2 No.9 February 1981 POTTERS MUSEUM OF CURIOSITY 6 HIGH STREET, ARUNDEL POTTERS MUSEUM OF CURIOSITY, 6 High Street (James Cart/and Esq.). Life work of the Victorian naturalist and taxidermist, Waiter Potter, plus numer ous curiosities from all over the world. Easter to November 1: daily 10.30-1, 2.15--5.30 approximately. Admission 35p, Children 15p, O.A.Ps. 25p. Special rates for parties. Tel. 0903 882420 (evenings 883253) Founded at Bramber, Sussex, 118 years ago by Waiter Potter, the ta11: idermist and natu r~ li s l. His life's work can be seen in the unique animal Tableaux-Kittens Wedding, Rabbits School, Death of Cock Robin, etc., also exhibits of natural history and numerous curios found locally and abroad. Often see n on TV and in the Press and one of the last truly Victorian Museums in tlle Country. Guide Book and History POTTER'S MUSEUM and of EXHIBITION l<'amous for its unique collection of animal tableaux Potfep's ].iuseum t he life work of one man. and Exhibition OPE NING TIMES Easter until the end of Oc tober BRAMBER. STEYNING. SUSSEX (including Bank H olidays) . 10 a . m. until 1 p.m.; . 2.15 p.m. until dusk or 6 p. m ., whichever is the earlier. Closed on Sundays. D uring the winter the Museum is closed on Sundays, Tuesdays, Ch ristmas Day and at such other times as may be necessary for m aintenance purposes. Visitors from a distance are advised to make inquiries before hand. -

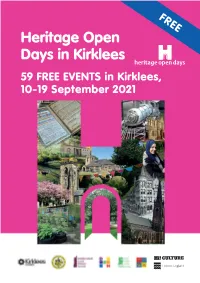

Heritage Open Days in Kirklees

FREE Heritage Open Days in Kirklees 59 FREE EVENTS in Kirklees, 10-19 September 2021 Discover inspirational stories, stunning art & heritage at Kirklees Museums & Galleries • Fascinating exhibitions • Relaxing gardens & parks • Great coffee & unique gifts Bagshaw Museum | Batley Oakwell Hall & Country Park | Birstall Tolson Museum | Huddersfield Huddersfield Art Gallery Follow us on Kirklees Museums & Galleries @KirkleesMuseums For further details visit: www.kirklees.gov.uk/museums Discover inspirational stories, About Heritage Open Days stunning art & heritage at Kirklees Museums & Galleries Heritage Open Days is England’s biggest festival of history and culture. Each September, thousands of sites across the country invite you in to explore local treasures of every age, style and function, and many special events are held. It’s your chance to see hidden places and try out new experiences – and it’s all FREE. In 2020 the festival went ahead but was much restricted by the pandemic. While not quite reaching the heights of 2019, this year will see a fuller Kirklees programme and, alongside old favourites, there are over 20 new entries, many of them celebrating this year’s national theme, Edible England. Some events are also part of the Huddersfield High Street Heritage Action Zone cultural programme centred on St George’s Square. All events are organised independently with support from the Kirklees HOD Committee, which has prepared this brochure. Many events are open access but some have to be booked. Bookable events are identified in the brochure with details of how to book (there is no centralised booking system this year). Please respect this: if you don’t book and there are no spaces on the day, you will be turned away. -

Clark's “Love Letters” Exhibition to Display Language As

Clark’s “Love Letters” Exhibition to Display Language as Art Wednesday, October 03, 2012 Jeffrey Starr, GoLocalWorcester Contributor "Timeline" by Don Tarallo Clark University will be holding an almost two month long Fall art exhibition entitled "Love Letters: The Intersection of Art and Design." The exhibition begins Wednesday, October 3 at the Traina Center for the Arts, with an opening reception to kick off the show at the Schiltkamp Gallery in the Traina Center from 5-7 pm. The exhibition will run through November 26. The show will display a wide variety of letter forms in an array of different mediums from a number of different artists. These mediums include video animation, photomontage, ceramic sculpture, drawing and paper collage. "We want to connect people with artists and designers who love letters," said the co-currator of the show Sara Raffo explaining the overall purpose of the show. "We want to create awareness for people who pay attention to typography and letterform." The purpose and uniqueness of the art show will be shown in the imaginative ways the artists play with typographic form and function involving letters. To put simply, the show portrays "letter form as aesthetic", according to Raffo. For those who may not be familiar with the concept of "typography", or the visual aspects of language, as a type of art, Raffo explains. "Typography animates the language and makes it come to life." For the artists involved, the style and form of a letter can convey just as much if not more meaning than words themselves. Words, style and form all combine together to create more meaning in what we read than is often thought.