Teaching Physical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Proceedings

Book of Proceedings AIESEP 2011 International Conference 22-25 June 2011 University of Limerick, Ireland Moving People, Moving Forward 1 INTRODUCTION We are delighted to present the Book of Proceedings that is the result of an open call for submitted papers related to the work delegates presented at the AIESEP 2011 International Conference at the University of Limerick, Ireland on 22-25 June, 2011. The main theme of the conference Moving People, People Moving focused on sharing contemporary theory and discussing cutting edge research, national and international policies and best practices around motivating people to engage in school physical education and in healthy lifestyles beyond school and into adulthood and understanding how to sustain engagement over time. Five sub-themes contributed to the main theme and ran throughout the conference programme, (i) Educating Professionals who Promote Physical Education, Sport and Physical Activity, (ii) Impact of Physical Education, Sport &Physical Activity on the Individual and Society, (iii) Engaging Diverse Populations in Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sport, (iv) Physical Activity & Health Policies: Implementation and Implications within and beyond School and (v) Technologies in support of Physical Education, Sport and Physical Activity. The papers presented in the proceedings are not grouped by themes but rather by the order they were presented in the conference programme. The number that precedes each title matches the number on the conference programme. We would like to sincerely thank all those who took the time to complie and submit a paper. Two further outlets of work related to the AIESEP 2011 International Conference are due out in 2012. -

Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity

Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity 9780230102682_01_previii.indd i 2/11/2010 11:31:56 AM This page intentionally left blank Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity God’s Mission as Word-Event Paul S. Chung 9780230102682_01_previii.indd iii 2/11/2010 11:31:57 AM PUBLIC THEOLOGY IN AN AGE OF WORLD CHRISTIANITY Copyright © Paul S. Chung, 2010. All rights reserved. First published in 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978–0–230–10268–2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chung, Paul S., 1958– Public theology in an age of world Christianity : God's mission as word-event / Paul S. Chung. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–230–10268–2 (alk. paper) 1. Missions—Theory. I. Title. BV2063.C495 2010 266.001—dc22 2009039957 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: April 2010 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America. -

![The American Legion Monthly [Volume 4, No. 2 (February 1928)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8002/the-american-legion-monthly-volume-4-no-2-february-1928-848002.webp)

The American Legion Monthly [Volume 4, No. 2 (February 1928)]

qhMERICAN EGION JOHN ERSKINE - ROBERT W. CHAMBERS HUGH WALPOLE + PERCEVAL GIBBON - HUGH WILEY "Submarine sighted—position 45 BATTLE PLANES leap into action — bined ,180,000 horse power to the propellers springing from a five-acre deck — —enough to drive the ship at 39 miles an sure of a landing place on their return, hour— enough to furnish light and power though a thousand miles from shore. for a city of half a million people. This marvel of national de- And in the familiar occupa- fense was accomplished — and tions of daily life, electricity is duplicated— when the airplane working wonders just as great carrier, U. S.S.Saratoga, and her —improving industrial produc- sister ship, U. S. S. Lexington, tion, lifting the burden of labor, The General Electric Com- were completely electrified. pany has developed pow- speeding transportation, and erful marine equipment, as In each, four General Electric well as electric apparatus multiplying the comforts of for every purpose of public turbine-generators deliver, com- advantage and personal ser- home. vice. Its products are iden- tified by the initials G-E. GENERAL ELECTRIC — ££> Electricity le In Chicago, the electrical center of the world. 2* At a great, practical school* 3. A national institution for 29 years. 4* By actual jobs on a mammoth outlay of eleo trical apparatus. 5. All practical training on actual electrical machinery, 6. No advanced education necessary. 7. Endorsed by many leading electrical concerns. YouLearn byDoing— notReading— at COYNE in 90 Day! Only by actual practical training on every kind of electric apparatus can you become a real Practical Electrician capable of commanding a real salary With such practical training as given at COYNE, you become a real Practical Electrician in 90 days. -

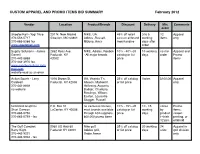

Custom Apparel and Promo Items Bid Chart

CUSTOM APPAREL AND PROMO ITEMS BID SUMMARY February 2012 Vendor Location Product/Brands Discount Delivery Min. Comments order Skeeter Kell - Yogi Trice 207 N. New Madrid NIKE, UA, 45% off retail 3 to 5 12 Apparel 270-559-5717 Sikeston, MO 63801 Adidas ,Russell, cost on all brand working items only 270-665-5088 fax Mizuno, Asics merchandise days after www.skeeterkell.com order Supply Solutions - James 2852 Ross Ave. NIKE, Adidas, Reebok 10% - 40% off 10 working no min Apparel and Garrett Paducah, KY - All major brands catalog or list days order Promo 270-442-8888 42002 price items 270-444-3970 fax www.supplysolutions.logo mall.com website read as an error Action Sports - Larry 1016 Brown St. UA, Virginia Tʼs, 25% off catalog Varies $100.00 Apparel Caldwell Paducah, KY 42003 Alleson, Markwort, or list price only 270-443-8838 Holloway, Augusta, no website Badger, Champro, Rawlings, Wilson, Easton, Louisville Slugger, Russell Unlimited Graphics P.O. Box 10 no exclusive license, 10% - 15% off 10 - 15 varies Promo Shari Damron LaCenter, KY 42056 most brands available catalog or list working by items, 270-665-5750 through ASI suppliers, price days product screen 270-665-5759 - fax 800,000 promo items t-shirts printing, or 12 pcs. embroid The Golf Complex 5980 US Hwy 60 Nike golf, 35% off catalog 20 working 24 Apparel in Barry Kight Paducah KY 42001 Adidas golf, or list price days units golf division 270-442-9221 Under Armor only 270-442-9904 - fax Vendor Location Product/Brands Discount Delivery Min. Comments order Troutman 534 S. -

The Year of Women: >> 100 Years of Coeducation

ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2018 THE YEAR OF WOMEN: >> 100 YEARS OF COEDUCATION WIKI WONDER POCKET FULL OF SUNSHINE OUR TEAM IS READY TO HELP YOU REACH THE TOP OF YOUR GAME. The world has changed. Information fl ow is faster than ever. Remaining at the top of your game requires focus, foresight and the ability to act quickly. We believe to keep moving forward, your team needs the best players: experienced investment professionals who combine sound judgment with innovation. Allow us to assist as you step onto your fi eld. Are you ready? 428 McLaws Circle, Ste. 100 Williamsburg, VA 23185 757-220-1782 • 888-465-8422 www.osg.wfadv.com of Wells Fargo Advisors Joe Montgomery, Judy Halstead, Christine Stiles, Bryce Lee, Robin Wilcox, Cathleen Dillon, Brian Moore, Loughan Campbell, Karen Logan, Vicki Smith, Brad Stewart, James Johnson and Emily Sporrer Securities and Insurance Products • NOT INSURED BY FDIC OR ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY • MAY LOSE VALUE • NOT A DEPOSIT OF OR GUARANTEED BY A BANK OR ANY BANK AFFILIATE Wells Fargo Advisors is a trade name used by Wells Fargo Clearing Services, LLC, Member SIPC. ©2017 Wells Fargo Advisors, LLC 02/18 Your Happily Ever After. Your special day deserves special attention. At an ofcial Colonial Williamsburg Hotel, we cater to your every need during every moment of your wedding experience. Whether you want an intimate or elaborate ceremony, you will fnd the perfect setting for your perfect day here with us. With our horse-drawn carriages, spacious accommodations, championship golf courses, and spa oferings, a wedding here will have everything you need for your happily ever after. -

Delinquent Current Year Real Property

Delinquent Current Year Real Property Tax as of February 1, 2021 PRIMARY OWNER SECONDARY OWNER PARCEL ID TOTAL DUE SITUS ADDRESS 11 WESTVIEW LLC 964972494700000 1,550.02 11 WESTVIEW RD ASHEVILLE NC 1115 INVESTMENTS LLC 962826247600000 1,784.57 424 DEAVERVIEW RD ASHEVILLE NC 120 BROADWAY STREET LLC 061935493200000 630.62 99999 BROADWAY ST BLACK MOUNTAIN NC 13:22 LEGACIES LLC 967741958700000 2,609.06 48 WESTSIDE VILLAGE RD UNINCORPORATED 131 BROADWAY LLC 061935599200000 2,856.73 131 BROADWAY ST BLACK MOUNTAIN NC 1430 MERRIMON AVENUE LLC 973095178600000 2,759.07 1430 MERRIMON AVE ASHEVILLE NC 146 ROBERTS LLC 964807218300000 19,180.16 146 ROBERTS ST ASHEVILLE NC 146 ROBERTS LLC 964806195600000 17.24 179 ROBERTS ST ASHEVILLE NC 161 LOGAN LLC 964784681600000 1,447.39 617 BROOKSHIRE ST ASHEVILLE NC 18 BRENNAN BROKE ME LLC 962964621500000 2,410.41 18 BRENNAN BROOK DR UNINCORPORATED 180 HOLDINGS LLC 963816782800000 12.94 99999 MAURICET LN ASHEVILLE NC 233 RIVERSIDE LLC 963889237500000 17,355.27 350 RIVERSIDE DR ASHEVILLE NC 27 DEER RUN DRIVE LLC 965505559900000 2,393.79 27 DEER RUN DR ASHEVILLE NC 28 HUNTER DRIVE REVOCABLE TRUST 962421184100000 478.17 28 HUNTER DR UNINCORPORATED 29 PAGE AVE LLC 964930087300000 12,618.97 29 PAGE AVE ASHEVILLE NC 299 OLD HIGHWAY 20 LLC 971182306200000 2,670.65 17 STONE OWL TRL UNINCORPORATED 2M HOME INVESTMENTS LLC 970141443400000 881.74 71 GRAY FOX DR UNINCORPORATED 311 ASHEVILLE CONDO LLC 9648623059C0311 2,608.52 311 BOWLING PARK RD ASHEVILLE NC 325 HAYWOOD CHECK THE DEED! LLC 963864649400000 2,288.38 325 HAYWOOD -

March 2016(Pdf)

2016 MARCH — R O C K Y M O UNTAIN SECTION PGA T E E T I M E S July—August 2014 TAYLORMADE-ADIDAS, ASHWORTH GOLf AND ADAMS GOLF AGAIN INSIDE THIS ISSUE TO SPONSOR PRO-PRO SHOOTOUT TaylorMade-Adidas Golf/ Ashworth Continue Sponsorship Of Pro-Pro Shootout - Page 1 Adidas and Ashworth Golf Continue Support - Page 1 Bushnell To Support RMSPGA Pro-Pro Shootout - Page 2 The Rocky Mountain Section PGA, along with TaylorMade-adidas, Ashworth Golf and Adams Golf are pleased to announce that these companies will Omega Continues Support of continue as exclusive title sponsors of the annual Rocky Mountain PGA Pro- RMSPGA Tournament Program - Page 2 Pro Shootout through the 2016 event. The sponsorship continues the successful relationship that has been developed between the Company, the Bridgestone Golf Continues Support Section and its members. of RMSPGA - Page 2 The 2016 TaylorMade-adidas golf/Ashworth Pro-Pro Shootout will be Monday Cleveland Golf /Srixon Continues on rd th as SRC Facility Championship Sponsor and Tuesday, May 23 & 24 , at Pinecrest Golf Course in Idaho Falls, Idaho. - Page 2 As one of the highlights on the Section’s tournament calendar, the event is expecting a full field of 50 teams. Cure Putters and Tifosi Optics Support Chapter Events—Page 2 The Rocky Mountain Section extends its thanks and appreciation to Player Fee Information - Page 3 TaylorMade, Western Regional Sales Manager Jeff Parsons and Sales Representative John Johnson for their support of the Rocky Mountain Section Yellowstone Chapter Spring and its members. Meeting and Education Seminar - Page 3 ADIDAS AND ASHWORTH GOLF CONTINUE SUPPORT Education Opportunities - Page 3 Scholarship Opportunities - Page 3 Boise Golf & Travel Show - Page 4 PGA Compensation Survey - Page 4 Short Shots - Page 4 JC Golf Accessories Ad - Page 5 The Rocky Mountain Section PGA is pleased to announce that adidas and Ashworth is continuing its support of the Rocky Mountain PGA and its Sponsor Listing - Page 6 member professionals. -

Euromentor Journal Studies About Education

EUROMENTOR JOURNAL STUDIES ABOUT EDUCATION Volume IX, No. 4/December 2018 EUROMENTOR JOURNAL 1 “Euromentor Journal” is published by “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University. Address: Splaiul Unirii no. 176, Bucharest Phone: (021) - 330.79.00, 330.79.11, 330.79.14 Fax: (021) - 330.87.74 E-mail: euromentor.ucdc @yahoo.com Euromentor Journal was included in IDB EBSCO, PROQUEST, CEEOL, INDEX COPERNICUS, CEDEFOP GLOBAL IMPACT FACTOR, ULRICH’S PERIODICALS DIRECTORY (CNCS recognized) 2 VOLUME IX, NO. 4/DECEMBER 2018 EUROMENTOR JOURNAL STUDIES ABOUT EDUCATION Volume IX, No. 4/December 2018 EUROMENTOR JOURNAL 3 ISSN 2068-780X Every author is responsible for the originality of the article and that the text was not published previously. 4 VOLUME IX, NO. 4/DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS REFORMING CURRICULA: A PRELIMINARY STUDY IN SHAPING COMMUNICATION SCIENCES PROGRAMS IN ROMANIA ........................................................................................................................ 7 IULIA ANGHEL, ELENA BANCIU THE ROLE OF REIGN IN ASSERTING THE ROMANIAN STATEHOOD REFLECTED IN SCHOOL TEXTBOOKS. FROM THE ROMANIAN MEDIEVAL STATES TO THE ROMANIAN NATIONAL STATE. ..................................................................................................... 16 FLORENTINA BURLACU THE SACRIFICIAL SPIRIT - A BEHAVIORAL PATTERN IN THE POPULAR MENTALITY AND CHRISTIAN FAITH ............................................ 28 GABRIELA RUSU-PĂSĂRIN THE IMPORTANT NEED OF GENERAL ACCOUNTING AND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING ............................................................................ -

Tomatonta Tuntunin Natin

TOMATONTAUS009912027B2 TUNTUNIN NATIN (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 , 912 ,027 B2 Henry et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : Mar . 6 , 2018 ( 54 ) METHOD AND APPARATUS FOR (56 ) References Cited EXCHANGING COMMUNICATION SIGNALS U . S . PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 71 ) Applicant : AT & T INTELLECTUAL 395 ,814 A 1 / 1889 Henry et al . PROPERTY I , LP , Atlanta , GA (US ) 529 ,290 A 11/ 1894 Harry et al . 1 ,721 , 785 A 7 / 1929 Meyer ( 72 ) Inventors: Paul Shala Henry , Holmdel , NJ (US ) ; 1 , 798 ,613 A 3 / 1931 Manson et al. Robert Bennett , Southold , NY (US ) ; 1 , 860 , 123 A 5 / 1932 Yagi Farhad Barzegar , Branchburg , NJ 2 ,058 ,611 A 10 / 1936 Merkle et al . (US ) ; Irwin Gerszberg , Kendall Park , 2 , 106 , 770 A 2 / 1938 Southworth et al. NJ (US ) ; Donald J Barnickel, Flemington , NJ (US ) ; Thomas M . ( Continued ) Willis , III, Tinton Falls , NJ (US ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : AT & T INTELLECTUAL AU 565039 B2 9 / 1987 PROPERTY I, L . P ., Atlanta , GA (US ) AU 582630 B2 4 / 1989 (Continued ) ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 0 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS International Search Report and Written Opinion in PCT/ US2016 / (21 ) Appl. No. : 14 /807 ,232 028417 , dated Jul. 5 , 2016 , 13 pages . (22 ) Filed : Jul. 23 , 2015 (Continued ) (65 ) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner — David S Huang US 2017 /0025728 A1 Jan . 26 , 2017 (74 ) Attorney, Agent, or Firm - Guntin & Gust, PLC ; Robert Gingher (51 ) Int. Ci. H04B 3 / 54 ( 2006 . -

Ashworth College Career Catalog

f Ashworth College 2021 Career Catalog 5051 Peachtree Corners Circle, Suite 200 Norcross, GA 30092 Phone: 1-800-957-5412 Fax: 770-417-3030 [email protected] www.ashworthcollege.edu 1 2021 Career Catalog ~ IMPORTANT ~ This catalog is to be read by all Ashworth College students per student’s enrollment agreement. Important Note: For students enrolled in the Pharmacy Technician Program, it is important that you also read the information that is specific to your program in the applicable Pharmacy Technician Student Handbook at the end of this catalog. Ashworth College 2021 Career Catalog, Third Edition Copyright 2021 Ashworth College. All rights reserved. No part of this catalog and/or materials may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission. Purpose: The Catalog is the official document for all academic policies, practices, and program requirements. The general academic policies and policies govern the academic standards and accreditation requirements to maintain matriculated status and to qualify for a degree, diploma, or certificate. Ashworth has adopted a ‘grandfather clause’ policy such that students have a right to complete their academic programs under the degree requirements that existed at the time of their enrollment, to the extent that curriculum offerings make that possible. If program changes are made that effect student programs of study, every effort will be made to transition students into a new program of study that meets new graduation requirements. Students proceeding under revised academic policies must comply with all requirements under the changed program. Reservation of Rights: Ashworth College reserves the right to make changes to the provisions of this catalog and its rules and procedures at any time, with or without notice, subject to licensing requirements. -

Workbook for Grapevine and La Viña Representatives

A Guide to AA Grapevine The Story of the International Journals of Alcoholics Anonymous And a Workbook for Grapevine and La Viña Representatives AA Grapevine, Inc. 475 Riverside Drive New York, NY 10115 www.aagrapevine.org Click Here for the Table of Contents 2 Responsibility Declaration I am responsible. When anyone, anywhere, reaches out for help, I want the hand of AA always to be there. And for that: I am responsible. AA Preamble Alcoholics Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women who share their experience, strength, and hope with each other that they may solve their common problem and help others to recover from alcoholism. The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking. There are no dues or fees for AA membership; we are self-supporting through our own contributions. AA is not allied with any sect, denomination, politics, organization or institution; does not wish to engage in any controversy, neither endorses nor opposes any causes. Our primary purpose is to stay sober and help other alcoholics to achieve sobriety Copyright © by AA Grapevine, Inc. 3 General Service Conference Advisory Action, 1986: “Since each issue of the Grapevine cannot go through the Conference-approval process, the Conference recognizes the AA Grapevine as the international journal of Alcoholics Anonymous.” © AA Grapevine, Inc. 2013 This workbook is service material, reflecting AA experience shared at the AA Grapevine Office. 4 AA Grapevine Statement of Purpose AA Grapevine is the international journal of Alcoholics Anonymous. Written, edited, illustrated, and read by AA members and others interested in the AA program of recovery from alcoholism, Grapevine is a lifeline linking one alcoholic to another. -

Fleetwood: Or, the New Man of Feeling

Fleetwood: Or, The New Man Of Feeling William Godwin Fleetwood: Or, The New Man Of Feeling Table of Contents Fleetwood: Or, The New Man Of Feeling...............................................................................................................1 William Godwin.............................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 VOL. I.........................................................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER I...................................................................................................................................................3 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER III................................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER IV..............................................................................................................................................13 1....................................................................................................................................................................15 2....................................................................................................................................................................16