Large-Leaved Phlox, Broadleaf Phlox, and Wide-Leaved Phlox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

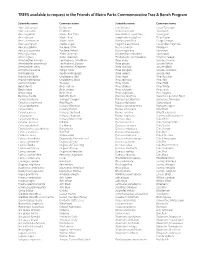

TREES Available to Request in the Friends of Metro Parks Commemorative Tree & Bench Program

TREES available to request in the Friends of Metro Parks Commemorative Tree & Bench Program Scientific name Common name Scientific name Common name Abies balsamaea Fir, Balsam Larix laricina Larch, Tamarack Abies concolor Fir, White Lindera benzoin Spicebush Acer negundo Maple, Box Elder Liquidamber styraciflua Sweetgum Acer rubrum Maple, Red Liriodendron tulipfera Tulip Poplar Acer saccharinum Maple, Silver Maclura pomifera Osage Orange Acer saccharum Maple, Sugar Magnolia acuminata Cucumber magnolia Aesculus glabra Buckeye, Ohio Nyssa sylvatica Blackgum Aesculus octandra Buckeye, Yellow Ostrya viginiana Ironwood Alnus glutinosa Alder, Common Oxydendron arboream Sourwood Alnus rugosa Alder, Speckled Parthenosisis quinquefolia Virginia Creeper Amelanchier arborea Serviceberry, Shadblow Picea abies Spruce, Norway Amelanchier canadensis Serviceberry, Downy Picea glauca Spruce, White Amelanchier laevis Serviceberry Allegheny Picea mariana Spruce, Black Amopha frutocosa Indigo, False Picea pungens Spruce, Colorado Aralia spinosa Devils-walkingstick Picea rubens Spruce, Red Aronia arbutifolia Chokeberry, Red Pinus nigra Pine, Austrian Aronia melancarpa Chokeberry, Black Pinus resinosa Pine, Red Asimina triloba Pawpaw Pinus rigida Pine, Pitch Betula lenta Birch, Yellow Pinus strobus Pine, White Betula lutea Birch, Sweet Pinus sylvestris Pine, Scots Betula nigra Birch, River Pinus virginiana Pine, Virginia Buddeia davidii Butterfly Bush Platanus acerifolia Sycamore, London Plane Campsis radicans Trumpet Creeper Platanus occidentalis Sycamore, -

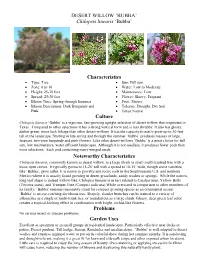

DESERT WILLOW 'BUBBA' Chilopsis Linearis 'Bubba' Characteristics

DESERT WILLOW ‘BUBBA’ Chilopsis linearis ‘Bubba’ Characteristics Type: Tree Sun: Full sun Zone: 6 to 10 Water: Low to Moderate Height: 25-30 feet Maintenance: Low Spread: 25-30 feet Flower: Showy, Fragrant Bloom Time: Spring through Summer Fruit: Showy Bloom Description: Dark Burgundy and Tolerate: Drought, Dry Soil Pink Texas Native Culture Chilopsis linearis ‘Bubba’ is a vigorous, fast-growing upright selection of desert willow that originated in Texas. Compared to other selections it has a strong vertical form and is less shrubby. It also has glossy, darker green, more lush foliage than other desert willows. It has the capacity to easily grow up to 30 feet tall in the landscape. Starting in late spring and through the summer ‘Bubba’ produces masses of large, fragrant, two-tone burgundy and pink flowers. Like other desert willows ‘Bubba’ is a great choice for full sun, low maintenance, water efficient landscapes. Although it is not seedless, it produces fewer pods than most selections. Each pod containing many winged seeds. Noteworthy Characteristics Chilopsis linearis, commonly known as desert willow, is a large shrub or small multi-trunked tree with a loose open crown. It typically grows to 15-25’ tall with a spread to 10-15’ wide, though some varieties, like ‘Bubba’, grow taller. It is native to gravelly and rocky soils in the Southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico where it is usually found growing in desert grasslands, sandy washes or springs. While the narrow, long leaf shape is indeed willow-like, Chilopsis linearis is in fact related to Catalpa trees, Yellow Bells (Tecoma stans), and Trumpet Vine (Campsis radicans).While oversized in comparison to other members of its family, ‘Bubba’ remains reasonably sized for compact growing spaces as an ornamental accent. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Trumpet Creeper (Campsis Radicans) Control Herbicide Options

Publication 20-86C October 2020 Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans) Control Herbicide Options Dr. E. David Dickens, Forest Productivity Professor; Dr. David Clabo, Forest Productivity Professor; and David J. Moorhead, Emeritus Silviculture Professor; UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources BRIEF Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), also known as cow itch vine, trumpet vine, or hummingbird vine, is in the Bignoniaceae family and is native to the eastern United States. Trumpet creeper is frequently found in a variety of southeastern United States forests and can be a competitor in pine stands. If not controlled, it can kill the trees it grows on by canopying over the crowns and not allowing adequate sunlight to get to the tree’s foliage for photo- synthesis. Trumpet creeper is a deciduous, woody vine that can “climb” trees up to 40 feet or greater heights (Photo 1) or form mats on shrubs or grows in clumps lower to the ground (Photo 2). The 1 to 4 inch long green leaves are pinnate, ovate in shape and opposite (Photo 3). The orange to red showy flowers are terminal cymes of 4 to 10 found on the plants during late spring into summer (Photo 4). Large (3 to 6 inches long) seed pods are formed on mature plants in the fall that hold hundreds of seeds (Photo 5). Trumpet creeper control is best performed during active growth periods from mid-June to early October in Georgia. If trumpet creeper has climbed up into a num- ber of trees, a prescribed burn or cutting the vines to groundline may be needed to get the climbing vine down to groundline where foliar active herbicides will be effective. -

An Ecological Classification of Groundwater-Fed

ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF GROUNDWATER-FED SEEPAGE WETLANDS OF THE MARYLAND COASTAL PLAIN By Jason W. Harrison Wildlife and Heritage Service Maryland Department of Natural Resources 909 Wye Mills Rd. Wye Mills, Maryland 21679 410-827-8612 ext. 109 [email protected] Wesley M. Knapp Wildlife and Heritage Service Maryland Department of Natural Resources 909 Wye Mills Rd. Wye Mills, Maryland 21679 410-827-8612 ext. 100 [email protected] June 2010 (updated February 2015) Prepared for United States Fish and Wildlife Service Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr. Governor Boyd K. Rutherford Lt. Governor Mark J. Belton Acting Secretary The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. This document is available in an alternative format upon request from a qualified individual with a disability. Toll free in Maryland: 1-877-620-8DNR ext. 3 Out of State call: 1-410-260-8540 TTY users call via the MD Relay www.dnr.maryland.gov Printed on recycled paper Citation: Harrison, J.W., W.M. Knapp. 2010. Ecological classification of groundwater-fed wetlands of the Maryland Coastal Plain. Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Natural Heritage Program, Annapolis, MD. June 2010. 98 pp. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................................. -

Desmodium Cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-Bracted Tick-Trefoil

New England Plant Conservation Program Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-bracted Tick-trefoil Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: Lynn C. Harper Habitat Protection Specialist Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Westborough, Massachusetts For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, 2002 SUMMARY Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon (Fabaceae) is a tall, herbaceous, perennial legume that is regionally rare in New England. Found most often in dry, open, rocky woods over circumneutral to calcareous bedrock, it has been documented from 28 historic and eight current sites in the three states (Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts) where it is tracked by the Natural Heritage programs. The taxon has not been documented from Maine. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, the species is reported but not tracked by the Heritage programs. Two current sites in Connecticut are known from herbarium specimens. No current sites are known from Rhode Island. Although secure throughout most of its range in eastern and midwestern North America, D. cuspidatum is Endangered in Vermont, considered Historic in New Hampshire, and watch-listed in Massachusetts. It is ranked G5 globally. Very little is understood about the basic biology of this species. From work on congeners, it can be inferred that there are likely to be no problems with pollination, seed set, or germination. As for most legumes, rhizobial bacteria form nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of D. cuspidatum. It is unclear whether there have been any changes in the numbers or distribution of rhizobia capable of forming effective mutualisms with D. -

State Natural Area Management Plan

OLD FOREST STATE NATURAL AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN STATE OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION NATURAL AREAS PROGRAM APRIL 2015 Prepared by: Allan J. Trently West Tennessee Stewardship Ecologist Natural Areas Program Division of Natural Areas Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd Floor Nashville, TN 37243 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 A. Guiding Principles .................................................................................................. 1 B. Significance............................................................................................................. 1 C. Management Authority ........................................................................................... 2 II DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................... 3 A. Statutes, Rules, and Regulations ............................................................................. 3 B. Project History Summary ........................................................................................ 3 C. Natural Resource Assessment ................................................................................. 3 1. Description of the Area ....................................................................... 3 2. Description of Threats ....................................................................... -

Podranea Ricasoliana.Pdf

Family: Bignoniaceae Taxon: Podranea ricasoliana Synonym: Pandorea ricasoliana (Tanfani) Baill. Common Name: pink trumpet vine Podranea brycei (N. E. Br.) Sprague Port St. Johns creeper Tecoma brycei N. E. Br. Zimbabwe creeper Tecoma mackenii W. Watson bubblegum-vine Tecoma ricasoliana Tanfani pandorea Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: HPWRA OrgData Designation: H(HPWRA) Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: HPWRA OrgData WRA Score 7 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 401 Produces -

Leersia Virginica Plant Guide

Plant Guide Wildlife: The caterpillars of the butterfly Enodia WHITEGRASS anthedon (Northern Pearly Eye) feed on the foliage of whitegrass. Aside from this, little is known about floral- Leersia virginica Willd. faunal relationships for this species. Plant Symbol = LEVI2 Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Contributed by: USDA NRCS Plant Materials Center, Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current Alderson, West Virginia status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). USDA Native Status: L48 (N), CAN (N). Description General: Grass Family (Poaceae) Whitegrass is a perennial grass that is native to eastern North America. It is 1 – 3 feet tall, branching occasionally; it is erect to spawling and flowers from July to October. Whitegrass is a good example of the kinds of grasses that grow in wooded areas. Such grasses usually have delicate tin- textured foliage and their panicles or racemes are slender and lanky with small spikelets. As a general rule, they are not very showy. Whitegrass is fairly easy to identify because its spikelets are appressed together to form a single row along the upper half of each branchlet. Each spikelet is single-flowered, oblongoid, and often ciliate along the margins of its lemma. Each floret of whitegrass produces only 2 anthers; this is unusual, because most grasses produce 3 anthers per floret. It is easily confused with the non-native and invasive Japanese stilt grass (Microstegium vimineum). Whitegrass may be distinguished from Japanese stilt grass by its lack of a prominent shiny leaf midvein. It has a short life span relative to most other plant species and a moderate growth rate. -

Towards Resolving Lamiales Relationships

Schäferhoff et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:352 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences Bastian Schäferhoff1*, Andreas Fleischmann2, Eberhard Fischer3, Dirk C Albach4, Thomas Borsch5, Günther Heubl2, Kai F Müller1 Abstract Background: In the large angiosperm order Lamiales, a diverse array of highly specialized life strategies such as carnivory, parasitism, epiphytism, and desiccation tolerance occur, and some lineages possess drastically accelerated DNA substitutional rates or miniaturized genomes. However, understanding the evolution of these phenomena in the order, and clarifying borders of and relationships among lamialean families, has been hindered by largely unresolved trees in the past. Results: Our analysis of the rapidly evolving trnK/matK, trnL-F and rps16 chloroplast regions enabled us to infer more precise phylogenetic hypotheses for the Lamiales. Relationships among the nine first-branching families in the Lamiales tree are now resolved with very strong support. Subsequent to Plocospermataceae, a clade consisting of Carlemanniaceae plus Oleaceae branches, followed by Tetrachondraceae and a newly inferred clade composed of Gesneriaceae plus Calceolariaceae, which is also supported by morphological characters. Plantaginaceae (incl. Gratioleae) and Scrophulariaceae are well separated in the backbone grade; Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae appear in distant clades, while the recently described Linderniaceae are confirmed to be monophyletic and in an isolated position. Conclusions: Confidence about deep nodes of the Lamiales tree is an important step towards understanding the evolutionary diversification of a major clade of flowering plants. The degree of resolution obtained here now provides a first opportunity to discuss the evolution of morphological and biochemical traits in Lamiales.