An Assessment of Rastafari and Repatriation Giulia Bonacci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010

Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 “Whatever the cost of our libraries, the price is cheap compared to that of an ignorant nation.” Walter Cronkite Anguilla Library Service Edison L Hughes Library & Educational Complex 1 - 264- 4 9 7 - 2 4 4 1 [email protected] 3 / 3 1 / 2 0 1 1 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 Department of Library Services Annual Report 2010 2 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 CONTENTS 1. Director’s Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………7 2. Information Resources…………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.1 Collection Management 2.2 Circulation and IT 2.3 Patrons 3. Staff Matters……………………………………………………………………………………………………..18 3.1 Management 3.2 Staff Development 3.3 In-House Matters 4. Reaching Out……………………………………………………………………………………………………21 4.1 Schools’ Library Programme 4.2 Cushion Club 4.3 Book of the Week 4.4 Children’s Library Annual Summer Programme 4.5 Exhibitions 5. Physical Environment……………………………………………………………………………………….43 6. Promoting Partnerships…………………………………………………………………………………….48 7. Financial Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………54 8. Going Forward…………………………………………………………………………………………………..55 Appendix 1 Sources of Support………………………………………………………………………………57 Appendix 2 ALS Organisation Chart…………………………………………………………………………60 3 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 2010 At a Glance 464 customers 27,908 items checked out, 5,499 more joined the library, than last year total of library cardholders now 2903 Strategic planning for next 5 years started Community enjoyed remembering Anguillian lore More than through talks, 1,700 Internet exhibitions… bookings including WiFi users Total of 21,820 items in library database “Jolly” summer programme for kids. Over 50 children know more about “jollification” 4 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 MISSION STATEMENT TO PROVIDE CONTEMPORARY, COMPREHENSIVE AND INTEGRATED LIBRARY, ARCHIVES AND INFORMATION SERVICES RELEVANT TO THE SOCIAL, CULTURAL, EDUCATIONAL, BUSINESS AND INFORMATIONAL NEEDS OF THE COMMUNITY. -

Development Aid and Higher Education in Africa: the Need for More Effective Partnerships Between African Universities and Major American Foundations

CODESRIA Bulletin, Nos 1 & 2, 2012 Page 1 Editorial ODESRIA entered the year 2012 with a new Diaspora. Rabat also confirmed a trend that began earlier Executive Committee, a new President and a on; the General Assembly is becoming a great scientific Cnew Vice President, all of whom were elected attraction for scholars around the world. The debates on during the 13th General Assembly of the Council held in climate change, global knowledge divides, higher December 2011 in Rabat, Morocco. The new President education leadership, the "Arab Spring" / "African is Professor Fatima Harrak of the Institute of African Awakening", China-Africa relations, land grabbing, the Studies, Mohammad V Souissi University in Rabat, and future of multilateralism, the meaning of pan Africanism the Vice-President is Prof. Dzodzi Tshikata of the today, international migrations, and other major issues University of Ghana, Legon. The full list of members of were extremely rich, as can be seen in the summary of the new Executive Committee follows this editorial. the report of the General Assembly published in this issue As the 13th President of CODESRIA, Prof. Harrak took of the Bulletin. The full report will also soon be published. over from Prof. Sam Moyo of the Africa Institute of Most of the 200 or so papers presented at the Assembly Agrarian Studies in Harare. CODESRIA, with the are already on the CODESRIA website, and revised guidance of the Executive Committee, achieved quite a versions will be published in special issues of CODESRIA lot, including the launching of new research and policy journals and in the Book Series, as a way of extending dialogue initiatives, the publication of many good books the debates that started in Rabat to the wider scholarly and the launching of a new journal of social science community. -

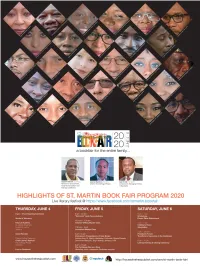

St. Martin Book Fair Program June 4 – 6, 2020

Poster pics of guest authors on the PROGRAM cover | St. Martin Book Fair 2020 L-R, Row 1: Verene Shepherd (Jamaica), Dannabang Kuwabong (Ghanaian/Canadian), Nicole Erna Mae Francis Cotton (St. Martin), Yvonne Weekes (Montserrat/Barbados), Nicole Cage (Martinique), Vladimir Lucien (St. Lucia); Row 2: Ashanti Dinah Orozco Herrera (Colombia), Karen Lord (Barbados), Jean Antoine-Dunne (Trinidad and Tobago/Ireland), Fola Gadet (Guadeloupe), A-dZiko Simba Gegele (Jamaica); Row 3: Richard Georges (Virgin Islands), Sean Taegar (Belize), Jeannine Hall Gailey (USA), Rafael Nino Féliz (Dominican Republic), Stéphanie Melyon-Reinette (Guadeloupe), Fabian Adekunle Badejo (St. Martin); Row 4: Sonia Williams (Barbados), Adrian Fraser (St. Vincent and the Grenadines), Steen Andersen (Denmark), Max Rippon (Marie-Galante, Sirissa Rawlins Sabourin (St. Kitts and Nevis); Row 5: Patricia Turnbull (Virgin Islands), Doris Dumabin (Guadeloupe), René E. Baly (St. Martin/USA), Lili Forbes (St. Martin/USA), Antonio Carmona Báez (Puerto Rico/St. Martin). *** Guest speakers/presenters, L-R: Cozier Frederick (Dominica), Minister for Environment, Rural Modernisation and Kalinago Upliftment; Lorenzo Sanford (Dominica), Chief of the Kalinago People (Dominica); Jean Arnell (St. Martin), Managing Partner and IT Specialist Computech. Click link to see all program activities: www.facebook.com/stmartin.bookfair Purpose and Objectives of the St. Martin Book Fair VISION To be the dynamic platform for books and information on and about St. Martin; establishing an eventful meeting place for the national literature of St. Martin and the literary cultures of the Caribbean; networking with literary cultures from around the world. MISSION STATEMENT To develop a marketplace for the multifaceted and multimedia exhibition and promotion of books, periodicals and publishing technologies and to facilitate St. -

Wisemind Nov2016

“The free exchange of support and ideas is an CONTENTS essential condition to world understanding and equally to world progress." - Haile Selassie 1 Wisemind e-magazine would like to thank PG 3 ….………… OUR EMPEROR SPEAKS all the people who have helped and are helping PG 4 …….... THE GRAND CORONATION to make this magazine a reality. PG 8 ……….………... HOMESCHOOLING: AN IMPORTANT EDUCATION OPTION We would like to take this opportunity to invite ones to submit news, views & opinions, however this invitation PG 11 …………………. ANCIENT SOUNDS does not guarantee immediate publication, but may be PG 14 …………….. AFRICANS LIVE ON A published, also depending upon available space. CONTINENT OWNED BY EUROPEANS! ARTICLES, REASONINGS AND PG 21 …………...... HENRY LOUIS GATES PHOTOGRAPHS CAN BE SENT TO: PG 22 ………… TEACHER ALTHEA - POEM [email protected] PG 24……................. ADVERTISEMENTS THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE CAN BE DOWNLOADED FREE @ TRICESBABY.COM/?P=3041 WISEMINDPUBLICATIONS.COM/NEWS COVER DESIGN: RAS RAVIN-I COVER ART: CHARLES KITTRELL LAYOUT: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH GRAPHIC DESIGN: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: IJAHNYA CHRISTIAN / SIS. JENNIFER BALALA TRANSCRIPTIONS: RAS FLAKO / RAS RAVIN-I CHIEF EDITOR – KATRICE BEEPATH DISCLAIMER: THE ARTICLES CONTAINED IN THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE ARE NOT NECESSARILY THE OPINIONS AND/OR IDE- OLOGY OF THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE STAFF OR EDITORIAL MANAGERS OR ANY OF OUR PERSONNEL. THE ARTICLES ARE SOLELY THE IDEAS/OPINIONS/PROPERTY OF THE CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS. ALL ARTICLES AND PHOTOGRAPHS SUBMITTED A RE SUBJECTED TO EDITING AND APPROVAL. WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REFUSE SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES. NO ARTICLES, PHOTOGRAPHS OR GRAPHICS MAY BE COPIED, REPRODUCED OR STORED IN ANY TYPE OF RETRIVAL SYSTEM WITHOUT THE EXPRESS PERMISSION OF THE EDITORS OR AUTHORS. -

EJH Alliance, LLC Building Foundations for Self Reliance

EJH Alliance, LLC Building foundations for self reliance CARIBBEAN PHILANTHROPY: PAST AND POTENTIAL for The Ford Foundation Final Draft Etha J. Henry, President EJH Alliance, LLC [email protected] Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………………… 3 II. PARAMETERS AND PURPOSE ……….…………………………………………… 7 III. STUDY GOALS AND DESIGN……………………………………………………… 8 IV. CARIBBEAN CONTEXT …………………………………………………………… 9 V. FINDINGS AND OBSERVATIONS ………………………………………………… 12 VI. STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………………………. 21 VII. COMMENTARY/CONCLUSION……………………………………………………. 24 VIII. APPENDICES ………………………………………………………………………… 26 • INTERVIEW GUIDE • INDIVIDUALS INTERVIEWED • BIBLIOGRAPHY I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction “The Kalinago* determined resistance to political and cultural dominance has relevance to the people of the Caribbean today in their struggle for self determination and survival as a viable group of nations.” So states noted Scholar Beverly Steele, in her “Grenada, A History of Its People.” Participants in this study seem to validate this view. The theme of remembering and honoring history, culture and tradition as the underpinnings of Caribbean giving has reverberated throughout this Caribbean History, culture Philanthropic Tour. and traditions as underpinnings of This report represents a limited study of Caribbean Caribbean giving philanthropic giving within a subset of the English reverberated speaking Caribbean Nation States - A representative throughout the sample of The Leeward and Windward Islands: Anguilla, study tour Antigua -

Newsletter, August 2015

NN°°66 NEWSLETTER, AUGUST 2015 1 C.R.O Mission: To organise and centralise the Caribbean Rastafari Community through sustainable trade and developmen- tal programmes and activities in pursuit of our ultimate goals of reparations and repatriation. MARCUS MOSIAH GARVEY : CENTENARY OF UNIA/ TWO AMYS’ P. 3/ 6 Empress Ijahnya congratulations to King Ras FrankI non resident Ambassador of Ithiopia P.7 Guyana Rastafari Council Press Release P. 8 Yejide NjamBi Parry : Back-2-my-Roots Holistic Center P. 9/10 « The Rasta Woman » by Kathy Howell P. 11 CRO’s report on the 2nd CARICOM REPARATIONS CONFERENCE ( Oct 14/ Antigua) P.12/ 13 RASTAFARI INTERNATIONAL NEWS : The UWI MONA begin marijuana cultivation P. 14 ICAR Barbados report P.15/1 6 RASTAFARI News: Events flyers P.17/18 Pictures of St Lucia’s march for MARCUS GARVEY 2013 P.19 C.R.O’s Executive meeting report (St Lucia Sept 2013) P.20/26 Excerpts from Sir Hilary Beckles address in London P.27 Photos of CRO (Martinique, Antigua) P.28 Principles and Praxis of Reparations as David A. Comissiong P.29/ 32 CRO Contact, Membership and Donations P.33 2 MARCUS MOSIAH GARVEY Centenary of U.N.I.A Universal Negro Improvement Association As Marcus Garvey returned to Jamaica in 1914, after four years in Central America and Europe, he came upon the autobiography of Booker T. Was- hington, the conservative dean of American black leaders. It was while reading Up from Slavery, Garvey said, that he deve- loped his vision for the Universal Negro Improvement Associa- tion. -

Rastafari: Race and Resistance on a Global Scale Spring 2019 Thursdays 3

Rastafari: Race and Resistance on a Global Scale Spring 2019 Thursdays 3- Robbie Shilliam 341 - Mergenthaler [email protected] Office Hours: Thurs 11-1 and by appointment Think of Rastafari and you will probably conjure images of smiling dreadlocked musicians, draped in red, gold and green colors, spliff hanging out of mouth, greeting you with an “irie” or “one love” against a languid palm-tree backdrop. You’ll probably think of men. You’ll probably think of an over-active sexuality. If you don’t immediately conjure that image, then you’ll probably know a lot more about Rastafari than the average person. But even that knowledge will most likely be cursory, in good part because Rastafari have tended to avoid the public spotlight, oftentimes for very good reasons. However, many Rastafari now assert that it is time for a greater understanding (Rastafari would say over-standing) amongst the world’s publics. The questions are endless. For instance, is Rastafari a lifestyle, a faith, a movement? (Rastafari call it a “livity”). Is it just a Jamaican, or Caribbean thing? (The Rastafari colors are from the Ethiopian flag; many Rastafari call themselves I-thiopians). Can white people be “Rasta”? (Still somewhat of a contentious issue in some quarters; however, the Rastafari creed proclaims “death to all oppressors, black and white”). In fact, what does the word Rastafari itself mean? (Rastafari is the crown prince title of Haile Selassie I, the famous Ethiopian emperor. In the Amharic language, ras is a military title, while tafari means, “to inspire awe”). The premises of this course are that: a) Rastafari has been fundamental to pan-African struggles of the 20th century; b) Rastafari contains, by virtue of its many contending (and contentious) histories, practices and philosophies, a microcosm of Black and anti-colonial struggle on a global scale; c) Rastafari even contains a microcosm of the general struggle for global justice, and for humanity to bring “heaven on earth”. -

30 Remembering Bongo Tawney

1 “The free exchange of support and ideas is an CONTENTS essential condition to world understanding and equally to world progress." - Haile Selassie 1 PG 3 ….……………….… H.I.M SPEECH TO Wisemind e-magazine would like to thank all the people THE UN 0CT. 6TH 1963 who have helped and are helping to make this magazine PG 12 ….. OVERCOMING THE ULTIMATE a reality. CHALLENGE We would like to take this opportunity to invite ones to PG 16 ……………...……... BLACK I-STORY submit news, views & opinions, however this invitation PG 19 ……………………….. STRAIGHT UP does not guarantee immediate publication, but may be COMMUNITY BUILDING published, also depending upon available space. PG 21 ….. CONVERSATION W/ RAVIN-I PG 24 …………......... HUMP DAY - POEM ARTICLES, REASONINGS AND PG 25 …………......... KALA PANI - POEM PHOTOGRAPHS CAN BE SENT TO: [email protected] PG 26…………….…................ TRAITORS PG 27 REMEMBERING BONGO TAWNEY THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE CAN BE DOWNLOADED FREE @ TRICESBABY.COM/?P=3041 WISEMINDPUBLICATIONS.COM/NEWS COVER DESIGN: RAS RAVIN-I COVER PHOTO: ELENNA CANLAS LAYOUT: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH GRAPHIC DESIGN: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: RAS FLAKO/ IJAHNYA CHRISTIAN / JAKE HOMIAK INTERVIEWS: KATRICE BEEPATH CHIEF EDITOR – KATRICE BEEPATH TRANSCRIPTIONS: RAS FLAKO / RAS RAVIN-I DISCLAIMER: THE ARTICLES CONTAINED IN THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE ARE NOT NECESSARILY THE OPINIONS AND/OR IDE- OLOGY OF THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE STAFF OR EDITORIAL MANAGERS OR ANY OF OUR PERSONNEL. THE ARTICLES ARE SOLELY THE IDEAS/OPINIONS/PROPERTY OF THE CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS. ALL ARTICLES AND PHOTOGRAPHS SUBMITTED A RE SUBJECTED TO EDITING AND APPROVAL. WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REFUSE SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES. -

Charging the Powerhouse Sister Ijahnya Christian TRINIDAD and TOBAGO RASTAFARI UNITED NEWSPAPER

February 2006 The Peoples Newspaper #2 Above all, we must avoid the pitfalls of tribalism. If we are divided among ourselves on tribal lines, we open our doors to foreign intervention and its potentially harmful consequences. - Haile Selassie 1st Charging the Powerhouse Sister Ijahnya Christian TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO RASTAFARI UNITED NEWSPAPER IN THIS ISSUE : Page 2— ADS Page 3— Rastafari Speaks Page 4— Omega Frontline: Micaela Walker /EmpressGong Page 5— Omega Frontline : Sister Ijahnya Christian Page 6— Rasta and Politics Page 7— Rasta and Politics Page 8— Sex—Guns = Black Culture By Dr. Lance Seunarine Page 9— Sister Ijahnya Christian Page 10— Ras Jahaziel the Revelator Page 11— Ras Jahaziel the Revelator Page 12— TTRU Fundraiser Ad. @ Temple University Page 13– HIM speaks on Leadership Page 14– Empress of Zion AD for conference Page 15– Wha De People Sayin’ Page 16— In De Spotlight Cover Art— Ras Ravin-I Design and layout— Ras Ravin-I Writers— Dr. Lance Seunarine / Ras Jahaziel / Ras Ravin-I Micaela Walker / Ijahnya Christian Edited By- Ras Jahaziel— Baba Lance Seunarine— Sister Ichell Abraham / Sister Carla Johnson Photographs— Art Work Ras Ravin– I Ras Jahaziel The Return by Ras Jahaziel H.I.M Photos— TTRU Rastafari Archives E J. WESP Co., LLC All artwork are copyrighted, E Joel Wesp and is the property of Attorney at Law Ras Jahaziel and Ras Ravin-I Duplication or copying is Of Counsel to: strictly prohibited RICH, CRITES and DITTMER, LLC. © 2005 E-mail: [email protected] 300 E. Broad St, Suite 300 Columbus, Ohio, 43215– 3756 DIRECT FAX: (614) 540– 7466 PHONE: (614) 228– 5822 February 2006 The Freedom Fighter. -

The Rastafari Inethiopia: Challenges and Paradoxes of Belonging

The Rastafari inEthiopia: Challenges and Paradoxes of Belonging Mahlet Ayele Beyecha The Rastafari in Ethiopia: Challenges and Paradoxes of Belonging Master Thesis in African Studies (Research) November 2018 Mahlet Ayele Beyecha s1880225 African Studies Centre, Leiden University The Netherlands Supervisor: Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn Second supervisor: Dr. Bruce Mutsvairo Third reader: Dr. Giulia Bonacci Word count: 91,077 (excluding cover pages and references) Cover photo: A photo of Eden Genet Kawintseb. Unless noted otherwise, all photos in this thesis, including the cover photo, are copyright Mahlet Ayele Beyecha. i “Beginnings are usually scary and endings are usually sad, but it is everything in between that makes it all worth living.” King of Reggae, Robert N. Marley ii Author’s statement This research thesis has been submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the (Research) Master of Arts in African Studies. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowed without special permission provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Extended quotations from or reproduction of this manuscript, in whole or in part, are subject to permission to be granted by the copyright holder. Signed: Mahlet Ayele Beyecha iii Declaration I certify that, except where due acknowledgemnt has been made, the work is that of the author alone, and has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award. The content of this Research Master Thesis is the result of work that has been carried out since the official commencement on August 1, 2017 of the approved research program. Mahlet Ayele Beyecha November 2018 iv Acknowledgments I take this opportunity to express my profound gratitude to all the individuals whose solidarity enabled this work to be completed. -

Christian Ijahnya

%3"'5 7&34*0/ /05 50 #& $*5&% Return of the 6th Region: Rastafari Settlement in the Motherland Contributing to the African Renaissance Ijahnya Christian Caribbean Rastafari Organisation’s Liaison to the African Union Athlyi Rogers Diaspora Center Shashemane, Ethiopia In loving memory of Dame Dr. Bernice ake, QC, champion of people%s rights and freedoms 1 Introduction The purpose of university training is to produce people capable of achieving the progress and advancement of the nation People of such calibre are expected to possess deep insight, high academic discipline and intellectual zeal to crave and search for truth, to know not only the causes but also effective remedies for any ills that affect the society&to know, not only the maladies and how to expound them in vain words but also to present effective solutions and accomplish them ((IM (aile Selassie I at (aile Selassie I University, 1st ,raduation Exercises, -uly 12, 1.620 This paper presents a uni1ue opportunity for the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (C2DESRIA0, to contribute to the process of African Redemption as espoused by the Rastafari Nation in its 1uest, indeed its demand, for Repatriation to the African continent at the vanguard of the African Renaissance During his term in office, South Africa4s President Thabo Mbeki sought to popularize the African Renaissance but the rallying call for the re5birth of African pride and accomplishment seems to have diminished with Mbeki4s demit from office The Rastafari are supremely confident of their -

(With) Amy Ashwood Garvey

Theorising (with) Amy Ashwood Garvey Robbie Shilliam1 Amy Ashwood Garvey moved hundreds of thousands of people with her ideas and influence. She was an original co-conspirator, with her husband Marcus Garvey, in one of the largest and most remarkable social movements of the twentieth century: the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA). She travelled the globe, creating and sustaining networks of activists, thinkers and politicians that reached through West Africa, the Caribbean, North America and Europe. Her relentless initiatives spanned the worlds of entertainment, commerce, politics, social care, domestic economy, and publishing. She fraternised with the high and the low, the famous and the infamous. An expansive Pan-Africanism framed Amy Ashwood’s contribution to Black liberation. Moreover, that a women’s contribution could and should be made to the intellectual landscape of Black liberation was one of her core beliefs. At just seventeen years of age, Amy Ashwood publicly debated in Kingston, Jamaica, on the question: “is the intellect of woman as highly developed as that of man’s?”2 In her late 40s, towards the end of World War Two, she sought to publish an international women’s magazine “to bring together the women, especially those of the darker races, so that they may work for the betterment of all”.3 And in 1953, during the early years of the Cold War, Amy Ashwood gave a speech in Trinidad entitled “Women as Leaders of World Thought”. The speech challenged the women 1 My thanks to Empress Ijahnya Christian for a critical eye, and to Colin Prescod for confirming my approach to Amy Ashwood Garvey.