Chapter Daniel Meyer-Dinkgräfe Werktreue and Regieoper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr. 9 – 01/2019 – deutsch – english – français Wir möchten die Ortsverbände höflich bitten, zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten und Veranstaltungsankündigungen diese Links zu benutzen Link zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten für die RWVI Webseiten: http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-news/ Link zur Übermittlung von Veranstaltungshinweisen für die RWVI Webseiten. http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-event/ Danke für ihre Mithilfe. Liebe Wagnergemeinde weltweit, In den letzten zwei Jahren galt es für die Wagnergemeinde viele wichtige Geburtstage zu feiern. Nicht nur gab es Gedenktage von Birgit Nilsson und Astrid Varnay, sondern auch diejenigen einiger Mitglieder der Wagner Familie: Im Jahre 2017 Wieland Wagner (100 Jahre), im Jahre 2018 Cosima Wagner (180 Jahre), Siegfried Wagner (150 Jahre) sowie Friedelind Wagner (100 Jahre). Solche Jubiläen geben Anlass zu Rückblick und Neubetrachtungen über die Bedeutung und den Einfluss der Jubilierten für die Bayreuther Festspiele. Feierveranstaltungen zu ihren Ehren fanden unter anderem auch zweimal in Berlin statt. Im Jahre 2017 und 2018 wurde jeweils ein RWVI-Symposium durchgeführt, liebevoll organisiert vom Richard Wagner Verband Berlin-Brandenburg. Im 2019 besteht erneut Anlass zum Feiern, diesmal 100 Jahre Wolfgang Wagner. In seinem Buch „Weisst du wie es ward“ berichtet Josef Lienhart, der Ehrenpräsident des RWVI, wie Wieland Wagner schon nach der Wiedergründung des RWV (deutscher Bundesverband) im Jahr 1945 die Meinung vertrat, „dies könne letztlich nur international möglich sein“. Es hat aber bis 1991 gedauert bis der Richard Wagner Verband International (RWVI) gegründet wurde. Der RWVI hatte in den ersten Jahrzehnten mit Wolfgang Wagner als Festspielleiter zu tun. Die Internationalisierung war sehr in dessem Sinne. -

Ende Des Patriarchats Wandelt Sich Vom Riesen Fasolt in Hunding, Den Ehemann Der Einst Ge- Raubten Sieglinde

Montag, 22. August 2016 · Nr. 195 Lokales Mindener Tageblatt 3 Julia Bauer war in „Rheingold“ die Göttin Freya und singt nun Helmwige. Die Koloratur- Sopranistin verkörperte an der Komi- schen Oper Berlin die „Königin der Nacht“ in Mozarts „Zauberflöte“. Als „Arminta“ in „Die schweigsame Frau“ (Richard Strauss) erregte sie am Aalto Theater Essen Aufsehen. Julia Borchert gibt nach der Rheintochter Woglinde nun die Gerhilde. Die Sopranistin, die in Minden und Herford aufgewachsen ist, war in Palermo und Valencia als Ortlinde in der Walküre zu hören. In Bayreuth wirkte sie in der Schlingensief- Inszenierung des „Parsifal“, dirigiert von Pierre Boulez, mit. Christine Buffle verwandelt sich von der Rheintochter Wellgunde in die Walküre Ortlinde. Die Engländerin, die in Genf aufwuchs, hat ihre Karriere am Opernhaus Zürich ge- startet. Die Sopranistin hat schon mit zahlreichen namhaften Dirigenten wie Der berühmte „Ritt der Walküren“ endet in Minden in selbstbewussten Posen: Evelyn Krahe, Christine Buffle, Tiina Penttinen, Claudio Abbado, Nikolaus Harnoncourt Julia Bauer, Yvonne Berg und Dorothea Winkel (von links). MT-Foto: Ursula Koch oder Kent Nagano gearbeitet. Tijl Faveyts Ende des Patriarchats wandelt sich vom Riesen Fasolt in Hunding, den Ehemann der einst ge- raubten Sieglinde. Der Bass aus Belgien Zu den Proben zum dritten Akt der Wagner-Oper gehört zum Ensemble des Aalto Thea- ters in Essen. Dort wird er im Winter „Walküre“ ist nun das komplette Ensemble in Minden angereist. in Rigoletto und als König Marke in der Wagner-Oper „Tristan und Isolde“ Von Ursula Koch „Wir sind hier seit drei Wochen zusam- auf der Bühne stehen. men, und ich erlebe immer wieder berüh- Minden (mt). -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Das Magazin Der Nordwestdeutschen Philharmonie

INFORMATIONEN.SPIELORTE.TERMINE MAI.JUNI.JULI.AUGUST 2019 S.1 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Musikfreunde, bevor die Musikerinnen und Musiker der NWD Anfang Juli in die wohlverdiente Sommerpause starten, haben die Menschen in Ostwestfalen- Lippe noch etliche Male Gelegenheit, das Orchester in Konzerten zu erleben. Auf eine schon beachtliche Tradition können wir mit der »Klassik zu Pfingsten« zurückblicken: Seit 2002 gibt es das Pfingstfestival der NWD. Vor 17 Jahren zunächst als »Begegnung mit Beethoven« begonnen, hat es sich längst zu einer festen und nachgefragten Größe im frühsommerlichen Kulturleben unserer Region entwickelt. Ich will an dieser Stelle noch nicht zu viel verraten, doch anlässlich des 250. Geburtstages Ludwig van Beethovens wird Ihnen die NWD im nächsten Jahr wieder musikalische Begegnungen mit diesem bedeutenden Komponisten ermöglichen. Mit der »Alpensinfonie« von Richard Strauss wagt sich das Orchester nach Pfingsten an das wohl gigantischste sinfonische Werk der Musikgeschichte. Dass es gelingt, für dieses bedeutende und selten zu hörende Werk über 100 Musiker auf die Bühne zu bringen, ist einer Kooperation mit dem Ural Youth Symphony Orchestra aus dem russischen Jekaterinburg zu verdanken. Mit einem weiteren Mammutvorhaben beginnt auch die neue Konzertsaison. Zweimal wird die NWD Richard Wagners Opern-Tetralogie »Der Ring des Nibelungen« als Gemeinschaftsproduktion mit dem Richard Wagner Verband Minden und dem Stadttheater Minden aufführen. Freuen Sie sich schon jetzt mit mir auf den glanzvollen Abschluss eines auf fünf Jahre angelegten Projektes, das höchsten künstlerischen Ansprüchen gerecht wird. Ihr Andreas Kuntze/Intendant Andreas Kuntze intermezzo DAS MAGAZIN DER NORDWESTDEUTSCHEN PHILHARMONIE TIEF VERWURZELT IN DER ARMENISCHEN VOLKSMUSIK WERKE VON ARAM KHACHATURIAN ERKLINGEN BEI DER »KLASSIK ZU PFINGSTEN« Aram Khachaturian (1903–1978) Zu seinem mitreißenden Rhythmus tanzte die junge Dessen Sinfonie Nr. -

Early Opera in Spain and the New World. Chad M

World Languages and Cultures Books World Languages and Cultures 2013 Transatlantic Arias: Early Opera in Spain and the New World. Chad M. Gasta Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_books Part of the Spanish Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Gasta, Chad M., "Transatlantic Arias: Early Opera in Spain and the New World." (2013). World Languages and Cultures Books. 8. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_books/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Books by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 89_Biblioteca_Aurea.pdf 1 10/27/13 8:16 PM mploying current theories of ideology, propaganda and musical reception, Transatlantic Arias: Transatlantic Arias examines the development Eand impact of early opera in Spain and the Americas Early Opera in Spain through close examination of the New World’s first three extant operas. What emerges is an amazing and the New World C history of extraordinarily complex lyrical and musical works for their time and place, which are M also critical for illuminating inimitable perspectives Y on the cohabitation and collaboration of indigenous Transatlantic Arias Transatlantic CM groups and Europeans. MY CHAD M. GASTA is Associate Professor of Spanish and CY Chair of the Department of World Languages & 89 CMY Cultures at Iowa State University where he also serves as Director of International Studies and K Co-Director of the Languages and Cultures for Professions (LCP) program. -

Erste Tuchfühlung Mit Der Mindener Bühne Proben Zu Der Eigenproduktion „Tristan Und Isolde“ Starten / Regisseur Fordert „Pure Emotion“ Von Den Sängern

Nummer 180 · Samstag, 4. August 2012 Kultur regional Mindener Tageblatt 27 Erste Tuchfühlung mit der Mindener Bühne Proben zu der Eigenproduktion „Tristan und Isolde“ starten / Regisseur fordert „pure Emotion“ von den Sängern Von Ursula Koch Publikum als Chance und spannende Aufgabe. „Die gro- Minden (mt). „Ich möchte ße Operngestik wird hier nicht Begegnung von pure Emotion da oben. Das funktionieren“, stimmt er die Orgel und Posaune wird euch fordern. Ihr müsst sieben anwesenden Sängerin- in jeder Sekunde wissen, was nen und Sänger ein, die bis auf Lübbecke (mt). Das fünfte Ruth Maria Nicolay, die jetzt Konzert in der Veranstal- ihr tut und warum ihr es tut“, als Brangäne auftreten wird tungsreihe „Orgelsommer mahnt Matthias von Steg- und in „Lohengrin“ die Ortrud 2012“ am Sonntag, 5. Au- mann. Der Regisseur der verkörperte, noch nicht auf die- gust, um 18 Uhr in der St.- Mindener Opernproduktion ser Bühne gestanden haben. Andreas-Kirche Lübbecke, „Tristan und Isolde“ legte An die drei Sänger der bringt die Königin der Instru- den Sängern zum Probenbe- Hauptpartien Dara Hobbs mente mit einem anderen ginn seine Konzeption offen. (Isolde), Andreas Schager kraftvollen Instrument in (Tristan) und James Moellen- Verbindung: Martin Nagel Die Kompromisslosigkeit der hoff (König Marke) gewandt, und Simon Obermeier spie- von Wagner in diesem Werk formuliert von Stegmann: „Ihr len Werke für Posaune und beschriebenen Liebe will der habt die schwierigsten Partien, Orgel. Martin Nagel ist Leh- langjährige Regieassistenten aber das Haus hilft euch mit rer an der Musikschule „pro und Spielleiter bei den Bayreu- seiner Akustik auch.“ Vor al- Musica“ in Lübbecke und an ther Festspielen auf der Min- lem diese drei Darsteller for- der Kreisjugendmusikschule dener Bühne sichtbar machen. -

Minnesota Opera’S Production of La Traviata

The famous Brindisi in Minnesota Opera’s production of La Traviata. Photo by Dan Norman What can museums learn about attracting new audiences from Minnesota Opera? Summary Someone Who Speaks Their Language: How a Nontraditional Partner Brought New Audiences to Minneso- ta Opera is part of a series of case studies commissioned by The Wallace Foundation to explore arts and cultural organizations’ evidence-based efforts to reach new audiences and deepen relationships with their existing audiences. Each aspires to capture broadly applicable lessons about what works and what does not—and why—in building audiences. The American Alliance of Museums developed this overview to high- light the relevance of the case study for museums and promote cross-sector learning. The study tells the story of how one arts organization brought thousands of new visitors to its programs by partnering with an unconventional spokesperson. Minnesota Opera’s approach to reaching new audiences with messages that spoke to their interests is applicable to any museum looking to build new audiences. Challenge Like many organizations dedicated to traditional art forms, Minnesota Opera’s audience was “graying,” with patrons over sixty making up about half of its audience. While this older audience was loyal, and existing programs for young audiences showed promise, there was a gap for middle-aged people in between the ends of this spectrum. Audience Goal The Opera decided to reach out to women between the ages of thirty-five and sixty, because this demo- graphic showed unactualized potential in attendance data. They wanted to bust stereotypes that opera is a stagnant and irrelevant art form. -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

Richard-Wagner-Jahr 2013 - Auswertung

Informationsvorlage Richard Wagner Jahr 2013 - Auswertung Richard-Wagner-Jahr 2013 - Auswertung Inhalt: 1. Beschlüsse des Stadtrates / Kuratorium 1.1. RBIV-1072/07 v. 12.12.2007: Gründung des Kuratoriums „Richard-Wagner-Jahr 2013“ sowie seines Fachbeirates und des Arbeitskreises zur Vorbereitung des 200. Geburtstages von Richard Wagner im Jahr 2013 1.2. V/1172 vom 22.06.2011: Jubiläum "200. Geburtstag Richard Wagners" im Jahr 2013 1.3. Kuratorium Richard Wagner Jahre 2013 2. Eröffnung: Pressekonferenz 11. Januar 2013, Oper Leipzig 3. Beteiligte Institutionen und programmatische Höhepunkte 3.1. Oper Leipzig 3.2. Gewandhaus zu Leipzig 3.3. Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk 3.4. Der Festakt der Stadt Leipzig: 22. Mai 2013, Oper Leipzig 3.5. Universität Leipzig / Hochschule für Musik und Theater 3.6. Thomanerchor 3.7. Weitere 4. Verband, Verein, Gesellschaft, Stiftung 4.1. Richard-Wagner-Verband Leipzig 4.2. Richard-Wagner-Stiftung Leipzig 4.3. Richard-Wagner Gesellschaft 2013 e.V. 4.4. Richard-Wagner-Denkmal Verein 5. Ausstellungen 6. Presse / Marketing / wirtschaftliche & touristische Aspekte 1 Informationsvorlage Richard Wagner Jahr 2013 - Auswertung 1. Beschlüsse des Stadtrates 1.1. RBIV-1072/07 vom 12.12.2007 Gründung des Kuratoriums „Richard-Wagner-Jahr 2013“ sowie seines Fachbeirates und des Arbeitskreises zur Vorbereitung des 200. Geburtstages von Richard Wagner im Jahr 2013 1. Zur Vorbereitung des 200. Geburtstages von Richard Wagner im Jahr 2013 bildet die Stadt Leipzig ein Kuratorium „Richard-Wagner-Jahr 2013“, dem ein Fachbeirat angehört. -

Takte 1-09.Pmd

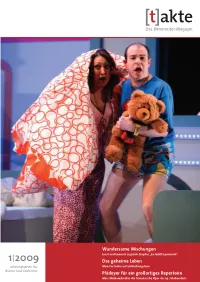

[t]akte Das Bärenreiter-Magazin Wundersame Mischungen Ernst und komisch zugleich: Haydns „La fedeltà premiata” 1I2009 Das geheime Leben Informationen für Miroslav Srnka auf Entdeckungstour Bühne und Orchester Plädoyer für ein großartiges Repertoire Marc Minkowski über die französische Oper des 19. Jahrhunderts [t]akte 481018 „Unheilvolle Aktualität“ Abendzauber Das geheime Leben Telemann in Hamburg Ján Cikkers Opernschaffen Neue Werke von Thomas Miroslav Srnka begibt sich auf Zwei geschichtsträchtige Daniel Schlee Entdeckungstour Richtung Opern in Neueditionen Die Werke des slowakischen Stimme Komponisten J n Cikker (1911– Für Konstanz, Wien und Stutt- Am Hamburger Gänsemarkt 1989) wurden diesseits und gart komponiert Thomas Miroslav Srnka ist Förderpreis- feierte Telemann mit „Der Sieg jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs Daniel Schlee drei gewichtige träger der Ernst von Siemens der Schönheit“ seinen erfolg- aufgeführt. Der 20. Todestag neue Werke: ein Klavierkon- Musikstiftung 2009. Bei der reichen Einstand, an den er bietet den Anlass zu einer neu- zert, das Ensemblestück „En- Preisverleihung im Mai wird wenig später mit seiner en Betrachtung seines um- chantement vespéral“ und eine Komposition für Blechblä- Händel-Adaption „Richardus I.“ fangreichen Opernschaffens. schließlich „Spes unica“ für ser und Schlagzeug uraufge- anknüpfen konnte. Verwickelte großes Orchester. Ein Inter- führt. Darüber hinaus arbeitet Liebesgeschichten waren view mit dem Komponisten. er an einer Kammeroper nach damals beliebt, egal ob sie im Isabel Coixets Film -

Le Temple De La Gloire

april insert 4.qxp_Layout 1 5/10/17 7:08 AM Page 15 A co-production of Cal Performances, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale, and Centre de musique baroque de Versailles Friday and Saturday, April 28 –29, 2017, 8pm Sunday, April 30, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Jean-Philippe Rameau Le Temple de la Gloire (The Temple of Glory) Opera in three acts with a prologue Libretto by Voltaire featuring Nicholas McGegan, conductor Marc Labonnette Camille Ortiz-Lafont Philippe-Nicolas Martin Gabrielle Philiponet Chantal Santon-Jeffery Artavazd Sargsyan Aaron Sheehan New York Baroque Dance Company Catherine Turocy, artistic director Brynt Beitman Caroline Copeland Carly Fox Horton Olsi Gjeci Alexis Silver Meggi Sweeney Smith Matthew Ting Andrew Trego Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale Bruce Lamott, chorale director Catherine Turocy, stage director and choreographer Scott Blake, set designer Marie Anne Chiment, costume designer Pierre Dupouey, lighting designer Sarah Edgar, assistant director Cath Brittan, production director Major support for Le Temple de la Gloire is generously provided by Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale supporters: David Low & Dominique Lahaussois, The Waverley Fund, Mark Perry & Melanie Peña, PBO’s Board of Directors, and The Bernard Osher Foundation. Cal Performances and Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale dedicate Le Temple de la Gloire to Ross E. Armstrong for his extraordinary leadership in both our organizations, his friendship, and his great passion for music. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Susan Graham Harrison and Michael A. Harrison, and Francoise Stone. Additional support made possible, in part, by Corporate Sponsor U.S. Bank. april insert 4.qxp_Layout 1 5/10/17 7:08 AM Page 16 Title page of the original 1745 libretto of Le Temple de la Gloire .