An Examination of the BSUP Scheme in the Periphery of Mumbai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

Luxury Pushes North

HINDUSTAN TIMES, MUMBAI, SATURDAY APRIL 07, 2012 htestates03 LUXURY PUSHES NORTH The skylines of towns like Kalyan and Dombivli are becoming snazzier as premium builders, such as the Tatas and Lodha Group, set up luxury housing projects there. But before you invest in a flat, check out the infrastructure Sparsh Sharma urbs, and ■ [email protected] Ambernath and Badlapur in the central ar-flung suburbs suburbs are witnessing like Dombivli, construction activity. Kalyan, Kharghar, Panvel and others The money factor are now being The main reason why home Fdeveloped by some of the seekers consider living in country’s top-notch builders. far-flung suburbs is the While some of the upcom- money factor. “As Mumbai ing projects are low-cost becomes more expensive, housing, there are ‘premium’ people have to move to housing projects coming up peripheral areas. The rate in as well. Although these the city ranges from R15,000 properties cost less to R25,000 per square foot. and other amenities compared to flats of the Even Thane is considered a need to be devel- same size and by the same mega suburb now with rates oped,” he adds. builders in the main city, ranging from R10,000 to The biggest advantage they are still considered R15,000 psf. Projects on of living in these areas is luxury projects in these Ghodbunder Road are that one can own the house. areas, and most of them priced between R8,000 and Ram Makhecha, director of boast modern amenities. R10,000, while the rate in Vakratunda Group, says, Some of these projects CBD Belapur is between “With nuclear families and include Amantra by Tata R7,000 and R8,000,” says people in their early 30s Housing on the Mumbai- Bharat Malik, a realtor. -

The Development of Kalyan Dombivili; Fringe City in a Metropolitan Region

CITY REPORT 2 JULY 2013 The Development of Kalyan Dombivili; Fringe City in a Metropolitan Region By Isa Baud, Karin Pfeffer, Tara van Dijk, Neeraj Mishra, Christine Richter, Berenice Bon, N. Sridharan, Vidya Sagar Pancholi and Tara Saharan 1.0. General Introduction: Framing the Context . 3 Table of Contents 8. Introduction: Context of Urban Governance in the City Concerned . 3 1. Introduction: Context of Urban Governance in the City Concerned . 3 1.1. Levels of Government and Territorial Jurisdictions in the City Region . 7 1.0. General Introduction: Framing the Context . 3 1.1. Levels of Government and Territorial Jurisdictions Involved in the City Region: National/Sectoral, Macro-Regional (Territory), Metropolitan, Provincial and Districts . 7 9. Urban Growth Strategies – The Role of Mega-Projects . 10 2. Urban Growth Strategies – The Role of Mega-Projects . 10 2.1. KDMC’s Urban Economy and City Vision: 2.1. KDMC’s Urban Economy and City Vision: Fringe City in the Mumbai Agglomeration . 10 Fringe City in the Mumbai Agglomeration . 10 3.1. Urban Formations; 3. Addressing Urban Inequality: Focus on Sub-Standard Settlements . 15 Socio-Spatial Segregation, Housing and Settlement Policies . 15 3.1. Urban Formations; Socio-Spatial Segregation, Implications for Housing and Settlement Policies . 15 3.2. Social Mobilization and Participation . 20 10. Addressing Urban Inequality: . 15 3.3. Anti-Poverty Programmes in Kalyan Dombivili . 22 11. Focus on Sub-Standard Settlements9 . 15 4. Water Governance and Water-Related Vulnerabilities . 26 4.1. Water Governance . 26 3.2. Social Mobilization and Participation . 20 4.2. Producing Spatial Analyses of Water-Related Risks and Vulnerabilities: 3.3. -

M/S M/S Exotic Bites

+91-8048372558 M/s M/s Exotic Bites https://www.indiamart.com/m-s-m-s-exotic-bites/ Incepted in the year 2015, Exotic Bites is amongst the foremost names, indulged in Wholesaling and Trading an extensive range of Green Peas, Fresh Paneer and many more. About Us Incepted in the year 2015, Exotic Bites is amongst the foremost names, indulged in Wholesaling and Trading an extensive range of Green Peas, Fresh Paneer and many more. The offered products are widely employed by customers for various purposes. These products are processed under the rigorous leadership of highly proficient experts using the optimum grade ingredient and advanced technology. These products are extremely used in the market for their longer shelf life, purity and nominal prices. Furthermore, the presented products are available in many forms as per the exact necessities of customers. In order to provide excellent quality of products to patrons, we have hired skilled and experienced team. Our team ensures that the products are delivered to patrons in within given time frame keeping the quality. Moreover, we work under the direction of our mentor Mr. Keval Damani (Partner). Under his direction we have attained a well-known place of this area. He has always motivated us to provide the best quality products to our customers. We provide our products in following locations: Thane, airoli, sanpada, turbhe, vashi, koparkarine, panvel, gansoli, midc, juinagar,nerul, seawood darave, CBD belapur, kharghar, manasarovar, khandeshwar,kalva diva ,kopar,dombivali,thakurli, kalyan vithalwadi. ulhasnagar,ambernath, badlapur, vangani, shelu, neral bhivpuri rd, karjat palasdhari, khopoli ambivli,titwala, khadavli,.. -

19. Final-Sitewise Mercury Level- Final Reference Checked

J.S Menon and OurS.V. Nature Mahajan (2010) / Our 8:170-179 Nature (2010) 8: 170-179 Site-wise Mercury Levels in Ulhas River Estuary and Thane Creek near Mumbai, India and its Relation to Water Parameters * J.S. Menon and S.V. Mahajan B.N. Bandodkar College of Science, Chendani-Koliwada, Thane (West), Mumbai-400601, India *E-mail: [email protected] Received: 11.06.2010, Accepted: 20.10.2010 Abstract Ulhas river estuary (73°14 ′E, 19°14 ′N to 72°54 ′E, 19°17 ′N) and Thane creek (72°55 ′E, 19°N to 73°E, 19°15 ′N) near Mumbai, India are highly polluted owing to the heavy load of industrial pollutants and sewage discharge. The traditional fisher-folk living along the banks of Ulhas river estuary and Thane Creek rely on these contaminated fish for their daily sustenance, thereby being exposed to heavy mercury pollution for several years. However, little attention has been given to the levels of mercury in water, its intake and exposure to those populations. In the present study, mercury levels in the waters of Ulhas river estuary and Thane creek has been analysed and its relation with other physico- chemical parameters have been studied. Mercury level was maximum in Wehele station and Alimgarh station with an average of 8.57 ng/ml and minimum at Diwe-Kewni station with 2.6 ng/ml. Vittawa and Airoli stations along Thane creek showed moderate levels with an average of 5.71 ng/ml. The reference site, Khadavli had Hg below the level of detection in the water samples. -

Godrej Upavan Location Docket

GODREJ UPAVAN THANE EXTENSION Thane Extensionwelcomes you to the future. Stock image for representation purpose only. Stock image for representation The project is registered as Godrej Upavan under MahaRERA No. P51700027436 available at http://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in. The project is being developed by “Prakhhyat Dwellings LLP” in which Godrej Properties Limited is a partner. The sale is subject to terms of the Application Form and the Agreement, including specication. All specications of the unit shall be as per the nal agreement between the Parties. Recipients are advised to apprise themselves of the necessary and relevant information of the project / offer prior to making any purchase decisions. The ofcial website of Godrej Properties Ltd. is www.godrejproperties.com. Please do not rely on the information provided on any other website. The upcoming infrastructure facilities mentioned in this document are proposed to be developed by the Government and other authorities and we cannot predict the timing or the actual provisioning of the facilities, as the same is beyond our control. We shall not be responsible or liable for any delay or non-provisioning of the same. Mumbai plans its future at Thane Extension purpose only. Stock image for representation Welcome to Godrej Upavan, a home located at Thane Extension that is only a 20-minute** drive time from the Majiwada Circle. You will nd 20-minute yourself at a location where Mumbai drive time** from Thane Majiwada is planning its future. It ticks all the Circle. boxes of a good real estate hub-accessibility, infrastructure and quality of life. Thane Extension offers easy connectivity to major business centres and the ease of access to various major cities and towns.* It is slowly becoming one of the biggest attractions for home-buyers. -

Download Brochure

THE BIRTH OF PROGRESSIVE HOUSING. INDIA’S LARGEST AND MOST UNIQUE PROGRESSIVE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT AT THE NEXT GROWTH CENTRE OF MUMBAI: KALYANAMBIVLI. # Ramrajya main roundabout# Ramrajya main roundabout KALYANAMBIVLI. THE NEXT GROWTH CENTRE OF MUMBAI. A handpicked location, making this development Mumbai’s only mega project just 5 minutes from station. An incredible combination of a strategic location, social infrastructure & 6-mega projects that will transform Kalyan-Ambivli. MUMBAI’S ONLY MEGA PROJECT, 5 MINUTES FROM A STATION. To Harbour RAMRAJYA Fort, To Navi Mumbai BKC Nariman Point Ambivli Kalyan Thane Ghatkopar Kurla Dadar CST 5 mins 10 mins 25 mins 45 mins 50 mins 60 mins 75 mins Bhiwandi, Metro to West To Western Ulhasnagar Powai via Kanjurmarg Lower Parel, Elphinstone • Direct connectivity on the Central railway line with the largest commercial centres of the region: reach Kalyan in 10 mins, Thane in 25 mins and less than 1 hour to Dadar, Gharkopar and Kurla* • Connectivity to the important sectors of Navi Mumbai via the Trans-Harbour Line between Thane and Vashi • Connectivity to the important industrial and commercial belts of Bhiwandi, Ulhasnagar, Ambernath, Badlapur and Titwala • Road connectivity to Kalyan and Titwala, which, in turn, connects you to all of Mumbai • Easy access to public transport systems: KDMT bus service, NMMT bus service and TMT Bus Service 6 MEGA PROJECTS FOR PROGRESS. 6 significant infrastructure projects, coming up soon around this development, are destined to put growth and progress here on fast track. -

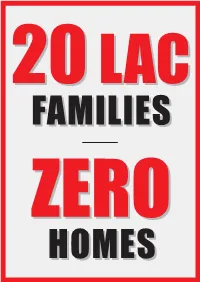

Location Document 04-04-2018 UN 05

2020 LACLAC FAMILIESFAMILIES ZEROZERO HOMESHOMES INDIA'SINDIA'S PROGRESSIVEPROGRESSIVE BIGGESTBIGGEST HOMESHOMES PROGRESSIVEPROGRESSIVE ATAT MUMBAI’SMUMBAI’S NEXTNEXT HOUSINGHOUSING GROWTHGROWTH ALLOTMENTALLOTMENT CENTRE,CENTRE, SCHEMESCHEME KALYAN-AMBIVLIKALYAN-AMBIVLI BEBE THETHE FIRSTFIRST TOTO BEATBEAT THETHE QUEUEQUEUE INTRODUCING NOT JUST HOMES BUT A NEW WAY OF LIVING PROGRESSIVE HOMES FORPROGRESSIVEMUMBAIKARS A STRATEGIC LOCATION SET TO BECOME MUMBAI’S NEXT GROWTH CENTRE MUMBAI’S ONLY MEGA-PROJECT JUST 5 MINUTES FROM A STATION 6 MEGA PROJECTS SET TO RADICALLY TRANSFORM KALYAN-AMBIVLI To Harbour Fort, To Navi Mumbai BKC Nariman Point The Next Central Business District MMRDA to develop 330 hectares with the Mumbai University South Korean Government Ambivili Kalyan Thane Ghatkopar Kurla Dadar CST New campus to start courses after 5 mins 10 mins 25 mins 45 mins 50 mins 60 mins 75 mins Diwali this year Bhiwandi, Metro to West To Western Ulhasnagar Metros to Thane & Navi Mumbai Powai via Kanjurmarg Lower Parel, Elphinstone Thane-Bhiwandi- Kalyan Metro by 2019 & Ring Road planned by MMRDA work to start for Kalyan-Taloja in 2018 29 km ring road passing through the development, connecting parts ▶ Direct connectivity by central line with the largest commercial centres of the region: of KDMC Kalyan in 10 mins, Thane in 25 mins and Ghatkopar, Kurla & Dadar within an hour^ 126km Virar-Alibaug ▶ Connected to major parts of Navi Mumbai via trans-harbor line between Thane & Vashi multi-modal corridor Phase 1 to complete by March 2022 Ferry services -

Best Practices 2019-2020

BEST PRACTICES 2019-2020 7.2 Best Practices Best Practice 1 Title of Practice: - ‘Each One Teach One’ Objectives 1. Assist teachers in strengthening the educational standards of KDMC School No.70 2. Arouse interest for learning among school students and to attend their school regularly. 3. Involve students in the learning process through book reading and other exercises. The Context One of the missions of our college is ‘To act as a catalyst in empowering learners to become better citizens by developing a sense of social conscience and commitment’. Under this mission, our College under NSS has adopted KDMC School Number 70 situated at Kanchangaon, Thakurli (E). The objective of this practise is to help the KDMC School students in their daily education. This school has nearly 71 students, mostly comprising of underprivileged family and first generation learners. The Practice In continuation of ‘Each One Teach One’ program, it was decided to help the KDMC No. 70 situated at Kanchangaon, Thakurli, to attract new students and retain existing strength. Students of our college visited the school on rotational basis to help the school teachers to teach students from 1st to 7th Stds. Interesting and interactive methods like showing educational videos, playing games related to identification of Marathi and English alphabets and puzzles along with songs and poems from the curriculum were undertaken to enliven the class and draw students to attend school regularly. Our students also created awareness about the importance of cleanliness and personal hygiene. The college donated badminton rackets, carom board and puzzle sets. For setting up a mini library, we donated story books, academic books and a wooden cupboard. -

Godrej Upavan Mini Booklet

GODREJ UPAVAN THANE EXTENSION The of more The project is registered as Godrej Upavan under MahaRERA No. P51700027436 available at http://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in. The project is being developed by “Prakhhyat Dwellings LLP” in which Godrej Properties Limited is a partner. The upcoming infrastructure facilities mentioned here are proposed to be developed by the Government and other authorities and we cannot predict the timing or the actual provisioning of the facilities, as the same is beyond our control. We shall not be responsible or Stock image for representation purpose only. Stock image for representation liable for any delay or non-provisioning of the same. Welcometo Thane Extension. It’s where Mumbai is planning its future. Welcome to Godrej Upavan, a home located at Thane Extension that is only a 20-minute 20-minute** drive time from the Majiwada drive time** from Circle. You will nd yourself at a location Thane Majiwada where Mumbai is planning its future. It Circle. ticks all the boxes of a good real estate hub-accessibility, infrastructure and quality of life. Thane Extension offers easy connectivity to major business centres and the ease of access to various major cities and towns.* It is slowly becoming one of the biggest attractions for home-buyers. The central location of Thane-Kalyan-Ambivali now opens its arms to Godrej Upavan, a home that gives you more. Stock image for representation purpose only. Stock image for representation *https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/thane-real-estateamong-top-20-in-the-world-where-rich-want- to-invest-survey/story-efXxd1kGc0gjgV0hcL6iPI.html **Drive time refers to the time taken to travel by a car basis normal trafc conditions during non-peak hour as per Google maps. -

Opp Doc Final

The project is registered as Godrej Nirvaan underMahaRERA No.P51700022148 available athttp://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in. asGodrej isregistered The project Stock image for representative purpose only The Thane Extension. The rising destination Evolution of tomorrow. Story Just 20 minutes** to the busy Majiwada Circle and the green stretches of Ghodbunder Road, Thane is planning its future. The location is a growing real estate hub basis its accessibility, infrastructure and quality of life. The central location of Kalyan-Ambivli in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region together with its connectivity to major business centres and the ease of MUMBAI THANE WHAT’S access to various major cities EXPLORED EXPLORED NEXT and towns are some of the biggest The commercial Among world's capital of India, top 20 real estate attractions for home buyers. outlined by the investment destinations Bandra Worli according to a recent Sea Link study by Knight Frank, International Property ? Consultant* *https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/thane-real-estate- among-top-20-in-the-world-where-rich-want-to-invest-survey/ story-efXxd1kGc0gjgV0hcL6iPI.html **Source: Google Maps. Travel time basis normal traffic conditions. Source:- Liases Foras APARTMENTS BOUGHT 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 FY 12-13 FY 13-14 FY 14-15 FY 15-16 FY 16-17 FY 17-18 FY 18-19 THANE THANE EXTENSION On only purpose representative for image Stock the rise. Over last 6 years percentage growth in apartments bought in Thane has been 88%, while for Thane Extension it has been 232% Thane extension has retained a Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of greater than 20% in the past 5 years. -

Kasara-Khopoli-Karjat

KASARA-KHOPOLI-KARJAT-KALYAN-THANE-MUMBAI CST KASARA-KHOPOLI-KARJAT-KALYAN-THANE-MUMBAI CST Stations 96002 96102 97302 97304 97602 96302 97306 96602 Stations 96304 95902 96104 97002 97604 97308 96604 97606 SKP 2 S 2 T 2 T 4 C 2 A 2 T 6 TL 2 A 4 T 8 S 4 K 2 C 4 T 10 TL 4 C 6 X X Kasara Kasara Khardi Khardi Atgaon Atgaon Asangaon Asangaon Vasind Vasind Khadavli Khadavli Titwala 04:01 Titwala 04:37 Ambivli 04:09 Ambivli 04:45 Shahad 04:12 Shahad 04:48 Khopoli 00:30 Khopoli Lowjee 00:34 Lowjee Dolavli 00:38 Dolavli Kelavli 00:41 Kelavli Palasdhari 00:48 Palasdhari Karjat 00:55 02:35 Karjat 03:41 Bhivpuri Road 02:44 Bhivpuri Road 03:50 Neral 02:51 Neral 03:57 Shelu 02:55 Shelu 04:01 Vangani 02:59 Vangani 04:05 Badlapur 03:08 Badlapur 04:14 Ambernath 03:15 03:45 Ambernath 04:11 04:21 Ulhas Nagar 03:19 03:51 Ulhas Nagar 04:17 04:25 Vithalwadi 03:21 03:53 Vithalwadi 04:19 04:27 Kalyan 03:26 03:59 04:17 Kalyan 04:24 04:33 04:41 04:53 Thakurli 03:32 04:04 04:22 Thakurli 04:30 04:38 04:46 04:58 Dombivli 03:36 04:07 04:25 Dombivli 04:33 04:41 04:49 05:01 Kopar 03:40 04:10 04:28 Kopar 04:36 04:44 04:52 05:04 Diva 03:44 04:15 04:33 Diva 04:41 04:49 04:57 05:09 Mumbra 03:50 04:19 04:37 Mumbra 04:45 04:53 05:01 05:13 Kalva 03:56 04:25 04:43 Kalva 04:51 04:59 05:07 05:19 Thane 04:01 04:05 04:19 04:29 04:39 04:47 Thane 04:55 05:08 05:03 05:11 05:19 05:23 Mulund 04:06 04:10 04:24 04:34 04:44 04:52 Mulund 05:00 05:13 05:08 05:16 05:24 05:28 Nahur 04:09 04:13 04:27 04:37 04:47 04:55 Nahur 05:03 ..