Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to the Puritans: Memorial Edition

Introduction to the Puritans Memorial Edition Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) INTRODUCTION TO THE PURITANS Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) Memorial Edition A Tribute to the Life and Ministry of Erroll Hulse Dedicated to the memory of Erroll Hulse with great joy and gratitude for his life and ministry. Many around the world will continue to benefit for many years to come from his untiring service. Those who knew him, and those who read this volume, will be blessed by his Christ- honoring life, a life well-lived to the glory of God. The following Scripture verses, psalm, and hymns were among his favorites. ISAIAH 11:9 They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. HABAKKUK 2:14 For the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. PSALM 72 1Give the king thy judgments, O God, and thy righteousness unto the king’s son. 2He shall judge thy people with righteousness, and thy poor with judgment. 3The mountains shall bring peace to the people, and the little hills, by righteousness. 4He shall judge the poor of the people, he shall save the children of the needy, and shall break in pieces the oppressor. 5They shall fear thee as long as the sun and moon endure, throughout all generations. 6He shall come down like rain upon the mown grass: as showers that water the earth. 7In his days shall the righteous flourish; and abundance of peace so long as the moon endureth. -

The Glass No. 11, Winter 1998

THE GLASS THE GLASS NUMBER 11 WINTER 1998 Editorial 2 ‘Mercie, mercie to crye and crye again’: repentance and resolution in Anne Lock’s Meditation of a Penitent Sinner Jill Seal 3 Escape to Wallaby Wood: C S Lewis’s Depictions of Conversion Michael Ward 16 Old Western Man for Our Times: C S Lewis’s Literary Criticism Stephen Logan 33 From Pillar to Post: A Response to David Tomlinson’s The Post- Evangelical Kevin Mills 50 Reviews 58 Notes on Contributors 62 News and Notes 63 Published by the Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship (UCCF) for the Literary Studies Group. UCCF 38 De Montfort Street Leicester LE1 7GP Tel 0116 255 1700 www.uccf.org.uk [email protected] © The contributors 1998 ISSN 0269-770X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any1 form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. The views of the contributors do not necessarily reflect editorial stance. UCCF holds personal details on computer for the purpose of mailing in accordance with terms registered under the Data Protection Act 1984 – details available on request. THE GLASS Editorial Even those who have done courses in 16th century English literature may not be familiar with the name of Anne Lock, yet she is the poetic creator of a remarkable sonnet cycle based on Psalm 51, the psalm of Davidic repentance. Anne Lock was in fact a pioneer of the sonnet form, and her opus, presented in this issue by Jill Seal − whose research may also be fairly described as pioneering − is the earliest known sonnet sequence in English. -

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner and the Problem of Ascription

This is a pre-publication draft of this article and should not be used for citation purposes. Deirdre Serjeantson [email protected] Anne Lock’s anonymous friend: A meditation of a penitent sinner and the problem of ascription Christopher Goodman lived most of his adult life on the wrong side of prevailing orthodoxies. At the accession of Queen Mary, Goodman was the Lady Margaret professor of divinity at Oxford: finding himself out of sympathy with the state’s reversion to Catholicism, he went into exile on the continent. He joined his English co-religionists at Frankfurt in 1554, but when the congregation quarrelled over the use of the 1552 Prayer Book, Goodman was one of the faction which could not be reconciled, and he left for Calvin’s Geneva in 1555. In that more congenial atmosphere he wrote his 1558 treatise, How superior powers ought to be obeyed , which, like John Knox’s notorious First blast of the trumpet against the monstrous regiment of women (1558), argued against the legitimacy of female monarchs. The books were primarily motivated by their opposition to the rule of Queen Mary, who was disqualified, they argued, for reasons of religion as well as gender. Their comments were ill- timed, coinciding as they did with Mary’s death and the coronation of another queen. For all that Goodman had praised her – a ‘Godlie Lady, a[n]d meke Lambe, voyde of all Spanishe pride, and strange bloude’ (Mary, by contrast, was an ‘vngodlie serpent’) – Elizabeth took a dim view of both books. 1 Her religious views may have been more acceptable to the authors, but their attack on female monarchy appears to have gravely offended her: in June 1559, William Cecil, writing from the Court, reported that ‘Of all others, Knoxees name, if it be not Goodmans, is most odiose here.’ 2 Prudently, both men established themselves in Scotland on their return from Geneva; however, when the earl of Moray’s rebellion in 1565 forced Goodman to seek office in territories controlled by Elizabeth, he was to find his advancement implacably blocked. -

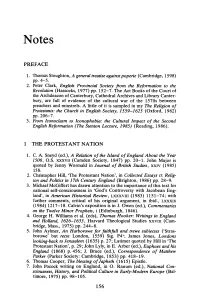

Preface 1 the Protestant Nation

Notes PREFACE 1. Thomas Stoughton, A general treatise against poperie (Cambridge, 1598) pp.4-5. 2. Peter Clark, English Provincial Society from the Reformation to the Revolution (Hassocks, 1977) pp. 152-7. The Act Books of the Court of the Archdeacon of Canterbury, Cathedral Archives and Library Canter bury, are full of evidence of the cultural war of the 1570s between preachers and minstrels. A little of it is sampled in my The Religion of Protestants: the Church in English Society, 1559-1625 (Oxford, 1982) pp.206-7. 3. From Iconoclasm to Iconophobia: the Cultural Impact of the Second English Reformation (The Stenton Lecture, 1985) (Reading, 1986). 1 THE PROTESTANT NATION 1. C. A. Sneyd (ed.), A Relation of the Island of England About the Year 1500, O.S. XXXVII (Camden Society, 1847) pp. 20-1. John Major is quoted by Jenny Wormald in Journal of British Studies, XXIV (1985) 158. 2. Christopher Hill, 'The Protestant Nation', in Collected Essays II: Relig ion and Politics in 17th Century England (Brighton, 1986) pp. 28-9. 3. Michael McGiffert has drawn attention to the importance of this text for national self-consciousness in 'God's Controversy with Jacobean Eng land', in American Historical Review, LXXXVIII (1983) 1151-74; with further comments, critical of his original argument, in ibid., LXXXIX (1984) 1217-18. Calvin's exposition is in J. Owen (ed.), Commentaries on the Twelve Minor Prophets, I (Edinburgh, 1846). 4. George H. Williams et al. (eds), Thomas Hooker: Writings in England and Holland, 1626-1633, Harvard Theological Studies XXVIII (Cam bridge, Mass., 1975) pp. -

Religion for Further Reading

1 Chapter Six: Religion For Further Reading Wide-ranging collections of articles provide a good place to begin if you wish an overview of women’s role in religion. Some of the best include Rosemary Radford Ruether, Religion and Sexism: Images of Woman in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1974); Rosemary Radford Ruether and Eleanore McLaughlin (eds.), Women of Spirit: Female Leadership in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1979); Richard L. Greaves (ed.), Triumph Over Silence: Women in Protestant History (Westport, CT, Greenwood, 1985); Lynda L. Coon et al. (eds.), That Gentle Strength: Historical Perspectives on Women in Christianity (Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1990); W. J. Shields and Diana Wood (eds.), Women in the Church, Studies in Church History, vol. 27 (Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990); Judith Baskin (ed.), Jewish Women in Historical Perspective (Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1991); Kari Elizabeth Borreson and Kari Vogt (eds.), Women’s Studies of the Christian and Islamic Traditions: Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Foremothers (Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic, 1993); Daniel Bornstein and Roberto Rusconi (eds.), Women and Religion in Medieval and Renaissance Italy (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1996); Beverly Mayne Kienzle and Pamela J. Walker (eds.), Women Preachers and Prophets through Two Millennia of Christianity (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998). 2 Two collections focus only on the early modern period, with articles about women in many countries, are Sherrin Marshall (ed.), Women in Reformation and Counter- Reformation Europe: Public and Private Worlds (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1989), and Susan E. Dinan and Debra Meyers (eds.), Women and Religion in Old and New Worlds (New York, Routledge, 2001). -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 J. Mush, An Abstracte of the Life and Martirdome of Mistres Margaret Clitherow (Mechelen, 1619), sig. A2±A2v. 2 Troubles of Our Catholic Forefathers Related by Themselves, ed. J. Morris (London, 1877), vol. 3, p. 432; The Chronicle of the English Augustinian Canonesses Regular of the Lateran, at St Monica's in Louvain (now at St Augustine's Priory, Newton Abbot, Devon) 1548±1644, ed. A. Hamilton, hereafter Chronicle of St Monica's (London, 1904), vol. 1, pp. 33±4. 3 Chronicle of St Monica's, vol. 1, pp. 16±17, 33, 46±55, 80±4, 175±9, 189±90, 205±6; vol. 2, pp. 164±8. 4 H. Peters, Mary Ward: A World In Contemplation, trans. H. Butterfield (Leomin- ster, 1994); J. Cameron, A Dangerous Innovator: Mary Ward 1585±1645 (Sydney, 2000); M. Wright, Mary Ward's Institute: The Struggle for Identity (Sydney, 1997); P. Guilday, The English Catholic Refugees on the Continent 1558±1795 (London, 1914), pp. 163±214; St Mary's Convent, Micklegate Bar, York (1686±1887), ed. H. J. Coleridge (London, 1887). 5 Their publications on the history and archives of convents and individuals are too numerous to list, but the principal journals include: Recusant History; Downside Review; Ampleforth Journal; Essex Recusant; London Recusant; Northern Catholic History; Staffordshire Catholic History; Catholic Archives. See also the CRS records and monographs series. The two standard studies of the convents abroad are Guilday, Catholic Refugees; and B. Whelan, Historic English Convents of Today: The Story of the English Cloisters in France and Flanders in Penal Times (London, 1936). -

The Role of Women in the English Reformation Illustrated by the Life and Friendships of Anne Locke

The Role of Women in the English Reformation illustrated by the Life and Friendships of Anne Locke PATRICK COLLINSON Lecturer in Ecclesiastical History, Kings College, University of London HE notable part played by women in the Reformation has rarely been given its due recognition in English historical T studies. In recent years Professor Wallace Notestein has written with characteristic authority and grace on 'The English Woman, 1580-1650,'x but one does not learn from this essay that the English women of this age had any religious propensities at all. And leaving aside the more prominent figures such as Queen Catherine Parr, Lady Jane Grey, and Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk, women make but few appearances in most accounts of the English Reformation. This is no doubt only one symptom of the tendency of so many of our histories to dwell upon the officially inspired aspects of the Reformation to the neglect of the spontaneous and the local; to be concerned with the making of settlements and their enforce ment rather than with the means by which Protestantism actually spread in families, towns, and other communities. And of course there are special factors which obscure the female contribution to history, the legal disabilities of the sex, which so often hide the married woman and allow us to catch glimpses only of the widow, a 'person' in law. Yet in France, where by the nature of the case a more sensitive historical criticism has had to be directed towards what Americans might call the grass-roots of Protestantism, the supreme importance of women in its propagation has not been missed. -

Bloomfield, the Poetry of Interpretation

The Poetry of Interpretation: Exegetical Lyric after the English Reformation Gabriel Bloomfield Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Gabriel Bloomfield All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Poetry of Interpretation: Exegetical Lyric after the English Reformation Gabriel Bloomfield “The Poetry of Interpretation” writes a pre-history of the twentieth-century phenomenon of close reading by interpreting the devotional poetry of the English Renaissance in the context of the period’s exegetical literatures. The chapters explore a range of hermeneutic methods that allowed preachers and commentators, writing in the wake of the Reformation’s turn to the “literal sense” of scripture, to grapple with and clarify the bible’s “darke texts.” I argue that early modern religious poets—principally Anne Lock, John Donne, George Herbert, William Alabaster, and John Milton—absorbed these same methods into their compositional practices, merging the arts of poesis and exegesis. Consistently skeptical about the very project they undertake, however, these poets became not just practitioners but theorists of interpretive method. Situated at the intersection of religious history, hermeneutics, and poetics, this study develops a new understanding of lyric’s formal operations while intimating an alternative history of the discipline of literary criticism. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgments iii Note on Texts vi Introduction 1 1. Expolition: Anne Lock and the Poetics of Marginal Increase 33 2. Chopology: How the Poem Crumbles 87 3. Similitude: “Multiplied Visions” and the Experience of Homiletic Verse 147 4. Prosopopoeia: The Poem’s Split Personality 208 Bibliography 273 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. -

The Case of John Knox

Quidditas Volume 6 Article 12 1985 Correspondence with Women: The Case of John Knox A. Daniel Frankforter Pennsylvania State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frankforter, A. Daniel (1985) "Correspondence with Women: The Case of John Knox," Quidditas: Vol. 6 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol6/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Correspondence with Women: The Case of John Knox by A. Daniel Frankforter Pennsylvania State University The Reformaiion opened an ambiguous era for women. There were risk of losses and opportunities for gain for women who made the transition 10 Protestant faith. Protestant women gave up some traditional religiou sup ports. The Virgin Mary and the female saints, who provided Catholic women with role models and isterly patronage, were thrust aside.' Priestly interces sion ended, and Protestant women, like men, stood alone with their consciences in the presence of God. Women were denied the option of career as nuns in self governing female communities, and virginity ceased to be a respected female vocation. All women were expected to marry, and both church and state ordered them to ubmit to the "spiritual control of their spouse ."' There was promi e, however, in the fact that the Reformation accorded marriage the dignity of a spiritual vocation.l Sexuality was given greater respect.• Mothers were recognized as having responsibility for the spiritual nurture of their children. -

Women's Participation in the Early Scottish Presbyterian Church

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 The Female Kirk: Women's Participation in the Early Scottish Presbyterian Church Lydia Mackey College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Mackey, Lydia, "The Female Kirk: Women's Participation in the Early Scottish Presbyterian Church" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1647. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1647 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Female Kirk: Women’s Participation in the Early Scottish Presbyterian Church A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History from The College of William and Mary by Lydia Jane Mackey Accepted for __Highest Honors___________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) Nicholas Popper__________________________ Professor Nicholas Popper, Director Simon Middleton_______________________ Professor Simon Middleton Catherine Levesque________________________ Professor Catherine Levesque Williamsburg, VA May 10, 2021 Mackey 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 2 Map . 3 Introduction . 4 Chapter 1: From Advising to Rioting: Women’s Involvement in the Wider Community . .16 Chapter 2: Women’s Writing: Ministering from the Page . 39 Chapter 3: Independence and Influence in the Private Sphere. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Lady Anne Bacon (c.1528–1610) was a woman who inspired strong emotion in her own lifetime. As a girl, she was praised as a ‘verteouse meyden’ for her religious translations, while a rejected suitor condemned her as faithless as an ancient Greek temptress.1 The Spanish ambassador reported home that, as a married woman, she was a tiresomely learned lady, whereas her husband celebrated the time they spent reading classical literature together.2 During her widowhood, she was ‘beloved’ of the godly preachers surrounding her in Hertfordshire; Godfrey Goodman, later bishop of Gloucester, instead argued that she was ‘little better than frantic in her age’.3 Anne’s own letters allow a more balanced exploration of her life. An unusually large number are still extant; she is one of the select group of Elizabethan women whose surviving correspondence includes over fifty of the letters they wrote themselves, a group that incorporates her sister, Lady Elizabeth Russell, and the noblewoman Bess of Hardwick, the countess of Shrewsbury.4 1G.B., ‘To the Christen Reader’, in B. Ochino, Fouretene sermons of Barnadine Ochyne, concernyng the predestinacion and eleccion of god, trans. A[nne] C[ooke] (London, 1551), sig. A2r. For Walter Haddon’s comparison of Anne to Cressida, a character from ancient Greek mythology, see BL, Lansdowne MS 98,fo.252r. 2M.A.S. Hume (ed.), Calendar of Letters and State Papers Relating to English Affairs Preserved Principally in the Archives of Simancas, 1558–1603, 4 vols (1892–1899), I, p. 20;N.Bacon,The Recreations of His Age (Oxford, 1919), p. -

Copyright by Noël Clare Radley 2013 Some Rights Reserved

Copyright by Noël Clare Radley 2013 Some Rights Reserved (see Appendix A) The Dissertation Committee for Noël Clare Radley certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Embodied Mind & Sixteenth-Century Poetry: Wyatt, Vaughan Lock, & Shakespeare Committee: ______________________________________ Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski, Supervisor ______________________________________ Kurt Heinzelman ______________________________________ Jason Powell ______________________________________ Coleman Hutchison ______________________________________ John Rumrich Embodied Mind & Sixteenth-Century Poetry: Wyatt, Vaughan Lock, & Shakespeare by Noël Clare Radley, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication To Karen Wiener International Advocate for Literacy, Scholar, Friend “Just like moons and like suns, With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high, Still I’ll rise.” —Maya Angelou Acknowledgements There are many people to thank, including friends, faculty, and staff in the Department of English and the Department of Rhetoric and Writing. I would like to thank my committee, including Jason Powell of St. Joseph’s University, Coleman Hutchison, and John Rumrich. I would like to thank Kurt Heinzelman, who directed my work during an earlier part of the project. I would especially like to thank the chair of my committee, Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski, who mentored and inspired me during a time of vital productivity. I cannot imagine how I could have completed the project without her gifts of time, energy, enthusiasm, and insight. To my parents, my sisters, my brother, and extended family, you have cared for me beyond words: thank you.