ENG 8001 Syllabus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Lady of the Merchant of Venice

3 The dark lady of The Merchant of Venice ‘The Sonnets of Shakespeare offer us the greatest puzzle in the history of English literature.’ So began the voyage of Alfred Leslie Rowse (1903–97) through the murky waters cloaking the identi- ties of four persons associated with the publication in 1609 of Shakespeare’s ‘sugared sonnets’: the enigmatic ‘Mr. W.H.’ cited in the forepages as ‘onlie begetter’ of the poems; the unnamed ‘fair youth’ addressed in sonnets 1–126; the ‘rival poet’ who surfaces and submerges in sonnets 78–86; and the mysterious ‘dark lady’ celebrated and castigated in sonnets 127–52.1 Doubtless, even as Thomas Thorpe’s edition was passing through George Eld’s press, London’s mice-eyed must have begun their search for the shadowy four; it has not slacked since. As to those nominated as ‘Mr. W.H.’, the list ranges from William Herbert to Henry Wroithesley (with initials reversed) to William Harvey (Wroithesley’s stepfather). In 1964 Leslie Hotson proposed one William Hatcliffe of Lincolnshire [!], while Thomas Tyrwitt, Edmond Malone, and Oscar Wilde all favoured a (fictional) boy actor, Willie Hughes. Among candidates for the ‘fair youth’, Henry Wroithesley, Earl of Southampton (1573–1624), appears to have outlasted all comers. Those proposed as the rival poet include Christopher Marlowe (more interested in boys than ladies dark or light); Samuel Daniel (Herbert’s sometime tutor);2 Michael Drayton, drinking partner of Jonson and Shakespeare; George Chapman, whose Seaven Bookes of the Iliades (1598) were a source for Troilus and Cressida; and Barnabe Barnes, lampooned by Nashe as ‘Barnaby Bright’ in Have with you to Saffron-Walden. -

Introduction to the Puritans: Memorial Edition

Introduction to the Puritans Memorial Edition Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) INTRODUCTION TO THE PURITANS Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) Memorial Edition A Tribute to the Life and Ministry of Erroll Hulse Dedicated to the memory of Erroll Hulse with great joy and gratitude for his life and ministry. Many around the world will continue to benefit for many years to come from his untiring service. Those who knew him, and those who read this volume, will be blessed by his Christ- honoring life, a life well-lived to the glory of God. The following Scripture verses, psalm, and hymns were among his favorites. ISAIAH 11:9 They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. HABAKKUK 2:14 For the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. PSALM 72 1Give the king thy judgments, O God, and thy righteousness unto the king’s son. 2He shall judge thy people with righteousness, and thy poor with judgment. 3The mountains shall bring peace to the people, and the little hills, by righteousness. 4He shall judge the poor of the people, he shall save the children of the needy, and shall break in pieces the oppressor. 5They shall fear thee as long as the sun and moon endure, throughout all generations. 6He shall come down like rain upon the mown grass: as showers that water the earth. 7In his days shall the righteous flourish; and abundance of peace so long as the moon endureth. -

The Glass No. 11, Winter 1998

THE GLASS THE GLASS NUMBER 11 WINTER 1998 Editorial 2 ‘Mercie, mercie to crye and crye again’: repentance and resolution in Anne Lock’s Meditation of a Penitent Sinner Jill Seal 3 Escape to Wallaby Wood: C S Lewis’s Depictions of Conversion Michael Ward 16 Old Western Man for Our Times: C S Lewis’s Literary Criticism Stephen Logan 33 From Pillar to Post: A Response to David Tomlinson’s The Post- Evangelical Kevin Mills 50 Reviews 58 Notes on Contributors 62 News and Notes 63 Published by the Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship (UCCF) for the Literary Studies Group. UCCF 38 De Montfort Street Leicester LE1 7GP Tel 0116 255 1700 www.uccf.org.uk [email protected] © The contributors 1998 ISSN 0269-770X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any1 form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. The views of the contributors do not necessarily reflect editorial stance. UCCF holds personal details on computer for the purpose of mailing in accordance with terms registered under the Data Protection Act 1984 – details available on request. THE GLASS Editorial Even those who have done courses in 16th century English literature may not be familiar with the name of Anne Lock, yet she is the poetic creator of a remarkable sonnet cycle based on Psalm 51, the psalm of Davidic repentance. Anne Lock was in fact a pioneer of the sonnet form, and her opus, presented in this issue by Jill Seal − whose research may also be fairly described as pioneering − is the earliest known sonnet sequence in English. -

CONTENTS Editorial I Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

VOL. LVI. No. 173 PRICE £1 函°N加少 0 December, 1973 CONTENTS Editorial i Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford ... 11 Othello ... 17 Ex Deo Nascimur 31 Bacon's Belated Justice 35 Francis Bacon*s Pictorial Hallmarks 66 From the Archives 81 Hawk Versus Dove 87 Book Reviews 104 Correspondence ... 111 © Published Periodically LONDON: Published by The Francis Bacon Society IncorporateD at Canonbury Tower, Islington, London, N.I, and printed by Lightbowns Limited, 72 Union Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight. THE FRANCIS BACON SOCIETY (INCORPORATED) Among the Objects for which the Society is established, as expressed in the Memorandum of Association, are the following 1. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the study of the works of Francis Bacon as philosopher, statesman and poet; also his character, genius and life; his- — . influence: — £1._ _ — — — on his1" — own and J succeeding— J : /times, 〜— —and the tendencies cfand」 v*results 否 of his writing. 2. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the general study of the evidence in favour of Francis Bacon's authorship of the plays commonly ascribed to Shakespeare, and to investigate his connection with other works of the Elizabethan period. Officers and Council: Hon, President: Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Past Hon, President: Capt. B, Alexander, m.r.i. Hon. Vice-Presidents: Wilfred Woodward, Esq. Roderick L. Eagle, Esq. Council: Noel Fermor, Esq., Chairman T. D. Bokenham, Esq., Vice-Chairman Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Nigel Hardy, Esq. J. D. Maconachie, Esq. A. D. Searl, Esq. Sidney Filon, Esq. Austin Hatt-Arnold, Esq. Secretary: Mrs. D. -

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner and the Problem of Ascription

This is a pre-publication draft of this article and should not be used for citation purposes. Deirdre Serjeantson [email protected] Anne Lock’s anonymous friend: A meditation of a penitent sinner and the problem of ascription Christopher Goodman lived most of his adult life on the wrong side of prevailing orthodoxies. At the accession of Queen Mary, Goodman was the Lady Margaret professor of divinity at Oxford: finding himself out of sympathy with the state’s reversion to Catholicism, he went into exile on the continent. He joined his English co-religionists at Frankfurt in 1554, but when the congregation quarrelled over the use of the 1552 Prayer Book, Goodman was one of the faction which could not be reconciled, and he left for Calvin’s Geneva in 1555. In that more congenial atmosphere he wrote his 1558 treatise, How superior powers ought to be obeyed , which, like John Knox’s notorious First blast of the trumpet against the monstrous regiment of women (1558), argued against the legitimacy of female monarchs. The books were primarily motivated by their opposition to the rule of Queen Mary, who was disqualified, they argued, for reasons of religion as well as gender. Their comments were ill- timed, coinciding as they did with Mary’s death and the coronation of another queen. For all that Goodman had praised her – a ‘Godlie Lady, a[n]d meke Lambe, voyde of all Spanishe pride, and strange bloude’ (Mary, by contrast, was an ‘vngodlie serpent’) – Elizabeth took a dim view of both books. 1 Her religious views may have been more acceptable to the authors, but their attack on female monarchy appears to have gravely offended her: in June 1559, William Cecil, writing from the Court, reported that ‘Of all others, Knoxees name, if it be not Goodmans, is most odiose here.’ 2 Prudently, both men established themselves in Scotland on their return from Geneva; however, when the earl of Moray’s rebellion in 1565 forced Goodman to seek office in territories controlled by Elizabeth, he was to find his advancement implacably blocked. -

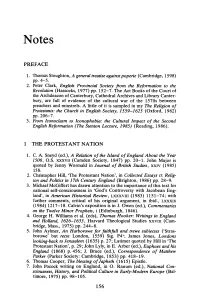

Preface 1 the Protestant Nation

Notes PREFACE 1. Thomas Stoughton, A general treatise against poperie (Cambridge, 1598) pp.4-5. 2. Peter Clark, English Provincial Society from the Reformation to the Revolution (Hassocks, 1977) pp. 152-7. The Act Books of the Court of the Archdeacon of Canterbury, Cathedral Archives and Library Canter bury, are full of evidence of the cultural war of the 1570s between preachers and minstrels. A little of it is sampled in my The Religion of Protestants: the Church in English Society, 1559-1625 (Oxford, 1982) pp.206-7. 3. From Iconoclasm to Iconophobia: the Cultural Impact of the Second English Reformation (The Stenton Lecture, 1985) (Reading, 1986). 1 THE PROTESTANT NATION 1. C. A. Sneyd (ed.), A Relation of the Island of England About the Year 1500, O.S. XXXVII (Camden Society, 1847) pp. 20-1. John Major is quoted by Jenny Wormald in Journal of British Studies, XXIV (1985) 158. 2. Christopher Hill, 'The Protestant Nation', in Collected Essays II: Relig ion and Politics in 17th Century England (Brighton, 1986) pp. 28-9. 3. Michael McGiffert has drawn attention to the importance of this text for national self-consciousness in 'God's Controversy with Jacobean Eng land', in American Historical Review, LXXXVIII (1983) 1151-74; with further comments, critical of his original argument, in ibid., LXXXIX (1984) 1217-18. Calvin's exposition is in J. Owen (ed.), Commentaries on the Twelve Minor Prophets, I (Edinburgh, 1846). 4. George H. Williams et al. (eds), Thomas Hooker: Writings in England and Holland, 1626-1633, Harvard Theological Studies XXVIII (Cam bridge, Mass., 1975) pp. -

Religion for Further Reading

1 Chapter Six: Religion For Further Reading Wide-ranging collections of articles provide a good place to begin if you wish an overview of women’s role in religion. Some of the best include Rosemary Radford Ruether, Religion and Sexism: Images of Woman in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1974); Rosemary Radford Ruether and Eleanore McLaughlin (eds.), Women of Spirit: Female Leadership in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1979); Richard L. Greaves (ed.), Triumph Over Silence: Women in Protestant History (Westport, CT, Greenwood, 1985); Lynda L. Coon et al. (eds.), That Gentle Strength: Historical Perspectives on Women in Christianity (Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1990); W. J. Shields and Diana Wood (eds.), Women in the Church, Studies in Church History, vol. 27 (Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990); Judith Baskin (ed.), Jewish Women in Historical Perspective (Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1991); Kari Elizabeth Borreson and Kari Vogt (eds.), Women’s Studies of the Christian and Islamic Traditions: Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Foremothers (Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic, 1993); Daniel Bornstein and Roberto Rusconi (eds.), Women and Religion in Medieval and Renaissance Italy (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1996); Beverly Mayne Kienzle and Pamela J. Walker (eds.), Women Preachers and Prophets through Two Millennia of Christianity (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998). 2 Two collections focus only on the early modern period, with articles about women in many countries, are Sherrin Marshall (ed.), Women in Reformation and Counter- Reformation Europe: Public and Private Worlds (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1989), and Susan E. Dinan and Debra Meyers (eds.), Women and Religion in Old and New Worlds (New York, Routledge, 2001). -

The Dark Lady of the Merchant of Venice

3 The dark lady of The Merchant of Venice ‘The Sonnets of Shakespeare offer us the greatest puzzle in the history of English literature.’ So began the voyage of Alfred Leslie Rowse (1903–97) through the murky waters cloaking the identi- ties of four persons associated with the publication in 1609 of Shakespeare’s ‘sugared sonnets’: the enigmatic ‘Mr. W.H.’ cited in the forepages as ‘onlie begetter’ of the poems; the unnamed ‘fair youth’ addressed in sonnets 1–126; the ‘rival poet’ who surfaces and submerges in sonnets 78–86; and the mysterious ‘dark lady’ celebrated and castigated in sonnets 127–52.1 Doubtless, even as Thomas Thorpe’s edition was passing through George Eld’s press, London’s mice-eyed must have begun their search for the shadowy four; it has not slacked since. As to those nominated as ‘Mr. W.H.’, the list ranges from William Herbert to Henry Wroithesley (with initials reversed) to William Harvey (Wroithesley’s stepfather). In 1964 Leslie Hotson proposed one William Hatcliffe of Lincolnshire [!], while Thomas Tyrwitt, Edmond Malone, and Oscar Wilde all favoured a (fictional) boy actor, Willie Hughes. Among candidates for the ‘fair youth’, Henry Wroithesley, Earl of Southampton (1573–1624), appears to have outlasted all comers. Those proposed as the rival poet include Christopher Marlowe (more interested in boys than ladies dark or light); Samuel Daniel (Herbert’s sometime tutor);2 Michael Drayton, drinking partner of Jonson and Shakespeare; George Chapman, whose Seaven Bookes of the Iliades (1598) were a source for Troilus and Cressida; and Barnabe Barnes, lampooned by Nashe as ‘Barnaby Bright’ in Have with you to Saffron-Walden. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 J. Mush, An Abstracte of the Life and Martirdome of Mistres Margaret Clitherow (Mechelen, 1619), sig. A2±A2v. 2 Troubles of Our Catholic Forefathers Related by Themselves, ed. J. Morris (London, 1877), vol. 3, p. 432; The Chronicle of the English Augustinian Canonesses Regular of the Lateran, at St Monica's in Louvain (now at St Augustine's Priory, Newton Abbot, Devon) 1548±1644, ed. A. Hamilton, hereafter Chronicle of St Monica's (London, 1904), vol. 1, pp. 33±4. 3 Chronicle of St Monica's, vol. 1, pp. 16±17, 33, 46±55, 80±4, 175±9, 189±90, 205±6; vol. 2, pp. 164±8. 4 H. Peters, Mary Ward: A World In Contemplation, trans. H. Butterfield (Leomin- ster, 1994); J. Cameron, A Dangerous Innovator: Mary Ward 1585±1645 (Sydney, 2000); M. Wright, Mary Ward's Institute: The Struggle for Identity (Sydney, 1997); P. Guilday, The English Catholic Refugees on the Continent 1558±1795 (London, 1914), pp. 163±214; St Mary's Convent, Micklegate Bar, York (1686±1887), ed. H. J. Coleridge (London, 1887). 5 Their publications on the history and archives of convents and individuals are too numerous to list, but the principal journals include: Recusant History; Downside Review; Ampleforth Journal; Essex Recusant; London Recusant; Northern Catholic History; Staffordshire Catholic History; Catholic Archives. See also the CRS records and monographs series. The two standard studies of the convents abroad are Guilday, Catholic Refugees; and B. Whelan, Historic English Convents of Today: The Story of the English Cloisters in France and Flanders in Penal Times (London, 1936). -

Othello` (Version II, in English) Lev I

[Введите текст] On the hidden meaning of Shakespeare's tragedy `Othello` (Version II, in English) Lev I. Verkhovsky Shakespeare's tragedy "Othello" is considered by many to be the most perfect from the works of Shakespeare. Some people inclined to consider it even as the most perfect dramatic creation in the world. A. Blok Exactly a century ago, in October 1919, Alexander Blok gave a lecture to the actors of the Bolshoi Drama Theater “The secret meaning of the tragedy "Othello", which was published at the same time. In it, he tried to reveal the reasons why this work of art so deeply affects the viewer and reader. We are going to reflect on the secret meaning of "Othello" from a completely different angle. Plays by Shakespeare (and also by Ben Jonson and other Elizabethans) often contained second, hidden plans. In them, playwrights portrayed famous people or their acquaintances, sorted out relationships, settled scores; only people of their circle could see and understand this. It is clear that such hidden information is always closely related to the personality of a particular author, therefore, its consideration in the case of `Othello`, in our opinion, is important for solving Shakespeare's question. Chapter 1 `The Tragedy of Othello, The Moor of Venice` was first staged at the Globe Theater in November 1604, and was probably written not long before. It appeared in print only in 1622 in the form of a quarto, and a year later a slightly different, expanded version of it was presented in the First Folio; what is the relationship of these two texts is still not clear. -

A Half-Closed Book

A HALF-CLOSED BOOK Compiled by J. L. Herrera TO THE MEMORY OF: Mary Brice AND WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: Madge Portwin, Margaret Clarke, Isla MacGregor, Bob Clark, Betty Cameron, Ken Herrera, Cheryl Perriman, and sundry libraries, op-shops, and book exchanges INTRODUCTION Just one more ramble through unexpected byways and surprising twists and turns … yes, I think everyone is allowed to go out with neither bang nor whimper but with her eyes glued to the page … Poor dear, people can say, she didn’t see that bus coming … The difficulty of course is where to store everything; and finding room in my mind is sometimes as tricky as finding room in my bedroom. But was it a good idea to do a short writer’s calendar? A year instead of my usual three years. I had mixed feelings about it. It was nice to see a book take shape so (relatively) swiftly. But I also felt the bits and pieces hadn’t had time to marinate fully. That sense of organic development had been hurried. I also found I tended to run with the simpler stories rather than the ones that needed some research—and some luck, some serendipity. On the other hand, how long a soaking constitutes a decent marinade? Not being a good cook I always find that hard to decide … So this will be a book without a deadline. One which can just wander along in spare moments. Its date will have to wait. Even so, I hope that anyone who happens to read it some day will enjoy it as much as I always enjoy the compiling of books on writing and reading. -

The Role of Women in the English Reformation Illustrated by the Life and Friendships of Anne Locke

The Role of Women in the English Reformation illustrated by the Life and Friendships of Anne Locke PATRICK COLLINSON Lecturer in Ecclesiastical History, Kings College, University of London HE notable part played by women in the Reformation has rarely been given its due recognition in English historical T studies. In recent years Professor Wallace Notestein has written with characteristic authority and grace on 'The English Woman, 1580-1650,'x but one does not learn from this essay that the English women of this age had any religious propensities at all. And leaving aside the more prominent figures such as Queen Catherine Parr, Lady Jane Grey, and Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk, women make but few appearances in most accounts of the English Reformation. This is no doubt only one symptom of the tendency of so many of our histories to dwell upon the officially inspired aspects of the Reformation to the neglect of the spontaneous and the local; to be concerned with the making of settlements and their enforce ment rather than with the means by which Protestantism actually spread in families, towns, and other communities. And of course there are special factors which obscure the female contribution to history, the legal disabilities of the sex, which so often hide the married woman and allow us to catch glimpses only of the widow, a 'person' in law. Yet in France, where by the nature of the case a more sensitive historical criticism has had to be directed towards what Americans might call the grass-roots of Protestantism, the supreme importance of women in its propagation has not been missed.