What Is Medium Wave Dxing?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IARU and You

Howard E. Michel, WB2ITX, ARRL Chief Executive Officer, [email protected] Second Century The IARU and You April 18 is World Amateur Radio Day. The International Amateur Radio Union (IARU) has selected the observance’s theme for 2019: “Celebrating Amateur Radio’s Contribution to Society.” Some of you may ask, “What is the IARU, and why should I care?” The International Amateur Radio Union is a federation of ARRL and IARU have been preparing for this conference, national Amateur Radio associations, founded on April and to protect Amateur Radio spectrum. 18, 1925 in Paris with representatives from an initial 25 countries. ARRL is the International Secretariat for Because of this critically important service that IARU the IARU, and also represents the United States in provides, it has grown to include 160 member- the IARU. The International Telecommunication societies in three regions. These regions are orga- Union (ITU), which is the United Nations special- nized to roughly mirror the structure of the ITU and ized agency for information and communication its related regional telecommunications organiza- technologies (ICTs), has recognized the IARU as tions. IARU Region 1 includes Europe, Africa, the representing the worldwide interests of Amateur Radio. Middle East, and Northern Asia. Region 2 covers the Americas, and Region 3 comprises Australia, New The ITU has three main areas of activity called sectors: Zealand, the Pacific island nations, and most of Asia. radiocommunications, standardization, and development. Working through these sectors, ITU allocates global radio According to the IARU, there are about 3 million hams spectrum and satellite orbits, develops the technical stan- worldwide. -

The Results for You to Think About

Ottawa Amateur Radio Club MONTHLY CLUB MEETING APRIL 7, 2020 7:30PM 1 COVID-19 REMINDERS Wash your hands…don’t touch your face…shake feet not hands…sneeze or cough into your elbow or tissue… And most importantly (for whatever reason) …use toilet paper sparingly and stock up! 2 Agenda • Member Survey Results for How we can re-imagine the use of our Repeater during this current COVID-19 to bring value to our members • Proposed Discussion Topics •Proposed Schedule •Proposed Meeting Format 3 Topics Popularity Ranking Building antennas 10.48 Building accessories 9.9 Building radios 9.52 Computer supported modes like FT8, RTTY, PSK31 8.9 QRP operations 8.76 VHF Digital Modes - DMR, C4FM Fusion, and DSTAR 8.43 APRS 7.86 HF contesting 7.67 Fox Hunting 7.62 Satellite operations including EME (moon bounce) 7.19 VHF and up DXing 6.86 Slow Scan TV 4.67 LF or MF operations 3.95 Other 3.19 4 Knowledge and Experience Ranking 4- 1-NOVICE– 2-INTERMEDIATE–3-ADVANCED– EXPERT– TOTAL– WEIGHTED AVERAGE– Building accessories 2 11 6 2 21 2.38 Building antennas 3 11 6 1 21 2.24 Building radios 7 10 4 0 21 1.86 APRS 11 6 3 1 21 1.71 HF contesting 13 5 2 1 21 1.57 Computer supported modes like FT8, RTTY, PSK31 15 3 1 2 21 1.52 VHF Digital Modes - DMR, C4FM Fusion, & DSTAR 12 6 2 0 20 1.5 Fox hunting 12 8 1 0 21 1.48 QRP operations 15 4 2 0 21 1.38 Other: __________________________________ 12 3 1 0 16 1.31 VHF and up DXing 16 4 0 0 20 1.2 Slow Scan TV 17 3 0 0 20 1.15 Satellite operations, EME (Moon Bounce) 18 3 0 0 21 1.14 LF or MF operations 19 0 1 0 20 1.1 5 What I like most about creating more opportunities to discuss focused topics during NETs • lively and imaginative discussions. -

The Am Broadcast Band

THE AM BROADCAST BAND While crystal sets are designed, built, and used for the AM broadcast band and shortwave bands, the vast majority of hobbyists in the US focus their activities on the AM band, defined by the FCC to span from 530 through 1,700 kHz. As of January 1, 2008, there were roughly 4,793 AM stations active on the band, and this number of stations hasn’t changed much over the last ten years. Power output assigned by license to these stations varies, from as little as 250 watts to a maximum of 50,000 watts. Format, i.e. the content broadcast by each station, varies. As noted in Figure 1, the concentration of AM stations assigned at each increment of 10 kHz in frequency varies across the band, numbering 25 at 540 kHz, averaging about 30 from 550 through 1200 kHz and about 65 from 1210 through 1600 kHz. Just a smattering of stations occupy segments from 1600-1700 kHz. Figure 2 displays the concentration per frequency for the 50 Kilowatt stations that operate day and night. These stations - often called clear-channel stations – can cover a wide area at night as their radio signals reflect off the ionosphere. During the day, local stations are those most often heard, as long-distant reflections off the ionosphere are reduced. Clearly, we can use these facts to improve our listening and logging activities. During the day is the best time to receive or log those stations that are within a given radius of our location. At night the clear-channel stations will dominate and we’ll tend to hear those whose antenna pattern (direction of transmission) and reflection pattern (for that day) off the ionosphere is aimed at our location. -

The 630 Meter Band

The 630 Meter Band Introduction The 630 meter Amateur Radio band is a frequency band allocated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to the Amateur Service, and ranges from 472 to 479 kHz, or equivalently 625.9 to 635.1 meters wavelength. It was formally allocated to the Amateur Service as part of the Final Acts of the 2012 World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC-12). Once approved by the appropriate national regulatory authority, the band is available on a secondary basis to countries in all ITU regions with the limitation that Amateur stations have a maximum radiated power of 1 Watt effective isotropic radiated power (EIRP). Stations more than 800 km from certain countries (listed below) may be permitted to use 5 Watts EIRP however. The ITU Final Acts took effect 1 January 2013 and after public consultation on all of the ITU allocation changes contained it, the 630 meter band was added to the Canada Table of Frequencies in 2014. Several countries had previously allocated the WRC-12 band to Amateurs domestically. Several other countries had also already authorized temporary allocations or experimental operations on nearby frequencies. The band is in the Medium Frequency (MF) region, within the greater 415–526.5 kHz maritime band. The first International Wireless Telegraph Convention, held in Berlin on November 3, 1906, designated 500 kHz as the maritime international distress frequency. For nearly 100 years, the “600-meter band” (495 to 510 kHz) served as the primary calling and distress frequency for maritime communication, first using spark transmissions, and later CW. In the 1980s a transition began to the Global Maritime Distress Signaling System (GMDSS), which uses UHF communication via satellite. -

UTARC N5XU MF/HF Station

UTARC N5XU MF/HF Station The N5XU HF station is designed with DXing and single-operator or multi-single radio contesting in mind. All of the equipment is located on a single table, with almost everything located within comfortable reach of the operator. The equipment is on a single table and shelf. On the top shelf, left to right: small B&W portable television sitting on top of an Astron RS-20A 13.8VDC power supply, an AEA PK-900 multimode data controller sitting on top of a Curtis Command Center The HF station at N5XU power distribution switch, a desk lamp, a 17" computer monitor, small MFJ 24-hour clock, a Logikey K-3 CW memory keyer, a large bell, CDE Ham IV rotor control head, Kenwood AT- 230. Under the shelf, left to right: Astron RS-20M 13.8VDC power supply, Yaesu FT-2600M, Kenwood SP-31 speaker, Kenwood TS-850SAT, Kenwood IF-232C (under table, not visible,) Radio Shack Digital SWR/Power Meter, Kenwood VFO-230, Kenwood TS-830S. On the table, left to right: Optimus 71 headphones, Electrovoice Model 638 microphone with Heil HC-4 element, computer keyboard, mouse, Bencher BY-1 paddles, Optimus PRO-50MX headset microphone. In the rack, from top to bottom: AM-6155 400 watt amplifier for 222 MHz, Tektronix RM 503 dual-trace oscilloscope, antenna patch panel, Heathkit SB-220 linear amplifier with large muffin fan on top. Our main HF transceiver is a Kenwood TS-850SAT. This radio is capable of CW, USB, LSB, FSK, AM, FM. and PSK modes on all of the MF and HF Amateur Radio bands. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

The Global Alliance on Media and Gender (Gamag) Framework and Plan of Action

THE GLOBAL ALLIANCE ON MEDIA AND GENDER (GAMAG) Promoting and addressing gender equality and women’s empowerment in media systems, structures and content FRAMEWORK AND PLAN OF ACTION FRAMEWORK AND PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE GLOBAL ALLIANCE ON MEDIA AND GENDER (GAMAG) Promoting and addressing gender equality and women’s empowerment in media systems, structures and content. Preamble The Beijing Declaration put on the map the critical importance of media in the attainment of gender equality and women’s empowerment. Twenty years later, while there have been signs of progress, and meantime the media environment has been significantly transformed. There is a need to revitalize our commitment and approach to the relationships between gender equality and the media in the 21st century. The new media environment, which includes social and digital media, increasingly complex market pressures and globalized media systems, provides new opportunities for women’s freedom of expression and access to information. Yet it exacerbates some existing problems and throws up new challenges that need to be addressed. The first Global Forum on Media and Gender (2-4 December, Bangkok, Thailand) aimed to initiate processes that would link up ongoing actions and add momentum to efforts to address the issue of gender equality in media systems, structures and content, acknowledging this as a key to women’s empowerment and full participation in society. Following a global discussion on the framework and plan of action for GAMAG, the forum committed to the following development goal: To catalyse the changes and partnerships needed to ensure that gender equality is achieved in constantly evolving media systems, structures and content at local, national and global levels. -

Specifications of Shortwave Radios from Various Manufacturers

http://entropy.brneurosci.org/radio-misc.html Specifications of shortwave radios from various manufacturers Last updated June 6, 2006 The information below was compiled during my (so far unsuccessful) search for the ideal shortwave radio to replace my old Sony ICF-2010. I discovered that there was so much information to digest, the only way to organize it was to put it on a Web page. Much of this information has been pasted directly from the vendors' Websites and may or may not be factually correct. Where the information is known to be incorrect or misleading, this is noted. Most of the opinions are my own, based mostly on the publicly available specifications and comments from various Internet sources. The information describes the specifications of receivers that I have not tested, and summarizes the opinions that seem to be generally held about each receiver based on comments I found on the Internet. I have not personally verified any of this information. In case you're interested, I decided not to buy any of the radios listed here, but repaired my old Sony instead. Receivers Drake R8B Icom R9000 Icom R8500 AOR AR5000 AOR SR1050 Ten-Tec RX-350D Icom R75 Icom IC-PCR1500 and IC-R1500 Icom IC-PCR1000 Kaito WRX-911 Palstar R30 Grundig YB300 Grundig G2000A Grundig YB550 Grundig YB400 Grundig Satellit 800 Eton E1XM Panasonic RF-4900 Yaesu FRG-7 AOR AR-3030 AOR AR-8600 Mark 2 Collins 95S Sony ICF-SW7600 Sony ICF-SW77 Sony ICF-SW2010 Sony ICF-100 Yaesu FRG-9600 Yaesu FRG-100 Review Review AOR AR-One Lowe HF-150 AOR AR7030+ JRC NRD-545 Kenwood R5000 JRC NRD-525 Icom IC-R3 Yaesu VR-5000 Ten-Tec RX-331 Ten-Tec RX-340 Sangean ATS-909 Ten-Tec RX-320D Software-defined radios The number of software defined receivers is exploding. -

Republic of Liberia Appendices

TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Media and Outreach in the TRC Process REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Volume Three: APPENDICES Title VI: Media and Outreach in the TRC Process Volume THREE, Title VI i PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/a14fc8/ TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Media and Outreach in the TRC Process ii Volume THREE, Title VI PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/a14fc8/ TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Media and Outreach in the TRC Process Final Statement from the Commission Nearly three and half years ago, we embarked upon a journey on behalf of the people of Liberia with a simple mission to explain how Liberia became what it is today and to advance recommendations to avert a repetition of the past and lay the foundation for sustainable national peace, unity, security and reconciliation. Considering the complexity of the Liberian conflict, the intractable nature of our socio-cultural interactions, the fluid political and fragile security environment, we had no illusion of the task at hand and, embraced the challenge as a national call to duty; a duty we commi<ed ourselves to accomplishing without fear or favor. Today, we have done just that! With gratitude to the Almighty God, the Merciful Allah and our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, we are both proud and honored to present our report to the people of Liberia, the Government of Liberia, the President of Liberia and the International Community who are “moral guarantors” of the Liberian peace process. This report is made against the background of rising expectations, fears and anxiety. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 82, No. 7●December 29, 2014● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 11 … Domestic DX Digest East 16 … College Sports Networks 5 … Membership Report 14 … International DX Digest 17 … Treasurer’s Report 6 … Domestic DX Digest West 15 … Musings of the Members 18 … Geo Indices/Space Wx Board Announcement: The NRC Board of DecaloMania in Fort Wayne, Indiana, July 10‐12, Directors is pleased to announce the 2015. More details will be forthcoming as our appointment of its newest member to the BoD to host Scott Fybush works them out. fill the vacant seat left by Ken Chatterton after DX Tests: If you want to help arrange tests, his resignation earlier this year. Dave Schmidt, contact Brandon Jordan, the NRC/IRCA Test who has served as Musings of the Members Coordination, at P.O. Box 338, Rossville TN editor for over twenty years and DDXD editor 38066, (901) 592‐9847, and [email protected]. before that, is our newest BoD member. Dave Brandon has set up a web site at also has a keen interest in record collecting and http://dxtests.net/ for the latest test info. And Internet radio (maybe he’ll tell you more in a follow him on Twitter @AMDXTests for the latest Musing soon!). Welcome, Dave! – Paul test info. Swearingen, NRC BoD Chairman. PARI DXpedition: Via the NASWA Journal, DXAS: Fred Vobbe has announced that he Thomas Witherspoon is planning a unique will be stepping down as publisher of the DX DXpedition to the Pisgah Astronomical Research Audio Service after the April 2015 issue. -

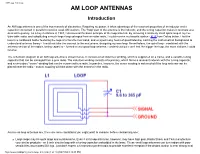

AM Loop Antennas AM LOOP ANTENNAS Introduction

AM Loop Antennas AM LOOP ANTENNAS Introduction An AM loop antenna is one of the true marvels of electronics. Requiring no power, it takes advantage of the resonant properties of an inductor and a capacitor connected in parallel to receive weak AM stations. The "loop" part of the antenna is the inductor, and the tuning capacitor makes it resonate at a desired frequency. As a boy in Abilene in 1967, I discovered the basic principle of the loop antenna. By removing a relatively small spiral loop in my five tube table radio, and substituting a much larger loop salvaged from an older radio, I could receive my favorite station - KLIF from Dallas better. I hid the loop in a cardboard holder featuring the logo of a favorite rock band, and enjoyed many hours of good listening. Lacking the mathematical background to understand antenna theory - I could not take the concept to the next phase: designing my own loop. Nevertheless, the spiral loop - combined with the antenna section of the radio's tuning capacitor - formed a very good loop antenna. I understood quite well that the bigger the loop, the more stations I could receive. The schematic diagram of an AM loop antenna is shown below. It consists of an inductive winding, which is supported on a frame, and a variable tuning capacitor that can be salvaged from a junk radio. The inductive winding consists of a primary, which forms a resonant network with the tuning capacitor, and a secondary "sense" winding that can be connected to a radio. In practice, however, the sense winding is not needed if the loop antenna can be placed near the radio - mutual coupling will take place with the antenna in the radio. -

Transnationalizing Radio Research

Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research Media Studies | Volume 42 Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research New Approaches to an Old Medium . Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld Typeset: Anja Richter Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-3913-1 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-3913-5 Contents INTRODUCTION Transnationalizing Radio Research: New Encounters with an Old Medium Alexander Badenoch