1. Surface Tension, Screen Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology

MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology The MIT Visual Arts Program (VAP) and the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) merged in July 2009 to form the MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT). This spring, ACT proudly celebrated its inauguration at its new home in the Media Lab complex (E14) and the Wiesner Building (E15). This new program draws on the impressive legacies of VAP (founded 20 years ago) and CAVS (founded in 1967). Focusing on the intersections of art, culture, and technology through performance, sound, video/film, photography, interrogative and eco-design, as well as experimental media and new genres, ACT’s academic and research initiatives reflect the mission of the new program, which is to operate as a laboratory based on critical studies and production, connecting artists and cultural producers with those working at the forefront of technology. ACT’s faculty, fellows, and students take an experimental and systematic approach to creative production and transdisciplinary collaboration, with the goal of furthering and disseminating advanced visual studies and research at the intersection of art, culture, and technology. The program emphasizes art that engages public spheres, the production of space, networked cultures, and participatory media while addressing such issues as the environment, gender, and social stratification. In the tradition of the founder of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, Hungarian-born artist Gyorgy Kepes, a gifted educator and advocate of “art on a civic scale,” ACT envisions artistic leadership as initiating change and providing a critically transformative view of the world with the civic responsibility to enrich cultural discourse. -

Akram Zaatari's

8/22/13 Two Point Perspective: Akram Zaatari’s “Letter to a Refusing Pilot” | Art21 Blog HOME GUEST BLOG EDUCATION VIDEO current theme: networks search BLOGGER-IN-RESIDENCE: Noah Simblist, Curator, Writer, and Professor, Dallas, TX Two Point Perspective: Akram Zaatari’s Jʼaime 68 “Letter to a Refusing Pilot” Tweet 6 subscribe July 23rd, 2013 by Noah Simblist Art21 Blog feed Video feed Education feed Guest Blog feed featured film communicate Barry McGee: Retrospective pages About Art21 new york close up About the Art21 Blog Current Contributors art21 online on Art21.org Akram Zaatari. “Letter to a Refusing Pilot (still),” 2013. Film and video installation. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut. on Blip.tv on Del.icio.us Stories can have a life of their own. They are told, heard, told again, written down, archived, Jacolby Satterwhite Dances with recorded, and gathered together with supporting documents, photographs or film. A story, His Self on Facebook especially in the context of war, can fragment, multiply, and turn into a series of contractions. on Flickr The veracity of a story’s truth becomes increasingly elusive when one has to choose between teaching with on iTunes an individual’s partial understanding of a situation and the unreliable grand narratives told to contemporary art on PBS us by power brokers who are first and foremost driven by ideology. This condition haunts on Twitter many of the artworks that have emerged in Beirut these past twenty years. on YouTube blogroll 16 Miles of String 2 Buildings 1 Blog In and out of the classroom Art Fag City Art Whirled blogger-in-residence Artlog ArtsBeat Bad at Sports BAM 150 BOMBlog C-Monster Dorothy Santos, Visual and Creative Capital – The Lab Critical Studies Geek, San Culture Monster Francisco, CA Ed Winkleman Akram Zaatari. -

PRESS RELEASE Unlimited

PRESS RELEASE Unlimited: Presenting 76 premier works This year's edition of Unlimited will consist of 76 large-scale projects, presented by galleries participating in the fair. Curated for the sixth consecutive year by Gianni Jetzer, curator-at-large at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., the sector will feature a wide range of presentations, from historically significant pieces to the latest contemporary works. Renowned as well as emerging artists will participate, including: Doug Aitken, Carl Andre, John Baldessari, Andrea Bowers, Chris Burden, Julian Charrière and Julius von Bismarck, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Carlos Garaicoa, Subodh Gupta, Jenny Holzer, Donna Huanca, Arthur Jafa, Barbara Kruger, Cildo Meireles, Bruce Nauman, Park Chan-kyong, Marwan Rechmaoui, Mickalene Thomas and Anicka Yi. Art Basel, whose Lead Partner is UBS, takes place at Messe Basel from June 15 to June 18, 2017. Presented across 16,000 square meters of exhibition space, Unlimited has provided galleries – since its introduction in 2000 – with a unique opportunity to showcase monumental sculptures, video projections, wall paintings, photographic series and performance art that transcend the traditional art-fair stand. In ‘Cooking the World’ (2017) Subodh Gupta (b. 1964) recreates a shelter made entirely from aluminum utensils, in which he carries out a cooking and eating performance, commemorating these ritualistic practices. Also incorporating performance, ‘BLISS (REALITY CHECK)’ (2017) by Donna Huanca (b. 1980) is an elaborate installation comprised of a tableaux vivant of props, painterly elements and actors, designed to suspend the viewer between the role of a passive onlooker and an active performer. ‘Underwater Pavilions’ (2017) by Doug Aitken (b. -

The Effect of New Media on Contemporaneity of the Works by Krzysztof Wodiczko Pjaee, 18 (4) (2021)

THE EFFECT OF NEW MEDIA ON CONTEMPORANEITY OF THE WORKS BY KRZYSZTOF WODICZKO PJAEE, 18 (4) (2021) THE EFFECT OF NEW MEDIA ON CONTEMPORANEITY OF THE WORKS BY KRZYSZTOF WODICZKO Sepideh Takshi1, Mohammad Kazem Hassanvand2* 1M.A., Department of Painting, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. 2*Assistant Professor, Department of Painting, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. [email protected] Sepideh Takshi, Mohammad Kazem Hassanvand. The Effect of New Media on Contemporaneity of the Works by Krzysztof Wodiczko-- Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4), 7651-7663. ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Contemporary, Medium, Rendering, Situation. Abstract Attentions were paid to media since the second half of the twentieth century and it was with the technological progresses that the number of the media was increased and a vast ground was in addition set for the artists to grant a power of manifestation to their ideas. The present study aims at finding an answer to the question as to how have the new media influenced the contemporaneity of the works by artists, especially Krzysztof Wodiczko? In order to find an answer to this question, the definition and specifications of contemporaneousness should be studied and investigated hence it is proposed that how much have media influenced contemporaneity of the works by various artists. Considering the study, technological progresses and the application of the new media, especially of the digital type, have enabled more interaction between the audience and the artworks to the extent that the former is no longer just an observer; thus, contemporaneity of the artworks is not specific to the time in a historical sense and numerous factors have caused the artworks to become contemporaneous; media are amongst these factors. -

Ch 34 Study Guide Questions Set #3 You Must Answer All Questions in This Set in Order to Be Exempt from the Ch 34 Quiz #3. 1. Wh

Ch 34 Study Guide Questions Set #3 You must answer all questions in this set in order to be exempt from the Ch 34 Quiz #3. 1. What role did Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro play in the American feminist movement? 2. How did Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party aim to establish respect for women and their art? 3. What is a “femmage” according to Miriam Schapiro? 4. How does Cindy Sherman challenge the “male gaze” in her work? 5. How does Barbara Kruger attempt to subvert and expose the messages of mass media? 6. Why did Ana Mendieta seek a spiritual connection with nature? 7. What was Hannah Wilke’s ultimate hope in creating a piece such as Starification Object Series? 8. How did Kiki Smith’s Untitled address concerns over the control of one’s body? 9. Why does Faith Ringgold primarily use fabric as her medium? How does Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima combine both personal and political issues? 10. How does Adriana Piper hope to effect social change with her work? 11. Explain how the hair styles in Lorna Simpson’s work Stereo Styles comment on racial differences? 12. How does Melvin Edwards explore what lynching means “metaphorically or symbolically?” 13. In what ways does the viewer interact with an installation like David Hammon’s Public Enemy? 14. What about Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s work is reminiscent of Rauschenberg’s combines? 15. What techniques did Leon Golub use in Mercenaries (IV) to give the viewer a sense of being in peril? 16. How are fiber materials symbolic for Magalena Abakanowicz? What type of mood is suggested in Backs? 17. -

Contemporary Art and Student Learning

The International Journal of Arts Education Contemporary Art Contemporary Art and Student and Student Learning Learning Michael Day Professor Emeritus The Brigham Young University E-mail:[email protected] Abstract Three broad rationales for art education are reviewed: Creative self-expression; history and culture, and popular visual culture. All are considered praiseworthy as bases for art curriculum, or as components within art programs. Values of contemporary art are viewed as essential for student learning, regardless of selected rationale or combination of rationales. Several contemporary artists are presented and discussed as exemplars for student learning, including artists from several regions of the world. Six typical contributions of contemporary artists are discussed with reference to potential student learning. Key Words: rationales for art education, contemporary art, student learning art curriculum This article is based on a presentation given at the World Creativity Summit Taipei held in June 2008. C InJAE7.1 ○ NTAEC 2009 125 國際藝術教育學刊 Contemporary Art The content of art education in many countries, including the United and Student Learning States, addresses several broad categories. Children and young people in the schools make art through use of traditional art materials and art principles and conventions. They study the history of art from their own culture and from cultures around the world, with attention to significant works and major artists from various periods and styles. Currently much attention is focused on the study of visual culture from the mass media and advertising that students experience in their everyday lives. Any of these three basic approaches or combinations of them can lead to quality art programs, as attested by examples of excellence in art education from around the world. -

Chapter 31 Contemporary Art Worldwide the End of the Century: a Messy Ride

Chapter 31 Contemporary Art Worldwide The End of the Century: A Messy Ride The final 30 years of the 20th century saw artistic expression taking ever more diverse forms. • difficult to identify movements clearly, as artists feel free to move from one form of expression to another. • sometimes difficult to identify the art per se, as post- modernism sometimes meant that the artistic creation ppyrocess led to art that existed only for a brief moment in time… Kruger’s work often combines text and image in an ironic fashion. •Many artists who have embraced the postmodern •They were interested in investigggating the dynamics of power and privilege •They focused on issues of gender and sexuality in the contemporary world. Untitled (We Will No Longer Be Seen and Not Heard) •Kruger’s works frequently involve criticism of the habits imposed on women by society, and of the negative impact of men running the world… her work evolved from being specifically feminist to being critical of society’s norms in all areas •Artist began as a graphic designer for Mademoiselle magazine •Words placed in large photos as de ign e lements, an d to hig hlig ht a message •Artistic message often relies on irony BARBARA KRUGER, Your gaze hits the side of my face Social Art: Race, Ethnicity, and National Iden ti ty Faith Ringgold, Who’s Afraid Melvin Edwards, Tambo, 1993 of Aunt Jemima? 1983 •It is a quilt, a medium that is associated with women •Welded sculpture of chains, spikes, knife •Tribute to her mother but also blades, and other found objects that allude addresses African American culture to the lynching of African Americans and and the struggles of women to the continuing struggle for civil rights and overcome oppression an end to racism. -

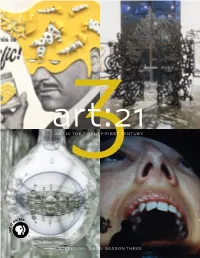

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season Three

art:21 ART IN3 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON THREE SEASON THREE GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Three of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Critical Vehicles

wodicz cover 09/13/01 2:53 PM Page 1 Krzysztof Wodiczko, one of the most original avant-garde Critical Vehicles Writings, Projects, Interviews Wodiczko artists of our time, is perhaps best known for the politically Krzysztof Wodiczko charged images he has projected onto buildings and monu- Krzysztof Wodiczko ments from New York to Warsaw—images of rockets projected onto triumphal arches, the image of handcuffed wrists pro- jected onto a courthouse facade, images of homeless people in bandages and wheelchairs projected onto statues in a park from which they have been evicted. In projects such as the Homeless Vehicle, which he designed through discussions with homeless people, Wodiczko has helped to make public space a place where marginalized people can speak, establish their presence, and assert their rights. Critical Vehicles is the first book in English to collect Wodiczko’s own writings on his projects. Wodiczko has stated that his principal artistic concern is the displacement of tradi- tional notions of community and identity in the face of rapidly expanding technologies and cultural miscommunication. In Critical Vehicles these writings he addresses such issues as urbanism, homeless- ness, immigration, alienation, and the plight of refugees. Fusing wit and sophisticated political insight, he offers the artistic means to help heal the damages of uprootedness and other contemporary troubles. In 1998, Krzysztof Wodiczko was awarded the Hiroshima Prize for his contribution as an artist to world peace. “Krzysztof Wodiczko’s public artworks bring the city to life. Statues, monuments, and buildings speak, questioning power and even declaring rights. The writings in Critical Vehicles place this poetic, disquieting art within the most urgent polit- ical project of our time: the struggle to extend democracy by interrupting certitudes about the meaning of social life. -

History of New Media Art Fridays, 3:10Pm-6:10Pm 205 Richmond, Room 7320

Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies Fall 2014 VISM 2B09 - History of New Media Art Fridays, 3:10pm-6:10pm 205 Richmond, Room 7320 Dave Colangelo, [email protected] Office Hours & Location: Fridays, 1pm-2pm or by appointment, Room 325 Credit Value: 0.5 Pre-requisites: 3.0 credits of first-year studio and 1.0 credit of first-year liberal studies, including the first year writing course with a minimum passing grade of 60%, and an overall average of 60%. Anti-requisite: Students who have taken VISC 2B09 may not take this course for further credit. COURSE CALENDAR DESCRIPTION: This survey course offers a history of the relationship of art and media from the beginnings of photography and avant-garde cinema to contemporary digital and video art practices. The course examines technological developments that have affected and transformed perception and representation including time-motion studies, industrialization (Taylorism), mass culture, and global electronic networks (Internet). The influence of new media on various avant-garde movements including cubism, constructivism, surrealism, dada, and on the stylistic innovations of collage and montage will be explored. Selected writings on art and technology by key thinkers of the twentieth century will complement a visual and intellectual survey of artworks. REQUIRED TEXTBOOKS/COURSE PACKS: Textbooks: Available for purchase from the OCAD bookstore (51 McCaul Street) - Michael Rush: New Media in Art (second edition). Thames & Hudson, 2005. - Mark Tribe/Reena Jana (eds.): New Media Art. Taschen, 2006. (also available online as an open source book at https://wiki.brown.edu/confluence/display/MarkTribe/New+Media+Art) R: Course Reader: Available for purchase from the OCAD bookstore: C: Canvas A number of readings are available as pdf’s on Canvas under “Files” LEARNING OUTCOMES: Upon completing this course, students will have: 1. -

Download The

MESSAGES TO THE PUBLIC: KRZYSZTOF WODICZKO AND JENNY HOLZER VS. THE REAGAN REVOLUTION by Vanessa Nicole Sorenson B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Fine Arts) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2010 © Vanessa Nicole Sorenson, 2010 Abstract In the week preceding the 1984 United States presidential election, Jenny Holzer and Krzysztof Wodiczko presented ephemeral works of art in public spaces in Manhattan that addressed the election and were highly critical of President Ronald Reagan. Previous considerations of Wodiczko’s AT&T projection, Holzer’s Sign on a Truck and the larger public art movement of that time have emphasized a post-structuralist interpretation, neglecting the applied political aspects in favour of their theoretical underpinnings. With a move towards the practical aspects of the works, this thesis examines the conditions that led to the presentation of these two works and considers what they can teach us about the larger practice of political public art during that period in New York. Chapter 1 considers the political, economic and artistic context of the United States—and New York in particular—in the early to mid 1980s. The Chapter 2 offers an analysis of Wodiczko’s AT&T projection, a night-time projection of the image of President Reagan’s French-cuffed hand onto the side of the AT&T Long Lines building, posed for a recognizable American ritual, the Pledge of Allegiance. Chapter 3 closely considers Sign on a Truck, for which Jenny Holzer deployed a giant screen, mounted on the side of an 18-wheeler truck, to display pre-recorded videos created by collaborating artists interspersed with “man-on-the-street” interviews commenting on the looming presidential election.