The Synagogue As Foe in Early Christian Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview

St. John’s Lutheran Church, Adult Education Series, Spring 2019 “The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview A. The Four Gospels – Greek, euangelion, “good news,” Old English, god-spel “Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31) 1. Mark a. author likely John Mark, cousin of Barnabas (Col 4:10), companion of Peter (Acts 12:12) and Paul (Acts 12:12, 15:37-38) b. written ca 50-65 AD, perhaps after death of Peter c. likely written to Gentile Christians in Rome d. focus on Jesus as the Son of God 2. Matthew a. author likely Matthew (Levi), one of the Twelve Apostles b. written ca 60-70 AD c. likely written to Jewish Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Messiah 3. Luke a. author likely Luke, physician, companion of Paul (Col 4:14), author of Acts, gives an orderly account (1:1-4) b. written ca 60-70 AD c. addressed to Theophilus (Greek, “lover of God”), Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Savior of all people 4. John a. author possibly John, one of the Twelve Apostles – identifies himself as the “beloved disciple” (John 21:20) b. written ca 80-100 AD c. addressed to Jewish and Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as God incarnate 1 St. -

Ecclesia & Synagoga

Ecclesia & Synagoga: then and now These images tell us something about the Today there is a move to redeem such images impact of art and image on our life of faith, to reflect the healing that has taken place in including our approach to Scripture. the relationship between Christians and Jews Depicted in these sculptures is the Church’s over the past fifty years since the Second journey out of its antisemitic past into a new Vatican Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate. era of respect and reconciliation with the The image above right shows a sculpture Jewish people. The two figures represent commissioned by St Joseph’s University, Ecclesia and Synagoga, church and Philadelphia.2 Here Synagoga and Ecclesia sit synagogue. Note the differences between the side by side, turned toward each other in artworks. friendship and as equal partners in a position The figures pictured above left are from the that suggests the chevruta method of Torah Cathedral in Strausbourg1 and are typical of study, one holding the Torah scroll, the other those which appeared repeatedly in church the Christian Bible. A miniature of this statue architecture and manuscripts of the Middle was presented to Pope Francis at the 2015 Ages. Lady Ecclesia is upright, regal, Annual Conference of the International victorious, holding a cross and the Christian Council of Christians and Jews held in Rome Scriptures. By contrast, Lady Synagoga is for the 50th Anniversary of Nostra Aetate. downcast, blindfolded, dishevelled, holding a Pope Francis himself blessed the original broken staff, the tablets of the Jewish Law artwork on his 2015 visit to the USA. -

GRADES 4/5 Supplemental Scripture Parables in the Gospel of Matthew

Catholic Arts & Academic Competition Catholic Heroes GRADES 4/5 Supplemental Scripture Parables in the Gospel of Matthew Lamp under a bushel 5:14-15 14 “You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid. 15 No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house. Wise and foolish builders 7:24-27 24 “Everyone then who hears these words of mine and acts on them will be like a wise man who built his house on rock. 25 The rain fell, the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on rock. 26 And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them will be like a foolish man who built his house on sand. 27 The rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell—and great was its fall!” Sower and four types of soil 13:3-8, 18-23 3 And he told them many things in parables, saying: “Listen! A sower went out to sow. 4 And as he sowed, some seeds fell on the path, and the birds came and ate them up. 5 Other seeds fell on rocky ground, where they did not have much soil, and they sprang up quickly, since they had no depth of soil. 6 But when the sun rose, they were scorched; and since they had no root, they withered away. -

1 1 Thessalonians 5: 1-11, Matthew 25: 14-30 Olivet

1 Thessalonians 5: 1-11, Matthew 25: 14-30 Olivet Church, Charlottesville --- November 19, 2017 We Belong to the Day We are tempted to treat Jesus’ parables as allegories, with the characters and events in the stories representing God, historical figures, and events. But the harshness of the master in today’s parable discourages us from making a correlation between him and God or Jesus, and reminds us that these stories are not allegories. And there are those who use Jesus’ teachings about the end-time, when he returns to judge the world and usher in the fullness of God’s kingdom, to instill fear in people that they might return to God and God’s way. But the fact that the servant who was judged harshly, and thrown into outer darkness, had acted out of fear should discourage us from using the threat of judgement to instill faith and discipleship. The Parable of the Talents is part of Jesus' discourse with his disciples about enduring through difficult times while living in anticipation of his return. It recalls the parable of the faithful and wise slave in chapter 24, who, although the master is delayed, continues to do the work of the master until the master returns to find him doing the tasks that have been appointed to him in the master's absence. A remarkable element of the Parable of the Talents is the amount of wealth that is entrusted to each servant. A talent, a certain weight of precious metal, was equal to about 6,000 denarii. Since one denarius was a common laborer's daily wage, a talent would be roughly equivalent to 20 years of wages. -

Table of Contents Explanation of Lectio Divina

Lectio Divina for the Retreat Feb 2021 The Gospel of Mark – In the Year of Mark All the following passages are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition of the Bible (NRSVCE). This is the version that is used in the Canadian Lectionary (the readings we hear at mass on the weekdays and on Sunday.). The reason I chose this version is so that we would be familiar with this version and when we listen to the Gospel being proclaimed, we can have a connection to its proclamation. We will not have time to walk through the Gospel of Mark in its entirety, but in a chronological walk through, life some major themes. I have included the paragraph titles following the readings, so that we can have a bird’s eye view of the development of the Gospel. St. Mark is particular in the order he presents the events of Jesus’ life. He does this to emphasize that Jesus’ Journey from the beginning of His ministry is always moving toward Jerusalem to accomplish what He was sent to do, save humanity by becoming the sacrificial Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world through His passion, death and resurrection. Try to read the passages before attending the live stream ‘Lectio Divina’ and allow the Word of God to speak to your soul. If at all possible, avoid printing the pages to save on paper. You can use a journal to write down words or phrases that remain with you and the that Lord is speaking to you. -

The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus Super Psalmos

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos Ellen Scully Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Ellen, "The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 95. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/95 THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS by Ellen Scully A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABTRACT THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS Ellen Scully Marquette University, 2011 In this dissertation, I focus on the soteriological understanding of the fourth- century theologian Hilary of Poitiers as manifested in his underappreciated Tractatus super Psalmos . Hilary offers an understanding of salvation in which Christ saves humanity by assuming every single person into his body in the incarnation. My dissertation contributes to scholarship on Hilary in two ways. First, I demonstrate that Hilary’s teaching concerning Christ’s assumption of all humanity is a unique development of Latin sources. Because of his understanding of Christ’s assumption of all humanity, Hilary, along with several Greek fathers, has been accused of heterodoxy resulting from Greek Platonic influence. I demonstrate that Hilary is not influenced by Platonism; rather, though his redemption model is unique among the early Latin fathers, he derives his theology from a combination of Latin-influenced biblical exegesis and classical Roman themes. -

Ecclesia Et Synagoga 50 Years Ago and Today

Ecclesia Et Synagoga 50 Years Ago and Today Temple B’nai Shalom Braintree, Massachusetts October 3, 2015 Rabbi Van Lanckton Fifty years ago this month, on October 29, 1965, a front page story in the New York Times carried this headline: POPE PAUL PROMULGATES FIVE COUNCIL DOCUMENTS, ONE ABSOLVING THE JEWS. The story began, “Pope Paul VI formally promulgated as church teaching today five documents embodying significant changes in Roman Catholic policies and structures and offering friendship and respect to other world religions.” One of the documents was a declaration “on the relation of the church to non- Christian religions. The declaration includes the dissociation of the Jewish people in Catholic doctrine from any collective responsibility for the Crucifixion of Christ and an injunction to all Catholics against depiction of the Jews as ‘rejected by God or accursed.’” I remember that day fifty years ago. I was then starting my second year as a student at Harvard Law School. I lived in Cambridge with two roommates, Jon and Harvey, both of them Jewish. As we left our apartment that morning to walk to class, Jon said, with his usual humor, “I feel so much better. Now I can walk a little taller.” At some level Jon was kidding. We did not think that Jews living in 1965 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, or for that matter anywhere in the world, had any responsibility for the Romans who crucified Jesus in the First Century. But Jon also was not kidding. As I learned more about Judaism, and certainly by the time I converted to Judaism about 18 months later, I knew that the ancient libel against all Jews that we killed Jesus resulted in centuries of discrimination and persecution: the Crusades, the Inquisition, pogroms and the Holocaust in Europe and beyond, and even in America restrictive covenants and agreements that excluded Jews from some neighborhoods and jobs and entire professions. -

Antisemitism – Medieval Activity

MEDIEVAL ANITISEMITISM ACTIVITY This activity is designed to enable students to examine multiple historical documents related to the discrimination and persecution of Jews during the Middle Ages (primary and secondary sources, text and visual), to respond to a series of questions and to share their work with their peers. Procedure: This activity can be conducted as either an individual, paired or group exercise. After the students have been assigned their topic(s) and given their documents, they should complete the exercise. Each of the 9 documents (text and visual) has a series of specific questions for the document. In addition there are two generic questions: • What is your reaction to the text and images? • Which historical root(s) of antisemitism are revealed in this documents? Students should write their responses in the space provided on the question sheet. Report out. After the students have had a chance to complete their specific task, they should share their responses with the rest of the class. Depending upon the number of students assigned to each topic and the time allotted for this activity, it could be a Think-Pair-Share strategy, or a modified Jigsaw Cooperative Learning strategy. After all have shared their responses, you should ask the students to identify the themes that intertwine to characterize antisemitism in the Middle Ages. List of Documents 1. Ecclesia and Synagoga 2. Crusades 3. Lateran Council of 1215 4. Expulsions from Western and Central Europe 5. Judensau 6. Blood Libel 7. Jewish Quarter or Ghetto 8. Moneylenders and Usurers 9. The Black Death B-1 Ecclesia and Synagoga Ecclesia and Synagoga above the portico of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris (c. -

Martyrdom As a Spiritual Test in the Luciferian Libellus Precum

Nonne gratum habere debuerunt: Martyrdom as a Spiritual Test in the Luciferian Libellus Precum One of the many ways in which Christians throughout antiquity defined themselves in relation to Jews and pagans was the special role that martyrs played in the Christian tradition.1 Ironically, in the fourth century martyrdom frequently served to draw boundaries not between Christians and Jews or pagans, but between different groups of Christians. Christians readily adapted their old mental frameworks to fit the new circumstances of an empire supportive of Christianity. This process is most clearly apparent with regard to one such group, the Luciferians. No scholar has yet pointed out how the Luciferians construct their group’s history by who persecutes and who is persecuted. Their unique emphasis on martyrdom as a spiritual test has also escaped notice. Although in many respects these are typical behaviors for late antique Christians, the Luciferians offer a great – and overlooked – example of a schismatic group developing a separate identity from these same, typical behaviors. This schismatic group developed after a disciplinary dispute. The Council of Alexandria was called in 362 to decide if a group of bishops who had signed the “Sirmian Creed” at the Council of Rimini should be allowed to return to the Church and retain their clerical rank – bishops remaining bishops, deacons remaining deacons, and so on.2 They agreed to this. A small group of Christians, however, disagreed with the decision of the council. Lucifer of Cagliari, an exiled bishop who had expressed dissatisfaction with the council, probably led this group. They called the bishops who had sworn to the Arian creed “praevaricatores” (‘traitors’), much like the Donatists called their enemies “traditores.” They refused to hold communion with most other bishops of the Church, because those bishops held communion with these praevaricatores. -

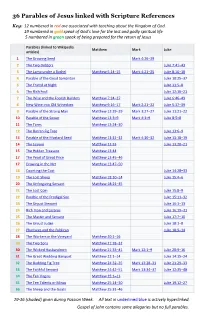

36 Parables of Jesus Linked with Scripture References

36 Parables of Jesus linked with Scripture References Key: 12 numbered in red are associated with teaching about the Kingdom of God 19 numbered in gold speak of God’s love for the lost and godly spiritual life 5 numbered in green speak of being prepared for the return of Jesus Parables (linked to Wikipedia Matthew Mark Luke articles) 1 The Growing Seed Mark 4:26–29 2 The Two Debtors Luke 7:41–43 3 The Lamp under a Bushel Matthew 5:14–15 Mark 4:21–25 Luke 8:16–18 4 Parable of the Good Samaritan Luke 10:25–37 5 The Friend at Night Luke 11:5–8 6 The Rich Fool Luke 12:16–21 7 The Wise and the Foolish Builders Matthew 7:24–27 Luke 6:46–49 8 New Wine into Old Wineskins Matthew 9:16–17 Mark 2:21–22 Luke 5:37–39 9 Parable of the Strong Man Matthew 12:29–29 Mark 3:27–27 Luke 11:21–22 10 Parable of the Sower Matthew 13:3–9 Mark 4:3–9 Luke 8:5–8 11 The Tares Matthew 13:24–30 12 The Barren Fig Tree Luke 13:6–9 13 Parable of the Mustard Seed Matthew 13:31–32 Mark 4:30–32 Luke 13:18–19 14 The Leaven Matthew 13:33 Luke 13:20 21 – 15 The Hidden Treasure Matthew 13:44 17 The Pearl of Great Price Matthew 13:45–46 17 Drawing in the Net Matthew 13:47–50 18 Counting the Cost Luke 14:28–33 19 The Lost Sheep Matthew 18:10–14 Luke 15:4–6 20 The Unforgiving Servant Matthew 18:21–35 21 The Lost Coin Luke 15:8–9 22 Parable of the Prodigal Son Luke 15:11–32 23 The Unjust Steward Luke 16:1–13 24 Rich man and Lazarus Luke 16:19–31 25 The Master and Servant Luke 17:7–10 26 The Unjust Judge Luke 18:1–8 27 Pharisees and the Publican Luke 18:9–14 28 The Workers in the Vineyard Matthew 20:1–16 29 The Two Sons Matthew 21:28–32 30 The Wicked Husbandmen Matthew 21:33–41 Mark 12:1–9 Luke 20:9–16 31 The Great Wedding Banquet Matthew 22:1–14 Luke 14:15–24 32 The Budding Fig Tree Matthew 24:32–35 Mark 13:28–31 Luke 21:29–33 33 The Faithful Servant Matthew 24:42–51 Mark 13:34–37 Luke 12:35–48 34 The Ten Virgins Matthew 25:1–13 35 The Ten Talents or Minas Matthew 25:14–30 Luke 19:12–27 36 The Sheep and the Goats Matthew 25:31 46 – 29-36 (shaded) given during Passion Week. -

Ὁ Ὤν Εὐλογητὸς Χριστὸς Ὁ Θεὸς Ἡμῶν: Observations on the Early Christian Interpretation of the Burning Bush Scene

Ὁ ὤν εὐλογητὸς Χριστὸς ὁ Θεὸς ἡμῶν: OBSERVATIONS ON THE EARLY CHRISTIAN INTERPRETATION OF THE BURNING BUSH SCENE Bogdan G. Bucur Duquesne University [email protected] Résumé Un aperçu des productions exégétiques, doctrinales, hymnogra- phiques et iconographiques dans la riche histoire de la réception d’Exode 3 au cours du premier millénaire de notre ère conduit à la conclusion que la lecture chrétienne la plus ancienne, la plus répan- due et la plus constante de ce texte a été son interprétation comme manifestation du Logos incarnaturum, comme « Christophanie ». Les termes couramment utilisés dans la littérature savante pour rendre compte de cette approche exégétique sont insatisfaisants, car ils ne parviennent pas à saisir la dimension épiphanique du texte, tel qu’il a été lu par de nombreux exégètes chrétiens anciens. Cet article examine aussi – et rejette – la proposition récente d’évaluer la relation directe entre le Christ et le Ὁ ὤν d’Exode 3,14 comme un exemple de la « Bible réécrite ». Summary A survey of the exegetical, doctrinal, hymnographic, and icono- graphic productions illustrating the rich reception history of Exodus 3 during the first millennium CE leads to the conclusion that the earliest, most widespread and enduring Christian reading of this text was its interpretation as a manifestation of the Logos-to- be-incarnate: a “Christophany”. The terms currently employed in scholarship to account for this exegetical approach are unsatisfactory because they fail to capture the epiphanic dimension of the text as Judaïsme ancien / Ancient Judaism 6 (2018), p. 37-82 © FHG 10.1484/J.JAAJ.5.116609 38 BOGdaN G. -

B I G M E a N I

LITTLE STORIES with B I G M E A N I N G Parables in Poetic Form by Shirley May Davis Copyright c January 2003 by Shirley May Davis TABLE of CONTENTS Index ..................................................................... 3 Lamp Light .......................................................... 5 The Difference ................................................... 6 New Versus Old ................................................. 7 Heart Condition .................................................. 8 Small Beginnings .................................................9 Wheat or Weeds .................................................10 Heaven Like Leaven ..........................................11 Treasure Without Measure ..............................11 Pearl Seeker .........................................................12 Fish - In or Out ................................................... 12 Lost and Found ................................................... 13 Importance of Forgiveness .............................14 Penny Paycheque ...............................................15 To Go or Not To Go ..........................................16 To Feast or Not To Feast .................................17 Vengeance in the Vineyard .............................18 Little or Much ................................................... 19 Ready or Not, Here I Come..............................20 Wise or Foolish .................................................. 21 Neighbourliness .................................................. 22 Unwise Decision