Archive of Darkness William Kentridge’S Black Box/Chambre Noire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts and Culture Unnumbered Sparks: Janet Echelman, TED Sculpture Foreword

Arts and Culture Unnumbered Sparks: Janet Echelman, TED Sculpture Foreword Imagine a world without performing or visual arts. Imagine – no opera houses, no theatres or concert halls, no galleries or museums, no dance, music, theatre, collaborative arts or circus – and in an instant we appreciate the essential, colourful, emotive and inspiring place that creative pursuits hold in our daily life. Creating opportunities for arts to flourish is vital, and this includes realising inspiring venues which are cutting edge, beautiful, functional, sustainable, have the right balance of architecture, acoustics, theatrical and visual functionality and most importantly are magnets for artists and audiences, are enjoyable spaces and places, and allow the shows and exhibitions to go on. 4 Performing Arts Bendigo Art Gallery 5 Performing Arts Arts and Culture Performing and Visual Arts 03 08 – 87 88 – 105 Foreword Performing Musicians, Arts Artists, Sculptors and Festivals 106 – 139 140 – 143 144 Visual Arup Services Photography Arts Clients and Credits Collaborators Contents Foreword 3 Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall 46 Singapore South Bank Studio, Queensland Symphony Orchestra 50 Australia Performing Marina Bay Sands Theatres 52 Arts 8 Singapore Elisabeth Murdoch Hall Federation Concert Hall 56 Melbourne Recital Centre 10 Australia Australia Chatswood Civic Place 58 Sydney Opera House 14 Australia Australia Carriageworks 60 Glasshouse Arts, Conference and Australia Entertainment Centre 16 Australia Greening the Arts Portfolio 64 Australia Melbourne -

Flying Over the Abyss Η Υπερβαση Τησ Αβυσσοσ

FLYING OVER THE ABYSS Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΒΥΣΣΟΣ 7 NOVEMBER 2015 – 29 FEBRUARY 2016 CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI - STATE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART FLYING OVER THE ABYSS Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΒΥΣΣΟΣ CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI Tuesday - Wednesday - Thursday - Saturday - Sunday 10:00-18:00 Friday 10:00-22:00 Monday Closed All works exhibited are courtesy of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection. Our warmest thanks to the D.Daskalopoulos Collection and Nikos Kazantzakis Museum for their generous loans to the exhibition. Marina Abramović Alexis Akrithakis Matthew Barney Hans Bellmer Lynda Benglis John Bock Louise Bourgeois Heidi Bucher Helen Chadwick Savvas Christodoulides Abraham Cruzvillegas Robert Gober Asta Gröting Jim Hodges Jenny Holzer Kostas Ioannidis Mike Kelley William Kentridge Martin Kippenberger Sophia Kosmaoglou Sherrie Levine Stathis Logothetis Ana Mendieta Maro Michalakakos Doris Salcedo Kiki Smith Costas Tsoclis Mark Wallinger CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI Suggested exhibition route according to room numbering Ground floor 1st floor ROOM 2 ROOM 1 ROOM 2 ROOM 3 ROOM 4 ROOM 5 ROOM 2 Tracing a human being’s natural course from life to death, the exhibition Flying over the Abyss follows, in a way, the flow of the universal text of The Saviors of God by that great Cretan, Nikos FLYING OVER Kazantzakis. It neither illustrates, nor narrates. The text, concretely actual and precious, in its original manuscript, does remain complete in its roundness and maximum in its creative artistry. THE ABYSS Unravelled comes along the harrowing of the other, not alienated, yet refreshing moments of the Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ contemporary artistic creation. In the exhibition, works by Greek and international artists share in, pointing out the trauma of birth, the luminous interval of life and creativity, and death. -

PDF Press Release

P R E S S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 4, 2008 Williams College Museum of Art Presents William Kentridge Prints February 9 – April 27, 2008 and June 21 – August 24, 2008 and History of the Main Complaint, 1996 February 2–April 27, 2008 Williamstown, MA—The Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) presents William Kentridge Prints, the first of a two-part exhibition, which features 120 works by this pioneering South-African artist. WCMA will also be showing Kentridge's film History of the Main Complaint, 1996, in the museum's media field gallery. Okwui Enwezor, Dean of Academic Affairs at San Francisco Art Institute and Adjunct Curator at International Center of Photography, New York, will give a lecture entitled "(Un) Civil Engineering: William Kentridge's Allegorical Landscapes" on Saturday, April 12 at 2:00 pm in Brooks -Rogers Recital Hall at Williams College. This is a free public program and all are invited to attend. William Kentridge Prints represents over a third of the out put in the medium of printmaking for Kentridge, who works in the tradition of socially and politically engaged artists such as William Hogarth, Francisco Goya, Honore Daumier, and Kathe Kollwitz. Kentridge's work reflects on the human condition, specifically the history of apartheid in his own country and the ways in which our personal and collective histories are intertwined. The work in this exhibition ranges from 1976 to 2004 and includes aquatint, drypoint, engraving, etching, monoprint, 15 LAWRENCE HALL DRIVE SUITE 2 WILLIAMSTOWN MASSACHUSETTS 01267-2566 telephone 413.597.2429 facsimile 413.458.9017 web WWW.WCMA.ORG linocut, lithograph, and silkscreen techniques, often in combinations. -

Exhibition Brochure

SKELETONS OF WAR EXHIBITION CHECKLIST Many of the works in this exhibition were inspired by the horrors experienced by SCIENCE & MEDICINE THE COMING OF DEATH soldiers and civilians in war-torn regions. World War I, among the most devastating conflicts, 1. “The Skeletal System,” from Andrew Combe, M.D., 9. Artist unknown (German), Horsemen of the The Principles of Physiology applied to the Apocalypse, sixteenth century, woodblock, left Europe and its people broken and Preservation of Health, and to the improvement of 3 x 2 ½ in. (7.6 x 6.4 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, changed. Reeling from the horrors Physical and Mental Education (New York: Harper 1983.5.82.c BONES and Brothers, 1836), Dickinson College Archives and they experienced, artists reacted in Special Collections. 10. Circle of Albrecht Dürer, Horsemen of the Representing the Macabre Apocalypse, sixteenth century, woodblock, 3 x 3 in. varying ways. During the decades 2. Abraham Blooteling, View of the Muscles and Tendons (7.6 x 7.6 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, 1983.5.83.d following the war, expressionism of the Forearm of the Left Hand, plate 68 from Govard Bidloo, Anatomi humani corporis centum et 11. Artist unknown, Apocalyptic Vision, sixteenth reached its peak in dark, emotionally- quinque tabulis (Amsterdam: Joannes van Someren, century, woodblock, 2 x 2 3/8 in. March 5–April 18, 2015 1685), engraving and etching, 16 5/8 x 13 in. (47.3 x 33 (5.1 x 6 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, 1983.5.79.a charged artworks, as in the suite of cm). -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

Art As a Catalyst to Activate Public Space: the Experience of 'Triumphs

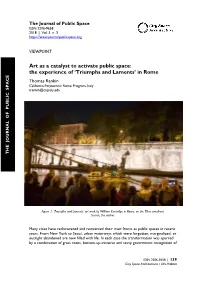

The Journal of Public Space ISSN 2206-9658 2018 | Vol. 3 n. 3 https://www.journalpublicspace.org VIEWPOINT Art as a catalyst to activate public space: the experience of ‘Triumphs and Laments’ in Rome Thomas Rankin California Polytechnic Rome Program, Italy [email protected] THE JOURNAL OF PUBLIC SPACE THE JOURNAL Figure 1. ‘Triumphs and Laments’ art work by William Kentridge in Rome, on the Tiber riverfront. Source: the author. Many cities have rediscovered and reinvented their river fronts as public spaces in recent years. From New York to Seoul, urban waterways which were forgotten, marginalized, or outright abandoned are now filled with life. In each case the transformation was spurred by a combination of grass roots, bottom-up initiative and savvy government recognition of ISSN 2206-9658 | 139 City Space Architecture / UN-Habitat Art as a catalyst to activate public space the projects’ potentials. Once the city leaders embraced the projects - and not a moment sooner - public and private funding materialized and bureaucratic barriers disappeared. In Rome, whether due to the complexity of the chain of responsibility for the river front, or simply an ingrained aversion to progressive planning - saying no or saying nothing is much easier than taking responsibility for positive change - initiatives to renew the urban riverfront have been small and disconnected. Diverse interests ranging from green space to water transit, from river front commerce to ecological restoration, have all vied for a role in the river’s regeneration. But one particular discipline, that of art, has succeeded more than others in attracting international attention and changing the way people in Rome and throughout the (art) world see the Tiber. -

William Kentridge Five Themes 29 June – 5 September 2010 Invisible Mending, from the Installation 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003

# 68 Concorde William Kentridge Five Themes 29 June – 5 September 2010 Invisible Mending, from the installation 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003 South African artist William Kentridge (born between them, shifting from theatre to drawing 1955) first achieved international recognition or from drawing to film. Though his work in the 1990s with a series of what he called resonates with the South African experience, “drawings for projection”: short animated films Kentridge also draws on varied European based on everyday life under apartheid. Since sources, including literature, opera, theatre and then, Kentridge has widened his thematic range, early cinema, to create a complex universe expanding beyond his immediate environment where good and evil are complementary and to examine other political conflicts. His oeuvre inseparable forces. charts a universal history of war and revolution, An important conceptual development in evoking the complexities and tensions of Kentridge’s practice of recent years is the artist’s postcolonial memory and imaging the residual self-reflexive yet playful focus on his relationship traces of devastating policies and regimes. to the world. Whereas the early charcoal The first retrospective in France devoted to the animations operated with a cast of fictional artist is centred on the broad themes that have characters, Kentridge himself now appears as motivated Kentridge during his career, through the principal character in his own creations. By a large choice of works dating from the late referencing optical illusion and the mechanics 1980s to today. While putting the accent on of perception, in his latest works, Kentridge recent pieces, it highlights the broad scope moves beyond the characteristic manipulations of Kentridge’s artistic practice and diversity of animation to create a world conceived as a of media, including drawing, film, collage, theatre of memory. -

24-25 June 2016 Conveners: Emma Dillon, Ziad Elmarsafy, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes

1 The Musical Pasts Consortium I Music and the Urban King’s College London: 24-25 June 2016 Conveners: Emma Dillon, Ziad Elmarsafy, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes FRIDAY 24 JUNE (THE ANATOMY MUSEUM, KING’S COLLEGE LONDON, STRAND CAMPUS) SESSION 1 (9:30-12:30) Introductory (Chair: James Chandler) Discussion of pre-circulated reading (Emma Dillon, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes): David Harvey Rebel Cities (Verso, 2013), pp. 115-53 Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World (Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 241-49 and pp. 283-321 David Wallace, Europe: A Literary History, 1348-1418 (Oxford University Press), vol. 1, pp. xxvii-xlii Coffee (10:45-11:15) Discussion 1 (Chair: Gary Tomlinson) Martha Feldman: A sound recording (remastered) of the castrato Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922) singing Paolo Tosti’s song “Ideale” for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company Ltd, recorded in Rome in April 1902. (see attachment) Katherine Schofield: “Shruti-vina”, sent from Calcutta by Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore to be exhibited at the 1886 Colonial and India Exhibition in London, and thence donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1890. (see attachment) Michael Denning: A son pregón, “El Manisero,” recorded by the Havana son trio, Trio Matamoros, in New York in July 1929 (Victor 46401, released in Accra and Lagos in 1933 as HMV GV 3), “that deplorable rhumba” (Jorge Luis Borges), a stylization of an urban street vendor’s cry (the peanut vendor). Source: The Legendary Trio Matamoros, Tumbao TCD-016, 1992. (see attachment) Lunch (12:30-2:00) 2 SESSION 2 (2:00-5:30) Discussion 2 (Chair: Flora Willson) Mary Ann Smart: A passage taken from the book Viaggio a Londra, part of a six- volume series of travel guides published in Bologna in 1837. -

William Kentridge Thick Time 21 September - 15 January 2017 Large Print Labels and Interpretation Gallery 1

William Kentridge Thick Time 21 September - 15 January 2017 Large print labels and interpretation Gallery 1 1 Left of gallery door: William Kentridge Thick Time William Kentridge (b.1955) lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa. This exhibition takes a journey through a series of environments he created between 2003 and 2016. His work spans drawing and printmaking, film, performance, dance, music, tapestry and sculpture. Kentridge’s expressionist drawings stand in a tradition of radical figuration from Francisco de Goya in the 19th century to Max Beckmann, George Grosz or Käthe Kollwitz in the early 20th century. His great skill as a draughtsman combines with his interest in early cinema and in theatre. (continues on next page) 2 The experience of studying radical mime and acting techniques at L’École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris and being part of an experimental theatre group in Johannesburg in the late 1970s and 1980s has been a major influence. Kentridge often collaborates with composers, dancers, musicians, puppeteers and designers; and has directed a number of operas. Six immersive installations are located over two floors of the museum. The themes in Kentridge’s work emerge from his experience of apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa and his reflections on colonialism and exile. The works also show his fascination with the utopian aspirations of early Modernism; the science and politics of time and space; the beauty and fragility of the natural world; and the nature of creativity. 3 Right side of gallery door: Untitled (Bicycle Wheel II) n/a 2012 Steel, timber, brass, aluminium, bicycle parts and found objects Courtesy William Kentridge; Marian Goodman Gallery (New York/Paris/London); Goodman Gallery (Johannesburga and Cape Town); Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan) 4 Left of gallery, clockwise: WILLIAM KENTRIDGE: THICK TIME This gallery presents three installations. -

Portraits As Objects Within Seventeenth-Century Dutch Vanitas Still Life

University of Amsterdam Graduate school of Humanities – Faculty of Humanities Arts and Culture – Dutch Art (Masters) Author: Rukshana Edwards Supervisor: Dr. E.E. P. Kolfin Second reader: Dr. A.A. Witte Language: English Date: December 1, 2015 Portraits as Objects within Seventeenth-Century Dutch Vanitas Still Life Abstract This paper is mainly concerned with the seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas still life with special attention given to its later years in 1650 – 1700. In the early period, there was significant innovation: It shaped the characteristic Dutch art of the Golden Age. The research focuses on the sub-genre of the vanitas still life, particularly the type which includes as part of its composition a human face, a physiognomic likeness by way of a print, painted portrait, painted tronie, or a sculpture. This thesis attempts to utilize this artistic tradition as a vehicle to delve into the aspects of realism and iconography in Dutch seventeenth-century art. To provide context the introduction deals with the Dutch Republic and the conditions that made this art feasible. A brief historiography of still life and vanitas still life follows. The research then delves into the still life paintings with a portrait, print or sculpture, with examples from twelve artists, and attempts to understand the relationships that exist between the objects rendered. The trends within this subject matter revolve around a master artist, other times around a city such as Haarlem, Leiden or country, England. The research looks closely at specific paintings of different artists, with a thematic focus of artist portraits, historical figures, painted tronies, and sculpture within the vanitas still life sub-genre. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2017 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Photodeath As Memento Mori- a Contemporary

Photodeath as Memento Mori- A Contemporary Investigation by Catherine Dowdier, B.A., B. Vis Arts, Grad. Dip. Faculty of Fine Arts, Northern Territory University Master of Arts by Research 18. 09. 1996 ThesisDeclaration: I herebydeclare that thework herein,now submitted as a thesis for the degree of Master by Research, is theresult of my own investigations, and all references to ideas and work of otherresearchers have been specifically acknowledged. I herby certify that the work embodied in this thesis has not already beenaccepted in substance for any degree, and is not beingcurr ently submittedin candidature for any other degree. 1i4 U/�� .l... .................................................... Catherine Bowdler Table of Contents Introduction . 1 Chapter 1: Memento Mori . 5 Chapter 2: Photodeath . 15 Chapter 3: ChristianBoltanski . 26 Chapter 4: Joel Peter Witkin . 48 Chapter 5: Peter Hujar . 64 Conclusion........... ..............................................7 4 Bibliography . 80 lliustrations . 84 List of Illustrations 1. "LesArchives", Christian Boltanski, 1989 2. "Reserves:La Fete de Purim", 1989 3. "Still LifeMarseilles", Joel Peter Witkin, 1992 4. "Le Baiser", Joel Peter Witkin, 1982 5. ''Susan Sontag", Peter Hujar, 1976 6. "Devine", PeterHujar, 1976 Abstract This thesis is an exploration of the links between the notions exemplified in traditional memento mori imagery and the Barthian concept of 'photodeath'. In order to do this I have chosen three contemporary photographers: Christian Boltanski, Joel Peter Witkin andPeter Hujar, in whosework bothconcepts are manifest in completely different ways. Theconcepts of mementomori and photodeath are initially discussed separately in some detail. Then, by careful examinationof key works in each artist'soeuvre, some critical observations aboutthe nature of both concepts are teased out and explored.