Art As a Catalyst to Activate Public Space: the Experience of 'Triumphs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts and Culture Unnumbered Sparks: Janet Echelman, TED Sculpture Foreword

Arts and Culture Unnumbered Sparks: Janet Echelman, TED Sculpture Foreword Imagine a world without performing or visual arts. Imagine – no opera houses, no theatres or concert halls, no galleries or museums, no dance, music, theatre, collaborative arts or circus – and in an instant we appreciate the essential, colourful, emotive and inspiring place that creative pursuits hold in our daily life. Creating opportunities for arts to flourish is vital, and this includes realising inspiring venues which are cutting edge, beautiful, functional, sustainable, have the right balance of architecture, acoustics, theatrical and visual functionality and most importantly are magnets for artists and audiences, are enjoyable spaces and places, and allow the shows and exhibitions to go on. 4 Performing Arts Bendigo Art Gallery 5 Performing Arts Arts and Culture Performing and Visual Arts 03 08 – 87 88 – 105 Foreword Performing Musicians, Arts Artists, Sculptors and Festivals 106 – 139 140 – 143 144 Visual Arup Services Photography Arts Clients and Credits Collaborators Contents Foreword 3 Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall 46 Singapore South Bank Studio, Queensland Symphony Orchestra 50 Australia Performing Marina Bay Sands Theatres 52 Arts 8 Singapore Elisabeth Murdoch Hall Federation Concert Hall 56 Melbourne Recital Centre 10 Australia Australia Chatswood Civic Place 58 Sydney Opera House 14 Australia Australia Carriageworks 60 Glasshouse Arts, Conference and Australia Entertainment Centre 16 Australia Greening the Arts Portfolio 64 Australia Melbourne -

Flying Over the Abyss Η Υπερβαση Τησ Αβυσσοσ

FLYING OVER THE ABYSS Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΒΥΣΣΟΣ 7 NOVEMBER 2015 – 29 FEBRUARY 2016 CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI - STATE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART FLYING OVER THE ABYSS Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΒΥΣΣΟΣ CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI Tuesday - Wednesday - Thursday - Saturday - Sunday 10:00-18:00 Friday 10:00-22:00 Monday Closed All works exhibited are courtesy of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection. Our warmest thanks to the D.Daskalopoulos Collection and Nikos Kazantzakis Museum for their generous loans to the exhibition. Marina Abramović Alexis Akrithakis Matthew Barney Hans Bellmer Lynda Benglis John Bock Louise Bourgeois Heidi Bucher Helen Chadwick Savvas Christodoulides Abraham Cruzvillegas Robert Gober Asta Gröting Jim Hodges Jenny Holzer Kostas Ioannidis Mike Kelley William Kentridge Martin Kippenberger Sophia Kosmaoglou Sherrie Levine Stathis Logothetis Ana Mendieta Maro Michalakakos Doris Salcedo Kiki Smith Costas Tsoclis Mark Wallinger CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE OF THESSALONIKI Suggested exhibition route according to room numbering Ground floor 1st floor ROOM 2 ROOM 1 ROOM 2 ROOM 3 ROOM 4 ROOM 5 ROOM 2 Tracing a human being’s natural course from life to death, the exhibition Flying over the Abyss follows, in a way, the flow of the universal text of The Saviors of God by that great Cretan, Nikos FLYING OVER Kazantzakis. It neither illustrates, nor narrates. The text, concretely actual and precious, in its original manuscript, does remain complete in its roundness and maximum in its creative artistry. THE ABYSS Unravelled comes along the harrowing of the other, not alienated, yet refreshing moments of the Η ΥΠΕΡΒΑΣΗ contemporary artistic creation. In the exhibition, works by Greek and international artists share in, pointing out the trauma of birth, the luminous interval of life and creativity, and death. -

PDF Press Release

P R E S S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 4, 2008 Williams College Museum of Art Presents William Kentridge Prints February 9 – April 27, 2008 and June 21 – August 24, 2008 and History of the Main Complaint, 1996 February 2–April 27, 2008 Williamstown, MA—The Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) presents William Kentridge Prints, the first of a two-part exhibition, which features 120 works by this pioneering South-African artist. WCMA will also be showing Kentridge's film History of the Main Complaint, 1996, in the museum's media field gallery. Okwui Enwezor, Dean of Academic Affairs at San Francisco Art Institute and Adjunct Curator at International Center of Photography, New York, will give a lecture entitled "(Un) Civil Engineering: William Kentridge's Allegorical Landscapes" on Saturday, April 12 at 2:00 pm in Brooks -Rogers Recital Hall at Williams College. This is a free public program and all are invited to attend. William Kentridge Prints represents over a third of the out put in the medium of printmaking for Kentridge, who works in the tradition of socially and politically engaged artists such as William Hogarth, Francisco Goya, Honore Daumier, and Kathe Kollwitz. Kentridge's work reflects on the human condition, specifically the history of apartheid in his own country and the ways in which our personal and collective histories are intertwined. The work in this exhibition ranges from 1976 to 2004 and includes aquatint, drypoint, engraving, etching, monoprint, 15 LAWRENCE HALL DRIVE SUITE 2 WILLIAMSTOWN MASSACHUSETTS 01267-2566 telephone 413.597.2429 facsimile 413.458.9017 web WWW.WCMA.ORG linocut, lithograph, and silkscreen techniques, often in combinations. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

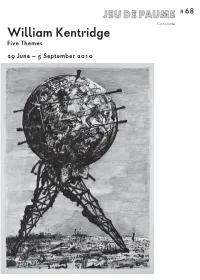

William Kentridge Five Themes 29 June – 5 September 2010 Invisible Mending, from the Installation 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003

# 68 Concorde William Kentridge Five Themes 29 June – 5 September 2010 Invisible Mending, from the installation 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003 South African artist William Kentridge (born between them, shifting from theatre to drawing 1955) first achieved international recognition or from drawing to film. Though his work in the 1990s with a series of what he called resonates with the South African experience, “drawings for projection”: short animated films Kentridge also draws on varied European based on everyday life under apartheid. Since sources, including literature, opera, theatre and then, Kentridge has widened his thematic range, early cinema, to create a complex universe expanding beyond his immediate environment where good and evil are complementary and to examine other political conflicts. His oeuvre inseparable forces. charts a universal history of war and revolution, An important conceptual development in evoking the complexities and tensions of Kentridge’s practice of recent years is the artist’s postcolonial memory and imaging the residual self-reflexive yet playful focus on his relationship traces of devastating policies and regimes. to the world. Whereas the early charcoal The first retrospective in France devoted to the animations operated with a cast of fictional artist is centred on the broad themes that have characters, Kentridge himself now appears as motivated Kentridge during his career, through the principal character in his own creations. By a large choice of works dating from the late referencing optical illusion and the mechanics 1980s to today. While putting the accent on of perception, in his latest works, Kentridge recent pieces, it highlights the broad scope moves beyond the characteristic manipulations of Kentridge’s artistic practice and diversity of animation to create a world conceived as a of media, including drawing, film, collage, theatre of memory. -

24-25 June 2016 Conveners: Emma Dillon, Ziad Elmarsafy, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes

1 The Musical Pasts Consortium I Music and the Urban King’s College London: 24-25 June 2016 Conveners: Emma Dillon, Ziad Elmarsafy, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes FRIDAY 24 JUNE (THE ANATOMY MUSEUM, KING’S COLLEGE LONDON, STRAND CAMPUS) SESSION 1 (9:30-12:30) Introductory (Chair: James Chandler) Discussion of pre-circulated reading (Emma Dillon, Roger Parker, Martin Stokes): David Harvey Rebel Cities (Verso, 2013), pp. 115-53 Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World (Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 241-49 and pp. 283-321 David Wallace, Europe: A Literary History, 1348-1418 (Oxford University Press), vol. 1, pp. xxvii-xlii Coffee (10:45-11:15) Discussion 1 (Chair: Gary Tomlinson) Martha Feldman: A sound recording (remastered) of the castrato Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922) singing Paolo Tosti’s song “Ideale” for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company Ltd, recorded in Rome in April 1902. (see attachment) Katherine Schofield: “Shruti-vina”, sent from Calcutta by Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore to be exhibited at the 1886 Colonial and India Exhibition in London, and thence donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1890. (see attachment) Michael Denning: A son pregón, “El Manisero,” recorded by the Havana son trio, Trio Matamoros, in New York in July 1929 (Victor 46401, released in Accra and Lagos in 1933 as HMV GV 3), “that deplorable rhumba” (Jorge Luis Borges), a stylization of an urban street vendor’s cry (the peanut vendor). Source: The Legendary Trio Matamoros, Tumbao TCD-016, 1992. (see attachment) Lunch (12:30-2:00) 2 SESSION 2 (2:00-5:30) Discussion 2 (Chair: Flora Willson) Mary Ann Smart: A passage taken from the book Viaggio a Londra, part of a six- volume series of travel guides published in Bologna in 1837. -

William Kentridge Thick Time 21 September - 15 January 2017 Large Print Labels and Interpretation Gallery 1

William Kentridge Thick Time 21 September - 15 January 2017 Large print labels and interpretation Gallery 1 1 Left of gallery door: William Kentridge Thick Time William Kentridge (b.1955) lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa. This exhibition takes a journey through a series of environments he created between 2003 and 2016. His work spans drawing and printmaking, film, performance, dance, music, tapestry and sculpture. Kentridge’s expressionist drawings stand in a tradition of radical figuration from Francisco de Goya in the 19th century to Max Beckmann, George Grosz or Käthe Kollwitz in the early 20th century. His great skill as a draughtsman combines with his interest in early cinema and in theatre. (continues on next page) 2 The experience of studying radical mime and acting techniques at L’École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris and being part of an experimental theatre group in Johannesburg in the late 1970s and 1980s has been a major influence. Kentridge often collaborates with composers, dancers, musicians, puppeteers and designers; and has directed a number of operas. Six immersive installations are located over two floors of the museum. The themes in Kentridge’s work emerge from his experience of apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa and his reflections on colonialism and exile. The works also show his fascination with the utopian aspirations of early Modernism; the science and politics of time and space; the beauty and fragility of the natural world; and the nature of creativity. 3 Right side of gallery door: Untitled (Bicycle Wheel II) n/a 2012 Steel, timber, brass, aluminium, bicycle parts and found objects Courtesy William Kentridge; Marian Goodman Gallery (New York/Paris/London); Goodman Gallery (Johannesburga and Cape Town); Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan) 4 Left of gallery, clockwise: WILLIAM KENTRIDGE: THICK TIME This gallery presents three installations. -

Kentridge's Nose*

Kentridge’s Nose* MARIA GOUGH Gogol’s grotesque raged around us; what were we to understand as farce, what as prophecy? The incredible orchestral combinations, texts seemingly unthinkable to sing . t he unhabitual rhythms . t he incorporat - ing of the apparently anti-poetic, anti-musical, vulgar, but what was in reality the intonation and parody of real life—all this was an assault on conventionality. —Grigorii Kozintsev (1969), on the 1930 Leningrad premiere of The Nose If one holds onto the discoveries, the risks and inven - tions of the Russian avant-garde . one also has to find a place not simply to acknowledge, but to house the faith animating the work of its members—their belief in a transformed society. —William Kentridge (2008) In his quest for an all-out renewal of operatic form, Peter Gelb, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera in New York since 2006, packed the 2009 –2010 season with eight new productions, essentially bringing to a close the reign of Franco Zeffirelli, whose florid, love-it or hate-it Neapolitanesque scenography has more or less dominated the proscenium for decades, at least with respect to the Italian reper - toire. With just one exception, all the new additions to the Met’s inventory this past * Sincere thanks to Tom Cummins for generously enabling my graduate seminar to attend the premiere of The Nose at the Met, to Jodi Hauptman for arranging entry to the performance of William Kentridge’s theatrical monologue I Am Not Me, The Horse Is Not Mine at the Museum of Modern Art, to Leah Dickerman and the October editors for inviting the present reflection, and to Eve-Laure Moros Ortega, Ian Forster, Art 21 Inc., Marian Goodman Gallery, Sam Johnson, Hugh Truslow, and Adam Lehner for various forms of invaluable assistance. -

M O MA Highligh Ts M O MA Highligh Ts

MoMA Highlights MoMA Highlights MoMA This revised and redesigned edition of MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art presents a new selection from the Museum’s unparalleled collection of modern and contemporary art. Each work receives a vibrant image and an informative text, and 115 works make their first appearance in Highlights, many of them recent acquisitions reflecting the Museum’s commitment to the art of our time. 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art New York MoMA Highlights 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2 3 Introduction Generous support for this publication is Produced by the Department of Publications What is The Museum of Modern Art? 53rd Street, from a single curatorial The Museum of Modern Art, New York provided by the Research and Scholarly At first glance, this seems like a rela- department to seven (including the Publications Program of The Museum of Edited by Harriet Schoenholz Bee, Cassandra Heliczer, tively straightforward question. But the most recently established one, Media Modern Art, which was initiated with the sup- and Sarah McFadden Designed by Katy Homans answer is neither simple nor straight- and Performance Art, founded in port of a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Production by Matthew Pimm forward, and any attempt to answer it 2006), and from a program without a Foundation. Publication is made possible Color separations by Evergreen Colour Separation permanent collection to a collection of by an endowment fund established by The (International) Co., Ltd., Hong Kong almost immediately reveals a complex Printed in China by OGI/1010 Printing International Ltd. -

10 Ways of Thinking Through Drawing

Interpretive Resource 10 Ways of Thinking Through Drawing Written by Kylie Neagle, Education Officer and Thomas Readett, Tarnanthi Education Officer 1 10 Ways of Thinking Through Drawing Who is William Kentridge? Artist William Kentridge was born in 1955 in South Africa and currently lives and works in Johannesburg. His arts practice is diverse and includes drawing, painting, collage, printmaking, sculpture, tapestry, theatre and photography. Kentridge is best known for his animated charcoal drawings, where he erases and alters his images, photographing or filming the work in between each modification. The photographs and film are then combined to create a stop-motion animation. History and memory, its excavation and erasure, lies at the heart of Kentridge’s practice. Through a transformation of materials, he explores themes of colonisation and reference his experiences of the apartheid regime in South Africa, which was a system of racial segregation that existed from 1948 to the early 1990s. Spanning Kentridge’s thirty-year career, the works in this exhibition draw connections between the myriad aspects of his William Kentridge, South Africa, born 1955, The Hope in the Charcoal Cloud, 2014, Johannesburg, charcoal, coloured pencil, Indian ink, digital print, and watercolour on pages of Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 160.0 x 120.0 cm; practice, infused with narratives, the absurd, terror and drama. Collection of Naomi Milgrom AO, © William Kentridge, photo: Christian Capurro. 2 Resources Books Articles Taylor. J, Kentridge: that which we do not remember, Golby, M. ‘The Conversation’, William Kentridge: the Supported by the Naomi Milgrom Foundation, 2019 barbarity of the ‘Great War’ told through an Kentridge W. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 500 Nations DVD-0778 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 500 Years Later DVD-5438 180 DVD-3999 56 Up DVD-8322 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 60's DVD-0410 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 7 Years DVD-4399 1964 DVD-7724 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 70's Dimension DVD-1568 1993 World Trade Center Bombing DVD-1891 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 900 Women DVD-2068 DVD-4941 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 21 Up DVD-1061 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Abolitionists DVD-7362 24 City DVD-9072 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 28 Up DVD-1066 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 35 Up DVD-1072 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Act of Killing DVD-4434 42 Up DVD-1079 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 -

Ouauq PRIVATE IUMATAMUT TUMATAITI

ouauq PRIVATE IUMATAMUT TUMATAITI The 2nd Auckland Triennial AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND 2004 MARK ADAMS (NZ) / LAURIE ANDERSON (USA) / TIONG ANG (NETHERLANDS) / JOHN! BARBOUR (AUSTRALIA) / POLLY BORLAND! ||( UK / AUSTRALIA) / LOUISA BUFARDECI (AUSTRALIA) / MUTLU £ERKEZ (AUSTRALIA) /[ CHRIS CUNNINGHAM (UK) / MARGARET DAWSON! || (N Z) / ET AL. (NZ) / KATHLEEN HERBERT ||( UK) / JENNY HOLZER (USA) / LONNIE! jjHUTCHINSON (NZ) / ILYA & EMILIA KABAKOV! I(USSR/USA) / KAO CHUNG-LI (TAIWAN) / EMIKO ! KASAHARA (JAPAN) / WILLIAM KENTRIDGE: (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) / JAKOB! IIk OLDING (DENMARK) / LAUREN LYSAGHT (NZ) /] EMILY MAFILE'0 (NZ) / THANDO MAMA ||( REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) / SEN ZEN I MARASELA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) /| TERESA MARGOLLES (MEXICO) / ANDREW IlMCLEOD (NZ) / JULIA MORISON (NZ) / CALLUM! MORTON (AUSTRALIA) / FIONA PARDINGTON! ||( NZ) / NEIL PARDINGTON (NZ) / ROBERT! •PULI E (AUSTRALIA) / LISA REIHANA (NZ) /j CATHERINE ROGERS (AUSTRALIA) / SANGEETA SANDRASEGAR (AUSTRALIA) / AVA SEYMOUR^ (NZ) / LORNA SIMPSON (USA) / SEAN SNYDER: [[(GERMANY / USA) / KATHY TEMIN (AUSTRALIA) /| HULLEAH J . TSINHNAHJ INNIE (USA) / J ANEi lift LOUISE WILSON (UK) / YUAN GOANG-MINGj : (TAIWAN) PUBLIC 3 T A v m q TUMATANUI ITIATAMUT EXHIBITION CURATORS: NGAHIRAKA MASON EWEN MCDONALD i The 2nd Auckland Triennial AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND 20 MARCH - 30 MAY 2004 THE AUCKLAND ART GA L L E R Y_T H E UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND'S GUS FISHER GALLERY_GE0RGE FRASER GALLERY_ARTSPACE JENNY GIBBS GRAEME EDWARDS SUE FISHER give HARRIET FRIEDLANDER ART T R U S T ISimpson Grierson