The Resilience of Diana's Cult at Lake Nemi in Contrast To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

NOTES on the CYNEGETICA of Ps. OPPIAN

NOTES ON THE CYNEGETICA OF Ps. OPPIAN. En este artículo tratamos quince pasajes de las "Cinegéticas" que se atribuyen a Oppiano, los cuales comentamos de modo crítico e interpretativo. Llevamos a cabo el intento, antes de ser aceptada cualquier modificación de la tradición manuscrita, de realizar un estudio del texto, dentro del marco de la técnica ale- jandrina, y de las particularidades que presenta la lengua de esta época. Los pasajes que tratamos son los siguientes: C. 11 8, 260, 589, 111 22, 37, 183, 199, 360, IV 64, 177, 248, 277, 357, 407, 446. Boudreaux's edition of ps.- Oppian's Cynegetica, Paris 1908, an impressive work of profound and acute scholarship, has basically esta- blished the text of the poem and almost a century after its publication is the standard work for those who study ps.- Oppian. However, I think there is still room for improvement in the text. In this paper I would like to discuss various passages from the Cynegetica in the hope of cla- rifying them. For the convenience of the reader I print Boudreaux's text followed by Mair's translation. In the proemium of the second book the poet of the Cynegetica refers to the first hunters; according to the poet, Perseus was first among men to hunt, line 8ff.: ' Ev ilEp(517EGat 6 -rrpo5Tos- ô fopyóvos ctiiVva kóIpag ZrivOg xpuo-Eioto TrCíÏç KXUTÓS, EWETO nEpaeúg- áxxa Tro865v twatuvijo-tv ŬELOp_EVOS ITTEplj'yEaal KOli ITTC5Kag Kal 06.1ag EXaCUTO Kal yb)09 aly6JV 104 NOTES ON THE CYNEGETICA OF Ps. OPPIAN ĉrypoTépow8ópkoug TE 0001/9 Opirywv TE -yv€0Xct ctin-t5v éXd(1)WV 071.1(T(5V ClITTTO KápTiVa. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

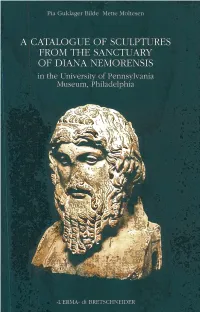

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

Pantheon Piazza Della Rotonda, 00186 Near Piazza Novanametro: 9 AM – 7:30 PM (Mon – Sat)

Pantheon Piazza della Rotonda, 00186 Near Piazza NovanaMetro: 9 AM – 7:30 PM (Mon – Sat) 9 AM – 6 PM (Sunday) The Roman Pantheon is the most preserved and influential building of ancient Rome. It is a Roman temple dedicated to all the gods of pagan Rome. As the brick stamps on the side of the building reveal it was built and dedicated between A.D 118 and 125. The emperor Hadrian (A.D 117-138) built the Pantheon to replace Augustus’ friend and Commander Marcus Agrippa’s Pantheon of 27 B.C. which burnt to the ground in 80 A.D. When approaching the front of the Pantheon one can see the inscription above still reads in Latin the original dedication by Marcus Agrippa. The inscription reads: "M. AGRIPPA.L.F.COSTERTIUM.FECIT” “Marcus Agrippa son of Lucius, having been consul three times made it”. Despite all the marvelous building projects that the emperor Hadrian produced during his reign, he never inscribed his name to any, but one, the temple of his father Trajan. That is why the Roman Pantheon bears the inscription of Marcus Agrippa, and not the emperor Hadrian. The pediment (the triangle section above the inscription) is blank today, but there would have been sculpture that acted out the battle of the Titans. Great bronze doors guard the entrance to the cella and would have been covered in gold, but it has long since disappeared. The original use of the Pantheon is somewhat unknown, except that is was classified as a temple. However, it is unknown as to how the people worshipped in the building, because the structure of the temple is so different from other traditional Roman temples such as in the Roman Forum. -

Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions About the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: the Influence of Religion

NOTA DI LAVORO 08.2010 Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions about the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: The Influence of Religion By Paul Sarfo-Mensah, Bureau of Integrated Rural Development, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana William Oduro, Wildlife and Range Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, CANR, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana GLOBAL CHALLENGES Series Editor: Gianmarco I.P. Ottaviano Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions about the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: The Influence of Religion By Paul Sarfo-Mensah, Bureau of Integrated Rural Development, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana William Oduro, Wildlife and Range Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, CANR, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana Summary The potential of traditional natural resources management for biodiversity conservation and the improvement of sustainable rural livelihoods is no longer in doubt. In sub-Saharan Africa, extensive habitat destruction, degradation, and severe depletion of wildlife, which have seriously reduced biodiversity and undermined the livelihoods of many people in rural communities, have been attributed mainly to the erosion of traditional strategies for natural resources management. In Ghana, recent studies point to an increasing disregard for traditional rules and regulations, beliefs and practices that are associated with natural resources management. Traditional natural resources management in many typically indigenous communities in Ghana derives from changes in the perceptions and attitudes of local people towards tumi, the traditional belief in super natural power suffused in nature by Onyame, the Supreme Creator Deity. -

Diana (Old Lady) Apollo (Old Man) Mars (Old Man)

Diana (old lady) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. Ap. (yawning.) I shan't go out today. I was out yesterday and the day before and I want a little rest. I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel my work a great deal more than I used to. Dia. I'm sure these short days can't hurt you. Why, you don't rise till six and you're in bed again by five: you should have a turn at my work and just see how you like that - out all night! Apollo (Old man) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. -

Geochemicaljournal,Vol.28,Pp. 173To 184,1994 C H

GeochemicalJournal,Vol.28,pp. 173to 184,1994 C h em ic al c h a r acters of cr ater la k es in th e A z o res a n d Italy: th e a n o m aly o f L a k e A lb a n o M ARlNO M ARTlNl,1 L UCIANO GIANNINl,1 FRANCO PRATI,1 FRANCO TASSI,l B RUNO CAPACCIONl2 and PAOLO IOZZELL13 IDepartm ent ofEarth Sciences,U niversity ofFlorence, 50121 Florence,Italy 2lnstitute ofV olcanology and G eochemistry, University ofUrbino, 61029 Urbino,Italy 3Departm ent ofPharm aceutical Sciences, University ofFlorence,50121 Florence,Italy (Received April23, 1993,・Accepted January 10, 1994) Investigations have been carried out on craterlakesin areas ofrecent volcanism in the A zores and in Italy, with the aim of detecting possible evidence of residual anom alies associated with past volcanic activities;data from craterlakes ofCam eroon have been considered for com parison. A m ong the physical- chem ical ch aracters taken into account, the increases of tem perature, am m onium and dissolved carbon dioxide with depth are interp reted as providing inform ation aboutthe contribution of endogene fluidsto the lake w ater budgets. The greater extent of such evidence at Lakes M onoun and N yos (Cam eroon) appears associated withthe disastersthatoccurred there duringthe lastdecade;som e sim ilarities observed atLake Albano (Italy)suggesta potentialinstability also forthis craterlake. parison. W ith reference to the data collected so INTRODUCT ION far and considering the possibility that the actual Crater lakes in active volcanic system s have chem ical characters ofcrater lakes are influenced been investigated with reference to change s oc- by residualtherm al anom alies in the hosting vol- curing in w ater chem istry in response to different canic system s, an effort has been m ade to verify stages of activity, and interesting inform ation is w hether and to w hat extent these anom alies can available about R u apehu (Giggenbach, 1974), be revealed by sim ple observations. -

And Rome's Legacies

Christianity AND ROME’S LEGACIES Old Religions New Testament MARK MAKES HIS MARK NOT SO SIMPLE TEMPLES IN PARTNERSHIP WITH christianity_FC.indd 1 3/6/17 3:32 PM 2 Religions in Rome The earliest Romans saw their gods as spirits or powerful forces of nature. These gods did not have personalities or emotions or act in any other way like human beings. However, as Rome began to build an empire, the Romans were exposed to new ideas. Through contact with the Greeks, the Romans’ idea of gods and goddesses changed. The Greeks believed in gods and god- desses who behaved very much like human beings. Their gods could be jeal- ous, angry, passionate, kind, foolish, or petty. The Romans borrowed this idea u THE ROMANS People did not go to and honey, burned honored their gods a temple to worship sweet-smelling from the Greeks. They even borrowed by building temples. the god. Rather, a incense, and sac- some of the Greek gods and goddesses. Inside each temple temple was where rificed animals to No longer were the Roman gods spir- was a statue of a priests made honor the god. god or goddess. offerings of cakes its or forces of nature. They were now divine and human at the same time. u UNTIL THE in private people 300s CE, the Roman were free to think u THE ROMANS wisdom. During festival day, priests ticular, no legal religion was a and say what they honored their gods Cerealia, Romans performed rituals work was allowed. state religion. wanted to. Over with more than 100 honored the god- and sacrifices Celebrations includ- The emperor was time, the emperor festivals every year. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

Forward and Backward Private Searchable Encryption from Constrained Cryptographic Primitives

Forward and Backward Private Searchable Encryption from Constrained Cryptographic Primitives Raphael Bost∗ Brice Minaudy Olga Ohrimenkoz Abstract Using dynamic Searchable Symmetric Encryption, a user with limited storage resources can securely outsource a database to an untrusted server, in such a way that the database can still be searched and updated efficiently. For these schemes, it would be desirable that updates do not reveal any information a priori about the modifications they carry out, and that deleted results remain inaccessible to the server a posteriori. If the first property, called forward privacy, has been the main motivation of recent works, the second one, backward privacy, has been overlooked. In this paper, we study for the first time the notion of backward privacy for searchable encryption. After giving formal definitions for different flavors of backward privacy, we present several schemes achieving both forward and backward privacy, with various efficiency trade-offs. Our constructions crucially rely on primitives such as constrained pseudo-random functions and punc- turable encryption schemes. Using these advanced cryptographic primitives allows for a fine-grained control of the power of the adversary, preventing her from evaluating functions on selected inputs, or de- crypting specific ciphertexts. In turn, this high degree of control allows our SSE constructions to achieve the stronger forms of privacy outlined above. As an example, we present a framework to construct forward-private schemes from range-constrained pseudo-random functions. Finally, we provide experimental results for implementations of our schemes, and study their practical efficiency. 1 Introduction Symmetric Searchable Encryption (SSE) enables a client to outsource the storage of private data to an untrusted server, while retaining the ability to issue search queries over the outsourced data. -

THE MARS ULTOR COINS of C. 19-16 BC

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 9/2015 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką s . 7-30 Victoria Győri King’s College, London THE MARS ULTOR COINS OF C. 19-16 BC In 42 BC Augustus vowed to build a temple of Mars if he were victorious in aveng- ing the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar1 . While ultio on Brutus and Cassius was a well-grounded theme in Roman society at large and was the principal slogan of Augustus and the Caesarians before and after the Battle of Philippi, the vow remained unfulfilled until 20 BC2 . In 20 BC, Augustus renewed his vow to Mars Ultor when Roman standards lost to the Parthians in 53, 40, and 36 BC were recovered by diplomatic negotiations . The temple of Mars Ultor then took on a new role; it hon- oured Rome’s ultio exacted from the Parthians . Parthia had been depicted as a prime foe ever since Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC . Before his death in 44 BC, Caesar planned a Parthian campaign3 . In 40 BC L . Decidius Saxa was defeated when Parthian forces invaded Roman Syria . In 36 BC Antony’s Parthian campaign was in the end unsuccessful4 . Indeed, the Forum Temple of Mars Ultor was not dedicated until 2 BC when Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae and when Gaius departed to the East to turn the diplomatic settlement of 20 BC into a military victory . Nevertheless, Augustus made his Parthian success of 20 BC the centre of a grand “propagandistic” programme, the principal theme of his new forum, and the reason for renewing his vow to build a temple to Mars Ultor . -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890.