The Non-Constituents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Report HRC Bosnia

Written Information for the Consideration of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Second Periodic Report by the Human Rights Committee (CCPR/C/BIH/2) SEPTEMBER 2012 Submitted by TRIAL (Swiss Association against Impunity) Association of the Concentration Camp-Detainees Bosnia and Herzegovina Association of Detained – Association of Camp-Detainees of Brčko District Bosnia and Herzegovina Association of Families of Killed and Missing Defenders of the Homeland War from Bugojno Municipality Association of Relatives of Missing Persons from Ilijaš Municipality Association of Relatives of Missing Persons from Kalinovik (“Istina-Kalinovik ‘92”) Association of Relatives of Missing Persons of the Sarajevo-Romanija Region Association of Relatives of Missing Persons of the Vogošća Municipality Association Women from Prijedor – Izvor Association of Women-Victims of War Croatian Association of War Prisoners of the Homeland War in Canton of Central Bosnia Croatian Association of Camp-Detainees from the Homeland War in Vareš Prijedor 92 Regional Association of Concentration Camp-Detainees Višegrad Sumejja Gerc Union of Concentration Camp-Detainees of Sarajevo-Romanija Region Vive Žene Tuzla Women’s Section of the Association of Concentration Camp Torture Survivors Canton Sarajevo TRIAL P.O. Box 5116 CH-1211 Geneva 11 Tél/Fax: +41 22 3216110 [email protected] www.trial-ch.org CCP: 17-162954-3 CONTENTS Contents Paragraphs Background 1. Right to Life and Prohibition of Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, Remedies and Administration of Justice (Arts. 6, -

Tuzla Is a City in the Northeastern Part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It Is the Seat of the Tuzla Canton and Is the Econo

Summary: Tuzla is a city in the northeastern part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the seat of the Tuzla Canton and is the economic, scientific, cultural, educational, health and tourist centre of northeast Bosnia. Preliminary results from the 2013 Census indicate that the municipality has a population of 120,441. District Heating System of Tuzla City started in October 1983. Project to supply Tuzla City with heat energy from Tuzla Power Plant that will have combined production of electricity and heat was happened in 4 phases. The requirements for connection to Tuzla District Heating brought of system in position that in 2005 we got to the maximum capacity and we had to do wide modernization of network pipes and heat substations. Facts about the Tuzla district energy system Annual heat carrying capacity: 300,000 MWth Temperature: 130–60°C Transmission network length: 19.6 km (2x9.8 km) Distribution network length: 142.4 km (2x71.2 km) Power station fuel: Coal Number of users: Total: 22934 Flats snd Houses: 20979 Public Institutions: 156 Commercial units: 1799 Heated area (square meters): Total: 1718787 Flats and Houses: 1158402 Public Institutions: 220460 Commercial units: 339925 Results achieved by reengineering the Tuzla district energy system • 30 % energy savings compared to old system before retrofit • Capacity expanded by 36 % within the existing flow of 2,300 m3/h • Reengineering of 98 substations: ball valves, strainers, pressure regulators, control valves, temperature and pressure sensors, safety thermostats, weather stations, electronic controllers, thermostatic radiator valves (TRVs), energy meters Tuzla is a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the seat of the Tuzla Canton and is the economic, scientific, cultural, educational, health and tourist centre of northeast Bosnia. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Joint Opinion on the Legal

Strasbourg, Warsaw, 9 December 2019 CDL-AD(2019)026 Opinion No. 951/2019 Or. Engl. ODIHR Opinion Nr.:FoA-BiH/360/2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS (OSCE/ODIHR) BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JOINT OPINION ON THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING THE FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, IN ITS TWO ENTITIES AND IN BRČKO DISTRICT Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 121st Plenary Session (Venice, 6-7 December 2019) On the basis of comments by Ms Claire BAZY-MALAURIE (Member, France) Mr Paolo CAROZZA (Member, United States of America) Mr Nicolae ESANU (Substitute member, Moldova) Mr Jean-Claude SCHOLSEM (substitute member, Belgium) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2019)026 - 2 - Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 II. Background and Scope of the Opinion ...................................................................... 4 III. International Standards .............................................................................................. 5 IV. Legal context and legislative competence .................................................................. 6 V. Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 8 A. Definitions of public assembly .................................................................................. -

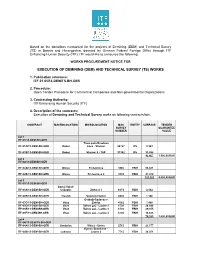

Execution of Demining (Dem) and Technical Survey (Ts) Works

Based on the donations earmarked for the projects of Demining (DEM) and Technical Survey (TS) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, donated by German Federal Foreign Office through ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF), ITF would like to announce the following: WORKS PROCUREMENT NOTICE FOR EXECUTION OF DEMINING (DEM) AND TECHNICAL SURVEY (TS) WORKS 1. Publication reference: ITF-01-05/13-DEM/TS-BH-GER 2. Procedure: Open Tender Procedure for Commercial Companies and Non-governmental Organizations 3. Contracting Authority: ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF) 4. Description of the contracts: Execution of Demining and Technical Survey works on following contracts/lots: CONTRACT MACROLOCATION MICROLOCATION MAC ENTITY SURFACE TENDER SURVEY GUARANTEE NUMBER VALUE Lot 1 ITF-01/13-DEM-BH-GER Trasa puta Hrastova ITF-01A/13-DEM-BH-GER Doboj kosa - Stanovi 50767 RS 9.369 ITF-01B/13-DEM-BH-GER Doboj Stanovi 9 - TAP 51392 RS 33.098 42.467 1.500,00 EUR Lot 2 ITF-02/13-DEM-BH-GER ITF-02A/13-DEM-BH-GER Olovo Pridvornica 9386 FBiH 53.831 ITF-02B/13-DEM-BH-GER Olovo Pridvornica 5 9393 FBiH 47.470 101.301 4.000,00 EUR Lot 3 ITF-03/13-DEM-BH-GER Gornji Vakuf- ITF-03A/13-DEM-BH-GER Uskoplje Zdrimci 1 6673 FBiH 2.542 ITF-03B/13-DEM-BH-GER Travnik Vodovod Seferi 8538 FBiH 1.186 Grabalji-Sadavace- ITF-03C/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Zabilje 4582 FBiH 7.408 ITF-03D/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 2 6702 FBiH 28.846 ITF-03E/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 3 6703 FBiH 20.355 ITF-03F/13-DEM-BH-GER Vitez Šehov gaj – Lazine 4 6704 FBiH 18.826 79.163 3.000,00 EUR Lot 4 ITF-04/13-DEM/TS-BH-GER -

Co-Processing of Municipal Waste…

Co -processing of municipal waste as an alternative fuel in the cement industry in BiH Bulletin of the project – November 2017 ABOUT THE PROJECT The project "Co-processing of municipal municipalities, public utility companies alternative fuels, in accordance with the waste as an alternative fuel in the cement and private companies from the Zenica- legislation of BiH and the European Union. industry in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH)" Doboj, Central Bosnia Canton and Sarajevo is a very successful example of cooperation Canton participated in the events since Sanela Veljkovski between the private and public sectors in they are to inform on the objectives and Project Coordinator, GIZ - Programm developpp.de the area of environmental protection and obligations related to the waste research on the possibilities of improving management system on the federal level. the waste management system. Bearing in mind the negative impact of The project is funded by the German uncontrolled waste disposal on the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation environment, this project proposes and Development and implemented by the solutions for reducing the amount of waste German Organization for International deposited in landfills. Namely, through a Content Cooperation GIZ - Program develoPPP.de large number of studies and analyzes, and the Cement Factory Kakanj (TCK), opportunities have been explored in which along with their partner organizations - municipalities could be suppliers of cement Page 1 - About the project, Sanela Veljkovski the Regional Development Agency for plants in the future with alternative fuel Page 2 - Promotional activities Part 1 Central BiH Region (REZ Agency) and the (fuel from waste). Page 3 - Promotional activities Part 2 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the The process of converting waste into University of Zenica. -

European Social Charter the Government of Bosnia And

16/06/2021 RAP/RCha/BIH/11 (2021) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 11th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Articles 11, 12, 13, 14 and 23 of the European Social Charter for the period 01/01/2016 – 31/12/2019 Report registered by the Secretariat on 16 June 2021 CYCLE 2021 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND REFUGEES THE ELEVENTH REPORT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER /REVISED/ GROUP I: HEALTH, SOCIAL SECURITY AND SOCIAL PROTECTION ARTICLES 11, 12, 13, 14 AND 23 REFERENCE PERIOD: JANUARY 2016 - DECEMBER 2019 SARAJEVO, SEPTEMBER 2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 3 II. ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ........... 4 III. GENERAL LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ......................................................... 5 1. Bosnia and Herzegovina ............................................................................................... 5 2. Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina ....................................................................... 5 3. Republika Srpska ........................................................................................................... 9 4. Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina .............................................................. 10 IV. IMPLEMENTATION OF RATIFIED ESC/R/ PROVISIONS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA .............................................................................................. -

MAIN STAFF of the ARMY of REPUBLIKA SRPSKA /VRS/ DT No

Translation 00898420 MAIN STAFF OF THE ARMY OF REPUBLIKA SRPSKA /VRS/ DT No. 02/2-15 NATIONAL DEFENCE 31 March 1995 STA TE SECRET SADEJSTVO /coordination/ 95 VERY URGENT To the commands of the 1st KK /Krajina Corps/, IBK /Eastern Bosnia Corps/, DK /Drina Corps/, V /Air Force/ and PVO /Anti-aircraft Defence/ (to the 2nd KK /Krajina Corps/, SRK /Sarajevo-Romanija Corps/ and HK /Herzegovina Corps/, for their information). DIRECTIVE FOR FURTHER OPERATIONS, Operative No. 711 1. BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MILITARY AND POLITICAL SITUATION Since the start of the year, but particularly during the second half of March, Muslim armed forces have started wantonly violating in a synchronised manner the Agreement on a Four-month Cessation of Hostilities, focussing on offensive actions in the wider area of Bihac and Vlasic, in the zone of operations of the 30th Infantry Division and Task Group 2 of the 1st Krajina Corps, and on Majevica mountain, as well as regrouping and bringing in new forces to continue offensive actions in Posavina, towards Teslic and Srbobran. In synchronised activities, forces of the Muslim-Croatian Federation, forces of the HVO /Croatian Defence Council/ and units of the HV /Croatian Army/ are waiting for the result of the struggle on the Vlasic plateau and on Majevica, and in the event of a favourable development of the situation will join in with the aim of cutting the corridor and taking control of the Posavina, continuing operations in the direction of Glamoc and Grahovo, and, in cooperation with Muslim forces, taking Sipovo -

Bosnia-Hercegovina "Ethnic Cleansing"

November 1994 Vol. 6, No. 16 BOSNIA-HERCEGOVINA "ETHNIC CLEANSING" CONTINUES IN NORTHERN BOSNIA SUMMARY........................................................................................................................ 2 RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 4 Bosanska Krajina ................................................................................................... 4 The Bijeljina Region .............................................................................................. 6 ABUSES ............................................................................................................................. 7 Murders and Beatings ............................................................................................ 7 Torture.................................................................................................................. 15 Rape16 Disappearances 17 Evictions ................................................................................................................ 19 Forced Labor........................................................................................................ 20 Terrorization and Harassment .............................................................................. 27 Extortion ............................................................................................................. -

United Nations / Ujedinjene Nacije / Уједињене Нације International

United Nations / Ujedinjene nacije / Уједињене нације Office of the Resident Coordinator / Ured rezidentnog koordinatora / Уред резидентног координатора Bosnia and Herzegovina / Bosna i Hercegovina / Босна и Херцеговина International Humanitarian Assistance to BiH 29th May 2014 NOTE: This document represents compilation of data provided by listed embassies/organizations/institutions. The author is not responsible for accuracy of information received from outside sources. ORGANIZATION WHAT WHEN WHERE CATEGORY ADRA Current budget of 100,000 USD with Possibility of additional funding. 20/05/2014 Humanitarian aid, Full time local team to be emPloyed. WASH Early recovery Hundreds of volunteers engaged in PreParation and delivery of Doboj, Zavidovici, Vozuca, packages of food, water, hygiene items, clothes, infants’ utensils and Banja Luka, Bijeljina, medicines for PoPulation of affected areas. Samac and Orasje. Planed activities: Psychosocial support; Room dryers and 260dehumidifiers, expected to be here 26/05/2014. An engineer from Germany for one month; REDO water Purification unit (3,000l Per hour) will be shiPPed Doboj 26/05/2014; Debris Cleaning – Use of Effective Microorganisms (EM) to clean oil spills and other contaminations in and around houses, as well as rehabilitating agricultural land. Possible dePloyment of EM Expert Cleaning-up activities; Distribution of Relief Items; Technician for the Water distribution system and dryers 21/05/2014 Austria Since the beginning of the floods Austrian Humanitarian 28/05/2014 BIH Humanitarian -

Condition of the Cultural and Natural Heritage in the Balkan Region – South East Europe, Vol 2

CONDITION OF THE CULTURAL [ AND NATURAL HERITAGE IN THE BALKAN REGION Volume 2 Moldavia Slovenia Romania Croatia Serbia Bosnia and Hercegovina Montenegro Bulgaria Macedonia Albania Project REVITALISATION OF THE CULTURAL AND HERITAGE IN THE BALKAN REGION - South East Europe Project initiator and coordinator ICOM SEE - Working Group of ICOM Europe Partners National Committees of ICOM of Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia UNESCO Office in Venice - UNESCO Regional Bureau for Science and Culture in Europe (BRESCE) Co-partner National Museum in Belgrade CONDITION OF THE CULTURAL [ AND NATURAL HERITAGE IN THE BALKAN REGION Volume 2 Belgrade, 2011 Condition of the Cultural and Natural Heritage in the Balkan Region – South East Europe, Vol 2 Publishers: Central Institute for Conservation in Belgrade www.cik.org.rs Institute Goša d.o.o. www.institutgosa.rs Ministry of Culture of Republic of Serbia www.kultura.gov.rs Editors in chief: Mila Popović-Živančević, PhD, conservator-councillor Marina Kutin, PhD, Senior Research Associate Editor: Suzana Polić Radovanović, PhD, Research Associate, Central Institute for Conservation Reviewers: Prof. Kiril Temkov, PhD,Institute for Philosophy, Faculty of Philosophy, Skopje Prof. Simeon Nedkov, PhD, University Sveti Kliment Ohridski, Sofia Joakim Striber, PhD, Senior Researcher III, National Institute of Research-Development of Optoelectronics INOE, Romania Scientific Board: Prof. Denis Guillemard (France) Krassimira Frangova, PhD (Bulgaria) Jedert Vodopivec, PhD (Slovenia) Ilirjan Gjipali, PhD (Albania) Sergiu Pana, PhD (Moldova) Ljiljana Gavrilović, PhD (Serbia) Virgil Stefan Nitulescu, PhD (Romania) Donatella Cavezzali, PhD (Italy) Prof. Tomislav Šola, PhD (Croatia) Enver Imamović, PhD (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Davorin Trpeski, PhD (Macedonia) Editorial Board: Mila Popović-Živančević, PhD, ICOM Serbia Sabina Veseli, ICOM Albania Azra Bečević-Šarenkapa, MA, ICOM Bosnia and Herzegovina Prof. -

Itf-01-09/17-Dem/Ts-Bh-Usa

Based on the donations earmarked for the projects of Demining (DEM) and Technical Survey (TS) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, donated by Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement in the U. S. Department of State’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs through ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF), ITF would like to announce the following: WORKS PROCUREMENT NOTICE FOR EXECUTION OF DEMINING (DEM) AND TECHNICAL SURVEY (TS) WORKS 1. Publication reference: ITF-01-09/17-DEM/TS-BH-USA 2. Procedure: Open Tender Procedure for Commercial Companies and Non-governmental Organizations 3. Contracting Authority: ITF Enhancing Human Security (ITF) 4. Description of the contracts: Execution of Demining works on following contracts: ITF-01-03/17-DEM-BH-USA CONTRACT MACROLOCATION MICROLOCATION MAC ENTITY SURFACE TENDER SURVEY GUARANTEE NUMBE VALUE R ITF-01/17-DEM-BH-USA ITF-01A/17-DEM-BH-USA Doboj-Istok Lukavica Rijeka -Sofici 7625 FBiH 15.227 ITF-01B/17-DEM-BH-USA Orasje Kanal Vidovice 7673 FBiH 4.228 ITF-01C/17-DEM-BH-USA Lukavac Savičići 1B - Luka 10724 FBiH 6.285 ITF-01D/17-DEM-BH-USA Derventa Seoski put Novi Luzani-nastavak 53368 RS 5.769 31.509 1.300,00 USD ITF-02/17-DEM -BH-USA ITF-02A/17-DEM-BH-USA Olovo Olovske Luke 10403 FBiH 1.744 ITF-02B/17-DEM-BH-USA Visoko Catici 1 10010 FBiH 19.340 21.084 900,00 USD ITF-03/17-DEM -BH-USA ITF-03/17-DEM-BH-USA Krupa na Uni Srednji Dubovik 1 53053 RS 29.135 29.135 1.200,00 USD ITF-01-03/17-DEM -BH-USA TOTAL DEM 7 81.728 Execution of Technical Survey works on following contract: ITF-01-09/17-TS-BH-USA CONTRACT MACROLOCATION -

General Information About Mine Situation in B&H

Session 2 Second Preparatory Meeting of the OSCE 23rd Economic and Environmental Forum EEF.DEL/20/15 11 May 2015 ENGLISH only “BHMAC operational activities during and after last year natural disasters in BiH” Goran Zdrale, BHMAC Belgrade, 11 - 13 May 2015 General information about mine situation in B&H ¾ Mine suspect area is 1.170 km2 or 2,3% of total area of BiH ¾ Estimated approximately 120.000 pieces of mine/UXO remained ¾ Total 1.417 affected communities under the impact of mines/UXO ¾ Approximately 540.000 citizens affected, or 15% of total population ¾ In post-war period /after 1996/, there were 1.732 victims, 603 of them fatalities Impact of floods and landslides on mine suspect areas – General assessment ¾Flooded area: 831,4 km2 ¾ Mine suspect area in flooded areas: 48,96 km2 ¾ No. of communities: 36 ¾ No. of communities: 106 ¾ No. of landslides at/near mine suspect areas: 35 ¾ Critical points: active landslides, river beds, river banks and areas flooded by water level above 1m ¾ Large amounts of remaining UXO and SALW ¾Mine danger signs have been shifted away or destroyed Media Campaign ¾ Comprehensive media campaign conducted to warn and inform citizens and volunteers ¾ Published daily announcements for the public at www.bhmac.org ¾ In cooperation with UNDP, continuously presented mine situation maps http://un.ba/stranica/floods-in-bih ¾ 1 theme press conference organised and cooperation established with over 40 national and international media agencies MINE/UXO Awareness ¾ UNDP and EUFOR provided over 10.000 leaflets for distribution as a warning about mine threat ¾ Intervention teams for Mine Awareness warned over 15.000 citizens and volunteers ¾ Intervention teams for Mine Awareness placed or renewed approximately 2.200 mine warning signs MINE/UXO Awareness No.