Understanding How Foreign Cultures Respond to Missionary Aviation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2010 Dearwheaton

This version of Wheaton magazine does not contain the Class News section. s p r i n g 2 0 1 0 WHEATON The Litfin Legacy Continuity Amid Growth President Duane Litfin retires after 17 years Inside: Science Station Turns 75 • Remembering President Armerding • The Promise Report 150.WHEATON.EDU Wheaton College exists to help build the church and improve society worldwide by promoting the development of whole and effective Christians through excellence in programs of Christian higher education. This mission expresses our commitment to do all things “For Christ and His Kingdom.” volume 14 i s s u e 2 s PR i N G 2 0 1 0 6 a l u m n i n e w s departments 32 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters Open letter from Tim Stoner ’82, 5 News president of the Alumni Board 10 Sports 33 Wheaton Alumni Association News Association news and events 27 The Promise Report 37 Alumni Class News 56 Authors Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts from published alumnus Walter Wolfram ’63 Cover photo: President Litfin enjoys the lively bustle of the Sports and A Sentimental Journey Recreation Complex that was built in 2000 as a result of the New 58 Century Challenge. The only “brick-and-mortar” part of that campaign, An archival reflection from an alumna the SRC features a large weight room, three gyms, a pool, elevated Faculty Voice running track, climbing wall, dance and fitness studio, and wrestling 60 room, as well as classrooms, conference rooms, and a physiology lab. Dr. Nadine Folino-Rorem mentors biology Dr. -

July/August 2020

VOL. 6 • NO. 6 • JULY/AUGUST 2020 Umpire Martez Thomas sanitizes a baseball between innings during a youth baseball tournament in Cottleville, Missouri. (AP Photo) 6WT20_01_Cover.indd 1 6/11/20 9:56 AM THAT’S WHY WE GIVE YOU THE FREEDOM TO HAND-PICK YOUR TEACHERS. WWW.KEPLER.EDUCATION CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN EDUCATION FOR JUNIOR HIGH AND HIGH SCHOOL. NOW ENROLLING FOR SUMMER 2020 & FALL 2020-2021 CLASSES. 6WT20_2,31,32_Ads.indd 2 6/11/20 12:12 PM JULY/AUGUST 2020 • VOL. 6 • NO. 6 The price Talking Poachers and Ready for of working 6 about tacos 11 13 14 COVID-19 sports? from home Saying How clouds Well-bred goodbye to save 16 20 bread 22 24 Mincaye Spotting shipwrecks coral Splattered with color, this image of the Moon materials,” says geologist James Skinner. looks like it lost a paintball game! But the The Unified Geologic Map of the Moon, as it colors you see are part of a code. This isn’t an is called, was released on April 20. Making The near side (right) and artist’s painting. It’s the most comprehensive the map required data from six di erent the far side Moon map ever made. Each color represents Apollo Moon missions as well as new of the Moon. a feature of the Moon’s surface. “The darker, submissions by recent spacecra . The U.S. more earth tones are these highland-type Geological Survey based in Flagsta , terrains, and the reds and the purples tend Arizona, is responsible for the out-of-this- to be more of these volcanic and lava flow world map. -

Author Description Price

Index Category Page Bibles 1-2 Bible Versions 3 Biographies 3-9 Booklets & Tracts 9-15 Charismatic Movement 15 Children’s Books 15-29 Christian Apologetics 29-30 Christian Life 30-41 Church History & The Reformation 41-45 Collected Writings 45-48 Commentaries 48-54 Creation & Evolution 54-57 Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland Daily Readings 57-58 Doctrine & Theology 58-66 Bookroom Other Religions, Heresies & Cults 66-67 Rome 67 133 Woodlands Road Study Aids 58-70 GLASGOW G3 6LE CDs/DVDs/Videos 70-71 Tel: 0141 332 1760 Fax: 0141 332 4271 Works 71-82 Please Note: The prices listed in this catalogue are subject to change without notice. E-mail : [email protected] We will however, do our best to keep the change to a minimum. Books Website: www.fpbookroom.org may also become unavailable. For the latest titles check www.fpbookroom.org (Books are listed alphabetically by title, unless otherwise stated) All Prices listed are in £ Sterling 25A Vinyl covered hardback 7.95 TBS Double Pica Four Volume Bible page size 9" x 5½" (very large print) Bibles 70A Vinyl boards. Head & tail bands (4 volume set) 48.75 Individual Volumes 14.50 TBS with Metrical Psalms: TBS Large Print Bible page size 10¾" x 8¼ BLP Flexible cover, presentation page 25.00 PS31A Vinyl boards, head & Tail bands 7.00 PS31B Bonded leather, semi-yapp, art gilt edges (slip-case) 19.95 1A Comfort Text Bible page size 9¾" x 6¼" Windsor Text Bible page size 7½" x 5¼" Large print with vinyl boards & marker ribbon 16.50 PS25A Vinyl boards, head & tail bands 10.50 PS25U Calfskin Leather, semi-yapp, art gilt edges. -

Operation Auca Was an Attempt by Five American Missionaries to Bring the Gospel to the Waorani People in Ecuador

Operation Auca was an attempt by five American missionaries to bring the Gospel to the Waorani people in Ecuador. On January 8, 1956, all five men—including Jim Elliot and Nate Saint, —were attacked and speared by a group of Waorani warriors. A few years later, the widow and young daughter of Jim Elliot, Elisabeth & Valerie, and the sister of Nate Saint returned to the same jungle tribe as missionaries, eventually leading to the conversion of many. Gather a group together and come hear Valerie Elliot Shepard, the daughter Elisabeth Elliot, and her husband, Walt Shepherd, speak in Orange City on November 2 & 3, with a men’s breakfast event ($5, 9-10:30 AM) and women’s conference ($10, 9 AM -2 PM , lunch included). Get your tickets before prices go up this Tuesday, the 15th! Visit your local Radio Shack or shepards.eventbrite.com by TOMORROW night. Also mark your calendar for the free session Friday night, Nov. 2nd at the Unity Knight Center from 7-8:30; free-will offering Email [email protected] with any questions. These events are sponsored by OC area churches, businesses and community members. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - But, What Would Jesus Do (WWJD), about Immigration? An Insightful and Inspirational Event worth attending! Hear Dr. Jason Lief of Northwestern College speak on the history of immigration & unpack misconceptions. Hear life stories of Dreamers Not taking political positions, just considering, What Would Jesus Do? Tuesday, October 30 7:00PM Sioux Falls Ministry Center, 225 E. 11th St., Sioux Falls, South Dakota - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - The annual Katelyn’s Fund Orphan Ministry Auction, scheduled for November 2, is receiving monetary and merchandise donations. -

Through Gates of Splendor Book Discussion Guide

Through Gates of Splendor Book Discussion Guide Chapter I: “I Dare Not Stay Home” Describe Jim Elliot. What was he like? What were some of the life experiences that shaped Jim into the man he was? How did Jim know that God wanted him to spend his life as a missionary in Ecuador? What kind of man was Pete Fleming? Pete Fleming wrote, “A call is nothing more nor less than obedience to the will of God, as God presses it home to the soul by whatever means He chooses” (page 22). Can you think of any times when you were absolutely sure of the will of God? What are some ways we can make ourselves more open to hearing God’s voice? Chapter II: Destination: Shandia Before you began to read this book, what did you know about the life and culture of Ecuador? Which elements of Ecuadorian culture do you think were most appealing to the missionaries? Which posed challenges? Based on the brief historical sketch of Ecuador given in this chapter, what might have been some of the Ecuadorians’ assumptions about foreigners, and vice versa? Chapter III: “All Things to All Men” The portrait of Venancio (pages 41-42) describes the daily life of a typical Quichua native. How does this compare with daily life where you live? In what ways does the Quichua birthing experience (pages 43-45) differ from a typical Western birth? What do you think this story signifies about Quichua attitudes toward children and family life? Toward medicine? Why is it so important—beyond basic communication—for missionaries to become as fluent as possible in the native language of those they are trying to reach? Chapter IV: Infinite Adaptability Describe Ed McCully. -

Newsletter Jan 2021

JANUARY 2021 NEWSLETTER Christ followers in low-tech environments (low-tech does not Why ITEC Exists mean low intelligence), training Christ followers to meet felt needs as a door opener for the Gospel, and equipping others to do the by Jaime same (both domestically and globally). A number of years ago, a couple was visiting ITEC as part of the This interdependent relationship with our Christian brothers and process to determine if God was calling them to be a part of our sisters around the world is the vision that continues to drive ITEC team. At the end of the week, they came into my office and asked today. The Great Commission was given to every Christ follower, what they would do if they were to move across the country to and there is a role for every Christ follower to play. join us. I explained that prayerfully considering and submitting to God whether they felt called to work at ITEC was the first thing we Each of us has been given gifts to be used to further this mission. needed to be sensitive to. Then, as long as their calling to ITEC Romans 12:4-8 says, “For just as each of us has one body with was confirmed, we could begin to discuss the unique role God many members, and these members do not all have the same had them to play on our team. function, so in Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others. We have different ITEC was started on the principle that every Christ follower has a gifts, according to the grace given to each of us. -

537E34d0223af4.56648604.Pdf

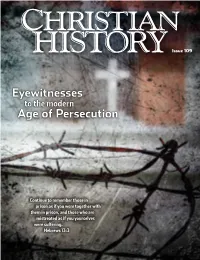

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 109 Eyewitnesses to the modern Age of Persecution Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering. Hebrews 13:3 RARY B I L RT A AN M HE BRIDGE T COTLAND / S RARY, B I L RARY B NIVERSITY I U L RT A AN LASGOW M G “I hAD TO ASK FOR GRACe” Above: Festo Kivengere challenged Idi Amin’s killing of Ugandan HE BRIDGE Christians. T BOETHIUS BEHIND BARS Left: The 6th-c. Christian ATALLAH / M I scholar was jailed, then executed, by King Theodoric, N . CHOOL (14TH CENTURY) / © G an Arian. S RARY / B TALIAN I I L ), Did you know? But soon she went into early labor. As she groaned M in pain, servants asked how she would endure mar- CHRISTIANS HAVE SUFFERED FOR tyrdom if she could hardly bear the pain of childbirth. , 1385 (VELLU She answered, “Now it is I who suffer. Then there will GOSTINI PICTURE A THEIR FAITH THROUGHOUT HISTORY. E be another in me, who will suffer for me, because I am D HERE ARE SOME OF THEIR STORIES. also about to suffer for him.” An unnamed Christian UM COMMENTO woman took in her newborn daughter. Felicitas and C SERVING CHRIST UNTIL THE END her companions were martyred together in the arena Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, is one of the earliest mar- in March 202. TALY, 16TH CENTURY / I tyrs about whom we have an eyewitness account. In HILOSOPHIAE P E, M the second century, his church in Smyrna fell under IMPRISONED FOR ORTHODOXY O great persecution. -

Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF)

MAF Youth School Resources www.maf-uk.org/school Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) MAF is a dynamic Christian aviation charity that flies over deserts, jungles and mountains, bringing help, hope and healing to the most isolated communities on earth. With a fleet of 135 light aircraft, we partner with over 1,500 other organisations such as Oxfam, Tearfund, the BBC, Save the Children and WaterAid, flying them to remote areas of the world, where access would either be impossible or would take days of arduous overland travel. MAF uses planes to transform the lives of the world’s most isolated people. Scheme of work introduction This resource, written specially for Religious Education teachers, features a selection of lesson plans and resources based around the story of the inspirational Christian martyr Nate Saint, an MAF pilot in the 1950s. It has been designed to meet the requirements of the Religious Education curricula for England and Wales. This scheme of work is based on Nate Saint’s exciting story. He flew as an MAF pilot in the 1950s, but was brutally martyred – along with four other missionaries – as they attempted to reach out to one of the world’s deadliest tribes in the Ecuadorian rainforest at risk of extinction. This inspirational story, brought to life through the lesson plans, is designed to explore, question and unpack the following themes: • Christian commitment to serving, worshipping and self-sacrifice • The incredible power of love, forgiveness and repentance • Inspirational Christians • Justice and fairness • Life after death • Martyrdom • Moral and ethical choices • Christian response to global issues worldwide. -

243966 Bridge Downld

BRIDGE OF BLOOD Jim Elliot Takes Christ to the Aucas Cast: ELISABETH: narrator of the play JIM: Elisabeth’s husband HOST: may be worship leader or pastor R1: male who portrays: Nate Saint; student body president R2: female who portrays: Marj Saint; Mrs. Shuell R3: male who portrays: Pete Fleming; college student R4: female who portrays: Olive Fleming; Miriam Shuell R5: male who portrays: Ed McCully; Wayne; Mr. Shuell R6: female who portrays: Marilou McCully; Dayuma R7: male who portrays: Roger Youderian; preacher R8: female who portrays: Barbara Youderian This cast list is the recommended assignment of parts. If a larger cast is de- sired, simply divide the parts further. Props: Metal stools for each cast member DO NOT PRINT Sound Notes: SAMPLE Organ music is needed. “Nothing Between My Soul and My Savior” is recommended, as well as “Be Still, My Soul.” Stage Arrangement: Diagrams appear throughout the script indicating actors’ positions. The following symbols are used: —Stools ̅—Actor’s back to audience ̃—Actor facing audience Ȇȇ—Actors move as per direction of arrows. Also indicates how stools are moved. Copyright © 1988 and 1996 by Lillenas Publishing Co. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States. www.lillenasdrama.com 5 ACT ONE (Blackout—all performers come to the stage, strike strong action poses, and then “freeze.” The cast will again be in this exact stage picture for the final scene before the men leave to set up camp at “Palm Beach,” the location of their deaths.) (Lights up) R2: Excuse me, Ed (R3, R5, and R7 are looking at map on floor), would you care for a brownie? R3: No thanks, Marj. -

Visions of the Ecuadorian Amazon Matthew Ford State University Of

Vol. 18, Num. 2 (Winter 2021): 63-91 Indelible Divides and the Creation of Myths: Visions of the Ecuadorian Amazon Matthew Ford State University of New York—Stoney Brook Indelible Divides and the Creation of Myths: Visions of the Ecuadorian Amazon In 2018, the late anthropologist Stephen Nugent noted that Amazonia, “perhaps more than any other region of the globe, has consistently been idealized and mythologized. This is true both of its societies, often envisioned as ‘lost tribes in the forest,’ and the ‘raw green hell’ of its environment.”1 In many ways, we all know the common mythical images associated with the Amazon: the region that time left behind; the place where stone-age people continue to live; the green heart and hell of South America where western civilizing missions go to die. This mythic vision is strong and reeks of colonialist obsessions with the “backward” racial Other. Nugent went on to argue that, despite rigorous historical research, the Amazon “is so well known through an apparatus of mythic redundancy and hyperbolic, naturalistic excess that attempts to dismantle the stereotypes are largely ineffective.”2 Indeed, despite the countless efforts 1 Stephen Nugent, “Stop Mythologizing the Amazon—It Just Excuses Rampant Commercial Exploitation,” The Conversation, 15 February 2018. https://theconversation.com/stop-mythologising-the-amazon-it-just-excuses-rampant- commercial-exploitation-91343. [accessed 14 November 2018]. 2 Stephen L. Nugent, The Rise and Fall of the Amazon Rubber Boom: An Historical Anthropology (New York: Routledge, 2018), 1. Ford 64 to historicize Amazonia and its people, images of timelessness persist in both popular and academic constructs of the region. -

Author Description Price

Index Category Page Bibles 1-3 Bible Versions 3 Biographies 4-10 Booklets & Tracts 10-17 Charismatic Movement 17 Children’s Books 17-30 Christian Apologetics 30-31 Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland Christian Life 31-42 Bookroom Church History & The 42-46 Reformation 46-48 133 Woodlands Road Collected Writings GLASGOW G3 6LE Commentaries 49-55 Tel: 0141 332 1760 Creation & Evolution 55-57 Daily Readings 57-59 Doctrine & Theology 59-67 Other Religions, Heresies & 67-68 E-mail: Cults [email protected] Rome 68 [email protected] Study Aids 69-71 Website: CDs/DVDs 71-72 http://www.fpchurch.org.uk/free-presbyterian-bo Works 72-83 okroom/ Please Note: The prices listed in this catalogue are subject to change without notice. We will, however, do our best to keep the change to a minimum. Books may 60ACB Compact Hardback, Coloured Photograph on Cover 12.95 also become unavailable. (Books are listed alphabetically by title, unless otherwise stated) All Prices listed are in £ Sterling Bibles Compact Westminster Reference Bible, page size 6.5" x 4.6", print size 7.3 point 60S/R Burgundy Softback 9.95 Bibles with Metrical Psalms : 60A/BK,BL,R Hardback- Black, Blue, Red 11.50 PS4U/BK Classic Reference Bible Black Calfskin Leather 49.95 Pocket Reference Bible, page size 5.2" x 3.6", print size 5 point PS90U/BK Westminster Reference Bible Black Meriva Leather 89.95 PS60U/BK Compact Westminster Reference Bible Black Meriva Leather 69.95 7S/R,GY Vinyl Paperback- Burgundy, Soft Grey 4.75 PS7U/BK Pocket Reference Bible Black Calfskin 41.95 7U/R Burgundy -

God Has Blessed All of Us with Gifts and Talents of Some Kind, and We

Fall 2013 a Financial and charitable estate planning guide FOR HONOR AND BLESSING The loss of a loved one is always heartbreaking, but the Allen Swan family found a way to perpetually honor the memory of their beloved wife and mother and turn their sadness into an ongoing blessing for others. Lydia (Janke ’48) Swan studied at Northwestern’s campus in downtown Minneapolis under the presidency of a young Billy Graham. She studied nursing at Swedish Hospital in order to become a Registered Nurse in 1952. She then married Allen Swan. In 1980–81, the Swans' youngest son, Phillip, attended Northwestern. Today Phillip serves as associate professor of music and co-director of Choral Studies at Lawrence University. Their LYDIA (JANKE '48) SWAN oldest son, Dr. Timothy Swan, is an Interventional Radiologist in Marshfield, Wisconsin. Two of Tim’s daughters have already graduated from Northwestern and his third daughter will graduate in the first class of Northwestern’s new nursing “God has blessed all of us program in August 2014. with gifts and talents of Although Lydia passed away in 1996, her life some kind, and we have continues to have impact in the form of an endowed scholarship established by her husband and sons a responsibility to share in her honor. Each year the scholarship is awarded those gifts with others.” to a Northwestern student studying music or medicine—areas of close interest to the Swan family. —Allen Swan “I’m very thankful to the Swan family for their generosity,” says two-time CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1 scholarship have as they pass on what they’ve learned that Allen’s former recipient Miriam (Mick ’08) learned to those they serve in employer, General Mills, would Camarse.