An Interview with Paulette Bourgeois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paulette Bourgeois Entitled: the Inside Story of Franklin the Turtle: from Book to Brand

The Master of Arts in Children’s Literature Program Presents: A talk by one of Canada’s most beloved children’s book writers Paulette Bourgeois Entitled: The Inside Story of Franklin the Turtle: From Book to Brand Thursday, January 26th, 2012, 4:30 – 5:30 pm The Dodson Room, Room 302, Level 3, Chapman Learning Commons, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, 1961 East Mall, University of British Columbia Refreshments served Paulette Bourgeois is one of Canada’s most noted and Paulette Bourgeois is best-known for creating Franklin beloved picture book creators. She is the author of scores the Turtle, the character who appears in picture books of picture books and nonfiction books and the creator of illustrated by Brenda Clark. The books have sold more the Franklin the Turtle series, beginning with Franklin in the than 60 million copies and have been translated into 38 Dark, illustrated by Brenda Clark. The series is a landmark languages. An animated television series, merchandise, in Canadian publishing for children. It has sold more than DVDs and full-feature movies are based on the character. 60 million books in 38 languages. The licensed character She is also the author of award-winning books for children of Franklin has his own animated television series, seen in including Oma’s Quilt which was developed as a short over 15 countries. Paulette Bourgeois will discuss her 25- film by the National Film Board of Canada, and more than year experience in the creation of the series, and what it two dozen non-fiction science books. She is a member of has been like to participate in and watch Franklin transform the Order of Canada, has received an honorary doctorate from book to brand. -

36Th Annual Language Arts Conference

2012 36th Annual Language Arts Conference Thursday, February 9th and Friday, February 10th Sheraton Centre Hotel 123 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario Registration Information/Form PAULETTE BOURGEOIS WES “MAESTRO” WILLIAMS JOSEPH BOYDEN KATHRYN OTOSHI ERIN GRUWELL THURSDAY BREAKFAST SPEAKER THURSDAY LUNCHEON SPEAKER THURSDAY BANQUET SPEAKER FRIDAY BREAKFAST SPEAKER FRIDAY LUNCHEON SPEAKER Celebrate Reading at our 36th Anniversary … Inspirational Keynote Speakers … JOSEPH BOYDEN Awards Banquet Speaker Walk to Morning: Stories From a Writer’s Life Joseph Boyden is a Canadian novelist and short story writer. A Canadian with Irish, Scottish and Métis roots, Joseph writes about First Nations heritage and culture. An international bestseller that has been translated into 15 languages, his first novel, Three Day Road, has won a multitude of awards including the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, the McNally Robinson Aboriginal Book of the Year Award, and the Canadian Authors Association Book of the Year Award. Three Day Road was also shortlisted for the Governor General Award for Fiction. Boyden’s second novel, Through Black Spruce, was the 2008 winner of Canada’s most prestigious literary prize, the Scotiabank Giller Prize. He is the author of Born with a Tooth, a collection of stories that was shortlisted for the Upper Canada Writer’s Craft Award. Boyden is a contributing writer for Canada’s Maclean’s and Zoomer magazines and has published fiction and nonfiction in a variety of places, including Walrus, Driven, and Globe and Mail. His work has also appeared in publications such as Potpourri, Cimarron Review, Blue Penny Quarterly, Black Warrior, and The Panhandler. PAULETTE BOURGEOIS The Ten Best Things About Franklin the Turtle Paulette Bourgeois is best-known for creating Franklin the Turtle, the character who appears in picture books illustrated by Brenda Clark. -

Franklin and Friends Musical Comes to the Performing Arts Center Nov. 10

Skip to Content Cal Poly News Search Cal Poly News Go California Polytechnic State University Oct. 23, 2002 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: LISA WOSKE (805) 756-7110 Franklin and Friends Musical Comes to the Performing Arts Center Nov. 10 SAN LUIS OBISPO - "Franklin's Class Concert," the delightful full-length musical production that features Franklin the Turtle and his friends Fox, Beaver, Bear and Snail, comes to life on the Christopher Cohan Center stage at 6 p.m. on Sunday, November 10. (Please note special curtain time.) Cal Poly Arts presents the original musical as part of their popular, low-cost Family Series. "Franklin's Class Concert" is produced by Tanglewood Productions, who helped bring the successful "Little Bear Live on Stage" show to San Luis Obispo family audiences during the Cal Poly Arts 2001/02 season. The show features Franklin and pals Fox, Beaver, Bear, and Snail in a lively show filled with non-stop singing, dancing and audience participation. In the story, it's time for the annual class concert. Everyone will perform a special number, but Franklin fears that he has no talent. Just when he thought things couldn't get worse, the concert happens earlier than expected. What will happen when Beaver suffers from stage fright, Snail can't hit the high note, and Fox is unable to make someone reappear after they disappear in his magic act? Audiences of all ages will enjoy finding out. Since the first book, "Franklin in the Dark," was published in 1986, the character of Franklin has gained worldwide fame. -

CAOT Conference 2009 Congrès De L'ace 2009

CAOT Conference 2009 On-Site Guide Congrès de l’ACE 2009 Guide du Congrès Contents • Sommaire Ottawa • ON • June 3-6 juin 2 Message from the Premier 3 Message from the Mayor • Message du maire 4 Welcome from the President and Executive Director of CAOT Mot de bienvenue de la présidente et de la directrice générale de l’ACE 5 Welcome from the OSOT President • Mot de bienvenue de la présidente de l’OSOT 6 Welcome from the Host Committee Co-Convenors Official publication of the Canadian Mot de bienvenue des co-directeurs du comité d’accueil Association of Occupational Therapists 7 Welcome from the Scientific Program Committee 2009 • Mot de Publication officielle de l’Association bienvenue du comité du programme scientifique du Congrès 2009 canadienne des ergothérapeutes 8 Keynote Speaker • Rachel Thibeault • Conférencière d’honneur Executive Director Directrice générale 10 Muriel Driver Memorial Lecturer • Nicol Korner-Bitensky • Conférencière Claudia von Zweck du discours commémoratif Muriel Driver CAOT Conference Steering Committee 12 Plenary Speaker • Paulette Bourgeois • Conférencière de la Comité organisateur du congrès séance plénière Mary Manojlovich Cathie Kissick 13 Special Events • Événements spéciaux Jean-Pascal Beaudoin 16 Forums and Sponsored Sessions • Forums et séances parrainées Christina Hatchard Cheryl Evans 19 Session Information • Information sur les séances Lisa Sheehan 19 Conference at a Glance • Coup d’œil sur le congrès Claudia von Zweck 21 Detailed Program • Programme détaillé 21 Thursday, June 4 • Jeudi le 4 juin 37 Friday, June 5 • Vendredi le 5 juin Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to/Retourner les colis non distribuables 49 Saturday, June 6 • Samedi le 6 juin portant une adresse canadienne à l’adresse suivante : 55 Exhibit Floor Plan • Plan du Salon professionnel CAOT/ACE CTTC Building 56 Exhibitor Descriptions • Liste des exposants 3400-1125 Colonel By Dr Ottawa ON K1S 5R1 Canada 61 Sponsors • Répondants Tel. -

On Your Marks, Get Set, Campaign

The Pickering 50 PAGES ✦ Metroland Durham Region Media Group ✦ WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2004 ✦ Optional delivery $6 / Newsstand $1 BACK HOME EXTRA ZIP MIXED RESULTS Illustrator returns Pickering juniors Mazda adds to Pickering roots to its zoom win one, drop two Entertainment 8 Wheels pullout Sports 9 [ Briefly ] Carib cultural group marks 24 years : Celebrate 24 years of fun and fellowship next Murder claims all lies: Hall month with The Pickering Carib Canadian Cultural Association. The group holds an anniver- Co-accused says his long-time friend Cosmo Jacobson Paul Burstein. “I was just trying to shooting of Mr. Jones. Crown coun- sary dinner and dance Saturday, of first-degree murder in the killing show that I was an experienced crimi- sel Paul Murray says Mr. Hall was the Oct. 16 at the Pickering Recreation he was ‘bigging up’ of Ajax resident Roy Jones, who was nal. wheel man who drove away from the Complex. The event features din- ner with wine, music from a disc to impress ‘bikers’ gunned down days before he was to “All that stuff I was talking about was crime scene, eluding oncoming police jockey, door prizes and a cash bar. testify against Mr. Jacobson in court. lies.” cruisers, after Mr. Jacobson chased Mr. The cocktail hour starts at 6:30 Mr. Hall said that, even though he’s Mr. Hall said that he had heard it Jones down and shot him. By Jeff Mitchell p.m., followed by dinner at 7:30 heard and seen on secretly recorded was Mr. Jacobson and two members Mr. -

Franklin: Ideal Children's Literary Idol Or Flavourless Turtle of Privilege?

Profile: Franklin: Ideal Children's Literary Idol or Flavourless Turtle of Privilege? Leanne Wild • Brenda Clark Resume: Ce court article analyse Ie succes de la serve Franklin la Tortue. L'autew examine la dimension didactique et cultwelle de la production ainsi aue les caracteristiques essentielles du personnage. Une etude des illustrations de Brenda Clark etaye son analyse. Summary: This profile examines Franklin the turtle's rise to fame. Leanne Questions the socializing and didactic value of the Franklin books, as well as the uniqueness and substance of Franklin himself. An interview with illustrator Brenda Clark forms part of the analysis, and the significance of the illustrations, character, story and pedagogy of the Franklin phenomenon are discussed. /7/e's a small green guy with a shell, and he's made his way into the spotlight Jl, of the Canadian — and now North American — children's literary scene. On a Saturday in mid-April, children gather in a Mississauga Chapters store to meet Franklin the turtle and hear one of his stories read. Franklin's visits — to bookstores, libraries, schools and even restaurants — have become so frequent that Kids Can Press has designated a staff member to co-ordinate the booking of the turtle's official costume. 38 Canadian Children's Literature I Litterature canadimne pour la jeunesse • Franklin's stats are impressive: 16 million books sold worldwide, an animated TV series with The Family Channel and CBS (beginning fall 1998), a myriad of toys, figurines and stickers. Activity books and CD-ROMs geared towards developing math and reading skills, and inspired artistic partnerships such as that with the Touring Players Theatre of Canada, whose Franklin shows, performed largely for schools, have joined the Players' Robert Munsch-based plays as their best-selling shows. -

Programme 2012

2012 36th Annual Language Arts Conference Thursday, February 9th and Friday, February 10th Sheraton Centre Hotel 123 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario Programme PAULETTE BOURGEOIS WES “MAESTRO” WILLIAMS JOSEPH BOYDEN KATHRYN OTOSHI ERIN GRUWELL THURSDAY BREAKFAST SPEAKER THURSDAY LUNCHEON SPEAKER THURSDAY BANQUET SPEAKER FRIDAY BREAKFAST SPEAKER FRIDAY LUNCHEON SPEAKER 2012 36th Annual Language Arts Conference Thursday, February 9th and Friday, February 10th Table of Contents Map of Sheraton Centre Meeting Rooms. 4 Conference Session Planner — Personal Sessions Choices . 6 Schedule of Events. 7 Index of Presenters. 8 Thursday at a Glance. 10 Friday at a Glance . 12 Speaker Sessions and Profiles (listed Alphabetically) . 14 Paulette Bourgeois Thursday Breakfast Speaker . 15 Joseph Boyden Thursday Banquet Speaker . 16 Erin Gruwell Friday Luncheon Speaker . 22 Kathryn Otoshi Friday Breakfast Speaker . 35 Wes “Maestro” Williams Thursday Luncheon Speaker . 45 Map of Exhibit Floor . 46 Board of Directors . 47 Message from the President Dear Delegates: Welcome to the 36th annual Reading for the Love of It conference. Whether you are a first-year attendee, or returning for the 36th time, I hope the days ahead provide you with an opportunity to reconnect, restore, and reflect. Our annual conference is a time for educators, writers and researchers to reconnect with colleagues from near and far. Reading for the Love of It provides a much needed chance to recharge as we learn about new strategies and teaching ideas. It also affords us time for reflection; to read, write, think and talk about our own learning and our professional practice. I hope that this year’s conference provides you with an opportunity for all of this. -

Annual Impact Report Contents

2012/2013 ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT CONTENTS 3 Year at a Glance 4 Violence Prevention 10 Empowering Girls 14 Economic Development 18 Ending Human Trafficking 22 Statement of Revenue and Expenses 24 Board of Directors 24 Volunteer Committees 28 Endowment Fund 29 Individual Donors 37 Corporate and Community Supporters OUR VISION Invest in women and girls. Change everything. OUR MISSION We invest in the strength of women and the dreams of girls. The Canadian Women’s Foundation raises money to end violence against women, move women out of poverty and build strong resilient girls through funding, researching and promoting best practices. We are a leading voice for women in Canada. 2 Thanks to you “ Last year we invested $7,571,295 to help women and girls in Canada move out of violence, out of poverty, and into confidence. You supported ground-breaking programs that address the most critical challenges facing women and girls in Canada. Because of you, women and girls have the help they need to transform their lives, right in their own communities. With your help, the Canadian Women’s Foundation is making a profound difference in the lives of thousands of women and girls across Canada.” – MINA MAWANI, PRESIDENT AND CEO, CANADIAN WOMEN’S FOUNDATION YEAR AT A GLANCE Total amount invested Number of 122 447 $7,571,295 initiatives Major Shelter Grants Grants Investment in training, research, Number and development 8,835 $2,163,687 of donors Number of volunteers 672 Investment in community grants $5,407,608 3 VIOLENCE PREVENTION HAYDEE, Burnaby, BC We believe every woman has the right to live free from violence. -

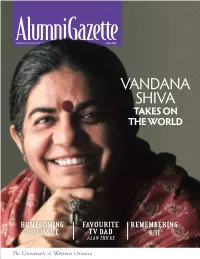

Vandana Shiva Take S on the World

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRINGFALL 20102011 VANDANA SHIVA TAKE S ON THE WORLD HOMECOMING FAVOURITE REMEMBERING 2011 ISSUE TV DAD 9/11 ALAN THICKE AlumniGazette CONTENTS COUD L ALAN THICKE 11 BE THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE TV DAD? Profile of multi-talented Western alumnus BY JASON WINDERS, MES’10 S EEDS OF THE FUTURE 12 Vandana Shiva, PhD’79, LLD’02, takes on the world BY JASON WINDERS, MES’10 REMEMBERING 9/11, 14 10 YEARS LATER Reflections of Western alumni who experienced the attack You don’t need a better F ROM BOARDROOMS 20 TO BODICES… Beverly Behan, HBA’81, LLB’84, Financial Advisor. makes Canada’s history sexy BY DAVID SCOTT You need a great one. ALLE IN TH FAMILY 22 Western’s multi-generation graduates BY DAVID DAUPHINEE Like any great relationship, this one takes Just log on to www.accretiveadvisor.com hard work. and use the “Investor Discovery™” to On the cover: Indian philosopher, environmental activist and lead you to the Financial Advisor who’s eco-feminist Vandana Shiva, PhD’79, LLD’02, has made her Choosing the right Advisor is the key to best for you and your family. impact around the world. (Photo by Nitin Rai) a richer life in every way. 12 After all, the only thing at stake here But to get what you deserve, you need DEPARTMENTS is the rest of your financial life. alumnigazette.ca to act. Right now wouldn’t be a moment @ 05 LETTERS 33 MEMORIES WINNIPEG’S RETURN TO NHL HOCKEY too soon. www.accretiveadvisor.com H onour Society existed T radition of pranks keeps By Edward Fraser, BA’03, MA’04, Managing Editor, The Hockey News before 1952 campus on its toes BY ALAN NOON CYBORG TRADING SYSTEMS PRODUCES 08 CAMPUS NEWS SOFTWARE FOR HIGh-FREQUENCY TRADERS Labatt’s history home at 34 NEW RELEASES By Christopher Clark BA’88, MA’92 Western archives T he White Luck Warrior by T HOU DOTH PROTEST: PEACEFUL PROTEST OR R. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Franklin's Bad Day by Paulette Bourgeois Search Abebooks

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Franklin's Bad Day by Paulette Bourgeois Search AbeBooks. We're sorry; the page you requested could not be found. AbeBooks offers millions of new, used, rare and out-of-print books, as well as cheap textbooks from thousands of booksellers around the world. Shopping on AbeBooks is easy, safe and 100% secure - search for your book, purchase a copy via our secure checkout and the bookseller ships it straight to you. Search thousands of booksellers selling millions of new & used books. New & Used Books. New and used copies of new releases, best sellers and award winners. Save money with our huge selection. Rare & Out of Print Books. From scarce first editions to sought-after signatures, find an array of rare, valuable and highly collectible books. Textbooks. Catch a break with big discounts and fantastic deals on new and used textbooks. Franklin's Bad Day. Today Franklin wakes up grumpy. His father discovers the reason for Franklin's crankiness--Otter has moved away and nothing seems right without her. Comforted by a hug from Dad, Franklin cheers up and makes a special present to mail to Otter, who is only a letter or phone call away. Full color. Read More. Today Franklin wakes up grumpy. His father discovers the reason for Franklin's crankiness--Otter has moved away and nothing seems right without her. Comforted by a hug from Dad, Franklin cheers up and makes a special present to mail to Otter, who is only a letter or phone call away. Full color. Read Less. ISBN 13: 9781554537327.