The Threepenny Opera (Rec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2016

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2016 High-brow, Low-brow, All-brow Bernstein, Gershwin, Ellington, and the Richness of American Music © VICTOR © VICTOR KRAFT by Michael Barrett uch of my professional life has been spent on convincing music lovers Mthat categorizing music as “classical” or “popular” is a fool’s errand. I’m not surprised that people s t i l l c l i n g t o t h e s e d i v i s i o n s . S o m e w h o love classical masterpieces may need to feel reassured by their sophistication, looking down on popular culture as dis- posable and inferior. Meanwhile, pop music fans can dismiss classical music lovers as elitist snobs, out of touch with reality and hopelessly “square.” Fortunately, music isn’t so black and white, and such classifications, especially of new music, are becoming ever more anachronistic. With the benefit of time, much of our country’s greatest music, once thought to be merely “popular,” is now taking its rightful place in the category of “American Classics.” I was educated in an environment that was dismissive of much of our great American music. Wanting to be regarded as a “serious” musician, I found myself going along with the thinking of the times, propagated by our most rigid conservatory student in the 1970’s, I grew work that studiously avoided melody or key academic composers and scholars of up convinced that Aaron Copland was a signature. the 1950’s -1970’s. These wise men (and “Pops” composer, useful for light story This was the environment in American yes, they were all men) had constructed ballets, but not much else. -

Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill?

DAVID DREW Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill? The pretexts for the present paper are the author's essays >Der T#g der Ver heissung and the Prophecies of jeremiah<, Tempo, 206 (October 1998), 11- 20, and >Der T#g der Verheissung: Weill at the Crossroads<, 1impo, 208 (April 1999), 335-50. As suggested in the preface to the second essay, the paper is intended to function both as a free-standing entity and as an extended bridge between the last section of the earlier essay and the first section of its successor. According to Meyer Weisgal's detailed account of the origins of The Eter nal Road, Reinhardt had no inkling of his plans until their November 1933 meeting in Paris.1 Weisgal began by outlining the idea of a biblical drama that would for the first time evoke the Old Testan1ent in all its breadth rather than in isolated episodes. At the end of his account, according to Weisgal, Reinhardt sat motionless and in silence before saying »very sim ply<< »But who will be the author of this biblical play and who will write the mu sic?<< . »You are the master<< , I said, ••It is up to you to select them<<. Again there was a long uncomfortable pause and Reinhardt said that he would ask Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill to collaborate with him. With or without prior notice2, the problems inherent in Weisgal's com mission were so complex that Reinhardt would have had good reason for Meyer W. Weisgal, >Beginnings of The Eternal Road<, in: T"he Etemal Road (New York 1937 - programme-book for the production by MWW and Crosby Gaige at the Man hattan Opera House), pp. -

English Literature, History, Children's Books And

LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 DECEMBER 13 LONDON HISTORY, CHILDREN’S CHILDREN’S HISTORY, ENGLISH LITERATURE, ENGLISH LITERATURE, BOOKS AND BOOKS ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS 13 DECEMBER 2016 L16408 ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS FRONT COVER LOT 67 (DETAIL) BACK COVER LOT 317 THIS PAGE LOT 30 (DETAIL) ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS AUCTION IN LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 SALE L16408 SESSION ONE: 10 AM SESSION TWO: 2.30 PM EXHIBITION Friday 9 December 9 am-4.30 pm Saturday 10 December 12 noon-5 pm Sunday 11 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 12 December 9 am-7 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 101 (DETAIL) SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR L16408 “BABBITTY” Lukas Baumann [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 +44 (0)20 7293 5283 fax +44 (0)20 7293 5904 fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 [email protected] POST SALE SERVICES Kristy Robinson Telephone bid requests should Post Sale Manager Peter Selley Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR PAYMENT, DELIVERY Specialist Specialist to the sale. This service is AND COLLECTION +44 (0)20 7293 5295 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 offered for lots with a low estimate +44 (0)20 7293 5220 [email protected] [email protected] of £2,000 and above. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

AURUS — Classic Analogue Feel with the Power of a Digital Console!

22 directly accessible parameters — 11 dual concentric encoders per channel strip • ready for 96 kHz • parallel mixdown to multiple multichannel formats • fully integrated into the NEXUS STAR routing system AURUS — Classic analogue feel with the power of a digital console! AURUS the Direct-Access Console The novel digital mixing-console architecture introduced by the The unusually large number of controls (at least for a digital young and innovative Stage Tec team in 1994 has since signifi cantly con sole) provide instant access to the desired audio channels. infl uenced the design of current digital desks and not only in ap pear- De pending on the confi guration, up to 96 channel strips and 300 ance. And CANTUS — their fi rst digital console — became a huge au dio channels are available. Optimum access to all controls and success. per fect legibility of all displays and indicators offers a high degree In 2002, Stage Tec introduced a new fi rst-class mixing console of user-friendliness whilst keeping the training period short. developed from scratch: AURUS — the Direct-Access Console. Many users have since evaluated the console, opted for it, and given AURUS as a desktop version or with easily removable legs is feedback and made suggestions for optimisations. Thus, the AURUS the perfect tour companion. Thanks to its compact size and low is now available incorporating generic software functions for broad- weight, AURUS guarantees ultra-short set-up times, saving time and cast ing, sound reinforcement, theatres, and recording. money. AURUS continues the original concept of consistent sep a ra tion These characteristics as well as the hot-swap capabilities of all of con sole and I/O matrix, which allows for setting up distributed hard ware elements, full redundancy up to double optical lines, low and effi cient audio networks; but at the same time, this sep a ra tion power consumption, and thus low heat dissipation make AURUS is supple mented by a unique control concept, instant access to all highly suitable for OB truck installation, as well. -

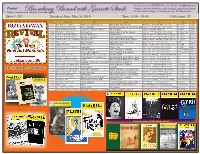

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack at Public Radio Exchange, > Exchange.Prx.Org > Broadway Bound *Playlist Is Listed by Show Title/Disc, Not in Order of Play

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast, heard free of charge Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack at Public Radio Exchange, > exchange.prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed by show title/disc, not in order of play. Show #: 287 Broadcast Date: May 26, 2018 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 27 Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 2:43 (m)F Lowe (l)A J Lerner Almost Like Being In Love Marion Bell, David Brooks Brigadoon - Original Broadway Cast 1947 RCA Victor 1947 3/13/1947 - 7/31/1948. 581 perf. One 1947 Tony Award: Best Choreography, Agnes CDS Brig 0:09 7 1988 5/6/06 11/25/064/12/08 3/13/10 5/26/18 De Mille 4:13 [m]John Kander [l]FRed Ebb Don't Tell Mama Natasha Richardson & the Kit Kat Girls Cabaret: The New Broadway Cast Recording RCA Victor 1998 3/19/1998 - 1/4/2004. 2377 perf. Four 1998 Tony Awards: Best Revival; Best Actor CDS 3 20 1998 12/8/07 2/18/12 1/3/15 5/26/18 - Alan Cumming; Best Actress - Natasha Richardson; Best Featured Actor - Ron Rifkin. 3:07 (m)Fred Lowe(l)Alan Lerner I Loved You Once in Silence Juliewith AlanAndrews Cumming Camelot Original Broadway Cast Columbia 1960 12/3/1960 - 1/5/1963. 873 perf. 4 Tony Awards CDS Cam 16 1998 12/9/06 12/8/07 7/25/09 2/13/10 11/22/142/14/15 5/26/18 8:22 R Rodgers/ O Hammerstein If I Loved You Sally Murphy & Michael Hayden Carousel - 1994 Broadway Cast recording Broadway Angel 1994 3/24/1994 - 1/15/1995. -

Die Dreigroschenoper Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Hauptmann (1897-1973), Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956)

1/14 Data Livret de : Elisabeth Die Dreigroschenoper Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Hauptmann (1897-1973), Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) Langue : Allemand Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres musicales Date : 1928 Note : Pièce avec musique en 3 actes. - Livret de Bertolt Brecht et Elisabeth Hauptmann, d'après "The beggar's opera" de John Gay. - 1re exécution : Berlin, Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, le 31 août 1928, avec Lotte Lenya (soprano) Le compositeur en a tiré une suite pour instruments à vent intitulée "Kleine Dreigroschenmusik" Domaines : Musique Autres formes du titre : L'opéra de quat'sous (français) The threepenny opera (anglais) Détails du contenu (4 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Contient (2) Die Dreigroschenoper. 1. , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Die Dreigroschenoper. Die , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Aufzug. Barbara Song Moritat von Mackie Messer (1928) (1928) Voir aussi (1) Die Dreigroschenoper : film , Georg Wilhelm Pabst (1931) (1885-1967) data.bnf.fr 2/14 Data Voir l'œuvre musicale (1) Kleine Dreigroschenmusik , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) (1928) Éditions de Die Dreigroschenoper (175 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Enregistrements (136) DIE DREIGROSCHENOPER = , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), extrait : DE L'OPERA DE , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), L'Opéra de Quat' sous S.l. : s.n. , s.d. QUAT'SOUS A SEPTEMBER S.l. : s.n. , s.d. SONG extrait : GUITARE PARTY , C. Gray, D. Bennett, Ted choix : Chanson pour le , Mertens, J. Paris, J. Snyder [et autre(s)], S.l. : théâtre Sundstrom [et autre(s)], S.l. s.n. , s.d. : s.n. , s.d. extrait : LES GRANDES , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), extrait : JULIETTE GRECO : , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), CHANSONS DE JULIETTE Hubert Giraud (1920-2016), JE SUIS COMME JE SUIS Stéphane Golmann GRECO René-Louis Lafforgue (1921-1987), Jacques (1928-1967) [et autre(s)], Prévert (1900-1977) [et S.l. -

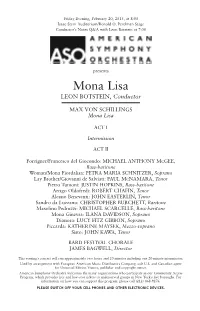

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Topical Weill: News and Events

Volume 27 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 2009 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events Summertime Treats Londoners will have the rare opportunity to see and hear three Weill stage works within a two-week period in June. The festivities start off at the Barbican on 13 June, when Die Dreigroschenoper will be per- formed in concert by Klangforum Wien with HK Gruber conducting. The starry cast includes Ian Bostridge (Macheath), Dorothea Röschmann (Polly), and Angelika Kirchschlager (Jenny). On 14 June, the Lost Musicals Trust begins a six-performance run of Johnny Johnson at Sadler’s Wells; Ian Marshall Fisher directs, Chris Walker conducts, with Max Gold as Johnny. And the Southbank Centre pre- sents Lost in the Stars on 23 and 24 June with the BBC Concert Orchestra. Charles Hazlewood conducts and Jude Kelly directs. It won’t be necessary to travel to London for Klangforum Wien’s Dreigroschenoper: other European performances are scheduled in Hamburg (Laeiszhalle, 11 June), Paris (Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 14 June), and back in the Klangforum’s hometown, Vienna (Konzerthaus, 16 June). Another performing group traveling to for- eign parts is the Berliner Ensemble, which brings its Robert Wilson production of Die Dreigroschenoper to the Bergen Festival in Norway (30 May and 1 June). And New Yorkers will have their own rare opportunity when the York Theater’s “Musicals in Mufti” presents Knickerbocker Holiday (26–28 June). Notable summer performances of Die sieben Todsünden will take place at Cincinnati May Festival, with James Conlon, conductor, and Patti LuPone, Anna I (22 May); at the Arts Festival of Northern Norway, Harstad, with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra led by HK Gruber and Ute Gfrerer as Anna I (20 June); and in Metz, with the Orchestre National de Lorraine, Jacques Mercier, conductor, and Helen Schneider, Anna I (26 June). -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

WWD-Mainrelease 9-07

For 200 million years the Dinosaurs ruled the earth Now, they’re back to roam the arenas of America in an extraordinary new theatrical production WALKING WITH DINOSAURS The Live Experience Based on the award-winning BBC Television Series WALKING WITH DINOSAURS – The Live Experience comes to North America on a two-year tour September 30, 2007 --- Dinosaurs return to the earth in a live theatrical arena show, WALKING WITH DINOSAURS – The Live Experience , based on the award-winning BBC Television Series. After playing for ten sold-out weeks in five cities in Australia, WALKING WITH DINOSAURS – The Live Experience is now on tour in North America for two years. 350,000 Americans have already seen the production since it opened in July 2007. WALKING WITH DINOSAURS – The Live Experience is brought to North America by Immersion Edutainment , headed by Bruce Mactaggart. Mactaggart said, “The BBC Series was a brilliant blend of special effects, escapism, excitement and information. Our show has that -- and it’s live. In this show, fifteen roaring, snarling “live” dinosaurs mesmerize the audience – and are as awe-inspiring as when they first walked on earth.” Mactaggart continued, “This is a show that could only fit in arenas – as the creatures are so absolutely immense in size. Audiences seated in the lower seats are all but overwhelmed by the dinosaurs, while those seated in higher seats can view the entire spectacle and panorama of the production. It is the closest you’ll ever get to experiencing what it was like when they walked and ruled the earth.” For more information, please visit www.dinosaurlive.com .