USHMM Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyrical Ballads

LYRICAL BALLADS Also available from Routledge: A SHORT HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE Second Edition Harry Blamires ELEVEN BRITISH POETS* An Anthology Edited by Michael Schmidt WILLIAM WORDSWORTH Selected Poetry and Prose Edited by Jennifer Breen SHELLEY Selected Poetry and Prose Edited by Alasdair Macrae * Not available from Routledge in the USA Lyrical Ballads WORDSWORTH AND COLERIDGE The text of the 1798 edition with the additional 1800 poems and the Prefaces edited with introduction, notes and appendices by R.L.BRETT and A.R.JONES LONDON and NEW YORK First published as a University Paperback 1968 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Second edition published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Introduction and Notes © 1963, 1991 R.L.Brett and A.R.Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Wordsworth, William 1770–1850 Lyrical ballads: the text of the 1978 edition with the additional 1800 poems and the prefaces. -

Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 5 2007 "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Margery Palmer McCulloch University of Glasgow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McCulloch, Margery Palmer (2007) ""A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 44–56. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margery Palmer McCulloch "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Edwin Muir's characterization in Scott and Scotland (1936) of "a very cu rious emptiness .... behind the wealth of his [Scott's] imagination'" and his re lated discussion of what he perceived as the post-Reformation and post-Union split between thought and feeling in Scottish writing have become fixed points in Scottish criticism despite attempts to dislodge them by those convinced of Muir's wrong-headedness.2 In this essay I want to take up more generally the question of twentieth-century interwar views of Walter Scott through a repre sentative selection of writers of the period, including Muir, and to suggest pos sible reasons for what was often a negative and almost always a perplexed re sponse to one of the giants of past Scottish literature. -

The Ancient Mariner and Parody

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons English: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 8-1999 ‘Supernatural, or at Least Romantic': the Ancient Mariner and Parody Steven Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/english_facpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Steven E. Jones, “‘Supernatural, or at Least Romantic': the Ancient Mariner and Parody," Romanticism on the Net, 15 (August 1999). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Michael Eberle-Sinatra 1996-2006. 'Supernatural, or at Least Romantic': the Ancient Mariner and Parody | Érudit | Romanticism on the Net n15 1999 | 'Supernatural, or at Least Romantic': the Ancient Mariner and Parody [*] Steven E. Jones Loyola University Chicago 1 An ancient literary practice often aligned with satire, parody "comes of age as a major comic expression during the Romantic period," as Marilyn Gaull has observed, the same era that celebrated and became known for the literary virtues of sincerity, authenticity, and originality. [1] Significant recent anthologies of Romantic-period parodies make the sheer bulk and topical range of such imitative works available for readers and critics for the first time, providing ample evidence for the prominence of the form. [2] The weight of evidence in these collections should also put to rest the widespread assumption that parody is inevitably "comic" or gentler than satire, that it is essentially in good fun. -

(Surname in Parentheses) = Bride's Maiden Name * = Colored LI = Date

LAST FIRST Current AGE POB LAST FIRST Current AGE POB Date of NAME NAME Residence NAME NAME Residence Marriage BRIDE BRIDE GROOM GROOM Aaron Mildred Irvington, NJ 26 PA Calabrese Edward Newark, NJ 25 NJ 20 May 1940 Elizabeth Abel Catherine Triangle, VA 18 VA Allen James Triangle, VA 23 VA 16 Dec 1939 Virginia Monroe Abel Dorothy Quantico, VA 18 VA Gass Edward Quantico, VA 28 MA 2 Sep 1939 Louise Abrams Miriam Ventnor City, 21 NJ Fertick Albert Philadelphia, 22 PA 29 Jul 1940 Frances NJ Abraham PA Abramson Sylvia Flushing, LI, 34 NY Tush Joseph Flushing, LI, 32 NY 23 Feb 1940 NY Sanford NY Accardi Anna Queens Village, 26 NY DiMaria Frank Brooklyn, NY 36 ITA 10 Oct 1940 (Aloi) NY Acha Myrtle Pontiac, MI 24 MI Ferguson John Nesbit Detroit, MI 35 PA 8 Apr 1939 Violet Rita Achter Sylvia Philadelphia, 21 NY Cohen Albert Philadelphia, 24 PA 29 Jul 1940 Beatrice PA PA Acker Edna Mae Philadelphia, 22 PA Tranausky Edward Philadelphia, 23 PA 11 May 1940 PA Martin PA Ackoff Anne Nancy Philadelphia, 22 PA Wallen Albert David Philadelphia, 35 PA 30 Jul 1940 PA PA Acty Sarah Washington, 21 VA Jones Bernard Glendale, MD 23 MD *5 Jul 1940 Elizabeth DC Summerfield POB = Place of Birth (Surname in parentheses) = Bride’s Maiden Name * = Colored LI = Date License Issued LAST FIRST Current AGE POB LAST FIRST Current AGE POB Date of NAME NAME Residence NAME NAME Residence Marriage BRIDE BRIDE GROOM GROOM Adair Mildred Jacksonville, 24 LA Hanlon Jack Harrisville, PA 24 PA 6 Jul 1939 FL Adair Margaret Washington, 42 DC Lane Franklin Washington, 44 CA 14 Oct 1939 -

I the DECADENT VAMPIRE by JUSTINE J. SPATOLA a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, the State University of N

THE DECADENT VAMPIRE by JUSTINE J. SPATOLA A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in English written under the direction of Dr. Ellen Malenas Ledoux and approved by ___________________________________ Dr. Ellen Malenas Ledoux ___________________________________ Dr. Timothy Martin ___________________________________ Dr. Carol Singley Camden, New Jersey October 2012 i ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Decadent Vampire By JUSTINE J. SPATOLA Thesis Director: Dr. Ellen Malenas Ledoux John William Polidori published "The Vampyre" in 1819, and, as the first person to author a work of English vampire fiction, he ultimately established the modern image of the aristocratic vampire, which writers such as Bram Stoker later borrowed. The literary vampire, exemplified by Lord Ruthven, reveals the influence of Burkean aesthetics; however, the vampire's portrayal as a degenerate nobleman and his immense popularity with readers also ensured that he would have a tremendous impact on nineteenth century culture. "The Vampyre" foreshadows the more socially-aware Gothic literature of the Victorian period, but the story's glorification of the perverse vampire also presents a challenge to traditional morality. This essay explores the influence of the literary vampire not just on broader aspects of nineteenth century culture but also its influence on the Decadent Movement (focusing on the works of writers such as Charles Baudelaire, Théophile Gautier, and Oscar Wilde) in order to show how it reflects the decadent abnormal. In doing so, however, this essay also questions whether decadence ought to be understood as a nineteenth century European phenomenon, as opposed to a ii movement that was confined to the late Victorian period; the beliefs shared by decadent writers often originated in Romanticism, and the Romantics' fascination with the supernatural suggests that they were perhaps as interested in perverse themes as the Decadents. -

Whose Greatness Is So Beyond Dispute That We Would Rather Listen to Some- Thing Else"

whose greatness is so beyond dispute that we would rather listen to some- thing else". For I have witnessed electrifying performances (too few, alas) which gripped also the man in the street In fact, the last apotheosis is among the most sublime finales in all opera; it transcends Schiller's slightly perfunctory ending, just as Bizet's final duet in 'Carmen' (accord- ing to Busoni, "one of the supreme achievements in music") dwarfs Merimde's effective but hasty climax in the sombre forest. What does it matter if the setting happens to be less plausible, so long as the artist's genius is incomparably more dramatic and compelling ? That, too, is why I prefer Rossini's 'Tell', despite its dull patches, to the no doubt very exhilarating buffooneries of his most popular works. Besides, Rossini himself felt this very keenly; he explained his enigmatic silence after Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ml/article/LII/2/192/1122293 by guest on 27 September 2021 'Tell' by remarking sardonically: "Why should I go on chasing hares after I have killed the elephant?" Finally, instead of the usually rather unprepossessing picture of Rossini, which transforms him either into an inept caricature of the grossly corpulent Prince Regent, or else makes him pose self-consciously as the immortal creator of 'Tell', we have an original and attractive frontispiece: the title-page of an early edition of 'La Vie de Rossini par M. De Stendhal', signed, however, by M. H. Beyle. We can imagine the first great psycho-analytical novelist of the nineteenth century, with a sigh of heart-felt relief, shrugging his broad shoulders and, for a moment, allowing his shrewd gaze to rest, a trifle wistfully, upon the preliminary sketches of a work which meant infinitely more to him: his forthcoming masterpiece, 'Le Rouge et le Noir'. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Kathleen Lenore Komar

CURRICULUM VITAE Kathleen Lenore Komar: Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature & German, UCLA, 2014 Member of the Executive Board of the International Comparative Literature Association 2010- President of the American Comparative Literature Association March 2005-2007 Chair of the Academic Senate of UCLA 2004-05 Vice-Chair of the Academic Senate, UCLA 2003-04 Vice-President of the American Comparative Literature Association, 2003-2005 Associate Dean of the Graduate Division, UCLA 1992-2002 Director of the Humanities Cluster Program, UCLA 1991-92 Chair of the Program in Comparative Literature UCLA 1986-89 Full Professor Step VI, Department of Comparative Literature UCLA 2003 Full Professor, Department of Germanic Languages & Program in Comparative Literature UCLA 1990- Associate Professor, Department of Germanic Languages & Program in Comparative Literature UCLA l984-1990 Assistant Professor, Department of Germanic Languages & Program in Comparative Literature UCLA l977-84 EDUCATION: 1977 Ph.D. in Comparative Literature (Major literature German, minors in English and French), PRINCETON UNIVERSITY 1975 M.A. in Comparative Literature (Major in German, minors in English and French), PRINCETON UNIVERSITY 1971-72 Study abroad at the Universities of Bonn and Freiburg. 1971 B.A. in English, Honors in the College, Special Honors in English, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO HONORS & RECOGNITIONS: 2014 Promoted to Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature & German, UCLA 2014 Awarded the University of California systemwide Oliver Johnson -

The Death of Beauty in Edgar Allan Poe's Poetry

The Death of Beauty in Edgar Allan Poe's Poetry Assistant Instructor Maha Qahtan University of Baghdad/ College of Education for Women Department of English Language Abstract In "The Philosophy of Composition" Poe writes that the death of a beautiful woman is the most poetical subject in the world. This perverse and personal opinion is the outcome of tragedies in his life. Poe was deeply attached to various beautiful women who died young, leaving him obsessed with his need of woman and fear of death and annihilation. The study traces the nature of Poe's relation with woman and his notion of her death as reflected in his aesthetic theory and poetry. The poems chosen in this study are notable for their tone of sorrow after the death of a beautiful beloved which becomes a predominant motif in Poe's literary output. "رحيل الجمال في شعر ادكر الن بو" في مقالته المشهورة "فلسفة الكتابةة" يةى اكرةى الةو بةو ات مةوأ امةىلة يمتلةة يضتعةى مو ةو ا شضىياً ثىاً، و ربما يكوت هذا الىلي الغىيب نو ا ما انضكاس لمحطاأ مأساويه في حتاة الشةا ى نفسةه ففي حتاة "بةو" نسةا يمةتتأ مةتو معكةىا ً, تاررةاأ "بةو"مهوسةاً بحايتةه للمةىلو ومسةكوناً ب ةو مةو الفنةا وتتمتز القصةةا ا الم تةةارة فةةي هةةذو الاراسةةة بنعىتهةا الحزينةةه بضةةا رحتةة، الحعتعةةة ال متلةةة، والةةذي اصعح مو و ة ر تسة في المن ز الشضىي "لعو" 2 Thou wast that all to me, love, For which my soul did pine- A green isle in the sea, love, A fountain and a shrine, And wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers, And all the flowers were mine . -

The Influence of the German Literary Vampire on Constructions of Race and Nation in Nineteenth Century British Vampire Fiction

“IN OUR VEINS FLOWS THE BLOOD OF MANY BRAVE RACES”: THE INFLUENCE OF THE GERMAN LITERARY VAMPIRE ON CONSTRUCTIONS OF RACE AND NATION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH VAMPIRE FICTION By Amanda L. Alexander A Project Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature Committee Membership Dr. Mary Ann Creadon, Committee Chair Dr. Janet Winston, Second Reader Dr. Nikola Hobbel, Graduate Coordinator December 2013 ABSTRACT “IN OUR VEINS FLOWS THE BLOOD OF MANY BRAVE RACES”: THE INFLUENCE OF THE GERMAN LITERARY VAMPIRE ON CONSTRUCTIONS OF RACE AND NATION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY BRITISH VAMPIRE FICTION Amanda L. Alexander The literary vampire figure, as it would be recognized today, entered English literature through translations of late eighteenth century German poetry. The purpose of this project is to explore how the relationship between German vampire ballads and British vampire narratives acts as a literary manifestation of German-British cultural and political attitudes and interactions in the roughly century and a half before World War I. This relationship will be discussed through an exploration of the constructs of blood and body within vampire narratives in direct relationship to sociocultural discourses of race in Pre-WWI England. This project seeks to explore the following questions: Are vampire narratives a fictional response to “the German Problem” of nineteenth century imperialism? What is the significance of the vampire figure being outside normative constructions of race and nation? Drawing on Goethe’s “Bride of Corinth” and Bürger’s “Lenore,” I will do a close reading of John Polidori’s The Vampyre, J.S. -

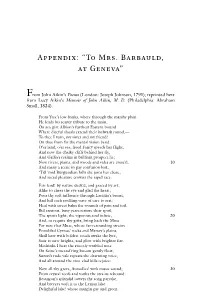

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva”

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva” From John Aikin’s Poems (London: Joseph Johnson, 1791); reprinted here from Lucy Aikin’s Memoir of John Aikin, M. D. (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1824). From Yare’s low banks, where through the marshy plain He leads his scanty tribute to the main, On sea-girt Albion’s furthest Eastern bound Where direful shoals extend their bulwark round,— To thee I turn, my sister and my friend! On thee from far the mental vision bend. O’er land, o’er sea, freed Fancy speeds her flight, And now the chalky cliffs behind her fly, And Gallia’s realms in brilliant prospect lie; Now rivers, plains, and woods and vales are cross’d, 10 And many a scene in gay confusion lost, ’Till ’mid Burgundian hills she joins her chase, And social pleasure crowns the rapid race. Fair land! by nature deck’d, and graced by art, Alike to cheer the eye and glad the heart, Pour thy soft influence through Laetitia’s breast, And lull each swelling wave of care to rest; Heal with sweet balm the wounds of pain and toil, Bid anxious, busy years restore their spoil; The spirits light, the vigorous soul infuse, 20 And, to requite thy gifts, bring back the Muse. For sure that Muse, whose far-resounding strains Ennobled Cyrnus’ rocks and Mersey’s plains, Shall here with boldest touch awake the lyre, Soar to new heights, and glow with brighter fire. Methinks I hear the sweetly-warbled note On Seine’s meand’ring bosom gently float; Suzon’s rude vale repeats the charming voice, And all around the vine-clad hills rejoice: Now all thy grots, Auxcelles! with music sound; 30 From crystal roofs and vaults the strains rebound: Besançon’s splendid towers the song partake, And breezes waft it to the Leman lake. -

Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, Including Letters and Notices of Her Family And

_ 4 ! I I S I j ffipni ^mmmumfrfomro pwiiwt f^u^ \ tjjtfJWtft, ny* o . FROM THE LIBRARY OF REV. LOUIS FITZGERALD BENSON, D. D. BEQUEATHED BY HIM TO THE LIBRARY OF PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ZMfbkai DKXiom Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/mrsbarbaOOIebr . from- czs ^A£&c&zllu?7Z' dyJI^ec^^vooa^ : M E M O I JJ OF MKS. BAEBAULD, INCLUDING LETTERS AND NOTICES OF HER FAMILY AND FRIENDS. BY HER GREAT NIECE ANNA LETITIA LE BRETON. LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1874. [ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.] PREFACE. The writer of the following Memoir is one of the few surviving members of Mrs. Barbauld's family who retains a personal recollection of her, having spent much of her early life under her care, owing her like- wise a large debt of gratitude and love. Earnestly desiring to revive some memory of one who though enjoying in her lifetime a considerable amount of literary fame, is now, from the circumstance of her works having been long out of print and difficult to procure, comparatively unknown to the present generation, the author has availed herself of a collection of letters and family papers in her possession, to compile a fuller account of the life and family of Mrs. Barbauld, than her niece Lucy Aikin thought herself justified in doing, when she wrote the original Life, prefixed to the edition of the Works of Mrs. Barbauld, published soon after her death in 1825. Feelings of delicacy towards members of Mr. Barbauld's family, then living, prevented the true ac- count being given of the unfortunate state of miud with which her husband became afflicted, a calamity which in a great degree crippled her powers for many of the 11 best years of her life. -

©2008 Kathryn Lenore Steele ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2008 Kathryn Lenore Steele ALL RIGHTS RESERVED NAVIGATING INTERPRETIVE AUTHORITIES: WOMEN READERS AND READING MODELS IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY by KATHRYN LENORE STEELE A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Literatures in English written under the direction of Paula J. McDowell and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Navigating Interpretive Authorities: Women Readers and Reading Models in the Eighteenth Century By KATHRYN LENORE STEELE Dissertation Director: Paula J. McDowell Challenging existing notions of the oppositional reader, this dissertation proposes the model of limited interpretive authority as a new way of understanding reading practices in eighteenth-century England. It examines the women readers of Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa as illustrations of this concept. Chapter 1, a literature review, suggests that even as methodologies become more flexible, the modern, individual, and secular reader continues to inform studies of historical reading. Arguing that the field requires a reading model describing more limited individual interpretive authority, this chapter turns to eighteenth-century instructions for reading the Bible. These texts employ a language of self-discipline and self-censorship that characterizes reading