Fall 2016 – Spring 2017) • a Refereed Journal • ISSN 1545-2271 • ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 22, 1947 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep October 1947 10-22-1947 Daily Eastern News: October 22, 1947 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1947_oct Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: October 22, 1947" (1947). October. 4. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1947_oct/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 1947 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in October by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern State ·News • isor, left "Tell the Truth and Don't Be Afraid" 1y trip to VOL. XXXIII NO. 5 EASTERN ILLINOIS STATE COLLEGE ... CHARLESTON �ED., OCT. 22, 1947 .e of those :RN'S 83RD HomecomiQog 'fifoua time in histol-y of the t�e • ge. ast sutnme,r the nQ.me of the coHege'1fflll 'th..plans for wider Homecoming Festivities Begin Tomorrow turns . Olsen's Music for Arlene Swearingen Saturday Dance - Al,umni to Meet To Reign _as Queen GEORGE OLSEN and his "Music After'lun cheon ARLENE SWEARINGEN w i I I �s been of Tomorrow" will be the feature reign as queen over 1947 Home attraction of Eastern's Homecom Tenn. EASTERN'S ALUMNI associa- coming, Her attendants are June ing dance at 8:00 ·p. m. on Satur tion will hold an election of of Bubeck, senior; Harriett Smith, day, October 25, 1947. The Wo ficers at its business meeting, fol junior; Betty Kirkham, s'bpho men's gym will be decorated in lowing the Alumni luncheon in the more; and Alice Hanks, freshman. -

Only Believe Song Book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, Write To

SONGS OF WORSHIP Sung by William Marrion Branham Only Believe SONGS SUNG BY WILLIAM MARRION BRANHAM Songs of Worship Most of the songs contained in this book were sung by Brother Branham as he taught us to worship the Lord Jesus in Spirit and Truth. This book is distributed free of charge by the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, with the prayer that it will help us to worship and praise the Lord Jesus Christ. To order the Only Believe song book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, write to: Spoken Word Publications P.O. Box 888 Jeffersonville, Indiana, U..S.A. 47130 Special Notice This electronic duplication of the Song Book has been put together by the Grand Rapids Tabernacle for the benefit of brothers and sisters around the world who want to replace a worn song book or simply desire to have extra copies. FOREWARD The first place, if you want Scripture, the people are supposed to come to the house of God for one purpose, that is, to worship, to sing songs, and to worship God. That’s the way God expects it. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS, January 3, 1954, paragraph 111. There’s something about those old-fashioned songs, the old-time hymns. I’d rather have them than all these new worldly songs put in, that is in Christian churches. HEBREWS, CHAPTER SIX, September 8, 1957, paragraph 449. I tell you, I really like singing. DOOR TO THE HEART, November 25, 1959. Oh, my! Don’t you feel good? Think, friends, this is Pentecost, worship. This is Pentecost. Let’s clap our hands and sing it. -

Jesus Walks on Water MATTHEW 14:25–34

GOSPEL STORY CURRICULUM (NT) ● PRESCHOOL LESSON 22 Jesus Walks on Water MATTHEW 14:25–34 BIBLE TRUTH JESUS IS THE SON OF GOD WHO SAVES ● PRESCHOOL LESSON 22 LESSON 22 LESSON SNAPSHOT 1. OPENING ACTIVITY AND INTRODUCTION ................... 5 MIN SUPPLIES: basin of water; various small objects to test to see whether they float or sink Jesus Walks on Water 10 MIN 2. BIBLE STORY MATTHEW 14:25–34 ........................................... SUPPLIES: The Gospel Story Bible (story 100) 3. BIBLE STORY DISCUSSION ................................ 5 MIN Where Is the Gospel? SUPPLIES: Bible (ESV preferred); Review “Where Is the Gospel?” to prepare 4. SNACK QUESTIONS .....................................10 MIN SUPPLIES: snack food and beverage 5. SWORD BIBLE MEMORY ................................ 5–10 MIN 6. ACTIVITIES AND OBJECT LESSONS (CHOOSE ONE OR MORE) .... 20–30 MIN Coloring Activity SUPPLIES: coloring page for NT Lesson 22—one for each child; markers or crayons Walking on Water SUPPLIES: large washbasin filled with water; a large towel All Who Touched Him Were Healed SUPPLIES: large robe or sheet to serve as a cloak 7. CLOSING PRAYER ....................................... 5 MIN TOTAL 60–75 MIN PAGE 161 • WWW.GOSPELSTORYFORKIDS.COM ● PRESCHOOL LESSON 22 THE LESSON OPENING ACTIVITY AND INTRODUCTION .................5 MIN In today’s lesson the children will learn the story of when Jesus walked on water. Bring a small basin of water to class, along with some small random objects to see whether they sink or float. Hold up the objects one by one and ask the children if they will float. Then place them, one at a time, in the water for the class to see. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Psalm 100 Sermon: Beginning with Moses and All the Prophets Reading

Call to worship – Psalm 100 Sermon: Beginning with Moses and all the Prophets Reading: Luke 24: 13- 35 Jesus seeking you. Jesus walking beside you. Jesus revealing Himself to you. Your response. Please hold these four thoughts in your mind as we meet this morning. My heart leapt when I saw that the lectionary reading for this morning was the passage where Luke describes the two on the road to Emmaus. It is a passage that has been important to me and one that is rich in teaching. Many of you will be familiar with the passage, but I want us to look at what is described. It is the morning of the resurrection when the woman who had taken spices they had prepared went to the tomb which they found to be empty. Two men appeared to the woman and say, “He is not here; He has risen!” The women are reminded that Jesus had said that he would be delivered into the hands of sinful men, be crucified, but on the third day would be raised again. And we read then that the women told these things to the Eleven and to all the others. After this, Cleopas and another left and were walking to the village called Emmaus. This was about 11 km from Jerusalem. We read that they were talking about everything that had happened when Jesus himself came up and walked with them. We read that they were kept from recognising him. Jesus then asks them, “What are you discussing together as you walk along?” They actually stop walking and Cleopas asks, “Are you only a visitor to Jerusalem and do not know the things that have happened there in these days?” Jesus answers, “What things?”. -

Think Before You Ink Disturbing and Morbid and Is Con

·Entertainment Here Comes Treble OFWGKTA! By Ian Chandler _By Meg Bell By.Brent Bosworth heme: Ho Ho Hardcore Dean Martin - "Walking In a Win Theme: Yuletide cheer "Christmas Eve Sarjevo".- Trans Odd Future .was formed ant to cause your chuckle to re ter Wonderland" The day after Thanksgiving, IT be ·Siberian Orchestra by Tyler, the Creator, and they re emble \l spherical container filled You kids need a shot of old school gins. That is the constant streain .of Ol!e. of the mo!!t popular ~ode lea8ed their first album in 2008. The o the brim with a general gelatin . espresso in your puny little modem Christmas music on all radios: It Christmas songs, you can't have . members that form the group are ubstance? Listen hither, and may lattes. Taste this jazzy version of a seems like you can't escape jt. So Chri'stmas p laylist without this Tyler, the Creator; Earl Sweatshirt; our spirits be roused with the warm winter wonderland, sung by the instead, plug in your headphones "Thank God It's Christmas" Hodgy Beat;, Domo Genesis; Frank trelight of the seasoij. Dino lllmself. May it digest well with and give this mix a try. It's slire to Queen · · Ocean; Mike G; Left Brain; Taco ugust Burns Red"."" "Carol of the you and yours. Fun fact: "The King spread some holiday cheer. Any playlist with Queen is a win Bennett; Jasper Dolphin; Syd tha ells" of Cool" was born in Steubenville, "Baby It's Cold Outside" -Anthony ner, and this adds a bit of gl~m . -

Listening to Compton's Hip-Hop Landscape" (2016)

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 4-29-2016 "Yo, Dre, I've Got Something To Say": Listening to Compton's Hip- Hop Landscape Ian T. Spangler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Spangler, Ian T., ""Yo, Dre, I've Got Something To Say": Listening to Compton's Hip-Hop Landscape" (2016). Student Research Submissions. 55. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/55 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "YO, DRE, I'VE GOT SOMETHING TO SAY": LISTENING TO COMPTON'S HIP-HOP LANDSCAPE An honors paper submitted to the Department of Geography of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Ian T Spangler April 2016 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Ian T. Spangler 04/29/16 (digital signature) o'Yo, Dre,I've Got Something to Say:" Listening to Compton's Hip-Hop Landscape By Ian Spangler A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in Geography Department of Geography University of Mary Washington Fredericksburg, VA 2240I April29,2016 Stephen P. -

2015 Year in Review

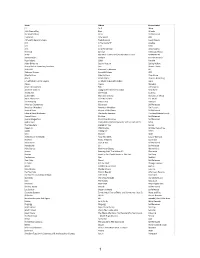

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC a Study on Collective Identity and Social Movements

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC A study on collective identity and social movements Dzeneta Sadikovic Department of Global and Political Studies Human Rights III (MR106S) Bachelor thesis, 15hp 15 ETC, Fall/2019 Supervisor: Dimosthenis Chatzoglakis Abstract This study is an analysis of musical lyrics which express oppression and discrimination of the African American community and encourage potential action for individuals to make a claim on their rights. This analysis will be done methodologically as a content analysis. Song texts are examined in the context of oppression and discrimination and how they relate to social movements. This study will examine different social movements occurring during a timeline stretching from the era of slavery to present day, and how music gives frame to collective identities as well as potential action. The material consisting of song lyrics will be theoretically approached from different sociological and musicological perspectives. This study aims to examine what interpretative frame for social change is offered by music. Conclusively, this study will show that music functions as an informative tool which can spread awareness and encourage people to pressure authorities and make a claim on their Human Rights. Keywords: music, politics, human rights, freedom of speech, oppression, discrimination, racism, culture, protest, social movements, sociology, musicology, slavery, civil rights, African Americans, collective identity List of Contents 1. Introduction p.2 1.1 Topic p.2 1.2 Aim & Purpose p.2 1.3 Human Rights & Music p.3 1.4 Research Question(s) p.3 1.5 Research Area & Delimitations p.3 1.6 Chapter Outline p.5 2. Theory & Previous Research p.6 2.1 Music As A Tool p.6 2.2 Social Movements & Collective Behavior p.8 2.2.1 Civil Rights Movement p.10 3. -

Milwaukee Holiday Lights Festival

MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL — 20 SEASONS OF LIGHTS & SIGHTS — NOVEMBER 15, 2018 - JANUARY 1, 2019 DOWNTOWN MILWAUKEE • milwaukeeholidaylights.com IT’S THE MOST WONDERFUL TIME OF THE Y’EAR! MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL – MILWAUKEE HOLIDAY LIGHTS FESTIVAL 20 SEASONS OF LIGHTS & SIGHTS KICK-OFF EXTRAVAGANZA November 15, 2018 – January 1, 2019 Thu, November 15 | 6:30pm Nobody does the holidays quite like Milwaukee! In celebration of our 20th Pre-show entertainment beginning at 5:30pm season, we’re charging up the town to light millions of faces. From all-day Pere Marquette Park adventures to evening escapes, guests of all ages will delight in our merry In celebration of 20 seasons, we’re delivering measures. So hop to something extraordinary! a magical lineup full of holiday cheer. Catch performances by Platinum, Prismatic Flame, #MKEholidaylights Milwaukee Youth Symphony Orchestra, Jenny Thiel, Young Dance Academy, and cast members from Milwaukee Repertory Theater’s “A Christmas Carol” and Black Arts MKE’s “Black Nativity” presented by Bronzeville Arts Ensemble. Fireworks and a visit from Santa will top off the night. Plus, after the show, take in downtown’s newly lit scenes with free Jingle Bus rides presented by Meijer and powered by Coach USA. If you can’t make the party, tune into WISN 12 for a live broadcast from 6:30pm to 7pm. “WISN 12 Live: Holiday Lights Kick-Off” will be co-hosted by Adrienne Pedersen and Sheldon Dutes. 3RD 2ND SCHLITZ PARK TAKE IN THE SIGHTS ABOARD THE JINGLE BUS CHERRY presented by meijer LYON Thu – Sun, November 15 – December 30 | 6pm to 8:20pm VLIET WATER OGDEN PROSPECT AVENUE FRANKLIN Plankinton Clover Apartments – 161 W. -

The Impressions, Circa 1960: Clockwise from Top: Fred Cash, Richard Brooks> Curtis Mayfield, Arthur Brooks, and Sam (Pooden

The Impressions, circa 1960: Clockwise from top: Fred Cash, Richard Brooks> Curtis Mayfield, Arthur Brooks, and Sam (Pooden. Inset: Original lead singer Jerry Butler. PERFORMERS Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions BY J O E M cE W E N from the union of two friends, Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield of Chicago, Illinois. The two had sung together in church as adolescents, and had traveled with the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers and the Traveling Souls Spiritual Church. It was Butler who con vinced his friend Mayfield to leave his own struggling group, the Alfatones, and join him, Sam Gooden, and brothers Richard and Arthur Brooks— the remnants of another strug gling vocal group called the Roosters. According to legend, an impressive performance at Major Lance, Walter Jackson, and Jan Bradley; he also a Chicago fashion show brought the quintet to the at wrote music that seemed to speak for the entire civil tention of Falcon Records, and their debut single was rights movement. A succession of singles that began in recorded shortly thereafter. “For Your 1964 with “Keep On Pushing” and Precious Love” by “The Impressions SELECTED the moody masterpiece “People Get featuring Jerry Butler” (as the label DISCOGRAPHY Ready” stretched through such exu read) was dominated by Butler’s reso berant wellsprings of inspiration as nant baritone lead, while Mayfield’s For Your Precious Love.......................... Impressions “We’re A Winner” and Mayfield solo (July 1958, Falcon-Abner) fragile tenor wailed innocently in the recordings like “(Don’t Worry) If background. Several follow-ups He Will Break Your Heart......................Jerry Butler There’s A Hell Below We’re All Going (October 1960, Veejay) failed, Butler left to pursue a solo ca To Go” and “Move On Up,” placing reer, and the Impressions floundered. -

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER Along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, what type of music is played 1 Arts with the accordion? Zydeco 2 Arts Who wrote "Their Eyes Were Watching God" ? Zora Neale Hurston Which one of composer/pianist Anthony Davis' operas premiered in Philadelphia in 1985 and was performed by the X: The Life and Times of 3 Arts New York City Opera in 1986? Malcolm X Since 1987, who has held the position of director of jazz at 4 Arts Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City? Wynton Marsalis Of what profession were Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countee Cullen, major contributors to the Harlem 5 Arts Renaissance? Writers Who wrote Clotel , or The President’s Daughter , the first 6 Arts published novel by a Black American in 1833? William Wells Brown Who published The Escape , the first play written by a Black 7 Arts American? William Wells Brown 8 Arts What is the given name of blues great W.C. Handy? William Christopher Handy What aspiring fiction writer, journalist, and Hopkinsville native, served as editor of three African American weeklies: the Indianapolis Recorder , the Freeman , and the Indianapolis William Alexander 9 Arts Ledger ? Chambers 10 Arts Nat Love wrote what kind of stories? Westerns Cartoonist Morrie Turner created what world famous syndicated 11 Arts comic strip? Wee Pals Who was born in Florence, Alabama in 1873 and is called 12 Arts “Father of the Blues”? WC Handy Georgia Douglas Johnson was a poet during the Harlem Renaissance era.