NABMSA Newsletter Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

August 1935) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1935 Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935)." , (1935). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/836 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE AUGUST 1935 PAGE 441 Instrumental rr Ensemble Music easy QUARTETS !£=;= THE BRASS CHOIR A COLLECTION FOR BRASS INSTRUMENTS , saptc PUBLISHED FOR ar”!S.""c-.ss;v' mmizm HIM The well ^uiPJ^^at^Jrui^“P-a0[a^ L DAY IN VE JhEODORE pRESSER ^O. DIRECT-MAIL SERVICE ON EVERYTHING IN MUSIC PUBLICATIONS * A Editor JAMES FRANCIS COOKE THE ETUDE Associate Editor EDWARD ELLSWORTH HIPSHER Published Monthly By Music Magazine THEODORE PRESSER CO. 1712 Chestnut Street A monthly journal for teachers, students and all lovers OF music PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. VOL. LIIINo. 8 • AUGUST, 1935 The World of Music Interesting and Important Items Gleaned in a Constant Watch on Happenings and Activities Pertaining to Things Musical Everyw er THE “STABAT NINA HAGERUP GRIEG, widow of MATER” of Dr. -

Wilson's Series of Powerful Recurrent Stage Images Drawn From

to a degree. which Simoon is the last part. Based on a Thread of Winter If there is no story, then what’s the work short play by August Strindberg, Simoon Leslie Fagan; Lorin Shalanko about? Wilson’s series of powerful recurrent was never performed in a full version during Canadian Art Song Series stage images drawn from the famous physi- the composer’s lifetime. The subject matter, (canadianartsong.ca) cist Albert Einstein’s life serve as the work’s as gloomy as the uprooted Scot’s preferred L/R frame. The dramatic device is imaginatively music, is a tale of revenge and “murder by ! When reviewing underpinned by Glass’ composition for solo- suggestion,” as Chisholm has referred to it. (in early 2004) the ists, chorus and his instrumental ensemble. Polished orchestral characterizations, Bartók- first solo album by It’s further explored by the masterfully like cascading moods and an overlapping of Leslie Fagan, I stated conceived and movingly performed modern Western and Eastern musical idioms are just that “she is in a dance sequences choreographed by Childs. three reasons why this opera should have class of her own.” This new DVD release accurately reflects been recorded long ago. As it is, with the What a pleasure to the superb 2012 production I saw at Toronto’s help of the Erik Chisholm Trust, it is making conclude, some 12 Luminato that same year. Highlights of that its long overdue debut – and rightfully years later, that she performance included violin virtuoso Jennifer in Scotland! remains just as original. Her career has taken Koh made up to resemble Einstein – a life- Robert Tomas her to the world’s most important concert long amateur violinist – and the impres- stages, providing Fagan with opportunities to sively precise chorus masterfully conducted Derek Holman – A Play of Passion present both traditional (Handel, Mahler) and by the veteran Glass Ensemble member Colin Ainsworth; Stephen Ralls; Bruce contemporary (Poulenc, Kulesha) repertoire. -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

Rite of Spring

JUNE 6, 7, 8 classical series SEGERSTROM CENTER FOR THE ARTS Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall Concerts begin at 8 p.m. Preview talk hosted by Alan Chapman with Joseph Horowitz and Tony Palmer begins at 7 p.m. presents 2012-2013 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES CARL ST.CLAIR • conductor | JOSEPH HOROWITZ • artistic adviser SUSANA PORETSKY • soprano | HYE-YOUNG KIM • piano | TONY PALMER • film director TONG WANG • choreographer | MEMBERS OF UC IRVINE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) STRAVINSKY (1882 - 1971) Excerpts from The Nutcracker, Op. 71 Epilogue: Lullaby in the Land of Eternity No. 14, Pas de deux from The Fairy’s Kiss No. 12, Divertissement: Chocolate (Spanish Dance) INTERMISSION Aly Anderson, Melanie Anderson, Janelle Villanueva, Tivoli Evans, Ashley LaRosa, Skye Schmidt Excerpt from Stravinsky: Once at a Border (1982 film) Coffee (Arabian Dance) Directed by Tony Palmer Karen Wing, Ryan Thomas, Mason Trueblood Tea (Chinese Dance) STRAVINSKY Tracy Shen, Jeremy Zapanta The Rite of Spring Trepak (Russian Dance) PART I: Adoration of the Earth Alec Guthrie Introduction The Augurs of Spring—Dances of the Young Girls Excerpts from Swan Lake, Op. 20 Ritual of Abduction No. 1, Scene Spring Rounds No. 3, Dance of the Swans Ritual of the Rival Tribes Tiffany Arroyo, Tivoli Evans, Tracy Shen, Janelle Villanueva Procession of the Sage No. 5, Hungarian Dance (Czardas) The Sage Jennifer Lott, Karen Wing, Alec Guthrie, McCree O’Kelley Dance of the Earth No. 6, Spanish Dance PART II: The Sacrifice Celeste Lanuza, Jessica Ryan, Jeremy Zapanta Introduction Mystic Circle of the Young Girls Lullaby in a Storm from Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. -

20 - 23 June 2013 Lo N D O N W C 1 Main Sponsor Greetings DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

20 - 23 JUNE 2013 LO N D O N W C 1 Main Sponsor GREEtiNgs DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Sponsors & Cultural Partners Welcome This year we’re asking questions. The artist is the person in society focused day events. Many of Questions of filmmakers, who is being paid to stop and our films have panels or Q&As questions of artists and also try and deal with them, and to – check the website for details, questions of ourselves - all part create a climate in which more where you will also find our useful Faculty of Arts and Humanities UCL Faculty of Population Health Sciences Faculty of Medical Sciences Faculty of Brain Sciences of the third edition of Open people would have occasion to links – ‘if you liked this you might Faculty of The Built Environment Faculty of Engineering Sciences UCL Slade School of Fine Art Faculty of Social and Historical Sciences City Docs Fest. And we are stop. …You want to get people’s like that’ suggesting alternative celebrating the documentarian attention, stop them dead in their journeys through the festival. who changes things. Not only tracks. Get them to say, ‘oh wait a Media Partners changing their world, but minute!’ To turn the tables! To say, There is no single way of making changing our understanding of ‘everything I thought obtained, documentary – people can’t even the wider world. So, what is the doesn’t obtain: oh my God! What agree where documentary ends onus on today’s filmmakers? does that mean?’” and fiction begins (see our Hybrid Forms strand). -

Britten100launched in San Francisco Included in This Issue: Celebrations for Britten’S Centenary in 2013 Include Performances in 140 Cities Around the World

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited October 2012 2012/3 Holloway Britten100launched in San Francisco Included in this issue: Celebrations for Britten’s centenary in 2013 include performances in 140 cities around the world. Robin Holloway travels to Turnage San Francisco on Interview about new works: Highlights in Aldeburgh, where Britten lived including three by the Berliner Philharmoniker 10 January for the world Cello Concerto and Speranza and worked most of his life, include and Simon Rattle. A series of events at premiere of his new performances of Peter Grimes on the beach Carnegie Hall in New York will be announced Debussy song and six new works specially commissioned in early 2013. orchestrations for by the Britten-Pears Foundation and Royal soprano Renée Fleming. New books for the centenary include Paul Philharmonic Society. A week-long festival in Michael Tilson Thomas Kildea’s Benjamin Britten - the first major Glasgow sees Scotland’s four leading Photo: Charlie Troman conducts the San biography for twenty years (Penguin’s Allen orchestras and ensembles come together Francisco Symphony in ten settings of Paul Lane), a collection of rare images from The in April 2013. Verlaine’s poetry, which Holloway has titled Red House archive entitled Britten in Pictures, C’est l’extase after one of the chosen songs. Britten’s global appeal is demonstrated with and the sixth and final volume of Letters from Orchestra and conductor have long territorial premieres of his operas staged in a Life (Boydell & Brewer). BBC Radio and championed Holloway’s music, Brazil, Chile, China, Israel, Russia, Turkey, Television honours Britten with a year-long commissioning a sequence of works Japan and New Zealand. -

City Research Online

Schoeman, Ben (2016). The Piano Works of Stefans Grové (1922-2014): A Study of Stylistic Influences, Technical Elements and Canon Formation in South African Art Music. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) City Research Online Original citation: Schoeman, Ben (2016). The Piano Works of Stefans Grové (1922-2014): A Study of Stylistic Influences, Technical Elements and Canon Formation in South African Art Music. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16579/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. The Piano Works of Stefans Grové (1922-2014): A Study of Stylistic Influences, Technical Elements and Canon Formation in South African Art Music Ben Schoeman Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts City, University of London School of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Music Guildhall School of Music and Drama September 2016 Table of Contents TABLE OF MUSIC EXAMPLES ........................................................................................................................... -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association www.nabmsa.org Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 2016) In this issue: • Cecilia Björkén-Nyberg, The Player Piano and the Edwardian Novel • John Carnelly, George Smart and Nineteenth-Century London Concert Life • Mark Fitzgerald and John O’Flynn, eds., Music and Identity in Ireland and Beyond • Eric Saylor and Christopher M. Scheer, eds., The Sea in the British Musical Imagination • Jürgen Schaarwächter, Two Centuries of British Symphonism: From the Beginnings to 1945 • Heather Windram and Terence Charlston, eds., London Royal College of Music Library, MS 2093 (1660s–1670s) The Player Piano and the Edwardian Novel. Cecilia Björkén-Nyberg. Abingdon, UK and New York: Routledge, 2016. xii+209 pp. ISBN 978-1-47243-998-7 (hardcover). Cecilia Björkén-Nyberg’s monograph The Player Piano and the Edwardian Novel offers an intriguing exploration of the shifting landscape of musical culture at the turn of the twentieth century and its manifestations in Edwardian fiction. The author grounds her argument in musical discussions from such novels as E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View, Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson, and Compton Mackenzie’s Sinister Street. Despite the work’s title, the mechanical player piano is—with rare exception—ostensibly absent from these and other fictional pieces that Björkén-Nyberg considers; however, as the author explains, player pianos were increasingly popular during the early twentieth century and “brought about a change in pianistic behaviour” that extended far beyond the realm of mechanical music making (183). Because of their influence on musical culture more broadly, Björkén-Nyberg argues for the value of recognizing the player piano’s presence in fictional works that otherwise “appear to be pianistically ‘clean’ ” of references to the mechanical instruments. -

Catalogue of Piano Works

ERIK CHISHOLM CATALOGUE OF PIANO WORKS About this catalogue This catalogue has been produced and funded by the Erik Chisholm Trust (ECT), and is on display at the Chisholm web site www.erikchisholm.com All listed music has been typeset by Allan Stephenson, proof-read by Michael Jones and assessed by pianist, Murray McLachlan. The ECT has funded score typesetting, and by the end of 2009 the catalogue will include all Chisholm piano, vocal, choral and string orchestral works. Printed copies of this catalogue can be obtained by written request from the Trust. Score Prices shown are for bound copies; unbound editions are at a reduced rate. Scores can be viewed at the Scottish Music Centre:- Email [email protected] and can be hired from Schott and Co Ltd:- Email [email protected] Acknowledgements The Trust acknowledges with thanks permission granted to use liner notes by Dr John Purser for the Music for Piano CD series and from Murray McLachlan for OCD639, DRD0174 and DRD0219 Chisholm CDs There are 9 commercial CD’s of Chisholm music; Dunelm Records recorded 6 of these with pianist Murray McLachlan whose excellence, energy and enthusiasm make him one of the major propagandists of Chisholm’s music. In April 2008, Jim Pattison, Director of Dunelm Records retired and Stephen Sutton CEO of Divine Art took on the Music for Piano series. In chronological order these CDs are:- CD Number Divine Art Erik Chisholm Piano Music (Olympia) OCD639 Songs for a Year and a Day (Claremont) GSE 1572 Erik Chisholm Piano concerto No 1 DRDO174 Piano Music of Erik Chisholm and Friends DRDO219 Erik Chisholm Music for Piano series DRD0221- 224 DDV131-4 Erik Chisholm Symphony No 2 Dutton Epoch CDLX 7196 All can be ordered from the Chairman of the Trust [email protected] Erik Chisholm Trust The Trust was established in April 2001, granted charitable status in June 2001, and holds the copyright of the published Chisholm works. -

Tocc0262notes.Pdf

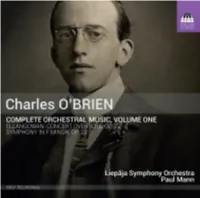

CHARLES O’BRIEN: A SCOTTISH ROMANTIC REDISCOVERED by John Purser Charles O’Brien was born in 1882 in Eastbourne, where his parents, normally based in Edinburgh, were staying for the summer season. His father, Frederick Edward Fitzgerald O’Brien, had worked as a trombonist in the first orchestra to be established in Eastbourne and there, in 1881, he had met and married Elise Ware. They would return there now and again, perhaps to visit her family, whose roots were in France: Elise’s grandfather had been a Girondin who had plotted against Robespierre and, in the words of Charles O’Brien’s son, Sir Frederick,1 ‘had to choose between exile and the guillotine. He chose the former and escaped to England, hence the Eastbourne connection’.2 Elise died tragically in 1919, after being struck by an army vehicle. As well as the trombone, Frederick Edward O’Brien played violin and viola and attempted, unsuccessfully, to teach his grandchildren the violin: ‘it was like snakes and ladders – one minor mistake and we had to start at the beginning again’, Sir Frederick recalled.3 Music went further back in the family than Charles’ father. His grandfather, Charles James O’Brien (1821–76) was also a composer and played the French horn, and his great-grandfather, Cornelius O’Brien (1775 or 1776–1867), who was born in Cork, was principal horn at Covent Garden. Charles O’Brien’s musical education was of the best. One of his early teachers was Thomas Henry Collinson (1858–1928) – father of the Francis Collinson who wrote The Traditional and National Music of Scotland.4 The elder Collinson was organist at St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, as well as conductor of the Edinburgh Choral Union, in which he was succeeded by O’Brien himself.