Entomology in Ecuador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatiotemporal Pattern of Phenology Across Geographic Gradients in Insects

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Spatiotemporal pattern of phenology across geographic gradients in insects Khelifa, Rassim Abstract: Phenology – the timing of recurrent biological events – influences nearly all aspects of ecology and evolution. Phenological shifts have been recorded in a wide range of animals and plants worldwide during the past few decades. Although the phenological responses differ between taxa, they may also vary geographically, especially along gradients such as latitude or elevation. Since changes in phenology have been shown to affect ecology, evolution, human health and the economy, understanding pheno- logical shifts has become a priority. Although phenological shifts have been associated with changes in temperature, there is still little comprehension of the phenology-temperature relationship, particularly the mechanisms influencing its strength and the extent to which it varies geographically. Such ques- tions would ideally be addressed by combining controlled laboratory experiments on thermal response with long-term observational datasets and historical temperature records. Here, I used odonates (drag- onflies and damselflies) and Sepsid scavenger flies to unravel how temperature affects development and phenology at different latitudes and elevations. The main purpose of this thesis is to provide essential knowledge on the factors driving the spatiotemporal phenological dynamics by (1) investigating how phenology changed in time and space across latitude and elevation in northcentral Europe during the past three decades, (2) assessing potential temporal changes in thermal sensitivity of phenology and (3) describing the geographic pattern and usefulness of thermal performance curves in predicting natural responses. -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Review of Entomological Research on Sweet Potato in Ethiopia

Discourse Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences www.resjournals.org/JAFS Vol. 1(5), pp. 83-92, May 2013 Review of Entomological Research on Sweet Potato in Ethiopia Ermias Shonga, Mesele Gemu, Tesfaye Tadesse and Elias Urage Awassa Agricultural Research Centre, Southern Agricultural Research Institute/SARI,P. O. Box 06. Awassa, SNNPR Email : [email protected] Abstract: Sweet potato is one of the most widely grown root crops in SSA, it is particularly important in countries surrounding the Great Lakes in Eastern and Central Africa, in Angola, Madagascar, Malawi and Mozambique in Southern Africa, Nigeria in West Africa and China being the largest producer worldwide. In Africa, it is grown predominantly in small plots by poorer farmers, and hence known as the “poor man’s food.” However it is among well known and established crops in Southern, Eastern and South western parts of Ethiopia. It is produced annually on over 53 thousand hectares of land with total production over 4,240 tons and average productivity of 8.0 tons per hectare. The production and productivity of the crop is extremely low as compared to other African and Asian countries where it gives more than 18t/ha. The lower productivity of sweet potato is mainly due to the existence of common, major, minor and sporadic insect pests. Sweet potato weevil is known as the most pit fall for production and productivity of the crop followed by viral diseases in the country. In addition, sweet potato butter fly is the most devastating pest in major sweet potato growing zones in the country but its occurrence is sporadic based on agro-ecological condition. -

Newly Discovered Sister Lineage Sheds Light on Early Ant Evolution

Newly discovered sister lineage sheds light on early ant evolution Christian Rabeling†‡§, Jeremy M. Brown†¶, and Manfred Verhaagh‡ †Section of Integrative Biology, and ¶Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, University of Texas, 1 University Station C0930, Austin, TX 78712; and ‡Staatliches Museum fu¨r Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Erbprinzenstr. 13, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany Edited by Bert Ho¨lldobler, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, and approved August 4, 2008 (received for review June 27, 2008) Ants are the world’s most conspicuous and important eusocial insects and their diversity, abundance, and extreme behavioral specializations make them a model system for several disciplines within the biological sciences. Here, we report the discovery of a new ant that appears to represent the sister lineage to all extant ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The phylogenetic position of this cryptic predator from the soils of the Amazon rainforest was inferred from several nuclear genes, sequenced from a single leg. Martialis heureka (gen. et sp. nov.) also constitutes the sole representative of a new, morphologically distinct subfamily of ants, the Martialinae (subfam. nov.). Our analyses have reduced the likelihood of long-branch attraction artifacts that have trou- bled previous phylogenetic studies of early-diverging ants and therefore solidify the emerging view that the most basal extant ant lineages are cryptic, hypogaeic foragers. On the basis of morpho- logical and phylogenetic evidence we suggest that these special- EVOLUTION ized subterranean predators are the sole surviving representatives of a highly divergent lineage that arose near the dawn of ant diversification and have persisted in ecologically stable environ- ments like tropical soils over great spans of time. -

The Mesosomal Anatomy of Myrmecia Nigrocincta Workers and Evolutionary Transformations in Formicidae (Hymeno- Ptera)

7719 (1): – 1 2019 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2019. The mesosomal anatomy of Myrmecia nigrocincta workers and evolutionary transformations in Formicidae (Hymeno- ptera) Si-Pei Liu, Adrian Richter, Alexander Stoessel & Rolf Georg Beutel* Institut für Zoologie und Evolutionsforschung, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 07743 Jena, Germany; Si-Pei Liu [[email protected]]; Adrian Richter [[email protected]]; Alexander Stößel [[email protected]]; Rolf Georg Beutel [[email protected]] — * Corresponding author Accepted on December 07, 2018. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/arthropod-systematics on May 17, 2019. Published in print on June 03, 2019. Editors in charge: Andy Sombke & Klaus-Dieter Klass. Abstract. The mesosomal skeletomuscular system of workers of Myrmecia nigrocincta was examined. A broad spectrum of methods was used, including micro-computed tomography combined with computer-based 3D reconstruction. An optimized combination of advanced techniques not only accelerates the acquisition of high quality anatomical data, but also facilitates a very detailed documentation and vi- sualization. This includes fne surface details, complex confgurations of sclerites, and also internal soft parts, for instance muscles with their precise insertion sites. Myrmeciinae have arguably retained a number of plesiomorphic mesosomal features, even though recent mo- lecular phylogenies do not place them close to the root of ants. Our mapping analyses based on previous morphological studies and recent phylogenies revealed few mesosomal apomorphies linking formicid subgroups. Only fve apomorphies were retrieved for the family, and interestingly three of them are missing in Myrmeciinae. Nevertheless, it is apparent that profound mesosomal transformations took place in the early evolution of ants, especially in the fightless workers. -

Collection James Mast De Maeght

Collection James Mast de Maeght Prepared by: Wouter Dekoninck and Stefan Kerkhof Conservator of the Entomological Collections of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels. Collection Information Name: Collection James Mast de Maeght Type of accession: Gift Allocated IG number: IG 33.058 Date of entry in RBINS: 2015/08/18 Date of inscription in RBINS: 2015/12/01 Date of collection inventory: 2015/06/16 1 Background Collection collaborator Alain Drumont (O.D. Taxonomy and Phylogeny) was contacted by James Mast de Maeght with the question whether RBINS might be interested in a donation of a large butterfly collection. The collection of James Mast de Maeght contains worldwide collected butterfly specimens with major focus on the Neotropical fauna and some specific genera like Heliconius, Morpho, Agrias, Prepona and Delias. Many families typical for those regions are well presented (Pieridae, Nymphalidae, Papilionidae, Riodinidae, Lycaenidae). The exact total number of his butterfly collection is somewhere estimated to be around 50.000 specimens. However, for the moment, no detailed list is available. The collection is taxonomically and biogeographically organized. The owner of the collection wants to give his collection in different parts and on several subsequent occasions. The first part, the palearctic collection, will be collected by RBINS staff on the 18 August 2015. Later on the rest of the collection will be collected. This section by section donation is mainly a practical issue of transport, inventory and preparation of the gift by the donator. Fig 1 James Mast de Maeght in front of some of his cabinets of his Neotropical butterfly collection at Ixelles. -

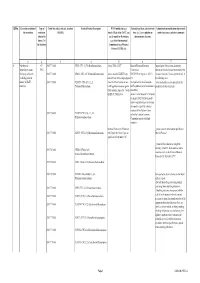

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Subarctic Darner Aeshna Subarctica

Natural Heritage Subarctic Darner & Endangered Species Aeshna subarctica Program State Status: Endangered www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION OF ADULT: The Subarctic Darner is a stunning insect species in the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Aeshnidae (the darners). The adult is a large dragonfly magnificently colored with greens, blues, and rich browns. The thorax (winged and legged segment behind the head) is mostly brown, with two green to blue dorsal stripes and two blue-green to yellowish lateral stripes. The abdominal segments are predominantly brown with green to blue markings. The Subarctic Darner has black legs and transparent to amber-tinged wings. The face is yellow with a thin black cross-line, and the eyes are dull blue- gray to green in color. Subarctic Darners range from 2.6 to almost 3 inches (66-76 mm) in overall length, with the females averaging somewhat larger. Wingspread ranges from 3.1 to 3.6 inches (78-92 mm). SIMILAR SPECIES: Ten species of blue darners (genus Aeshna) occur regularly in Massachusetts and the Subarctic Darner closely resembles many of them in appearance. The slight differences in pattern and and can be distinguished from other Aeshna using coloration distinguish the various species. The face of characteristics as per the keys in Walker (1958). the adult Subarctic Darner is yellow with a black cross- line. In addition, the lateral thoracic stripes are bent HABITAT: Sphagnum bogs and deep fens with wet forward in their upper halves, with the top of the stripe sphagnum. -

Evaluation of the Performance of Improved Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas L

Vol. 8(1), pp. 48-53, January 2014 DOI: 10.5897/AJEST2013. 1572 African Journal of Environmental Science and ISSN 1996-0786 © 2014 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/AJEST Technology Full Length Research Paper Evaluation of the performance of improved sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L. LAM) varieties in Bayelsa State, Nigeria C. Wariboko* and I. A. Ogidi Department of Crop Production Technology, Niger Delta University, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Accepted 11 December, 2013 This study was conducted using randomized complete block design with three replications each in two locations (Amassoma Wilberforce Island and Yenagoa, Bayelsa State) to evaluate the performance of improved sweet potato varieties (Ex-Igbariam, TIS 8164, 199004-2 and TIS 87/0087 including Kukunduku local) from March to June 2010. There were significant differences among varieties at both locations and across locations but locations and location x variety interaction were non-significant for sweet potato root yields. Ex-Igbariam and TIS 87/0087 had higher fresh root yields of 7.39 and 4.17 t ha-1, respectively, than others across locations. Regarding trailing characteristic (soil surface cover), too, varieties were significantly different at both locations and across locations but location and location x variety interaction were non-significant with Ex-Igbariam and TIS 87/0087 having best soil surface cover, and consequently, best weed suppressants. There was incidence of diseases but that of insects was low. For fresh root phenotypic characteristics, Ex-Igbariam and 199004-2 had yellow flesh, indicative of the presence of vitamin A precursor. Since Ex-Igbariam, TIS 87/0087 and a few others showed real promise in yield and carotene content, carrying out a multi-locational trial would, hopefully, enable selection of high - yielding varieties for commercial production to improve farmers’ yields and income in the different agro-ecological zones of Bayelsa State. -

Digging Deeper Into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning Across Two Continents

diversity Article Digging Deeper into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning across Two Continents Mickal Houadria * and Florian Menzel Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, Hanns-Dieter-Hüsch-Weg 15, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Soil fauna is generally understudied compared to above-ground arthropods, and ants are no exception. Here, we compared a primary and a secondary forest each on two continents using four different sampling methods. Winkler sampling, pitfalls, and four types of above- and below-ground baits (dead, crushed insects; melezitose; living termites; living mealworms/grasshoppers) were applied on four plots (4 × 4 grid points) on each site. Although less diverse than Winkler samples and pitfalls, subterranean baits provided a remarkable ant community. Our baiting system provided a large dataset to systematically quantify strata and dietary specialisation in tropical rainforest ants. Compared to above-ground baits, 10–28% of the species at subterranean baits were overall more common (or unique to) below ground, indicating a fauna that was truly specialised to this stratum. Species turnover was particularly high in the primary forests, both concerning above-ground and subterranean baits and between grid points within a site. This suggests that secondary forests are more impoverished, especially concerning their subterranean fauna. Although subterranean ants rarely displayed specific preferences for a bait type, they were in general more specialised than above-ground ants; this was true for entire communities, but also for the same species if they foraged in both strata. Citation: Houadria, M.; Menzel, F. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „UV- und Polarisationssignale bei Tagfaltern“ Verfasserin Sandra Schneider angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Naturwissenschaften (Mag.rer.nat.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 439 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Zoologie (Stzw) UniStG Betreuer: O. Univ.- Prof. Dr. Hannes F. Paulus 1 Für Papa 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagung ............................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 6 Einleitung................................................................................................................................. 7 Material und Methode ...................................................................................................... 14 Untersuchungen am Rasterelektronenmikroskop .................................................. 14 Untersuchung des Schillereffekts aus versch. Betrachtungswinkeln ................. 15 Untersuchung der Polarisationsmuster ..................................................................... 17 Untersuchung der UV-Muster ...................................................................................... 21 Untersuchung zum Thema Wärmeschutz ................................................................. 21 Ergebnisse ............................................................................................................................ -

The Functions and Evolution of Social Fluid Exchange in Ant Colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Marie-Pierre Meurville & Adria C

ISSN 1997-3500 Myrmecological News myrmecologicalnews.org Myrmecol. News 31: 1-30 doi: 10.25849/myrmecol.news_031:001 13 January 2021 Review Article Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Marie-Pierre Meurville & Adria C. LeBoeuf Abstract Trophallaxis is a complex social fluid exchange emblematic of social insects and of ants in particular. Trophallaxis behaviors are present in approximately half of all ant genera, distributed over 11 subfamilies. Across biological life, intra- and inter-species exchanged fluids tend to occur in only the most fitness-relevant behavioral contexts, typically transmitting endogenously produced molecules adapted to exert influence on the receiver’s physiology or behavior. Despite this, many aspects of trophallaxis remain poorly understood, such as the prevalence of the different forms of trophallaxis, the components transmitted, their roles in colony physiology and how these behaviors have evolved. With this review, we define the forms of trophallaxis observed in ants and bring together current knowledge on the mechanics of trophallaxis, the contents of the fluids transmitted, the contexts in which trophallaxis occurs and the roles these behaviors play in colony life. We identify six contexts where trophallaxis occurs: nourishment, short- and long-term decision making, immune defense, social maintenance, aggression, and inoculation and maintenance of the gut microbiota. Though many ideas have been put forth on the evolution of trophallaxis, our analyses support the idea that stomodeal trophallaxis has become a fixed aspect of colony life primarily in species that drink liquid food and, further, that the adoption of this behavior was key for some lineages in establishing ecological dominance.