Nostra Aetate: a Catholic Act of Metanoia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Nostra Aetate After 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time / Edited by Anthony J

EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time Edited by Anthony J. Cernera SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2007 Copyright 2007 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Examining Nostra Aetate after 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in our time / edited by Anthony J. Cernera. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-888112-15-3 1. Judaism–Relations–Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church– Relations–Judaism. 3. Vatican Council (2nd: 1962-1965). Declaratio de ecclesiae habitudine ad religiones non-Christianas. I. Cernera, Anthony J., 1950- BM535. E936 2007 261.2’6–dc22 2007026523 Contents Preface vii Nostra Aetate Revisited Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy 1 The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism Lawrence E. Frizzell 35 A Bridge to New Christian-Jewish Understanding: Nostra Aetate at 40 John T. Pawlikowski 57 Progress in Jewish-Christian Dialogue Mordecai Waxman 78 Landmarks and Landmines in Jewish-Christian Relations Judith Hershcopf Banki 95 Catholics and Jews: Twenty Centuries and Counting Eugene Fisher 106 The Center for Christian-Jewish Understanding of Sacred Heart University: -

Nostra Aetate Catholic Church’S Relation with People of Other Religions

259 The Catholic ChNuorscthr’as AJoeutartnee: y into Dialogue Patrick McInerney* The Declaration (NA) is Vatican II’s ground-breaking document on the Nostra Aetate Catholic Church’s relation with people of other religions. 1 The two previous Popes have called it ‘the Magna Carta’ of the Church’s new direction in interreligious dialogue. 2 For centuries church teaching and practice in regard to other religions had been encapsulated in the axiom extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church no salvation). represents a ‘radically new Nostra Aetate understanding of the relations of the church to the other great world religions.’ 3 * Fr Patrick McInerney LSAI, MTheol, PhD is a Columban missionary priest. Assigned to Pakistan for twenty years, he has a licentiate from the in Rome (1986), a Masters in TheologyP foronmtif itchael MInsetlibtuotuer nfoer C thoell Segtued oy fo Df Aivrianbitiyc (a2n0d0 I3s)l aamndic Ps hD from the Australian Catholic University (2009). He is currently Director of the Columban Mission Institute, Coordinator of its and a staff member of its C. e Hnter el efoctru Crehsr iisnt iamni-sMsioulsoligmy Rate ltahteio ns anCde tnhter eB rfork eMn iBssaiyo nIn Sstiutduites’s In C2a0t1h1o lhiec wInassti tauwtea rodfe Sdy dthnee y title of Honorary Fellow of the CAeunsttrrea lfioanr MCiastshiolnic a Undn iCvuerltsuitrye.. He attends interfaith and multi-faith conferences, and gives talks on Islam, Christian-Muslim Relations and Interreligious Relations to a wide variety of audiences. 1. Vatican II, ‘ : Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions,’ inN ostra Aetate Vatican Council I, I:e dT. -

Benedict XVI and the Interpretation of Vatican II

Cr St 28 (2007) 323-337 Benedict XVI and the Interpretation of Vatican II As the fortieth anniversary of the close of the Second Vatican Council approached, rumors began to spread that Pope Benedict XVI would use the occasion to address the question of the interpretation of the Council. The rumor was particularly promoted by Sandro Ma- gister, columnist of L’Espresso and author of a widely read weekly newsletter on the Internet. For some time Magister had used this newsletter to criticize the five-volume History of Vatican II that had been published under the general editorship of Giuseppe Alberigo. When the last volume of this History appeared, Magister’s newsletter called it a «non-neutral history» (9 Nov. 2001). The role of Giuseppe Dossetti at the Council and the reform-proposals of the Istituto per le Scienze Religiose that he founded were the objects of three separate newsletters (1 Dec. 2003; 3 Jan 2005; 30 Aug. 2005). In a web-article on 22 June 2005, under the title: «Vatican II: The True History Not Yet Told», Magister gave great prominence to the launching of a book presented as a «counterweight» to the Alberigo History. For several years, its author, Agostino Marchetto, had been publishing severely critical reviews of the successive volumes of that History and of several auxiliary volumes generated in the course of the project sponsored by the Bologna Institute. Marchetto had now assembled these review-essays into a large volume entitled Il Conci- lio Ecumenico Vaticano II: Contrappunto per la sua storia and pub- lished by the Vatican Press.1 Magister’s account of the launch of the book gave a good deal of attention to an address by the head of the Italian Bishops’ Confer- 1 A. -

Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology After the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College History Honors Papers History Department 2012 “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wesnousky, Carolyn, "“Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust" (2012). History Honors Papers. 15. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp/15 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust An Honors Thesis Presented by Carolyn Wesnousky To The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut April 26, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………...…………..4 Chapter 1: Living in a Christian World......…………………….….……….15 Chapter 2: The Holocaust Comes to Rome…………………...…………….49 Chapter 3: Preparing the Ground for Change………………….…………...68 Chapter 4: Nostra Aetate before the Second Vatican Council……………..95 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………110 Appendix……………………………………………..……………………114 Bibliography………………………………………………………………..117 2 Acknowledgements As much as I would like to claim sole credit for the effort that went into creating this paper, I need to take a moment and thank the people without whom I never would have seen its creation. -

FULL ISSUE (64 Pp., 3.0 MB PDF)

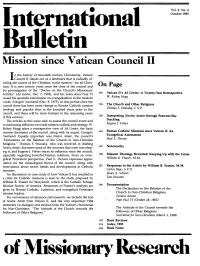

Vol. 9, No.4 nternatlona• October 1985 etln• Mission since Vatican Council II n the history of twentieth-century Christianity, Vatican I Council II stands out as a landmark that is radically af fecting the course of the Christian world mission-for all Chris tians. It is now twenty years since the close of the council and On Page the promulgation of the "Decree on the Church's Missionary Activity" (Ad Gentes, Dec. 7, 1965), and ten years since Paul VI 146 Vatican II's Ad Gentes: A Twenty-Year Retrospective issued his apostolic exhortation on evangelization in the modern W. Richey Hogg world, Evangelii Nuntiandi (Dec. 8, 1975). In this period since the council there has been more change in Roman Catholic mission 154 The Church and Other Religions theology and practice than in the hundred years prior to the Thomas F. Stransky, C.S.P. council, and there will be more ferment in the remaining years of this century. 158 Interpreting Nostra Aetate through Postconciliar The articles in this issue seek to assess the council event and Teaching its continuing influence on world mission outlook and strategy. W. Eugene J. Fisher Richey Hogg takes a retrospective view of Ad Gentes, the basic mission document of the council, along with its sequel, Evangelii 165 Roman Catholic Missions since Vatican II: An Nuntiandi. Equally important was Nostra Aetate, the council's Evangelical Assessment "Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Paul E. Pierson Religions." Thomas F. Stransky, who was involved in drafting Nostra Aetate, discusses some of the concerns that went into shap 167 Noteworthy ing it, and Eugene J. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet. -

Reading Nostra Aetate in Reverse: a Different Way of Looking at the Relationships Among Religions

Reading Nostra Aetate in Reverse: A Different Way of Looking at the Relationships Among Religions Peter C. Phan, Georgetown University If the adage “The best things come in small packages” is ever true, the Second Vatican Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate (NA) surely is an indisputable proof of its truth. This document is neither a “constitution” (dogmatic or pastoral), nor a “decree,” but rather a “declaration,” the lowest rank of the three types of conciliar documents. Vatican II issued four declarations, the other three—on the mass media (Inter Mirifi- ca), religious liberty (Dignitatis Humanae), and Christian education (Gravissimum Educations). With somewhat of an exception for the declaration on religious liberty, they were quickly forgotten. By contrast, NA went on to produce an enormous impact on the life of the Roman Catholic Church and its theology, and that in spite of the fact that it is com- posed of only 1,141 words, in 41 sentences and five paragraphs. “Small packages” indeed! Of course, it may be argued that NA is short because it does not need to provide the theological foundations for its teaching as these have been elaborated at length in the coun- cil’s other documents such as the dogmatic constitution on the church (Lumen Gentium) and the decree on missionary activi- ty (Ad Gentes). While this is true, still those theological foundations do not explain why the declaration has become the cornerstone of and impetus for radical and unexpected developments in both the practice and the theology of interre- ligious dialogue in the Catholic Church in the last fifty years. -

Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church

Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church Editor’s Note: The interventions of Archbishop Viganò and Bishop Schneider have certainly ignited a debate about what the Church should do regarding the problem of Vatican II. Catholic Family News was honored to be asked to publish the English translation of a new intervention on this topic (originally published in Italian here) by Fr. Serafino Maria Lanzetta, a former member of the Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate who is now the Superior of a new community called the Family of Mary Immaculate and St. Francis (established in the Diocese of Portsmouth, England). Father discusses the failure of the “hermeneutic of continuity” offered by Benedict XVI as a solution to the crisis. Benedict’s proposal has always been seen as an ineffective remedy by CFN, but now new voices of critique are being raised around the globe. Archbishop Viganò has declared that it “shipwrecked miserably” and differing proposals to resolve this problem have been brought forward. Fr. Lanzetta provides a helpful explanation and critique of the proposals of Cardinal Brandmüller, Archbishop Viganò, and Bishop Schneider. We at CFN welcome this long-overdue debate and will continue to use our website and monthly paper to promote it and continue the discussion. — Brian M. McCall, Editor-in-Chief ***** Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church By Fr. Serafino M. Lanzetta Recently, the debate about the correct interpretation of the Second Vatican Council has been rekindled. It is true that every council has interpretative problems and very often opens new ones rather than resolving the ones that preceded it. -

ON the Nostra Aetate: a Landmark Document of the Catholic Church's Engagement with Other Religions Batairwa K. Paulin Fu Jen C

ON thE NOStrA AEtAtE: A LANDmArk DOcUmENt OF thE cAthOLic chUrch’S ENgAgEmENt With OthEr RELIGIONS Batairwa K. Paulin Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan ABSTRACT 50 years ago (Dec 8, 1965), at the conclusion of Vatican II, the greatest event marking the life of the Church in the 20th Century, the Roman Catholic Church issued “Nostra Aetate.” The declaration has been a landmark for the Church’s relation and appraisal of other religions. It acknowledged the central role religions play in the history of humanity. Humanity has henceforth, been identified as the concrete platform calling for interactions and cross-fertilization among religions. Religions are to be more united in what they are best at: striving for answers to the existential riddles and sufferings of human persons. For those on the path of dialogue, the 50th anniversary of NA is an opportune occasion to acknowledge shared concerns and learn how respective efforts of religious groups pave the road to more cooperation and mutual enrichment. Introduction Nostra Aetate or the “Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions,” promulgated on October 28, 1965 is the shortest of the sixteen documents of Vatican II. Still, its significance for the development of relations of the Catholic Church with other religions has been unprecedented. As Ariel Ben Ami says, “it was the first time Prajñā Vihāra Vol. 18 No 1, January-June 2017, 1-28 © 2000 by Assumption University Press Batairwa K. Paulin 1 that a council had laid down principles in a solemn way concerning non-Christian religions and recognized in these religions positive values that could be appreciated.” 1 This was in fact to have implications for ways Catholics look and interact with followers of other living faith as well their engagement with existing religious traditions. -

Mysticism and Narcissism

Mysticism and Narcissism Mysticism and Narcissism: A Personal Reflection on Changes in Theology during My Life as a Cenacle Nun By Kathleen Lyons Mysticism and Narcissism: A Personal Reflection on Changes in Theology during My Life as a Cenacle Nun By Kathleen Lyons This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Kathleen Lyons All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8043-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8043-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue ..................................................................................................... ix More than “memoirs” Unfolding of incipient knowledge Reflective writing Heuristic approach Feminist theology Feminism and the psychoanalytic Part I: From Monastic to Apostolic Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Pre-Vatican II Church 1945–62—My Experience of Cenacle Religious Life Modernist crisis Imposition of Neo-Scholastic theology Control by Canon Law The power of the Roman Curia Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 26 -

The Catholic Elites in Brazil and Their Attitude Toward the Jews, 1933–1939* Graciela Ben-Dror

The Catholic Elites in Brazil and Their Attitude Toward the Jews, 1933–1939* Graciela Ben-Dror The 1930s were a decade of sweeping political, social, and economic changes in Brazil. The revolution in 1930 propelled Getúlio Vargas to the presidency;1 there was a distinct political polarization; the general persecution of Communists and the left turned into repression of the same in 1935; and Vargas established an authoritarian state, the Estado Novo (“New State”), in November 1937. All these events affected the attitude of the new political and intellectual elites2 toward the Jewish issue and lent the nascent anti-Jewish climate an additional dimension.3 This climate was abetted by racist ideas that been gestating in Brazil since the late nineteenth century and that had nestled in the consciousness of senior bureaucrats and decision-makers.4 Moreover, a few Brazilian Fascists - members of the Integralist Party, an important movement - helped generate the climate of anti-Jewish hostility by creating the metaphor of the Jew who threatens Brazil and equating Jews with Communists.5 These factors – and 1Boris Fausto, A revolução de 1930 (São Paulo: Editora Brasiliense S. A., 1995, first edition, 1970), pp. 92–114. In this book, one of the most important works on the reasons for the 1930 revolution, Fausto argues that the revolution marked the end of the ruling hegemony of the bourgeoisie at that time. The revolution, prompted by the need to reorganize the country’s economic structure, led to the formation of a regime that arranged compromises among classes and sectors. The military, with its various agencies, became the dominant factor in Brazil’s political development. -

The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Introduction i The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 ii Introduction Introduction iii The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930 –1965 Michael Phayer INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis iv Introduction This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by John Michael Phayer All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and re- cording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri- can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phayer, Michael, date. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 / Michael Phayer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-253-33725-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958—Relations with Jews. 2. Judaism —Relations—Catholic Church. 3. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 5. World War, 1939– 1945—Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 6. Christianity and an- tisemitism—History—20th century. I. Title. BX1378 .P49 2000 282'.09'044—dc21 99-087415 ISBN 0-253-21471-8 (pbk.) 2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 Introduction v C O N T E N T S Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1.