David Cheney's Transcriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

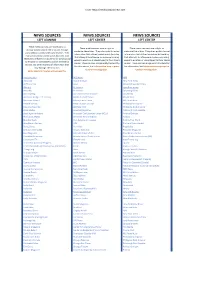

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-08 - PalgraveConnect Tromsoe i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230294981 - From Valmy to Waterloo, Marie-Cecile Thoral War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford, UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming: Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise. -

Analysis of the Front Page of the Houston Post And

ANALYSIS OF THE FRONT PAGE OF THE HOUSTON POST AND HOUSTON CHRONICLE BEFORE AND AFTER THE PURCHASE OF THE HOUSTON POST BY TORONTO SUN PUBLISHING CO. By C. FELICE FUQUA Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1983 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1986 Tk&si~_, l '1 <3'(p F Q, ANALYSIS OF THE FRONT PAGE OF THE AND HOUSTON CHRONICLE BEFORE AND AFTER THE PURCHASE OF THE HOUSTON POST BY TORONTO SUN PUBLISHING CO. Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate Collegec 1251246 ii PREFACE This is a content analysis of the front page news content of the Houston Post and the Houston Chronicle before and after the Post was bought by Toronto Sun Publishing Co. The study sought to determine if the change in ownership of the Post affected the newspaper's content, and if the news content of the Chronicle also had been affected, producing competition between two traditionally noncompetitive newspapers. Many persons made significant contributions to this paper. I would like to express special thanks to my thesis adviser, Dr. Walter J. Ward, director of graduate studies in mass communication at Oklahoma State_ University. I also express my appreciation to the other members of the thesis committee: Dr. Wi~liam R. Steng, professor of journalism and broadcasting, and Dr. Marlan D. Nelson, direc tor of the School of Journalism and Broadcasting. I very much enjoyed working under Dr. Nelson as his graduate assis assistant. -

You Are What You Read

You are what you read? How newspaper readership is related to views BY BOBBY DUFFY AND LAURA ROWDEN MORI's Social Research Institute works closely with national government, local public services and the not-for-profit sector to understand what works in terms of service delivery, to provide robust evidence for policy makers, and to help politicians understand public priorities. Bobby Duffy is a Research Director and Laura Rowden is a Research Executive in MORI’s Social Research Institute. Contents Summary and conclusions 1 National priorities 5 Who reads what 18 Explaining why attitudes vary 22 Trust and influence 28 Summary and conclusions There is disagreement about the extent to which the media reflect or form opinions. Some believe that they set the agenda but do not tell people what to think about any particular issue, some (often the media themselves) suggest that their power has been overplayed and they mostly just reflect the concerns of the public or other interests, while others suggest they have enormous influence. It is this last view that has gained most support recently. It is argued that as we have become more isolated from each other the media plays a more important role in informing us. At the same time the distinction between reporting and comment has been blurred, and the scope for shaping opinions is therefore greater than ever. Some believe that newspapers have also become more proactive, picking up or even instigating campaigns on single issues of public concern, such as fuel duty or Clause 28. This study aims to shed some more light on newspaper influence, by examining how responses to a key question – what people see as the most important issues facing Britain – vary between readers of different newspapers. -

Jane Stabler, “Religious Liberty in the 'Liberal,' 1822-23”

Jane Stabler, Religious Liberty in the Lib... http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=jane-stabler-religious-liberty-in-the-liberal Jane Stabler, “Religious Liberty in the ‘Liberal,’ 1822-23” Figure 1: Thomas Philipps, Portrait of Lord Byron (1824) To think about the Liberal as an important event is to enter contentious territory. William Hazlitt (who was a contributor) described the journal as “obnoxious” in its day (Complete Works 12. 379), and in the following century, it was usually regarded as a failure or, at least, a disappointment—something that never really came together before it fell apart. In 1910, Barnette Miller described it as “a vague, up-in-the-air scheme, wholly lacking in coordination and common sense” (113). Metaphors of death and still-birth pervade the twentieth-century criticism: according to C. L. Cline “The Liberal died with the fourth number” (247); Leslie P. Pickering summarises the project thus: “in as meteoric a manner as it lived, so did the journal die, bearing with it to its untimely grave the ruined hopes of its progenitors, until now its name conveys but little to the minds of the many” (7-8). The seminal study by William H. Marshall declared, “the real question does not concern the causes of the failure of The Liberal but the reason that any of the participants thought that it could succeed” (212). In Richard Holmes’s biography of Shelley, the journal “folded quietly . after only four issues, the final collapse of Shelley’s original Pisan plan” (731); in Fiona MacCarthy’s biography of Byron, the Liberal was a “critical and financial disaster” and, after Byron’s final contribution, it simply “folded” (456). -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

Tabloid Media Campaigns and Public Opinion: Quasi-Experimental Evidence on Euroscepticism in England

Tabloid media campaigns and public opinion: Quasi-experimental evidence on Euroscepticism in England Florian Foos London School of Economics & Political Science Daniel Bischof University of Zurich March 3, 2021 Abstract Whether powerful media outlets have eects on public opinion has been at the heart of theoret- ical and empirical discussions about the media’s role in political life. Yet, the eects of media campaigns are dicult to study because citizens self-select into media consumption. Using a quasi-experiment – the 30-years boycott of the most important Eurosceptic tabloid newspaper, The Sun, in Merseyside caused by the Hillsborough soccer disaster – we identify the eects of The Sun boycott on attitudes towards leaving the EU. Dierence-in-dierences designs using public opinion data spanning three decades, supplemented by referendum results, show that the boycott caused EU attitudes to become more positive in treated areas. This eect is driven by cohorts socialised under the boycott, and by working class voters who stopped reading The Sun. Our findings have implications for our understanding of public opinion, media influence, and ways to counter such influence, in contemporary democracies. abstract=150 words; full manuscript (excluding abstract)=11,915 words. corresponding author: Florian Foos, [email protected]. Assistant Professor in Political Behaviour, Department of Govern- ment, London School of Economics & Political Science. Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, UK. Phone: +44 (0)7491976187. Daniel Bischof, SNF Ambizione Grant Holder, Department of Political Science, University of Zurich. Aolternstrasse 56, 8050 Zurich, CH. Phone: +41 (0)44 634 58 50. Both authors contributed equally to this paper; the order of the authors’ names reflects the principle of rotation. -

After Somerset: the Scottish Experience', Journal of Legal History, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer After Somerset Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2012, 'After Somerset: The Scottish Experience', Journal of Legal History, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 291-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Legal History Publisher Rights Statement: © Cairns, J. (2012). After Somerset: The Scottish Experience. Journal of Legal History, 33(3), 291-312. 10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 After Somerset: The Scottish Experience JOHN W. CAIRNS The Scottish evidence examined here demonstrates the power of the popular understanding that, in Somerset’s Case (1772), Lord Mansfield had freed the slaves, and shows how the rapid spread of this view through newspapers, magazines, and more personal communications, encouraged those held as slaves in Scotland to believe that Lord Mansfield had freed them - at least if they reached England. -

Byron and Leigh Hunt: “The Wit in the Dungeon”1

Leigh Hunt 1 1 BYRON AND LEIGH HUNT: “THE WIT IN THE DUNGEON” [Italicised passages are from Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron and some of his Contemporaries (“L.B.” here and in the notes) 2 vols, 1828.] 1) England It’s in the nature of dungeons to make their occupants seem more interesting than they appear when they’re freed. I remember two victimised theatre-performers whom the Soviets prevented from emigrating for years and years, and who were blown up by their western supporters into stifled geniuses. They were freed – put on their first show … and were promptly forgotten. I saw nothing in Lord Byron at that time, but a young man who, like myself, had written a bad volume of poems – Hunt on his first sighting of Byron, swimming, in 1812. L.B. p.2. What drew Byron’s initial attention to James Henry Leigh Hunt was Hunt’s imprisonment for libelling the Prince Regent in The Examiner, the Sunday paper he and his very different brother John edited, and in part wrote. The Prince, wrote Hunt (among much else), … was a violator of his word, a libertine over head and ears in debt and disgrace, a despiser of domestic ties, the companion of gamblers and demireps, a man who has just closed half a century without one single claim on the gratitude of his country or the respect of posterity!2 This was published on March 22nd 1812, less than a month after Byron’s Lords speech on the Luddites, which was given on February 27th, and a month before his Roman Catholic Claims speech, which was given on April 22nd.