Ecocriticism & Irish Poetry a Preliminary Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

The Gallery Press

The Gallery Press The Gallery Press’s contribu - The Gallery Press has an unrivalled track record in publishing the tion to the cultural life of this first and subsequent collections of poems by now established Irish country is ines timable. The title poets such as Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Eamon Grennan, ‘national treasure’ is these days Michael Coady, Dermot Healy, Frank McGuinness and Peter conferred, facetiously for the Sirr . It has fostered whole generations of younger poets it pub - most part, on almost any old lished first including Ciaran Berry, Tom French, Alan Gillis, thing — person or institution — Vona Groarke, Conor O’Callaghan, John McAuliffe, Kerry but The Gallery Press truly is an Hardie, David Wheatley, Michelle O’Sullivan and Andrew enterprise to be treasured by the Jamison . It has also published seminal career-establishing titles nation. by Ciaran Carson, Paula Meehan, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, — John Banville Justin Quinn, Seán Lysaght and Gerald Dawe . The Press has published books by Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon and John Banville and repatriated authors such as Brian Friel, Derek Peter Fallon’s Gallery Press is the Mahon and Medbh McGuckian who previously turned to living fulcrum around which the London and Oxford as a publishing outlet. swarm ing life of contemporary Irish poetry rotates. Fallon’s is a Gallery publishes the work of Ireland’s leading women poets truly extraordinary Irish life, and and playwrights including Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Nuala Ní it goes on still, unabated. Dhomhnaill, Medbh McGuckian, Michelle O’Sullivan, Sara — Thomas McCarthy, Irish Berkeley Tolchin, Vona Groarke, Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh, Literary Supplement Aifric MacAodha and Marina Carr . -

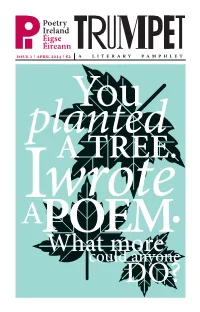

Issue 6 April 2017 a Literary Pamphlet €4

issue 6 april 2017 a literary pamphlet €4 —1— Denaturation Jean Bleakney from selected poems (templar poetry, 2016) INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster camouflaging the house-number. Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date shade card known by heart. It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; although, according to a botanist, for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. But surely every biological system has its limits? There’s no going back for egg white once it’s hit the fat. Yet, some people seem determined to stretch, to redefine those limits. Why are they so inclined? —2— INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle by Thomas McCarthy (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster Tara Bergin This is Yarrow camouflaging the house-number. carcanet press, 2013 Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date Jane Clarke The River shade card known by heart. bloodaxe books, 2015 It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; Adam Crothers Several Deer although, according to a botanist, carcanet press, 2016 for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. -

Precursors, the Environment and the West in Seamus Heaney’S “Postscript”

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 13, March 2018-Feb. 2019, pp. 69-81 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI Precursors, the Environment and the West in Seamus Heaney’s “Postscript” Ross Moore Independent scholar, Belfast Copyright (c) 2018 by Ross Moore. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. Being the final poem in Heaney’s 1996 collection The Spirit Level, situates the poem “Postscript” significantly in Heaney’s poetic oeuvre. The collection was Heaney’s first to be published after winning the Nobel Prize for literature, it was also his first published amidst the changed social and political context following the 1994 paramilitary ceasefires in Northern Ireland. Here, I will explore the manner in which “Postscript” interacts with previous work by Heaney. Looking closely at the language, imagery and procedures of the poem, I argue that the poem embodies a fundamental shift in Heaney's approach to the natural environment but that this change is reliant on poetic procedures which Heaney had come to trust early in his career. Heaney's descriptive precision and openness to the “marvellous” combine to produce a uniquely effective poem. “Postscript” treats the natural world and the human subject in a manner atypical of Heaney's procedures yet stands among his most accomplished work. I will consider the manner in which Heaney's poem simultaneously exists “post” the “scripts” of literature mythologizing the West of Ireland while remaining in close dialogue with perhaps the most famous of these: Yeats's poem “The Wild Swans at Coole”. -

What More Could Anyone Do?

issue 1 / april 2014 / €2 a literary pamphlet You planted A TREE. Iwrote APOEM. Whatcould more anyone DO? My father, the least happy man I have known. His face retained the pallor The of those who work underground: the lost years in Brooklyn listening to a subway shudder the earth. Cage But a traditional Irishman who (released from his grille John Montague in the Clark Street IRT) drank neat whiskey until from new collected poems he reached the only element (the gallery press, 2012) he felt at home in any longer: brute oblivion. And yet picked himself up, most mornings, to march down the street extending his smile to all sides of the good, (all-white) neighbourhood belled by St Teresa's church. When he came back we walked together across fields of Garvaghey to see hawthorn on the summer hedges, as though he had never left; a bend in the road which still sheltered primroses. But we did not smile in the shared complicity of a dream, for when weary Odysseus returns Telemachus should leave. Often as I descend into subway or underground I see his bald head behind the bars of the small booth; the mark of an old car accident beating on his ghostly forehead. —2— 21 74 Sc ience and W onder by Richard Hayes Iggy McGovern A Mystic Dream of 4 quaternia press, €11.50 Iggy McGovern’s A Mystic Dream of 4 is an ambitious sonnet sequence based on the life of mathematician William Rowan Hamilton. Hamilton was one of the foremost scientists of his day, was appointed the Chair of Astronomy in Dublin University (Trinity College) while in the final year of his degree, and was knighted in 1835. -

SAMPLER a Line of Tiny Zeros in the Fabric

A Line of Tiny Zeros in the Fabric SAMPLER SAMPLER A Line of Tiny Zeros in the Fabric Essays on the Poetry of Maurice Scully SAMPLER edited by Kenneth Keating Shearsman Books First published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by Shearsman Books Ltd PO Box 4239 Swindon SN3 9FN Shearsman Books Ltd Registered Office 30–31 St. James Place, Mangotsfield, Bristol BS16 9JB (this address not for correspondence) ISBN 978-1-84861-729-2 Copyright © 2020 by the authors. The right of the persons listed on page 5 and 6 to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act of 1988. All rights reserved. Acknowledgements ‘A Line of Tiny Zeros in the Fabric’ is from ‘Song’, in Humming, p. 93. An earlier version of the essay by Kit Fryatt was published as ‘“AW.DAH.”: an allegorical reading of Maurice Scully’s Things That Happen’ in POST: A Review of Poetry Studies 1 (2008). Many thanks to the editors of this journal for permitting theSAMPLER reproduction of this text here. Note Page numbers of poetic texts referenced parenthetically in the essays herein refer to editions of the texts as identified in the respective lists of Works Cited. On occasion however, the texts presented here may vary slightly from their earlier appearances. These revisions reflect minor changes made by Maurice Scully in the new complete edition of Things That Happen, which is published simultaneously with this collection of essays. The decision was made to reflect these corrections in the essays, but to retain the original citations and acknowledge the original publishers of the texts in question. -

Irish Studies Around the World – 2020

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 238-283 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10080 _________________________________________________________________________AEDEI IRISH STUDIES AROUND THE WORLD – 2020 Maureen O’Connor (ed.) Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction Maureen O’Connor ............................................................................................................... 240 Cultural Memory in Seamus Heaney’s Late Work Joanne Piavanini Charles Armstrong ................................................................................................................ 243 Fine Meshwork: Philip Roth, Edna O’Brien, and Jewish-Irish Literature Dan O’Brien George Bornstein .................................................................................................................. 247 Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the 20th Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives Edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney Deirdre F. Brady ..................................................................................................................... 250 English Language Poets in University College Cork, 1970-1980 Clíona Ní Ríordáin Lucy Collins ........................................................................................................................ 253 The Theater and Films of Conor McPherson: Conspicuous Communities Eamon -

Triskele Fall 2004.Pmd

TRISKELE A newsletter of UWM’s Center for Celtic Studies Volume III, Issue II Samhain, 2004 Fáilte! Croeso! Mannbet! Kroesan! Fair Faa Ye! Welcome! Midwest ACIS Comes to Milwaukee The annual Midwest Regional meeting of the American Conference for Irish Studies (ACIS) was held on the UWM campus from Thursday, October 14, through Saturday, October 16. ACIS is an interdisciplinary scholarly organization founded in 1960. The conference was organized by José Lanters, Nancy Walczyk, and John Gleeson, under the auspices of the Center for Celtic Studies. On Thursday evening, the meeting kicked off in great style with a reception for the delegates in County Clare Irish Inn, with Irish music by Cé. In the course of the evening, James Liddy’s autobiography, The Doctor’s House (Salmon Press, 2004), fresh off the plane from Ireland, was launched, read from, toasted, sold, and sanctioned by the presence of emeritus archbishop Rembert Weakland, who had joined us for the occasion. Friday was a full day, with an exciting academic program of eight panels of four speakers each, on topics ranging from literature and history to music, art and politics. Professor Seamus Caulfield’s Frank Gleeson, Tom Kilroy, James Liddy, plenary lecture, “Neolithic Rocks to Riverdance,” accompanied by Jose Lanters, Josephine Craven, Joe slides and presented with verve and humor, gave his enthusiastic Dowling and Eamonn O’Neill audience an insight into the many and varied aspects of the archaeological excavations at Céide Fields in Co. Mayo. A reception at the Irish Cultural and Heritage Center, hosted by Charles Sheehan, Irish Consulate of Chicago, concluded the day, and included even more delights, in the form of James Fraher’s photographic images of Ireland, and enchanting music by Melanie O’Reilly and Seán O Nualláin. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Contents Poetry Ireland Review 133

Contents Poetry Ireland Review 133 Colette Bryce 5 editorial Vona Groarke 7 under a tree, parked 8 daily news round-up 9 for now Ella Duffy 10 rumour Edward Larrissy 11 london, june 2016 Majella Kelly 13 the secret wife of jesus 15 fig Mícheál McCann 16 immanence 17 big city types Kimberly Reyes 18 stain in creases Kerry Hardie 20 insomnia in talbot street Damian Smyth 21 keats’s bed Tamara Barnett-Herrin 22 soft play 24 hi! is this for me? Thomas McCarthy 25 a meadow in july Bernard O’Donoghue 26 l’aiuola 27 the impulsator Siobhán Campbell 28 the outhouse Tim MacGabhann 29 morelia ghosts Grace Wilentz 32 essay: towards a first collection Katie Donovan 34 review: matthew sweeney, michael gorman, geraldine mills Hugh Haughton 38 essay: derek mahon Frank Farrelly 45 essay: towards a first collection Niamh NicGhabhann 47 review: pádraig j daly, eamon grennan, kerry hardie, julie o’callaghan Stephen Sexton 52 essay: towards a first collection Declan Ryan 54 review: alan gillis, justin quinn Proinsias Ó Drisceoil 58 review: seán ó ríordáin / greg delanty, fearghas macfhionnlaigh / simon ó faoláin Seosamh Ó Murchú 61 cogar caillí Bríd Ní Mhóráin 62 ialus Áine Ní Ghlinn 63 droim mo mháthar Ceaití Ní Bheildiúin 64 saolú mhongáin Simon Ó Faoláin 65 as an corrmhíol Máirtín Coilféir 66 ping Seán Lysaght 67 review: cathal ó searcaigh Maria Stepanova 70 from the body returns Maurice Riordan 74 gravel 75 mould 76 lumps David McLoghlin 77 independent commission for the location of victims’ silence Emily Middleton 78 misloaded Bryony Littlefair 80 typo -

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960 In 1936, writing in the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, W.B. Yeats felt the need to stake a claim for the distance of art from popular political concerns; poets’ loyalty was to their art and not to the common man: Occasionally at some evening party some young woman asked a poet what he thought of strikes, or declared that to paint pictures or write poetry at such a moment was to resemble the fiddler Nero [...] We poets continued to write verse and read it out at the ‘Cheshire Cheese’, convinced that to take part in such movements would be only less disgraceful than to write for the newspapers.1 Yeats was, of course, striking a controversial pose here. Despite his famously refusing to sign a public letter of support for Carl von Ossietzky on similar apolitical grounds, Yeats was a decidedly political poet, as his flirtation with the Blueshirt movement will attest.2 The political engagement mocked by Yeats is present in the Irish working-class writers who produced a range of poetry from the popular ballads of the socialist left, best embodied by James Connolly, to the urban bucolic that is Patrick Kavanagh’s late canal-bank poetry. Their work, whilst varied in scope and form, was engaged with the politics of its time. In it, the nature of the term working class itself is contested. This conflicted identity politics has been a long- standing feature of Irish poetry, with a whole range of writers seeking to appropriate the voice of ‘The Plain People of Ireland’ for their own political and artistic ends.3 1 W.B. -

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry Module type Optional (approved module: MPhil in Irish Writing) Term / hours Hilary / 22 ECTS 10 Coordinator(s) Dr Rosie Lavan ([email protected]) Dr Tom Walker ([email protected]) Lecturer(s) Dr Rosie Lavan Dr Tom Walker Cap Depending on demand Module description Eavan Boland is one of the most significant Irish poets of the past century. In a career of more than 50 years, she persistently questioned, and radically expanded, the parameters of Irish poetry and the definition of the Irish poet. The course will examine a wide range of Eavan Boland’s poetry and prose. Seminars are structured around some of the poet’s major themes and modes. These will also be interspersed with seminars that seek to place Boland within the broader history of modern Irish poetry, via comparisons with the work and careers of Blanaid Salkeld, Patrick Kavanagh, Derek Mahon, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Paula Meehan. Also explored will be relevant historical and cultural contexts, and questions of poetics and ideology. Assessment The module is assessed through a 4,000-word essay. Indicative bibliography Students will need to purchase a copy of Eavan Boland, New Selected Poems (Carcanet/Norton) and Eavan Boland, Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time (Carcanet/Vintage/Norton) as the core course texts. Please note: it is expected that students will read Object Lessons in full before the start of the course. All other primary material needed through the term will be made available via Blackboard. This will include poems from Boland’s collections published since the appearance of New Collected Poems (Domestic Violence, A Woman Without A Country and The Historians) and the work of the other poets to be studied on the course, as well as various other relevant essays, articles and interviews.