Abstract: Stepping Back from the Wall: Narratives of Lives Lost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

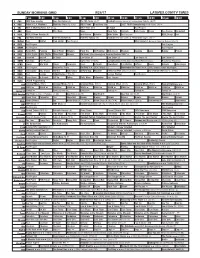

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

May 16, 2012 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 16, 2012 • VOL. 23, NO. 2 $1.25 Congratulations to Ice Pool Winner KLONDIKE Mandy Johnson. SUN Breakup Comes Early this Year Joyce Caley and Glenda Bolt hold up the Ice Pool Clock for everyone to see. See story on page 3. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue SOVA Graduation 18 Andy Plays the Blues 21 The Happy Wanderer 22 Summer 2012 Year Five had a very close group of The autoharp is just one of Andy Paul Marcotte takes a tumble. students. Cohen's many instruments. Store Hours See & Do in Dawson 2 AYC Coverage 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 DCMF Profile 19 Kids' Corner 26 Uffish Thoughts 4 TV Guide 12-16 Just Al's Opinion 20 Classifieds 27 Problems at Parks 5 RSS Student Awards 17 Highland Games Profiles 24 City of Dawson 28 P2 WEDNESDAY, May 16, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to close. More live entertainment in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 SEE AND DO p.m.The toDowntown 8:30 p.m. Hotel LIVE MUSIC: - in DAWSON now: Barnacle Bob is now playing in the Sourdough Saloon ev eryThe Thursday, Eldorado Friday Hotel and Saturday from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may Food Service Hours: 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., seven days a week. Check out need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To our Daily Lunch Specials. -

Mazzaoui – “Medieval Warfare”

University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of History Semester I, 2010-11 H 200 Medieval Warfare M. Mazzaoui Required Textbooks: Winthrop Lindsay Adams, Alexander The Great (Pearson Longman PB) Kelly DeVries, Medieval Military Technology (Toronto PB) Michael Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience (Yale PB) Helen Nicholson and David Nicolle, God’s Warriors: Knights Templar, Saracens and the Battle for Jerusalem (Osprey PB) A useful reference work: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology ed, Clifford J. Rogers Assignments include Decisive Battles Series and Battles BC on YouTube (DB and BC). Course Requirements: Three credits. Three essay examinations: two midterms and final, non-cumulative. N.B. Regular attendance is expected. Excessive absence may have a negative impact on your final grade. LECTURE SCHEDULE 9/2 Introduction: Military Technology in the Ancient World DeVries, pp. 3-6, 44-47; Prestwich, ch. 1, ch. 2, pp. 30-37 9/7 Ancient Warfare: Battle of Qadesh (1294 B.C.); Siege of Troy DB: Ramses II 9/9-14 The Greek Phalanx; Battle of Marathon Sparta, A Warrior Society; Thermopylae DeVries, pp. 7-20, 25-33, 50-52, 125-132; DB: Marathon, Thermopylae; BC: Judgement Day atMarathon 9/16-21 Alexander of Macedon Adams, chs, 1-5; DB: Gaugamela 9/23-28 The Roman Legions; The Punic Wars; Battle of Cynocephalo DeVries pp. 52-55, 125-132, 174-187; DB: Cannae; Birth of the Roman Empire 9/30-10/5 Celtic Warriors: Vercingetorix; Boudica DeVries, pp. 56-58; DB: Hail Caesar 10/7 SIX-WEEKS EXAMINATION 10/12-14 Roman Limes and Germanic Tribes; Huns; Gothic Invasion: Battle of Adrianople DeVries, pp. -

Obres Audiovisuals Qualificades En Format No Cinematogràfic Resolució Gener 2010

OBRES AUDIOVISUALS QUALIFICADES EN FORMAT NO CINEMATOGRÀFIC RESOLUCIÓ GENER 2010 TÍTOL COMERCIAL TÍTOL ORIGINAL Núm. Exp. Qualific. Empresa Data resol Data cad. OCEANWORLD 3D Oceanworld 3D 115493 ERI Cameo Media, SL 20/01/2010 25/12/2017 BEAR GRYLLS, EL ÚLTIMO SUPERVIVIENTE Man vs. wild 115264 TP Track Media, SL 15/01/2010 30/11/2011 PLANETA TIERRA: OCEANO AZUL South Pacific 115356 TP Savor Ediciones, SA 18/01/2010 24/03/2014 EL CIELORETORNO PUEDE DEL ESPERAR SOLDADO The return of the soldier 115486 TP Seven Art Pictures, SLU 15/01/2010 27/05/2020 PERO LA MUJER DE O'HARA NO O'Hara wife 115491 TP Seven Art Pictures, SLU 15/01/2010 10/05/2021 Sociedad General de FILIGRANA Filigrana 115550 TP Derechos Audiovisuales, SA 27/01/2010 13/02/2011 Sociedad General de MIENTRAS SEAN FELICES As long as they're happy 115562 TP Derechos Audiovisuales, SA 27/01/2010 31/12/2017 JUANA DE PARIS Joan of Paris 115596 TP Sogemedia, SL 18/01/2010 03/02/2023 EL MUNDO DE LAS TERAPIAS, El mundo de las terapias, DVD 13-16 dvd 13-16 115625 TP O.K. Records, S.L. 18/01/2010 23/10/2014 PORTUGAL, EL MIRADOR DEL ATLÁNTICO Portugal 115670 TP RBA Edipresse, SL 21/01/2010 19/01/2011 LOS MANUSCRITOS DEL MAR Riddles of the Bible: Sea MUERTO scrolls 115671 TP RBA Publicaciones, SL 21/01/2010 31/12/2012 EN EL VIENTRE MATERNO In the womb 115698 TP Track Media, SL 27/01/2010 01/12/2014 Inversiones Derechos SALSA Salsa 115729 TP Audiovisuales, SL 21/01/2010 07/03/2015 BUSCANDO A ERIC Buscando a Eric 115797 TP Cameo Media, SL 28/01/2010 27/02/2018 ULTIMOS TESTIGOS Ultimos testigos -

DISH Network® Premieres Interactive Television Experience for New History Series BATTLES BC

DISH Network® Premieres Interactive Television Experience for New History Series BATTLES BC DISH Network iTV Platform Launches HISTORY Interactive Which Provides Viewers With Interactivity 24/7; Content-Synchronized Quizzes, Games & Photo Gallery to Test Audiences' Knowledge of Historical Events ENGLEWOOD, CO and NEW YORK, NY, Mar 09, 2009 (MARKET WIRE via COMTEX News Network) -- Today, DISH Network® announced the launch of HISTORY™ Interactive, an enhanced 24/7 interactive television (iTV) experience. Produced exclusively by DISH Network and developed by HISTORY and Ensequence, HISTORY Interactive offers a range of features including history factoids, daily questions related to HISTORY's programming content, and the ability to set DVR timers and recorders for upcoming HISTORY shows. With help from Ensequence, the interactive experience will also be integrated into HISTORY's new TV series BATTLES BC, which premieres on Monday, March 9 at 9:00 p.m. ET/PT. DISH Network subscribers must have an OpenTV-enabled receiver to use the iTV application. BATTLES BC uses a stunning graphic style comparable to "300," the hit feature film, to show leaders from the ancient world in some of the greatest conflicts in history. The series brings to life the strategies, tactics and weapons used by commanders such as Hannibal, Moses, Alexander and David, and also exposes the truths and myths behind the ancient world of epic heroes and villains. DISH Network and HISTORY, along with Ensequence, partnered to create interactive experiences for the new BATTLES BC program. Throughout each episode, viewers' knowledge of the battle strategies that shaped ancient history will be tested. Using a DISH Network remote control, HISTORY viewers will be able to access information, review the biographies and credentials of on-camera historical experts, and view a gallery of images highlighting the production aspects of the program series. -

P32 Layout 1

32 Friday TV Listings Friday, November 1, 2019 03:45 Live PD: Police Patrol 21:35 Breaking Magic 20:15 Wheeler Dealers 11:30 UFO Hunters 04:10 Live PD: Police Patrol 22:00 Tricks On The Streets 21:00 Salvage Hunters: Classic 12:15 Battles BC 04:30 The First 48 22:25 Tricks On The Streets Cars 13:00 Modern Marvels 05:15 Homicide Hunter 22:50 Keeping Up With The Kruger 00:00 Sofia The First 21:50 Aaron Needs A Job 13:45 Serial Killer Earth 00:05 Crank 06:00 Homicide: Hours To Kill 23:40 Tanked 00:25 Disney Junior Music Nursery 22:40 Dirty Mudder Truckers 14:30 Clash Of The Gods 01:40 Leatherface 07:00 Live PD: Police Patrol Rhymes 23:30 Deadliest Catch 15:15 Ancient Aliens 03:15 Painted Skin: The Resurrec- 07:20 The First 48 00:30 Gigantosaurus 16:00 Deep Sea Salvage tion 08:05 The First 48 01:00 PJ Masks 16:45 UFO Hunters 05:35 Kung Fu Yoga 08:50 Homicide Hunter 01:25 PJ Masks 17:30 Battles BC 07:35 The Monkey King 09:35 Homicide Hunter 01:50 Paprika 18:15 America’s Book Of Secrets 09:40 The Taking Of Pelham 123 10:30 Homicide: Hours To Kill 00:00 True Nightmares 02:00 Zou 19:00 Search For The Lost Giants 11:40 Stargate 11:25 What The Killer Did Next 01:00 The Real Story With Maria 02:15 Zou 00:10 Randy Cunningham: 9th 19:45 Serial Killer Earth 13:45 Tai Chi 2: The Hero Rises 12:20 Crimes That Shook Britain Elena Salinas 02:30 Henry Hugglemonster Grade Ninja 20:30 Clash Of The Gods 15:40 American Ninja III 13:15 Live PD: Police Patrol 02:00 Deadline: Crime With Tam- 02:55 Henry Hugglemonster 01:00 Boyster 21:15 Ancient Aliens 17:25 Transformers: -

P32 Layout 1

32 Friday TV Listings Friday, July 5, 2019 16:00 The First 48 06:10 Blood Relatives 12:40 Mickey And The Roadster 10:25 Kick Buttowski 05:30 Jurassic Fight Club 17:00 Homicide: Hours To Kill 07:00 Killer Instinct With Chris Racers S1 Splits 10:50 Phineas And Ferb 06:15 Million Dollar Genius 18:00 Crimes That Shook Britain Hansen 13:00 Fancy Nancy Splits S1 11:00 Gravity Falls 07:00 UFO Hunters 19:00 The First 48 08:50 Deadly Secrets 14:00 Vampirina S1 11:25 Gravity Falls 07:45 Cities Of The Underworld 01:25 The Unseen 20:00 Homicide Hunter 09:45 Deadly Secrets 15:00 Gigantosaurus S1 Splits 11:50 Milo Murphy’s Law 08:30 Ancient Impossible 03:20 Patriots Day 21:00 Live PD: Police Patrol 10:40 Disappeared 15:55 Toy Story Toons 12:05 Marvel’s Avengers: Black 09:15 Ancient Aliens 05:35 Andron 22:00 The Jail: 60 Days In 11:35 Murder Chose Me 16:00 The Lion Guard Panther’s Quest 10:00 Ancient Aliens 07:20 Around The World In 80 23:00 Live PD: Police Patrol 12:30 Murder Chose Me 16:30 Elena Of Avalor 12:30 Supa Strikas 10:45 Battles BC Days 13:25 Blood Relatives 17:00 Gigantosaurus S1 13:20 Lab Rats 11:30 Jurassic Fight Club 09:20 Thor: The Dark World 14:20 Reasonable Doubt 17:25 Mickey And The Roadster 14:10 Pair Of Kings 12:15 Million Dollar Genius 11:15 Andron 15:15 Deadly Secrets Racers - Chip And Dale’s 15:00 Marvel’s Spider-Man 13:00 UFO Hunters 12:55 Boone: The Bounty Hunter 16:10 Disappeared 17:30 Mickey And The Roadster 15:25 Disney Mickey Mouse 13:45 Cities Of The Underworld 14:25 The Drowning 00:20 Rocketman 17:05 Breaking Homicide -

Lucan's Bellum Ciuile and the Epic Genre

Lucan’s Bellum Ciuile and the Epic Genre Fran Alexis BA (Hons) MA This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Classics University of Tasmania 2011 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Fran Alexis Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Fran Alexis iii Lucan’s Bellum Ciuile and the Epic Genre Abstract This thesis demonstrates that Lucan’s Bellum Ciuile takes epic to a new level, testing the generic paradigm, because Rome’s civil war is a new subject for epic poetry. Lucan’s epic presents civil war as the self-destruction of republican Rome, and close reading reveals the poem’s intricate relationship with Homeric, Virgilian and Ovidian epic. We see that it changes and exaggerates characteristic tropes of the genre, by techniques such as delay, digression and frequent intervention by a complex narrator / persona, whose dramatic intrusions are like the speeches of characters in a tragedy. Such a politically risky subject, a type of impious war where Romans fight against and kill Romans, necessitates a long preamble and an insistent narrator’s voice to justify poetic commemoration of such a crime. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

March 21, 2012 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, MARCH 21, 2012 • VOL. 24, NO. 23 $1.25 Did you freeze at KLONDIKE Thaw di Gras? SUN Rangers Receive Service Awards (Above) Six and 12-year ranger veterans. Rangers assemble for the Operation Mate Graduation. See Page 6. Photos by Dan Davidson in this Issue Max’s has all the Trek Over the Top 3 The Happy Writer 7 Larry's Reading 20 Easter candy It took him 19 years to come in first Why is this man smiling? What brought all these people to the place Library? you could ever want! See & Do in Dawson 2 School Carnivale Pix 5 Reconciliation Musings 15 Mann Lecture 17 Uffish Thoughts 4 CO2 Warning 9 TV Guide 10-14 Cruikshank Lecture 19 We will be closed April 1st Teed Off About the Golf Club 5 TV Guide 10-14 Neufeld Lecture 16 Kids' Corner 22 P2 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 21, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN SEEDY SATURDAY: What to Saturday, March 31 from 9:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Includes lunch, PERCY DE WOLFE MEMORIAL RACE: snacks, and guest speaker John Lenart. Bring seeds for the seed swap! March 22-24. www.thepercy.com AND Call the Rec Dept. for more information on programming, 993-2353. Visit SEE DO www.cityofdawson.ca for a link to sign up for the monthly e-newsletter to or stay current! in DAWSON now: The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to close. MoreThe Downtown live entertainment Hotel in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 p.m. -

Fort Myers to Entice New Business

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Inside today’s SERV ING CA PE CORAL, PINE ISLAND & N. FT. RR MYERS Breeze APE ORAL RR eal E C C MARKETER sta ate Your complete Cape Coral, Lee County G real estate guide orgeo ous T NO w RTH o EDI -S AP TION St RIL 9 tor , 20 ry 09 y C AILY REEZE OVER PRESENTED B D B Y ROSSM See Page AN REALTY 2 WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Partly Cloudy • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 83 Friday, April 10, 2009 50 cents County to use Fort Myers to entice new business Branding scheme raising concern “I’m not happy about it, but you have to follow the data and the facts.” By GRAY ROHRER reasoning behind Lee County bers of the Cape Coral [email protected] Economic Development Director Construction Industry — Cape Coral City Manager Terry Stewart Despite Cape Coral’s greater Jim Moore’s decision to use the Association. numbers in land mass and popula- city across the river to better pro- Some in the audience took tion, Fort Myers is often thought mote the county as a whole as a umbrage at the Cape playing sec- of as its “big” brother. destination for businesses. ond to Fort Myers. eight-year Cape resident. the Cape. As a city, Fort Myers is more “Site selectors know Fort “I have a very difficult time Moore countered that his over- “I’m not going to promote widely known throughout Florida Myers better,” Moore explained understanding the Fort Myers all approach would excite more Cape Coral specifically.