Identity Construction in Colonial Goalpara ( J X Ssj V Oa V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The First Mohammedan Invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa Took

The first Mohammedan invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa took place during the reign of a king called Prithu who was killed in a battle with Illtutmish's son Nassiruddin in 1228. During the second invasion by Ikhtiyaruddin Yuzbak or Tughril Khan, about 1257 AD, the king of Kamrupa Saindhya (1250-1270AD) transferred the capital 'Kamrup Nagar' to Kamatapur in the west. From then onwards, Kamata's ruler was called Kamateshwar. During the last part of 14th century, Arimatta was the ruler of Gaur (the northern region of former Kamatapur) who had his capital at Vaidyagar. And after the invasion of the Mughals in the 15th century many Muslims settled in this State and can be said to be the first Muslim settlers of this region. Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. According to popular Chutia legend, Chutia king Birpal established his rule at Sadia in 1189 AD. He was succeeded by ten kings of whom the eighth king Dhirnarayan or Dharmadhwajpal, in his old age, handed over his kingdom to his son-in-law Nitai or Nityapal. Later on Nityapal's incompetent rule gave a wonderful chance to the Ahom king Suhungmung or Dihingia Raja, who annexed it to the Ahom kingdom.Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Indicators Assam Kokrajhar Dhubri Goalpara

Assam Kokrajhar Dhubri Goalpara Indicators Total Rural Total Rural Total Rural Total Rural Nutritional status below 5 years Below -2 SD Wasting (Weight for Height) (%) Male 20.9 21.5 13.1 12.8 26.5 25.4 - - Female 19.4 19.9 6.0 6.3 22.4 20.6 10.3 9.8 Person 20.2 20.7 9.3 9.2 24.4 23.0 11.3 11.7 Below -3 SD Wasting (Weight for Height) (%) Male 10.2 10.5 9.3 8.8 14.0 14.7 - - Female 8.2 8.2 3.5 3.7 12.4 10.4 6.2 5.7 Person 9.2 9.4 6.2 6.0 13.2 12.5 6.4 6.5 Below -2 SD Stunting (Height for Age) (%) Male 38.4 39.8 35.2 34.0 30.7 32.3 34.4 35.0 Female 36.4 37.9 32.2 30.2 36.7 37.9 27.1 27.6 Person 37.4 38.9 33.5 31.9 33.8 35.2 30.7 31.3 Below -3SD Stunting (Height for Age) (%) Male 18.8 19.5 11.7 10.8 21.5 22.6 21.8 21.9 Female 15.8 16.6 11.0 - 20.3 21.0 - - Person 17.4 18.1 11.3 9.9 20.9 21.8 14.8 14.9 Below -2 SD Underweight (Weight for Age) (%) Male 32.1 34.1 31.0 29.2 35.4 37.1 31.3 31.7 Female 29.3 31.1 18.6 17.9 28.0 28.4 19.5 20.3 Person 30.8 32.6 24.2 23.2 31.6 32.4 25.5 26.1 Below -3 SD Underweight (Weight for Age) (%) Male 11.7 12.6 11.8 10.9 - - 17.6 18.9 Female 10.6 11.5 3.4 3.6 9.2 9.7 12.9 13.6 Person 11.1 12.1 7.2 7.0 9.6 10.3 15.3 16.3 Below -2 SD Undernourished (BMI for Age) (%) Male 23.0 23.3 12.9 12.7 31.6 25.5 21.3 23.3 Female 21.7 22.3 10.0 10.6 24.3 20.5 15.0 15.3 Person 22.3 22.9 11.3 11.5 27.9 22.9 18.1 19.4 Below -3 SD Undernourished (BMI for Age) (%) Male 14.1 14.2 9.1 9.2 18.7 14.3 18.0 19.7 Female 12.2 12.5 4.5 4.8 15.6 11.4 11.0 11.2 Person 13.2 13.4 6.6 6.8 17.1 12.8 14.5 15.5 Above 2 SD Overnourished (BMI for -

Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal Para)

CHAPTER- III Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal para) Erstwhile Goalpara district of Western Assam has a unique socio-cultural heritage of its own, identified as Goalpariya Society and Culture. The society is a heterogenic in character, composed of diverse racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups. The medieval society that had developed in Western Assam, particularly in Goalapra region was seriously influenced by the induction of new social elements during the British Rule. It caused the reshaping of the society to a fully heterogenic in character with distinctly emergence of new cultural heritage, inconsequence of the fusion of the diverse elements. Zamindars of Western Assam, as an important social group, played a very important role in the development of new society and cufture. In the course of their zamindary rule, they brought Bengali Hidus from West Bengal for employment in zamindary service, Muslim agricultural labourers from East Bengal for extension of agricultural field, and other Hindusthani people for the purpose of military and other services. Most of them were allowed to settle in their respective estates, resulting in the increase of the population in their estate as well as in Assam. Besides, most of the zamindars entered in the matrimonial relations with the land lords of Bengal. As a result, we find great influence of the Bengali language and culture on this region. In the subsequent year, Bengali cultivators, business community of Bengal and Punjab and workers and labourers from other parts of Indian subcontinent, migrated in large number to Assam and settled down in different places including town, Bazar and waste land and char areas. -

Bir Chilarai

Bir Chilarai March 1, 2021 In news : Recently, the Prime Minister of India paid tribute to Bir Chilarai(Assam ‘Kite Prince’) on his 512th birth anniversary Bir Chilarai(Shukladhwaja) He was Nara Narayan’s commander-in-chief and got his name Chilarai because, as a general, he executed troop movements that were as fast as a chila (kite/Eagle) The great General of Assam, Chilarai contributed a lot in building the Koch Kingdom strong He was also the younger brother of Nara Narayan, the king of the Kamata Kingdom in the 16th century. He along with his elder brother Malla Dev who later known as Naya Narayan attained knowledge about warfare and they were skilled in this art very well during their childhood. With his bravery and heroism, he played a crucial role in expanding the great empire of his elder brother, Maharaja Nara Narayan. He was the third son of Maharaja Biswa Singha (1523–1554 A.D.) The reign of Maharaja Viswa Singha marked a glorious episode in the history of Assam as he was the founder ruler of the Koch royal dynasty, who established his kingdom in 1515 AD. He had many sons but only four of them were remarkable. With his Royal Patronage Sankardeva was able to establish the Ek Saran Naam Dharma in Assam and bring about his cultural renaissance. Chilaray is said to have never committed brutalities on unarmed common people, and even those kings who surrendered were treated with respect. He also adopted guerrilla warfare successfully, even before Shivaji, the Maharaja of Maratha Empire did. -

Social Novel in Assamese a Brief Study with Jivanor Batot and Mirijiyori

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 06, 2020 SOCIAL NOVEL IN ASSAMESE A BRIEF STUDY WITH JIVANOR BATOT AND MIRIJIYORI Rodali Sopun Borgohain Research Scholar, Gauhati University, Assam, India Abstract : Social novel is a way to tell us about problems of our society and human beings. The social Novel is a ‘Pocket Theater’ who describe us about picture of real lifes. The Novel is a very important thing of educational society. The social Novel is writer basically based on social life. The social Novel “Jivonar Batot and Mirijiyori, both are reflect us about problems of society, thinking of society and the thought of human beings. Introduction : A novel is narrative work and being one of the most powerful froms that emerged in all literatures of the world. Clara Reeve describe the novel as a ‘Picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is writter. A novel which is written basically based on social life, the novel are called social novel. In the social Novels, any section or class of the human beings are dealt with. A novel is a narrative work and being one of the most powerful forms that emerged in all literatures of the world particularly during 19th and 20th centuries, is a literary type of certain lenght that presents a ‘story in fictionalized form’. Marion crawford, a well known American novelist and critic described the novel as a ‘pocket theater’, Clara Reeve described the Novel as a “picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is written”. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

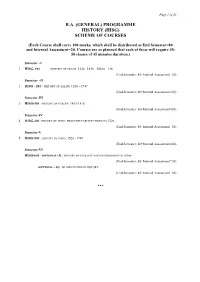

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Radha Govinda Baruah(1900-1977), the Architect of Modern Assam and His Times

International Journal of Management (IJM) Volume 11, Issue 11, November 2020, pp. 1438-1443. Article ID: IJM_11_11_136 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=11 Journal Impact Factor (2020): 10.1471 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.11.2020.136 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed RADHA GOVINDA BARUAH(1900-1977), THE ARCHITECT OF MODERN ASSAM AND HIS TIMES Jyotishman Das Department of Assamese, Tezpur University, Napam, 784028, India ABSTRACT The nineteenth century is a very significant period in the history of Assam. At that time a new era started in Assam in the light of colonial modernity. Radha Gobinda Boruah is one of the well known figures born in the last year of this 19 th century who set up a new momentum to the economic, cultural, educational and social renaissance that emerged in the 19th century Assam in the hand of intelligentsia formed by literate middle class of contemporary Assam. He played a pioneering role in almost every sphere of public life of mid 20 th century Assam. He was the founder of the Assam Tribune Group, he brought ‘bihu’(festival of Assam) onto stage from the fields, and initiated a number of other cultural and sports activities. That’s why he is called ‘the architect of modern Assam’. The objective of this research paper is to discuss his contribution in modernization of 20th century Assam. The nature of modernity in Assam during that period will also be highlighted. Key words: Assam, Economy, Modernization, Radha Govinda Barua, Twentieth century. -

Tribal Religion of Lower Assam of North East India

TRIBAL RELIGION OF LOWER ASSAM OF NORTH EAST INDIA 1HEMANTA KUMAR KALITA, 2BHANU BEZBORA KALITA 1Associate Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, Goalpara College, 2Associate Professor, Dept of Assamese, Goalpara College E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Religion is very sensitive issue and naturally concerned with the sentiment. It is a matter of faith and made neither through logical explanation nor scientific verification. That Religion from its original point of view was emerged as the basic needs and tools of livelihood. Hence it was the creation of human being feeling wonderful happenings bosom of nature at the early stage of origin of religion. It is not exaggeration that tribal people are the primitive bearer of religious belief. However religion for them was not academically explored rather it was regarded as the matter of reverence and submission. If we regard religion from the original point of view the religion then is not discussed under the caprice of ill design.. To think about God, usually provides no scientific value as it is not a matter of verification and material pleasant. Although to think about God or pray to God is also not worthless. Pessimistic and atheistic ideology though not harmful to human society yet the reverence and faith towards God also minimize the inter religious hazards and conflict. It may help to strengthen spirituality and communicability with others. Spiritualism renders a social responsibility in true sense which helps to understand others from inner order of heart. We attempt to discuss some tribal religious festivals along with its special characteristics. Tribal religion though apart from the general characteristic feature it ushers natural gesture and caries tolerance among them. -

1Edieval Assam

.-.':'-, CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION : Historical Background of ~1edieval Assam. (1) Political Conditions of Assam in the fir~t half of the thirt- eenth Century : During the early part of the thirteenth Century Kamrup was a big and flourishing kingdom'w.ith Kamrupnagar in the· North Guwahat.i as the Capital. 1 This kingdom fell due to repeated f'.1uslim invasions and Consequent! y forces of political destabili t.y set in. In the first decade of the thirteenth century Munammedan 2 intrusions began. 11 The expedition of --1205-06 A.D. under Muhammad Bin-Bukhtiyar proved a disastrous failure. Kamrtipa rose to the occasion and dealt a heavy blow to the I"'!Uslim expeditionary force. In 1227 A.D. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz entered the Brahmaputra valley to meet with similar reverse and had to hurry back to Gaur. Nasiruddin is said to have over-thrown the I<~rupa King, placed a successor to the throne on promise of an annual tribute. and retired from Kamrupa". 3 During the middle of the thirteenth century the prosperous Kamrup kingdom broke up into Kamata Kingdom, Kachari 1. (a) Choudhury,P.C.,The History of Civilisation of the people of-Assam to the twelfth Cen tury A.D.,Third Ed.,Guwahati,1987,ppe244-45. (b) Barua, K. L. ,·Early History of :Kama r;upa, Second Ed.,Guwahati, 1966, p.127 2. Ibid. p. 135. 3. l3asu, U.K.,Assam in the l\hom J:... ge, Calcutta, 1 1970, p.12. ··,· ·..... ·. '.' ' ,- l '' '.· 2 Kingdom., Ahom Kingdom., J:ayantiya kingdom and the chutiya kingdom. TheAhom, Kachari and Jayantiya kingdoms continued to exist till ' ' the British annexation: but the kingdoms of Kamata and Chutiya came to decay by- the turn of the sixteenth century~ · .