A Howling Wilderness: Stagecoach Days in the Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Early Land-Use on Streams of the Santa Cruz Mountains: Implications for Coho Salmon Recovery

Impacts of early land-use on streams of the Santa Cruz Mountains: implications for coho salmon recovery San Lorenzo Valley Museum collection Talk Outline • Role of San Lorenzo River in coho salmon recovery • History of 19th century land-use practices • How these disturbances impacted (and still impact) ecosystem function and salmon habitat Central California Coast ESU Lost Coast – Navarro Pt. Coho salmon Diversity Strata Navarro Pt. – Gualala Pt. Coastal San Francisco Bay Santa Cruz Mountains Watersheds with historical records of Coho Salmon Dependent populations Tunitas Independent populations San Gregorio Pescadero Gazos Waddell Scott San Vicente Laguna Soquel San Lorenzo Aptos Land-use activities: 1800-1905 Logging: the early years • Pit and whipsaw era (pre-1842) – spatially limited, low demand – impacts relatively minor • Water-powered mills (1842-1875) – Demand fueled by Gold Rush – Mills cut ~5,000 board ft per day = 10 whip sawyers – Annual cut 1860 = ~10 million board ft • Steam-powered mills (1876-1905) – Circular saws doubled rate to ~10,000 board ft/day x 3-10 saws – Year-round operation (not dependent on water) – Annual cut 1884 = ~34 million board ft – Exhausted timber supply Oxen team skidding log on corduroy road (Mendocino Co. ca 1851) Krisweb.com Oxen team hauling lumber at Oil Creek Mill San Lorenzo Valley Museum collection oldoregonphotos.com San Vicente Lumber Company (ca 1908): steam donkey & rail line Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History Loma Prieta Mill, Mill Pond, and Rail Line (ca 1888) Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History The Saw-Dust Nuisance “We have always maintained that lumberman dumping their refuse timber and saw-dust into the San Lorenzo River and its tributaries were committing a nuisance. -

Stagecoach Trail (#36 on the ASRA Topo Trail Map)

Stagecoach Trail (#36 on the ASRA Topo Trail Map) Distance: 2 miles; 1½ hrs. up, ¾ hrs down “Stagecoach Trail to Russell Road” sign. The (hiking) first ¼ mile is the steepest, but it provides good views of the North Fork American River, at Difficulty: Moderate up, easy down several spots on the right. Slope: 8% avg; 23% max. (see below) At about ¼ mile, the trail turns sharply left at the “Stagecoach Trail” sign. As you pause to catch your breath, you can almost hear the echo of Trailhead / Parking: (N38-55-010; W121-02-207) harness bells on horses and the clatter of stage- Trailhead is at confluence area, 1¾ miles south coaches that once traveled this road. of ASRA Park Headquarters. Take Hwy 49 from A short distance up the trail, the graceful arches Auburn south to Old Foresthill Road at the bottom of Mt. Quarries RR Bridge come into view on the of the canyon. Continue straight for ¼ mile and left. A little further along, the appearance of park on the left. Trailhead is just beyond parking ponderosa pine, big leaf maple, interior live oak, area at green gate near kiosk and port-a-potty. blue oak, willow, and Himalayan blackberry bushes signal the first of several riparian Description corridors on the trail. Here you can see water This historic trail offers great, bird’s eye views of running year round, unlike other spots on the the confluence area and American River canyon. trail where it is only visible in winter and spring. Its gradual gradient offers a good aerobic workout A little further on, a narrow unmarked trail known on the way up, climbing 800 ft in 2 miles from the as Tinker’s Cut-off intersects on the left. -

Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University GSP Projects Student and Alumni Works Fall 12-2020 Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains Sarah Christine Brewer Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/gspproject Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Brewer, Sarah Christine, "Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains" (2020). GSP Projects. 1. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/gspproject/1 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student and Alumni Works at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in GSP Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains GSP 510 Final Project BY: SARAH BREWER DECEMBER 2020 Abstract This project identifies areas of archaeological sensitivity for historic resources related to the segment of the South Pacific Coast Railroad that spanned from Los Gatos to Glenwood in the steep terrain of the Santa Cruz Mountains in Central California. The rail line was only in use for 60 years (1880-1940) until the completion of a major highway drew travelers to greater automobile use. During the construction and operation of the rail line, small towns sprouted at the railroad stops, most of which were abandoned along with the rail line in 1940. Some of these towns are now inundated by reservoirs. This project maps the abandoned rail line and “ghost towns” by using ArcGIS Pro (version 2.5.1) to digitize the railway, wagon roads, and structures shown on a georeferenced topographic quadrangle created in 1919 (Marshall et al., 1919). -

Conifer Communities of the Santa Cruz Mountains and Interpretive

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA CONIFERS: CONIFER COMMUNITIES OF THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS AND INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE FOR THE UCSC ARBORETUM AND BOTANIC GARDEN A senior internship project in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES by Erika Lougee December 2019 ADVISOR(S): Karen Holl, Environmental Studies; Brett Hall, UCSC Arboretum ABSTRACT: There are 52 species of conifers native to the state of California, 14 of which are endemic to the state, far more than any other state or region of its size. There are eight species of coniferous trees native to the Santa Cruz Mountains, but most people can only name a few. For my senior internship I made a set of ten interpretive signs to be installed in front of California native conifers at the UCSC Arboretum and wrote an associated paper describing the coniferous forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Signs were made using the Arboretum’s laser engraver and contain identification and collection information, habitat, associated species, where to see local stands, and a fun fact or two. While the physical signs remain a more accessible, kid-friendly format, the paper, which will be available on the Arboretum website, will be more scientific with more detailed information. The paper will summarize information on each of the eight conifers native to the Santa Cruz Mountains including localized range, ecology, associated species, and topics pertaining to the species in current literature. KEYWORDS: Santa Cruz, California native plants, plant communities, vegetation types, conifers, gymnosperms, environmental interpretation, UCSC Arboretum and Botanic Garden I claim the copyright to this document but give permission for the Environmental Studies department at UCSC to share it with the UCSC community. -

Preliminary Isoseismal Map for the Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta), California, Earthquake of October 18,1989 UTC

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Preliminary isoseismal map for the Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta), California, earthquake of October 18,1989 UTC Open-File Report 90-18 by Carl W. Stover, B. Glen Reagor, Francis W. Baldwin, and Lindie R. Brewer National Earthquake Information Center U.S. Geological Survey Denver, Colorado This report has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial stan dards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Introduction The Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta) earthquake, occurred on October 18, 1989 UTC (October 17, 1989 PST). This major earthquake was felt over a contiguous land area of approximately 170,000 km2; this includes most of central California and a portion of western Nevada (fig. 1). The hypocen- ter parameters computed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) are: Origin time: 00 04 15.2 UTC Location: 37.036°N., 121.883°W. Depth: 19km Magnitude: 6.6mb,7.1Ms. The University of California, Berkeley assigned the earthquake a local magnitude of 7.0ML. The earthquake caused at least 62 deaths, 3,757 injuries, and over $6 billion in property damage (Plafker and Galloway, 1989). The earthquake was the most damaging in the San Francisco Bay area since April 18,1906. A major arterial traffic link, the double-decked San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, was closed because a single fifty foot span of the upper deck collapsed onto the lower deck. In addition, the approaches to the bridge were damaged in Oakland and in San Francisco. Other se vere earthquake damage was mapped at San Francisco, Oakland, Los Gatos, Santa Cruz, Hollister, Watsonville, Moss Landing, and in the smaller communities in the Santa Cruz Mountains. -

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. M A Y - 2 0 1 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................1 Purpose.................................................................................................................................2 Background & Collaboration...............................................................................................3 The Landscape .....................................................................................................................6 The Wildfire Problem ..........................................................................................................8 Fire History Map................................................................................................................10 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................11 Reducing Structural Ignitability.........................................................................................12 x Construction Methods............................................................................................13 x Education ...............................................................................................................15 -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared By

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. APRIL - 2 0 1 8 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 3 Background & Collaboration ............................................................................................... 4 The Landscape .................................................................................................................... 7 The Wildfire Problem ........................................................................................................10 Fire History Map ............................................................................................................... 13 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................14 Reducing Structural Ignitability .........................................................................................16 • Construction Methods ........................................................................................... 17 • Education ............................................................................................................. -

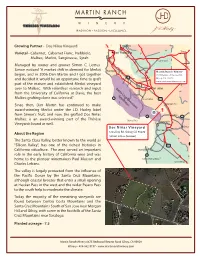

Dos Niñas Vineyard Berkeley

Growing Partner - Dos Niñas Vineyard Berkeley Tracy Varietal - Cabernet, Cabernet Franc, Nebbiolo, San Francisco Malbec, Merlot, Sangiovese, Syrah Livermore Managed by owner and grower Simon C. Lemus. Simon noticed "A market shift in demand for Merlot San Mateo Martin Ranch Winery began, and in 2006 Dan Martin and I got together 6675 Redwood Retreat Rd, and decided it would be an opportune time to graft 92 Gilroy, CA 95020 www.martinranchwinery.com part of the mature and established Merlot vineyard over to Malbec. With relentless research and input Santa Cruz Mountains San Jose from the University of California at Davis, the best Appellation Malbec grafting clone was selected." 1 Los Gatos 101 Since then, Dan Martin has continued to make Morgan Hill award-winning Merlot under the J.D. Hurley label from Simon's fruit, and now, the grafted Dos Niñas Gilroy 1 152 Malbec is an award-winning part of the Thérèse Santa Cruz Watsonville Vineyards brand as well. Dos Niñas Vineyard Hollister San Juan Bautista About the Region 1225 Day Rd, Gilroy, CA 95020 Simon Limas (Grower) The Santa Clara Valley, better known to the world as "Silicon Valley", has one of the richest histories in 101 California viticulture. The area served an important Monterey role in the early history of California wine and was 1 home to the pioneer winemakers Paul Masson and Carmel Valley Village Charles Lefranc. Greenfield The valley is largely protected from the inuence of the Pacic Ocean by the Santa Cruz Mountains, although coastal breezes that enter a small opening at Hecker Pass in the west and the wider Pajaro Pass to the south help to moderate the climate. -

<B>FREDERICK (FRED) J. FRAIKOR.</B> Born 1937. <B

<b>FREDERICK (FRED) J. FRAIKOR.</b> Born 1937. <b>Transcript</b> of <b>OH 1359V A-B</b> This interview was recorded on June 16, 2005, for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program and the Rocky Flats Cold War Museum. The interviewer is Hannah Nordhaus. The interview is also available in video format, filmed by Hannah Nordhaus. The interview was transcribed by Sandy Adler. NOTE: Interviewer’s questions and comments appear in parentheses. Added material appears in brackets. [A]. 00:00 (OK, we’re recording. This is the Rocky Flats Cold War Museum Oral History Project. I’m interviewing Fred Fraikor. I’m Hannah Nordhaus. It’s the 16th of June, 2005. We’re at Fred’s office at the Colorado School of Mines, where he teaches.) (Fred, to get started, if you could just tell me a little bit about your background, where you were born, what your parents did.) OK. I was born in a steel town called Ducaine, Pennsylvania, which is one of the suburbs of Pittsburgh. My parents, although my dad grew up here, were of Slovak—back then it was Czechoslovakia—origin. My dad, like all the other immigrants at the time, would run back and forth, they’d make their money in the coal mines and the steel mills and then they’d go back to Czechoslovakia, buy up land, and come back here. What they didn’t realize was that the Communists would then confiscate the land, which is why I’m not a big land baron at this point. He brought my mother back here in 1936, just before World War II, when the Nazis invaded. -

Review of Death of a Gunfighter: the Quest for Jack Slade, the West's Most Elusive Legend by Dan Rottenberg J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2010 Review of Death of a Gunfighter: The Quest for Jack Slade, the West's Most Elusive Legend By Dan Rottenberg J. Randolph Cox Dundas, Minnesota Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Cox, J. Randolph, "Review of Death of a Gunfighter: The Quest for Jack Slade, the West's Most Elusive Legend By Dan Rottenberg" (2010). Great Plains Quarterly. 2531. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2531 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 56 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, WINTER 2010 Death of a Gunfighter: The Quest for Jack Slade, the West's Most Elusive Legend. By Dan Rottenberg. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2008. xiv + 520 pp. Maps, photographs, notes, bibliogra phy, index. $29.95. Freight teamster and wagon master along the Overland Trail, stagecoach driver in Texas, as well as stagecoach division superintendent along the Central Overland route, Joseph Alfred "Jack" Slade (1831-1864) is remembered for having helped launch and operate the Pony Express in 1860-61. He is also remembered as a gunfighter and the "Law West of Kearney." The BOOK REVIEWS 57 legends about him (including those in Mark Twain's Roughing It and Prentiss Ingraham's dime novels about Buffalo Bill) are largely false, but the truth has been difficult to establish. -

Hidalgo County Historical Museum Archives

Museum of South Texas History Archives Photo Collection Subject Index Inventory Headings List Revision: January 2016 Consult archivist for finding aids relating to photo collections, negatives, slides, stereographs, or exhibit images. HEADING KEY I. Places II. People III. Activity IV. Things The HEADING lists are normally referred to only by their Roman numeral. For example, II includes groups and organizations, and III includes events and occupations. Each of the four HEADING lists is in upper case arranged alphabetically. Occasionally, subheadings appear as italics or with underlining, such as I GOVT BUILDINGS Federal Linn Post Office. Infrequently sub- subheading may appear, indicated by another right margin shift. Beneath each HEADING, Subheading, or Sub-subheading are folder titles. KEY HEADINGS = All Caps Subheadings= Underlined Folder Title = Regular Capitalization A I. AERIAL Brownsville/Matamoros Edinburg/Pan American/HCHM Elsa/Edcouch Hidalgo La Blanca Linn McAllen Madero McAllen Mission/Sharyland Mexico Padre Island, South/Port Isabel Pharr Rio Grande City/Fort Ringgold San Antonio Weslaco I. AGRICULTURE/SUPPLIES/BUSINESSES/AGENCIES/SEED and FEED I. AIRBASES/AIRFIELDS/AIRPORTS Brownsville Harlingen McAllen (Miller) Mercedes Moore World War II Korea Screwworm/Agriculture/Medical Science Projects Reynosa San Benito I. ARCHEOLOGY SITES Boca Chica Shipwreck Mexico I. AUCTION HOUSES B I. BACKYARDS I. BAKERIES/ PANADERIAS I. BANDSTANDS/QIOSCOS/KIOSKS/PAVILIONS Edinburg Mexico Rio Grande City 2 I. BANKS/SAVINGS AND LOANS/CREDIT UNIONS/INSURANCE AGENCIES/ LOAN COMPANY Brownsville Edinburg Chapin Edinburg State First National First State (NBC) Groundbreaking Construction/Expansion Completion Openings Exterior Interior Elsa Harlingen Hidalgo City La Feria McAllen First National Bank First State McAllen State Texas Commerce Mercedes Mission Monterrey San Antonio San Benito San Juan I. -

Unit Strategic Fire Plan San Mateo

Unit Strategic Fire Plan San Mateo - Santa Cruz Cloverdale VMP - 2010 6/15/2011 Table of Contents SIGNATURE PAGE ................................................................................................................................ 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 3 SECTION I: UNIT OVERVIEW UNIT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................. 4 UNIT PREPAREDNESS AND FIREFIGHTING CAPABILITIES................................................. 8 SECTION II: COLLABORATION DEVELOPMENT TEAM ........................................................................................................... 12 SECTION III: VALUES AT RISK IDENTIFICATION OF ASSETS AT RISK ................................................................................ 15 COMMUNITIES AT RISK ........................................................................................................ 17 SECTION IV: PRE FIRE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FIRE PREVENTION ................................................................................................................. 18 ENGINEERING & STRUCTURE IGNITABILITY ............................................................... 19 INFORMATION AND EDUCATION .................................................................................. 22 VEGETATION MANAGEMENT .............................................................................................