Preserved Brain of the Woolly Mammoth (Mammuthus Primigenius (Blumenbach 1799)) from the Yakutian Permafrost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mg2sio4) in a H2O-H2 Gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S

Goldschmidt2013 Conference Abstracts 2297 Compacted Nanoparticles for Evaporation behavior of forsterite Quantification in LA-ICPMS (Mg2SiO4) in a H2O-H2 gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S. TACHIBANA1* AND A. TAKIGAWA2 2 2 1 , HALIM , MICHAEL ROSSIER AND DETLEF GÜNTHER * 1 Department of Natural History Sciences, Hokkaido 1ETH Zurich, Department of Chemistry and Applied University, N10 W8, Sapporo 060-0810, Japan. Biosciences, Laboratory of Inorganic Chemistry (*correspondence: [email protected]) (*correspondence: [email protected]) 2Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial 2Nanograde, Staefa, Switzerland Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington DC, 20015 USA. Gray et al. did first studies of LA-ICPMS in 1985 [1]. Ever since, extensive research has been performed to Forsterite (Mg2SiO4) is one of the most abundant overcome the problem of so-called “non-stoichiometric crystalline silicates in extraterrestrial materials and in sampling” and/or analysis, the origins of which are commonly circumstellar environments, and its evaporation behavior has referred to as elemental fractionation (EF). EF mainly consists been intensively studied in vacuum and in the presence of of laser-, transport- and ICP-induced effects, and often results low-pressure hydrogen gas [e.g., 1-4]. It has been known that in inaccurate analyses as pointed out in, e.g. references [2,3]. the evaporation rate of forsterite is controlled by a A major problem that has to be addressed is the lack of thermodynamic driving force (i.e., equilibrium vapor reference materials. Though the glass series of NIST SRM 61x pressure), and the evaporation rate increases linearly with 1/2 have been the most commonly reference material used in LA- pH2 in the presence of hydrogen gas due to the increase of ICPMS, heterogeneities have been reported for some sample the equilibrium vapor pressure. -

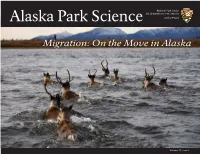

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Signs of Biological Activities of 28,000-Year-Old Mammoth Nuclei in Mouse Oocytes Visualized by Live-Cell Imaging

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Signs of biological activities of 28,000-year-old mammoth nuclei in mouse oocytes visualized by Received: 12 October 2018 Accepted: 19 February 2019 live-cell imaging Published: xx xx xxxx Kazuo Yamagata1, Kouhei Nagai1, Hiroshi Miyamoto1, Masayuki Anzai2, Hiromi Kato2, Kei Miyamoto1, Satoshi Kurosaka2, Rika Azuma1, Igor I. Kolodeznikov3, Albert V. Protopopov3, Valerii V. Plotnikov3, Hisato Kobayashi 4, Ryouka Kawahara-Miki 4, Tomohiro Kono4,5, Masao Uchida6, Yasuyuki Shibata6, Tetsuya Handa7, Hiroshi Kimura7, Yoshihiko Hosoi1, Tasuku Mitani1, Kazuya Matsumoto1 & Akira Iritani2 The 28,000-year-old remains of a woolly mammoth, named ‘Yuka’, were found in Siberian permafrost. Here we recovered the less-damaged nucleus-like structures from the remains and visualised their dynamics in living mouse oocytes after nuclear transfer. Proteomic analyses demonstrated the presence of nuclear components in the remains. Nucleus-like structures found in the tissue homogenate were histone- and lamin-positive by immunostaining. In the reconstructed oocytes, the mammoth nuclei showed the spindle assembly, histone incorporation and partial nuclear formation; however, the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confrmed. DNA damage levels, which varied among the nuclei, were comparable to those of frozen-thawed mouse sperm and were reduced in some reconstructed oocytes. Our work provides a platform to evaluate the biological activities of nuclei in extinct animal species. Ancient species carry invaluable information about the genetic basis of adaptive evolution and factors related to extinction. Fundamental studies on woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) genes, including whole genome analyses1–3, led to the reconstitution of mammoth haemoglobin with cold tolerance4 and to an understanding of the expression of mammoth-specifc coat colour5 and temperature-sensitive channels6. -

Ground-Ice Stable Isotopes and Cryostratigraphy Reflect Late

Clim. Past, 13, 587–611, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-587-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Ground-ice stable isotopes and cryostratigraphy reflect late Quaternary palaeoclimate in the Northeast Siberian Arctic (Oyogos Yar coast, Dmitry Laptev Strait) Thomas Opel1,a, Sebastian Wetterich1, Hanno Meyer1, Alexander Y. Dereviagin2, Margret C. Fuchs3, and Lutz Schirrmeister1 1Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Periglacial Research Section, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 2Geology Department, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 119992, Russia 3Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, Helmholtz Institute Freiberg for Resource Technology, 09599 Freiberg, Germany anow at: Department of Geography, Permafrost Laboratory, University of Sussex, Brighton, BN1 9RH, UK Correspondence to: Thomas Opel ([email protected], [email protected]) Received: 3 January 2017 – Discussion started: 9 January 2017 Accepted: 4 May 2017 – Published: 6 June 2017 Abstract. To reconstruct palaeoclimate and palaeoenvi- ago, and extremely cold winter temperatures during the Last ronmental conditions in the northeast Siberian Arctic, we Glacial Maximum (MIS2). Much warmer winter conditions studied late Quaternary permafrost at the Oyogos Yar are reflected by extensive thermokarst development during coast (Dmitry Laptev Strait). New infrared-stimulated lu- MIS5c and by Holocene ice-wedge stable isotopes. Modern minescence ages for distinctive floodplain deposits of the ice-wedge -

Architectonics of the Hairs of the Woolly Mammoth and Woolly Rhino O.F

Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS Vol. 319, No. 3, 2015, рр. 441–460 УДК 591.478 ARCHITECTONICS OF THE HAIRS OF THE WOOLLY MAMMOTH AND WOOLLY RHINO O.F. Chernova1*, I.V. Kirillova2, G.G. Boeskorov3, F.K. Shidlovskiy2 and M.R. Kabilov4 1A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskiy Pr. 33, 119071 Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 2“National Alliance of Shidlovskiy”. “Ice Age”, Ice Age Museum, 129223 Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 3The Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Lenina Pr. 39, 677890 Yakutsk, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 4Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Academika Lavrent’eva Pr. 8, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia ABSTRACT SEM studies of hairs of two individuals of the woolly rhinoceros (rhino) Coelodonta antiquitatis and six individuals of the woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius, and hairs of matted wool (“wads”) of a possible woolly mammoth and/or woolly rhinoceros (X-probe) showed that coloration and differentiation of the hair, hair shaft shape, cuticle ornament and cortical structure are similar in both species and in the X-probe. The cortex has numerous longitu- dinal slits, which some authors misinterpret as medullae. In both species, the medulla is degenerative and does not affect the insulation properties of the hairs. Nevertheless its architectonics, occasionally discernible in thick hairs, is a major diagnostic for identification of these species. The hair structure of rhino is similar to that of the vibrissae of some predatory small mammals and suggests increased resilience. -

Ice Age Megafauna and Time Notes Contents

Ice Age megafauna and time notes Contents 1 Ice age 1 1.1 Origin of ice age theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Evidence for ice ages ......................................... 2 1.3 Major ice ages ............................................ 3 1.4 Glacials and interglacials ....................................... 4 1.5 Positive and negative feedback in glacial periods ........................... 5 1.5.1 Positive feedback processes ................................. 5 1.5.2 Negative feedback processes ................................. 5 1.6 Causes of ice ages ........................................... 5 1.6.1 Changes in Earth’s atmosphere ................................ 6 1.6.2 Position of the continents ................................... 6 1.6.3 Fluctuations in ocean currents ................................ 7 1.6.4 Uplift of the Tibetan plateau and surrounding mountain areas above the snowline ...... 7 1.6.5 Variations in Earth’s orbit (Milankovitch cycles) ....................... 7 1.6.6 Variations in the Sun’s energy output ............................. 8 1.6.7 Volcanism .......................................... 8 1.7 Recent glacial and interglacial phases ................................. 8 1.7.1 Glacial stages in North America ............................... 8 1.7.2 Last Glacial Period in the semiarid Andes around Aconcagua and Tupungato ........ 9 1.8 Effects of glaciation .......................................... 9 1.9 See also ................................................ 10 1.10 References ............................................. -

Architectonics of the Hairs of the Woolly Mammoth and Woolly Rhino O.F

Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS Vol. 319, No. 3, 2015, рр. 441–460 УДК 591.478 ARCHITECTONICS OF THE HAIRS OF THE WOOLLY MAMMOTH AND WOOLLY RHINO O.F. Chernova1*, I.V. Kirillova2, G.G. Boeskorov3, F.K. Shidlovskiy2 and M.R. Kabilov4 1A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskiy Pr. 33, 119071 Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 2“National Alliance of Shidlovskiy”. “Ice Age”, Ice Age Museum, 129223 Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 3The Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Lenina Pr. 39, 677890 Yakutsk, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 4Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Academika Lavrent’eva Pr. 8, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia ABSTRACT SEM studies of hairs of two individuals of the woolly rhinoceros (rhino) Coelodonta antiquitatis and six individuals of the woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius, and hairs of matted wool (“wads”) of a possible woolly mammoth and/or woolly rhinoceros (X-probe) showed that coloration and differentiation of the hair, hair shaft shape, cuticle ornament and cortical structure are similar in both species and in the X-probe. The cortex has numerous longitu- dinal slits, which some authors misinterpret as medullae. In both species, the medulla is degenerative and does not affect the insulation properties of the hairs. Nevertheless its architectonics, occasionally discernible in thick hairs, is a major diagnostic for identification of these species. The hair structure of rhino is similar to that of the vibrissae of some predatory small mammals and suggests increased resilience. -

Morphological and Molecular Approaches to Characterise Modifications Relating to Mammalian Hairs in Archaeological, Paleontological and Forensic Contexts

MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR APPROACHES TO CHARACTERISE MODIFICATIONS RELATING TO MAMMALIAN HAIRS IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL, PALEONTOLOGICAL AND FORENSIC CONTEXTS Silvana Rose Tridico BSc (Hons) in Applied Biology (University of Hertford, UK) THIS THESIS IS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES MURDOCH UNIVERSITY School of Veterinary and Life Sciences 2015 DECLARATION I declare that this is my own account of my research and contains, as its main content, work that has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Silvana R. Tridico ii ABSTRACT Mammalian hair is readily shed and transferred to persons or objects during contact; this property renders hair as one of the most ubiquitous and prevalent evidence type encountered in forensic investigations and at ancient burial sites. The durability and stability of hair ensures their survival for millennia; their status as a privileged repository of viable genetic material consolidates their value as a biological substrate. The aims of this thesis are to showcase the wealth, and breadth, of information that may be gleaned from these unique structures and address the current problem regarding the mis-identification of animal hairs. Despite the similar appearance of human and animal hairs, the expertise required to accurately interpret their respective structures requires significantly different skill sets. Chapter Two in this thesis discusses the consequences of mis-identification of hair structures due to lack of competency or adequate training in regards to hair examiners and discusses some of the myths and misconceptions associated with microscopy of hairs. Hairs are resilient structures capable of surviving for millennia as exemplified by extinct megafauna hairs; however, they are not totally immune to deleterious effects of environmental insults or biodegradation. -

Vilniaus Mamuto Pėdsakais: Į Pagalbą Mokytojui Neformaliam Gamtamoksliniam Ugdymui Nuotoliniu Būdu

GAMTAMOKSLINIS UGDYMAS BENDROJO UGDYMO MOKYKLOJE – 2020 / NATURAL SCIENCE EDUCATION IN A COMPREHENSIVE SCHOOL – 2020 ISSN 2335-8408 VILNIAUS MAMUTO PĖDSAKAIS: Į PAGALBĄ MOKYTOJUI NEFORMALIAM GAMTAMOKSLINIAM UGDYMUI NUOTOLINIU BŪDU Eugenija Rudnickaitė Vilniaus universitetas, Lietuva El. paštas: [email protected] Įvadas Pasaulyje dėl COVID-19 viruso siautėjimo bangomis, primenančiomis audringą vandenyną, susidarius neapibrėžtai bendrojo ugdymo situacijai mokyklose, ypač komplikuotu tampa neformalusis gamtamokslinis ugdymas. Mokslo festivalio „Erdvėlaivis Žemė“ projekto organizatorių, dalį savo renginių iš anksto planavusių virtualioje erdvėje, dėka galime neformaliam gamtamoksliniam ugdymui mokytojams pasiūlyti virtualią ekskursiją į Vilniaus universiteto Geologijos muziejaus laikiną parodą. Tikimės patarti mokytojams, kaip šią virtualią išvyką panaudoti norimų gebėjimų išugdymui. Šio straipsnio tikslas: ● parodyti kaip neformalaus gamtamokslinio ugdymo išvykas galima panaudoti pamokose gautų žinių įtvirtinimui; ● kaip ugdyti gebėjimus išgirsti reikiamą ir svarbią informaciją; ● kaip šios virtualios išvykos metu sužinotą informaciją panaudoti integruojant į biologijos, gamtos ir žmogaus, chemijos, pasaulio pažinimo, geografijos ir kitus dalykus. Apie VU Geologijos muziejaus, kaip neformalaus gamtamokslinio ugdymo materialinės bazės, galimybes, grindžiamas turimomis turtingomis paleontologinėmis, petrologinėmis, mineralų, meteoritų, regioninės geologijos kolekcijomis, esame ne kartą rašę. Dalijomės ir naujų veiklos formų paieškų -

A Palaeobotanical Approach

Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 214 (2015) 1–8 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/revpalbo Landscapes of the ‘Yuka’ mammoth habitat: A palaeobotanical approach Natalia Rudaya a,d,⁎, Albert Protopopov b, Svetlana Trofimova c, Valery Plotnikov b,SnezhanaZhilicha a Centre of Cenozoic Geochronology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia b Division for Study of the Mammoth Fauna, Sakha Academy of Sciences (Yakutia), Yakutsk 677007, Russia c Laboratory of Palaeoecology, Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology, Yekaterinburg 620144, Russia d Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia article info abstract Article history: In August 2010, a well-preserved Mammuthus primigenius carcass was found along the coast of Oyogos Yar in the Received 6 June 2013 region of the Laptev Sea and the mummy was nicknamed ‘Yuka’. Frozen sediment samples from the area of skull Received in revised form 27 January 2014 condyles were collected for pollen and plant macrofossil analyses. The results from the palaeobotanical investi- Accepted 14 December 2014 gation confirmed that the Yuka mammoth lived during the optimum of the Kargin Interstadial (MIS3). The burial Available online 20 December 2014 place of the mammoth could have been a small shallow freshwater pond with either stagnant or slowly moving water. The vegetation of the Oyogos Yar in MIS3 optimum was probably represented by zonal tundra-steppe Keywords: Yuka mammoth combined with mesic-xeric meadows. Pollen © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Plant macrofossils MIS3 optimum Eastern Siberian Arctic Tundra-steppe 1. Introduction the late Pleistocene and is widespread in West Beringia (Schirrmeister et al., 2013 and references therein). -

Obituaries Yakutian Paleontologist Dr

SVP - Obituaries Yakutian Paleontologist Dr. Piotr Lazarev Passes Away at Age 74 By Olga Potapova, Gennady Boeskorov, Albert Protopopov, Daniel Fisher, and Eugene Maschenko Dr. Piotr Alexeievich Lazarev, Director of the Mammoth Museum in Yakutsk, Yakutia, Russia, passed away on October 23 at the age of 75. Piotr was known to Russian paleontologists as a student and follower of Dr. Prof. Nikolai Vereshchagin. Piotr was born March 18, 1936 in the Yuner Olokh village of the Namskii District of Yakutia. After graduating from high school, he enrolled in Moscow State University, later selecting the Geography Department for his MS degree. Starting in 1959, he worked at the Laboratory of Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology within the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Geology in Yakutsk, where he focused on studies of Pleistocene fauna. As a PhD student of Prof. Nikolai Vereschagin, Dr. Piotr Lazarev studied the Pleistocene horses of Yakutia and in 1974 defended his dissertation. Later, a thorough study of the frozen carcass of the Selerikan horse allowed Dr. Lazarev and Prof. Vereschagin to recognize the Pleistocene horse Equus caballus lenensis Russanov as a separate species, E. lenensis, which was subsequently discovered in vast regions of northern Siberia (Vereschagin & Lazarev, 1977). In 2005 Dr. Piotr Lazarev defended his doctoral (second degree) dissertation “Large Mammals in the Anthropogene of Yakutia”. His knowledge and leadership allowed him to organize a scientific group devoted to studies of the rich Pleistocene deposits in Yakutia and make a significant paleontological collection of mammals. This collection (which comprises now over 7,000 specimens) was incorporated by him into the “Archeo-Paleontological Collection Museum of Northeast Asia” in Yakutsk, which was opened for the 1982 INQUA Annual Meeting. -

Xpedition TAYMY Tion KOLYMA 1995 of the Ushchino Olshiyanov and Ans

erman Cooperation: xpedition TAYMY tion KOLYMA 1995 of the ushchino olshiyanov and ans-W Hubberten with contributions of the participants Ber. Polarforsch, 21 1 (1996) ISSN 0176 - 5027 CONTENTS The Expedition Taymyr 1995. by D.Yu. Bolshianov and H.-W. Hubberten 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................... 2 SUMMARY AND EXPEDITION ITINERARY.......................... 2.1 Time frame. regions and scope of work ................................. 2.2 Transport and radio communication....................................... 2.3 Nature protection measures..................................................... 3 PALEOGEOGRAPHICAL AND GEOMORPHICAL STUDIES .................................................................................... 3.1 The relief and quaternary deposits of the Verkhnyaya Taymyra - Logata area .............................................................. 3.2 Levinson Lessing Lake area .................................................... 4 GEOCRYOLOGICAL AND PALEOGEOGRAPHICAL STUDIES IN THE LABAZ LAKE AREA .................................. 4.1 Introduction ................................................................................ 4.2 Paleogeographical studies On permafrost sequences ....... 4.3 Climatic influence On geocryological and sedimentary processes ................................................................................... 4.4 Ground temperature measurements ..................................... 4.5 Investigation of ground ice .....................................................