Ice Age Megafauna and Time Notes Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mg2sio4) in a H2O-H2 Gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S

Goldschmidt2013 Conference Abstracts 2297 Compacted Nanoparticles for Evaporation behavior of forsterite Quantification in LA-ICPMS (Mg2SiO4) in a H2O-H2 gas DANIEL TABERSKY1, NORMAN LUECHINGER2, SAMUEL S. TACHIBANA1* AND A. TAKIGAWA2 2 2 1 , HALIM , MICHAEL ROSSIER AND DETLEF GÜNTHER * 1 Department of Natural History Sciences, Hokkaido 1ETH Zurich, Department of Chemistry and Applied University, N10 W8, Sapporo 060-0810, Japan. Biosciences, Laboratory of Inorganic Chemistry (*correspondence: [email protected]) (*correspondence: [email protected]) 2Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial 2Nanograde, Staefa, Switzerland Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington DC, 20015 USA. Gray et al. did first studies of LA-ICPMS in 1985 [1]. Ever since, extensive research has been performed to Forsterite (Mg2SiO4) is one of the most abundant overcome the problem of so-called “non-stoichiometric crystalline silicates in extraterrestrial materials and in sampling” and/or analysis, the origins of which are commonly circumstellar environments, and its evaporation behavior has referred to as elemental fractionation (EF). EF mainly consists been intensively studied in vacuum and in the presence of of laser-, transport- and ICP-induced effects, and often results low-pressure hydrogen gas [e.g., 1-4]. It has been known that in inaccurate analyses as pointed out in, e.g. references [2,3]. the evaporation rate of forsterite is controlled by a A major problem that has to be addressed is the lack of thermodynamic driving force (i.e., equilibrium vapor reference materials. Though the glass series of NIST SRM 61x pressure), and the evaporation rate increases linearly with 1/2 have been the most commonly reference material used in LA- pH2 in the presence of hydrogen gas due to the increase of ICPMS, heterogeneities have been reported for some sample the equilibrium vapor pressure. -

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

Waco Mammoth Site • Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment • Texas Waco Mammoth Site Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment

Waco Mammoth Site Waco National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Waco Mammoth Site • Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment • Texas Waco Mammoth Site Special Resource Study Special Resource / Environmental Assessment Environmental National Park Service • United States Department of the Interior Special Resource Study/Environmental Assessment Texas July • 2008 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national This report has been prepared to provide Congress and the public with information about parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor the resources in the study area and how they relate to criteria for inclusion within the recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure national park system. Publication and transmittal of this report should not be considered an that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship endorsement or a commitment by the National Park Service to seek or support either and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for specific legislative authorization for the project or appropriation for its implementation. American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under Authorization and funding for any new commitments by the National Park Service will have U.S. administration. to be considered in light of competing priorities for existing units of the national park system and other programs. -

Pleistocene Rodents of the British Isles

PLEISTOCENE RODENTS OF THE BRITISH ISLES BY ANTONY JOHN SUTCLIFFE British Museum (Natural History), London AND KAZIMIERZ KOWALSKI Institute of Systematic and Experimental Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow, Poland Pp. 31-147 ; 31 Text-figures ; 13 Tables BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM (NATURAL HISTORY) GEOLOGY Vol. 27 No. 2 LONDON: 1976 THE BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM (natural history), instituted in 1949, is issued in five series corresponding to the Scientific Departments of the Museum, and an Historical series. Parts will appear at irregular intervals as they become ready. Volumes will contain about three or four hundred pages, and will not necessarily be completed within one calendar year. In 1965 a separate supplementary series of longer papers was instituted, numbered serially for each Department. This paper is Vol. 27, No. 2, of the Geological [Palaeontological) series. The abbreviated titles of periodicals cited follow those of the World List of Scientific Periodicals. World List abbreviation : Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Geol. ISSN 0007-1471 Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), 1976 BRITISH MUSEUM (NATURAL HISTORY) Issued 29 July, 1976 Price £7.40 . PLEISTOCENE RODENTS OF THE BRITISH ISLES By A. J. SUTCLIFFE & K. KOWALSKI CONTENTS Page Synopsis ........ 35 I. Introduction ....... 36 A. History of Studies ..... 37 B. The Geological Background .... 40 II. Localities in the British Isles with fossil rodents 42 A. Deposits OF East Anglia . .... 42 (i) Red Crag 43 (ii) Icenian Crag ....... 43 (iii) Cromer Forest Bed Series ..... 46 (a) Pastonian of East Runton and Happisburgh 47 (b) Beestonian ...... 48 (c) Cromerian, sensu stricto .... 48 (d) Anglian ...... -

Historical Review Petroleum – Petroleum Use in Ancient Times Geology – Modern Petroleum Industry

GEOL493k Lecture Outline • Course logistics Advanced • Historical Review Petroleum – Petroleum use in ancient times Geology – Modern Petroleum Industry Geology 373 Intro Petroleum Geology Geology 493K Adv. Petroleum Geology Class Web Site: http://www.geo.wvu.edu/~jtoro/Petroleum/index.htm Instructor: Dr. Jaime Toro Prerequisites: Geology 101 Grades: Office: G39 White Hall • Test 1 – Feb. 10 (Wed) 20 % Phone: 293-9817 • Test 2 – Mar. 11 (Fri) 20 % Email: [email protected] • Test 3 – April 13 (Wed) 20% Office Hours: 1:30-2:30 MF • Test 4 – May 4 (Wed), 3:00-5:00 PM 20% Text: Elements of Petroleum Geology, • Weekly Reading Quizzes – 12% R. Selley. • Attendance – 8% Class Topics • 2. The petroleum system • 3. What is Petroleum? Historical Review • 4. The subsurface environment • 5. Well Drilling and completion • 6. Formation Evaluation Petroleum • 7. Sedimentary Basins and Sedimentary rocks • 8. The source: How oil forms (πετρέλαιον, Greek) • 9. Migration • 10. The Reservoir Petra= Rock • 11. Traps and Seals • 12. Geophysical Methods of Exploration Oleum= Oil • 13. Exploration Process • 14. Prospect Evaluation • 15. Field Development Term first used by Agricola in 1546 • 16. Unconventional Resources • 17. The future of the Petroleum Industry Genesis 6:13-16 La Brea Tar Pits, Los Angeles • “And God said onto Noah … make yourself an arc of gopher wood; make rooms in the arc and cover it inside and out with pitch” Oil Seep Oil seep Rock streaked by oil. Ventura County, CA. USGS photo Asphaltum in Oil seep in Santa Barbara, CA. USGS Photo Gas Seep Gas seeps on the seafloor Gas seep in Ventura County, CA emits methane, ethane, propane. -

Jens Esmark's Mountain Glacier Traverse 1823 À the Key to His

bs_bs_banner Jens Esmark’s mountain glacier traverse 1823 À the key to his discovery of Ice Ages GEIR HESTMARK Hestmark, G. 2018 (January): Jens Esmark’s mountain glacier traverse 1823 À the key to his discovery of Ice Ages. Boreas, Vol. 47, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12260. ISSN 0300-9483. The discovery of Ice Ages is one of the most revolutionary advances made in the Earth sciences. In 1824 Danish- Norwegian geoscientist Jens Esmark published a paper stating that there was indisputable evidence that Norway and other parts of Europe had previously been covered by enormous glaciers carving out valleys and fjords, in a cold climate caused by changes in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit. Esmark and his travel companion Otto Tank arrived at this insight byanalogous reasoning: enigmatic landscape features theyobserved close to sea level alongtheNorwegian coast strongly resembled features they observed in the front of a retreating glacier during a mountain traverse in the summer of 1823. Which glacier they observed up close has however remained a mystery, and thus an essential piece of information in the story of this discovery has been missing. Based on previously unknown archive sources, supplemented by field study, I here identify the key locality as the glacier Rauddalsbreen. This is the northernmost outlet glacier from Jostedalsbreen, the largest glacier in mainland Europe. Here the foreland exposed byglacier retreat since the Little Ice Age maximum around AD 1750 contains a rich collection of glacial deposits and erosional forms. The point of enlightenment is more precisely identified to be a specific moraine and its distal sandur at 61°53026″N, 7°26043″E. -

Jens Esmark – Meteorologist

1 2 Jens Esmark’s Christiania (Oslo) meteorological observations 3 1816-1838: The first long term continuous temperature record 4 from the Norwegian capital homogenized and analysed 5 6 7 Geir Hestmark1 and Øyvind Nordli2 8 9 1 Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis, CEES, Department of 10 Biosciences, Box 1066 Blindern, University of Oslo, N-0316 Oslo, Norway 11 2 Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET Norway), 12 Research and Development Department, Division for Model and Climate Analysis, 13 P.O. Box 43 Blindern, N-0313 Oslo, Norway 14 15 Correspondence to: Geir Hestmark ([email protected]) 16 17 Abstract 18 In 2010 we rediscovered the complete set of meteorological observation protocols 19 made by professor Jens Esmark (1762-1839) during his years of residence in the 20 Norwegian capital of Oslo (then Christiania). From 1 January 1816 to 25 January 21 1839 Esmark at his house in Øvre Voldgate in the morning, early afternoon and 22 late evening recorded air temperature with state of the art thermometers. He also 23 noted air pressure, cloud cover, precipitation and wind directions, and 24 experimented with rain gauges and hygrometers. From 1818 to the end of 1838 he 25 twice a month provided weather tables to the official newspaper Den norske 26 Rigstidende, and thus acquired a semi-official status as the first Norwegian state 27 meteorologist. This paper evaluates the quality of Esmark’s temperature 28 observations, presents new metadata, new homogenization and analysis of monthly 29 means. Three significant shifts in the measurement series were detected, and 30 suitable corrections are proposed. -

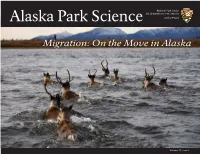

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology by Paul David Polly B.A. (University of Texas at Austin) 1987 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Paleontology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA at BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor William A. Clemens, Chair Professor Kevin Padian Professor James L. Patton Professor F. Clark Howell 1993 Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology © 1993 by Paul David Polly To P. Reid Hamilton, in memory. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ix Acknowledgments xi Chapter One--Revolution and Evolution in Taxonomy: Mammalian Classification Before and After Darwin 1 Introduction 2 The Beginning of Modern Taxonomy: Linnaeus and his Predecessors 5 Cuvier's Classification 10 Owen's Classification 18 Post-Darwinian Taxonomy: Revolution and Evolution in Classification 24 Kovalevskii's Classification 25 Huxley's Classification 28 Cope's Classification 33 Early 20th Century Taxonomy 42 Simpson and the Evolutionary Synthesis 46 A Box Model of Classification 48 The Content of Simpson's 1945 Classification 50 Conclusion 52 Acknowledgments 56 Bibliography 56 Figures 69 Chapter Two: Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) from the Early Eocene Four Mile Fauna and Their Biostratigraphic Implications 78 Abstract 79 Introduction 79 Materials and Methods 80 iv Systematic Paleontology 80 The Four Mile Fauna and Wasatchian Biostratigraphic Zonation 84 Conclusion 86 Acknowledgments 86 Bibliography 86 Figures 87 Chapter Three: A New Genus Eurotherium (Creodonta, Mammalia) in Reference to Taxonomic Problems with Some Eocene Hyaenodontids from Eurasia (With B. Lange-Badré) 89 Résumé 90 Abstract 90 Version française abrégéé 90 Introduction 93 Acknowledgments 96 Bibliography 96 Table 3.1: Original and Current Usages of Genera and Species 99 Table 3.2: Species Currently Included in Genera Discussed in Text 101 Chapter Four: The skeleton of Gazinocyon vulpeculus n. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

A37952) (A37952

(A37952) (A37952) Expert Opinion on Petroleum Tanker Accidents and Malfunctions in Browning Entrance and Principe Channel: Potential Marine Effects on Gitxaała Traditional Lands and Waters of a Spill During Tanker Transport of Bitumen from the Northern Gateway Pipeline Project (NGP) Contributors: CJ Beegle-Krause B. Emmett M. Hammond J. Short R. Spies Editor: L. Beckmann Prepared for: JFK Law Corporation, Counsel to Gitxaała First Nation 340 – 1122 Mainland Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5L1 December 2011 (A37952) Table of Contents 1.0 Background, Purpose and Scope of Work.......................................................................1 2.0 Report Structure .................................................................................................................1 3.0 Nearshore Habitats, Biological Communities, and Key Marine Resources .................2 3.1 Overview ..................................................................................................................2 3.2 Nearshore Physical Features...................................................................................3 3.3 Nearshore Habitats ..................................................................................................5 3.4 Nearshore Habitat Types and Oil Residency...........................................................9 3.5 Potentially Affected Marine Resources ..................................................................12 3.6 Critique of the Application with Respect to Habitat Issues ....................................13 -

The Largest Fossil Rodent Andre´S Rinderknecht1 and R

Proc. R. Soc. B doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1645 Published online The largest fossil rodent Andre´s Rinderknecht1 and R. Ernesto Blanco2,* 1Museo Nacional de Historia Natural y Antropologı´a, Montevideo 11300, Uruguay 2Facultad de Ingenierı´a, Instituto de Fı´sica, Julio Herrera y Reissig 565, Montevideo 11300, Uruguay The discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved skull permits the description of the new South American fossil species of the rodent, Josephoartigasia monesi sp. nov. (family: Dinomyidae; Rodentia: Hystricognathi: Caviomorpha). This species with estimated body mass of nearly 1000 kg is the largest yet recorded. The skull sheds new light on the anatomy of the extinct giant rodents of the Dinomyidae, which are known mostly from isolated teeth and incomplete mandible remains. The fossil derives from San Jose´ Formation, Uruguay, usually assigned to the Pliocene–Pleistocene (4–2 Myr ago), and the proposed palaeoenviron- ment where this rodent lived was characterized as an estuarine or deltaic system with forest communities. Keywords: giant rodents; Dinomyidae; megamammals 1. INTRODUCTION 3. HOLOTYPE The order Rodentia is the most abundant group of living MNHN 921 (figures 1 and 2; Museo Nacional de Historia mammals with nearly 40% of the total number of Natural y Antropologı´a, Montevideo, Uruguay): almost mammalian species recorded (McKenna & Bell 1997; complete skull without left zygomatic arch, right incisor, Wilson & Reeder 2005). In general, rodents have left M2 and right P4-M1. body masses smaller than 1 kg with few exceptions. The largest living rodent, the carpincho or capybara 4. AGE AND LOCALITY (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), which lives in the Neotro- Uruguay, Departament of San Jose´, coast of Rı´odeLa pical region of South America, has a body mass of Plata, ‘Kiyu´’ beach (348440 S–568500 W).