Colin Cookman1 June 4, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Responses to Honour Killings

CONTENTS TIIVISTELMÄ .....................................................................................V ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................... X 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................1 1.1 DEFINING AND CONTEXTUALISING HONOUR KILLINGS ....................................4 1.2 WHY ‘HONOUR KILLINGS’? SOME TERMINOLOGICAL REMARKS AS TO HONOUR AND PASSION ................................................................................................9 1.3 AIM AND STRUCTURE OF THE STUDY.............................................................13 2 STATE RESPONSES TO HONOUR KILLINGS .........................................15 2.1 LEGISLATION, LAW ENFORCEMENT AND ADJUDICATION RELEVANT TO HONOUR KILLINGS.....................................................................................................15 2.1.1 Codified means for mitigating penalties in honour killing cases................16 2.1.1.1 Discriminatory provisions relating to provocation and extenuating circumstances...................................................................................................16 2.1.1.2 The Qisas and Diyat Ordinance of Pakistan ........................................19 2.1.2 Discriminatory application of general provocation and extenuating circumstances provisions .....................................................................................21 2.1.3 Honour killings and the impact of culture, traditions and customs -

Download Article

Pakistan’s ‘Mainstreaming’ Jihadis Vinay Kaura, Aparna Pande The emergence of the religious right-wing as a formidable political force in Pakistan seems to be an outcome of direct and indirect patron- age of the dominant military over the years. Ever since the creation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1947, the military establishment has formed a quasi alliance with the conservative religious elements who define a strongly Islamic identity for the country. The alliance has provided Islamism with regional perspectives and encouraged it to exploit the concept of jihad. This trend found its most obvious man- ifestation through the Afghan War. Due to the centrality of Islam in Pakistan’s national identity, secular leaders and groups find it extreme- ly difficult to create a national consensus against groups that describe themselves as soldiers of Islam. Using two case studies, the article ar- gues that political survival of both the military and the radical Islamist parties is based on their tacit understanding. It contends that without de-radicalisation of jihadis, the efforts to ‘mainstream’ them through the electoral process have huge implications for Pakistan’s political sys- tem as well as for prospects of regional peace. Keywords: Islamist, Jihadist, Red Mosque, Taliban, blasphemy, ISI, TLP, Musharraf, Afghanistan Introduction In the last two decades, the relationship between the Islamic faith and political power has emerged as an interesting field of political anal- ysis. Particularly after the revival of the Taliban and the rise of ISIS, Author. Article. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 14, no. 4: 51–73. -

Book Pakistanonedge.Pdf

Pakistan Project Report April 2013 Pakistan on the Edge Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in ISBN: 978-93-82512-02-8 First Published: April 2013 Cover shows Data Ganj Baksh, popularly known as Data Durbar, a Sufi shrine in Lahore. It is the tomb of Syed Abul Hassan Bin Usman Bin Ali Al-Hajweri. The shrine was attacked by radical elements in July 2010. The photograph was taken in August 2010. Courtesy: Smruti S Pattanaik. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. Published by: Magnum Books Pvt Ltd Registered Office: C-27-B, Gangotri Enclave Alaknanda, New Delhi-110 019 Tel.: +91-11-42143062, +91-9811097054 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magnumbooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). Contents Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Political Scenario: The Emerging Trends Amit Julka, Ashok K. Behuria and Sushant Sareen 13 Chapter 2 Provinces: A Strained Federation Sushant Sareen and Ashok K. Behuria 29 Chapter 3 Militant Groups in Pakistan: New Coalition, Old Politics Amit Julka and Shamshad Ahmad Khan 41 Chapter 4 Continuing Religious Radicalism and Ever Widening Sectarian Divide P. -

Six-Member Caretaker Cabinet Takes Oath

Six-member caretaker cabinet takes oath Page NO.01 Col NO.04 ISLAMABAD: President Mamnoon Hussain swearing in the six-member cabinet during a ceremony at the Presidency on Tuesday. Caretaker Prime Minister retired justice Nasirul Mulk is also seen.—APP ISLAMABAD: A six-member caretaker cabinet took the oath on Tuesday to run the day- to-day affairs of the interim government. President Mamnoon Hussain administered the oath to the cabinet members. Caretaker Prime Minister retired Justice Nasirul Mulk was present at the oath-taking ceremony held at the presidency. The six-member cabinet comprises former governor of the State Bank of Pakistan Dr Shamshad Akhtar, senior lawyer Barrister Syed Ali Zafar, former ambassador of Pakistan to the United Nations Abdullah Hussain Haroon, educationist Muhammad Yusuf Shaikh, educationist and human rights expert Roshan Khursheed Bharucha and former federal secretary Azam Khan. Two out of six members of the cabinet have also served during the tenure of former military ruler retired Gen Pervez Musharaf: Dr Akhtar as SBP governor and Ms Bharucha as senator. Besides running the affairs of the interim set-up, the cabinet members will also assist the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) in holding fair and free elections in the country. It is expected that more members will be inducted into the cabinet in the coming days. Two women among federal ministers, both of whom worked during Musharraf regime Following the oath-taking ceremony, portfolios were given to the ministers. According to a statement issued by the Prime Minister Office, Dr Akhtar has been given finance, revenue and economic affairs. -

FAFEN Key Findings and Analysis for 2018 Pakistan Elections

Key Findings and Analysis www.fafen.org 1 Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) FAFEN General Election Observation 2018 Key Findings and Analysis All rights reserved. Any part of this publication may be produced or translated by duly acknowledging the source. TDEA–FAFEN Secretariat Building No. 1, Street 5 (Off Jasmine Road), G-7/2, Islamabad, Pakistan Website: www.fafen.org FAFEN is supported by Trust for Democratic Education and Accountability (TDEA) 2 Free and Fair Election Network - FAFEN Key Findings and Analysis www.fafen.org 3 4 Free and Fair Election Network - FAFEN AAT Allah-o-Akbar Tehreek ANP Awami National Party ARO Assistant Returning Officer ASWJ Ahle Sunnat-Wal-Jamaat BAP Balochistan Awami Party BNP Balochistan National Party CC Constituency Coordinator CERS Computerized Electoral Rolls System CSO Civil Society Organization DC District Coordinator DDC District Development Committee DEC District Election Commissioner DMO District Monitoring Officer DRO District Returning Officer DVEC District Voter Education Committees ECP Election Commission of Pakistan EDO Election Day Observer EIMS Election Information Management System FAFEN Free and Fair Election Network FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FGD Focus Group Discussion GDA Grand Democratic Alliance GE General Election GIS Geographic Information System ICT Islamabad Capital Territory JI Jamaat-e-Islami JUIF Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam (Fazl) KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa LEA Law Enforcement Agencies LG Local Government MMA Muttahida Majalis-e-Amal MML Milli Muslim League MQMP Muttahida -

117Th Edition

EOC COMMUNICATION UPDATE Issue no. 117 IVv brick EOC Communication update 117th Edition WWW.ENDPOLIO.COM.PK ISSUE NO. 117 – MAY 20, 2017 Murad Ali Shah vows to make Sindh polio-free The Sindh Chief Minister Syed Murad Ali Shah has said that he was committed to eradicate polio from Sindh but this is a national issue and all the provincial governments have to combat it in their respective areas, otherwise this threat would always be looming large. He said while presiding over a meeting on the `Provincial Task Force Meeting for Polio Eradication' here at the CM House. Health Minister Dr Sikandar Mendhro, Aseefa Bhutto Zaradri, MNA Azra Pechuho, Chief Secretary Rizwan Memon, Mayor of Karachi Waseem Akhtar, IG Police AD Khowaja, Coordinator Emergency Operation Center for Polio Fayaz Jatoi and the representatives of the federal government, UNICEF, WHO, provincial secretaries were also present on the occasion. The chief minister said that he was giving extraordinary attention to the ongoing polio drive by ensuring security arrangements for the teams. "Therefore, I want to make Sindh free of polio." He was quite satisfied when he received the report that during the current five months of 2017 no polio case has been reported anywhere from Sindh. "I hope this year would prove to be zero polio year". Briefing the meeting, Coordinator Emergency Operation Center for Polio Fayaz Jatio said that during the first five months of 2017 only two polio cases have been reported in the country, one in Gilgit -Baltistan and other one in Punjab. He added that during 2014, some 30 polio cases had emerged in Sindh. -

FAULTLINES the K.P.S

FAULTLINES The K.P.S. Gill Journal of Conflict & Resolution Volume 26 FAULTLINES The K.P.S. Gill Journal of Conflict & Resolution Volume 26 edited by AJAI SAHNI Kautilya Books & THE INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. © The Institute for Conflict Management, New Delhi November 2020 ISBN : 978-81-948233-1-5 Price: ` 250 Overseas: US$ 30 Printed by: Kautilya Books 309, Hari Sadan, 20, Ansari Road Daryaganj, New Delhi-110 002 Phone: 011 47534346, +91 99115 54346 Faultlines: the k.p.s. gill journal of conflict & resolution Edited by Ajai Sahni FAULTLINES - THE SERIES FAULTLINES focuses on various sources and aspects of existing and emerging conflict in the Indian subcontinent. Terrorism and low-intensity wars, communal, caste and other sectarian strife, political violence, organised crime, policing, the criminal justice system and human rights constitute the central focus of the Journal. FAULTLINES is published each quarter by the INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. PUBLISHER & EDITOR Dr. Ajai Sahni ASSISTANT EDITOR Dr. Sanchita Bhattacharya EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Prof. George Jacob Vijendra Singh Jafa Chandan Mitra The views expressed in FAULTLINES are those of the authors, and not necessarily of the INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. FAULTLINES seeks to provide a forum for the widest possible spectrum of research and opinion on South Asian conflicts. Contents Foreword i 1. Digitised Hate: Online Radicalisation in Pakistan & Afghanistan: Implications for India 1 ─ Peter Chalk 2. -

Pakistan Elections 2018: an Analysis of Trends, Recurring Themes and Possible Political Scenarios

1 DISCUSSION PAPER Dr. Saeed Shafqat * Professor & Founding Director Centre for Public Policy and Governance (CPPG) Pakistan Elections 2018: An Analysis of Trends, Recurring Themes and Possible Political Scenarios Abstract Politics in Pakistan like many developing societies is confrontational, personalized and acrimonious, yet electoral contestations provides an opportunity for resolving divides through bargain, compromise and consensus. On 25th July 2018 Pakistani voters will be choosing new national and provincial assemblies for the next five years. Forecasting electoral outcomes is hazardous, yet this paper ventures to provide an appraisal of some key issues, current trends, and recurring themes and based on an analysis of limited data and survey of literature and news reports presents a few scenarios about the potential loosers and winners in the forthcoming elections. Introduction and Context: This paper is divided into five parts and draws attention towards key issues that are steering the elections 2018. First, Identifying the current trends, it sheds some light on 2013 elections and how the Census 2017 and youth bulge could influence the outcome of 2018 elections. Second, it highlights the revitalization of Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) and how it would test its ability to hold free and fair elections. Third, it focuses on the confrontational politics of Sharif Family and PML-N and how the opposition political parties and the military is responding to it and that could set new parameters for civil-military relations in the post election phase. Fourth, it dwells on the role media and social media could play in shaping the electioneering and outcome of the elections. -

A Content Analysis of Current Affairs Talk Shows on Pakistani News Channels

Vol.2 Issue.2 June-2021 Global Media and Social Sciences Research Journal (Quarterly) Page-14-24 Social Sciences Website: http://www.gmssrj.com ISSN:2709-3433 (Online) Multidisciplinar Email:[email protected],[email protected] ISSN:2709-3425 (Print) y A Content Analysis of Current Affairs Talk Shows on Pakistani News Channels Tufail Akram1 Rahman Ullah2 Fazli Wahid3 1BS Student,Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. 2Lecturer, Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. 3Lecturer, Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. Abstract Keywords This study is designed to find out that what are the major themes and Content concepts in the current affair talk shows of Pakistani media. Talk Analysis, shows of news channels provide information and opinion regarding Pakistan, Government Policy, Politics and Socio-economic concerns, Education, Sensationalism, Health and Development etc. To reach the objectives, we adopted Talk Shows, qualitative methodology with thematic analysis to analyze the contents Tv Channels, broadcasted in seven different current affairs talk shows that on- aired Political Parties, in the prominent television news channel of Pakistan. Total 225 Talk Politics. shows were analyzed during two months (September and October 2020). The seven talk shows were selected through the purposive sampling method included, Capital Talk, Ajj Shahzeb Khanzada ke Sath, 11th Hour, News Eye, Hard Talk Pakistan, Breaking Point with Malick, and On the Front. The finding of the study indicates that the Majority of the time (70 %) was given to political issues and less than 1% of the time given to education, health, development and economy. -

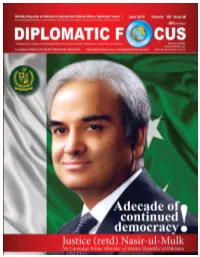

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 09 10 19 31 09 Close and fraternal relations between Turkey is playing a very positive role towards the resolution Pakistan & Turkey are the guarantee of of different international issues. Turkey has dealt with the stability and prosperity in the region: Middle East crisis and especially the issue of refugees in a very positive manner, President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former Former CJP Nasirul Mulk was born on August 17, 1950 in CJP Nasirul Mulk Mingora, Swat. He completed his degree of Bar-at-Law from Inner Temple London and was called to the Bar in 1977. 19 President Emomali Rahmon expressed The sides discussed the issues of strengthening bilateral satisfaction over the friendly relations and cooperation in combating terrorism, extremism, drug multifaceted cooperation between production and transnational crime. Tajikistan & Pakistan 31 Colorful Cultural Exchanges between China and Pakistan are not only friendly neighbors, but also China and Pakistan two major ancient civilizations that have maintained close ties in cultural exchanges and mutual learning. The Royal wedding 2018 Since announcing their engagement in 13 November 2017, the world has been preparing for Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s royal wedding. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex begin their first day as a married couple following an emotional ceremony that captivated the nation and a night spent partying with close family and friends. 06 Diplomatic Focus June 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 Pakistan & Turkey Close and fraternal relations …: President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former CJP Nasirul Mulk 12 The Royal wedding2018 Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 14 Pakistan & Saudi Arabia are linked through deep historic, religious and cultural Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain relations Patron in Chief: Mr. -

Qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasProfiles of Political Personalities dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc 22 Table of Contents 1. Mutahidda Qaumi Movement 11 1.1 Haider Abbas Rizvi……………………………………………………………………………………….4 1.2 Farooq Sattar………………………………………………………………………………………………66 1.3 Altaf Hussain ………………………………………………………………………………………………8 1.4 Waseem Akhtar…………………………………………………………………………………………….10 1.5 Babar ghauri…………………………………………………………………………………………………1111 1.6 Mustafa Kamal……………………………………………………………………………………………….13 1.7 Dr. Ishrat ul Iad……………………………………………………………………………………………….15 2. Awami National Party………………………………………………………………………………………….17 2.1 Afrasiab Khattak………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.2 Azam Khan Hoti……………………………………………………………………………………………….19 2.3 Asfand yaar Wali Khan………………………………………………………………………………………20 2.4 Haji Ghulam Ahmed Bilour………………………………………………………………………………..22 2.5 Bashir Ahmed Bilour ………………………………………………………………………………………24 2.6 Mian Iftikhar Hussain………………………………………………………………………………………25 2.7 Mohad Zahid Khan ………………………………………………………………………………………….27 2.8 Bushra Gohar………………………………………………………………………………………………….29 -

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`I Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!Q

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!q Photo Credit: AP Photo/B.K. Bangash December 2014 ! Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence since 2007 Arif Rafiq! DECEMBER 2014 1 ! ! Contents ! ! I. Summary ................................................................................. 3! II. Acronyms ............................................................................... 5! III. The Author ............................................................................ 8! IV. Introduction .......................................................................... 9! V. Historic Roots of Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Conflict in Pakistan ...... 10! VI. Sectarian Violence Surges since 2007: How and Why? ............ 32! VII. Current Trends: Sectarianism Growing .................................. 91! VIII. Policy Recommendations .................................................. 105! IX. Bibliography ..................................................................... 110! X. Notes ................................................................................ 114! ! 2 I. Summary • Sectarian violence between Sunni Deobandi and Shi‘i Muslims in Pakistan has resurged since 2007, resulting in approximately 2,300 deaths in Pakistan’s four main provinces from 2007 to 2013 and an estimated 1,500 deaths in the Kurram Agency from 2007 to 2011. • Baluchistan and Karachi are now the two most active zones of violence between Sunni Deobandis and Shi‘a,