Guest Editor's Introduction: Homing Missile Guidance and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Winning the Salvo Competition Rebalancing America’S Air and Missile Defenses

WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK 2016 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2016 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004. Mark was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review. Following the QDR, he served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, a Master of Public Administration from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. in chemistry from the United States Air Force Academy. -

Cruise Missiles Post World War II

Cruise missiles milestones MILE post STONES World War II Dr Carlo Kopp THE BASIC TECHNOLOGY AND OPERATIONAL CONCEPT OF MODERN CRUISE MISSILES EMERGED DURING THE LATE 1960S, at the peak of the Cold War era. This type of weapon was exemplified by the RGM-109 Tomahawk series, the AGM-86C/D CALCM, the AGM-158 JASSM, and the Russian Kh-55SM Granat. Much less known is the generation of cruise missile technology that supplanted the 1940s era FZG-76/V-1 and its Russian and American clone variants. A good number of the former Soviet weapons of this generation remain in use, some still in production. The aim of all cruise missile designs is to provide a weapon that can strike at a target while not exposing the launch platform to attack by enemy defences, whether the launch platform is an aircraft, surface warship, submarine or ground vehicle. Key parameters in the design of any cruise missile are its standoff range, its accuracy and its survivability against target defences. Increasing standoff range reduces risk to the launch platform while increasing accuracy and survivability reduces the number of launches required to achieve desired effect. The economics of bombardment are simple: the more expensive the weapon employed, the smaller the war stock available for combat at any time, and the longer it takes to replenish this war stock once expended. Northrop SM-62 Snark strategic cruise missile. This enormous 50,000 lb plus GLCM was built to directly attack the Soviet Union from US basing. It introduced the fi rst stellar-inertial guidance system in a cruise missile. -

GAO WEAPONS ACQUISITION Precision Guided Munitions In

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Committees June 1995 WEAPONS ACQUISITION Precision Guided Munitions in Inventory, Production, and Development GAO/NSIAD-95-95 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-260458 June 23, 1995 Congressional Committees The military services are spending billions of dollars to acquire new and improved munitions whose technical sophistication allows guidance corrections during their flight to the target. These weapons are referred to as precision guided munitions (PGM). We reviewed Air Force, Navy, and Army munitions programs in inventory, production, and development that could be defined as using precision guidance to attack surface targets.1 Our objectives were to determine (1) the costs and quantities planned for the PGMs, (2) the services rationale for initiating PGM development programs, (3) options available to the services to attack surface targets with PGMs, and (4) the extent to which the services are jointly developing and procuring PGMs. We conducted this work under our basic legislative responsibilities and plan to use this baseline report in planning future work on Defense-wide issues affecting the acquisition and effectiveness of PGMs. We are addressing the report to you because we believe it will be of interest to your committees. PGMs employ various guidance methods to enhance the probability of Background hitting the target. These include target location information from a human designator, global positioning system (GPS) satellites, an inertial navigation system, a terminal seeker on the munition, or a combination of these sources. Since PGMs can correct errors in flight, the services expect to need fewer rounds to achieve the same or higher probabilities of kill as unguided weapons. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

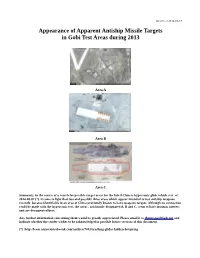

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

Spacecraft Guidance Techniques for Maximizing Mission Success

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2014 Spacecraft Guidance Techniques for Maximizing Mission Success Shane B. Robinson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Shane B., "Spacecraft Guidance Techniques for Maximizing Mission Success" (2014). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2175. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2175 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPACECRAFT GUIDANCE TECHNIQUES FOR MAXIMIZING MISSION SUCCESS by Shane B. Robinson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Mechanical Engineering Approved: Dr. David K. Geller Dr. Jacob H. Gunther Major Professor Committee Member Dr. Warren F. Phillips Dr. Charles M. Swenson Committee Member Committee Member Dr. Stephen A. Whitmore Dr. Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2013 [This page intentionally left blank] iii Copyright c Shane B. Robinson 2013 All Rights Reserved [This page intentionally left blank] v Abstract Spacecraft Guidance Techniques for Maximizing Mission Success by Shane B. Robinson, Doctor of Philosophy Utah State University, 2013 Major Professor: Dr. David K. Geller Department: Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Traditional spacecraft guidance techniques have the objective of deterministically min- imizing fuel consumption. -

Missile Guidance and Control

CHAPTER 4 MISSILE GUIDANCE AND CONTROL INTRODUCTION in the interest of terminology standardization and to assist common understanding, we shall call the In the preceding chapters you learned that the complete system within a missile that steers and essential parts a guided missile needs to perform stabilizes it a guidance and control system. properly are: Depending on your experience with missiles, you 1. Airframe and control surfaces. may take exception to this designation. And if you 2. Propulsion system. do, there is good reason for it. The reason is shown 3. Warhead system. in figure 4-1. For example, if you have worked on 4. Guidance and control system. the Tartar or Terrier missiles you will consider the In addition, in chapter 2 you studied the basic fire system that guides and controls a missile to be its control problem, and learned how some of the steering system. On the other hand, a Talos GMM forces of nature affect the trajectory of a guided would call it a guidance and control system. We missile as it flies to its intended target. In chapter 3 will stick with the latter designation - not because you learned how wings and fins steer a missile and we favor Talos but because most manuals, and keep it pointed along its flight path. The use of many Navy publications, use this term. interior control devices by missiles without exterior control surfaces (or limited ones) was described SUBSYSTEMS AND COMPONENTS briefly. The different types of guidance systems used in missiles are inertial, command, beam-rider, In figure 4-2 we show that the complete system and homing guidance. -

Defense Primer: Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) Capabilities

November 10, 2020 Defense Primer: Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) Capabilities Figure 1. Notional GBSD Launch Status of Minuteman III MMIII first entered service around 1970 and has undergone several life extension programs over the past 50 years, the most recent of which occurred in the late 2000s and included a replacement booster and missile guidance computer. In the next decade, both of these components may face reliability concerns as they reach the end of their intended lifespan, known as aging out, as indicated in Figure 2. A 2016 Pentagon study recommended replacing MMIII rather than conducting another life extension. The study concluded that the replacement system (GBSD) would meet current and expected threats, maintain the industrial base, insert more reliable technology, produce a modular weapon system concept, and reduce life cycle cost. Source: https://www.northropgrumman.com/GBSD/ Figure 2. Projected Decrease in Operational Minuteman III Missiles On September 8, 2020, the United States Air Force awarded Northrop Grumman Corporation a $13.3 billion contract to develop a new nuclear missile, the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), intended to replace the 50-year old Minuteman III (MMIII) Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). (For details on the U.S. nuclear force structure, see CRS Report FL33640, U.S Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues, by Amy Woolf.) MMIII has been deployed as the ground-based leg of the U.S. nuclear forces structure (the “Triad”) since 1970. The Air Force expects GBSD to begin replacing MMIII in 2029. As the missile moves toward production and deployment, Source: Mark Gunzinger, Carl Rehberg, and Gillian Evans, Sustaining issues for Congress include whether to authorize and the US Nuclear Deterrent: The LRSO and GBSD, Center for appropriate funding for this program and, if so, to provide Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. -

Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GN&C) Efficient, Responsive, and Effective

Space Transportation Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GN&C) Efficient, Responsive, and Effective The GN&C capability is a critical enabler of • Navigation — system architecture trade every launch vehicle and spacecraft system. studies, sensor selection and modeling, posi- At-A-Glance Marshall applies a robust, responsive, team- tion/orientation determination software (filter) Guidance, navigation, and control capabilities oriented approach to the GN&C design, develop- development, architecture trade studies, auto- will be needed for today’s launch and tomor- ment, and test capabilities. From initial concept matic rendezvous and docking (AR&D), and row’s in-space applications. Marshall has through detailed mission analysis and design, Batch estimation — all mission phases. developed a GN&C capability with experience hardware development and test, verification and • Control — algorithms, vehicle and control directly supporting projects and serving as validation, and mission operations, the Center system requirements and specifications, a supplier and partner to industry, DOD, and can provide the complete end-to-end GN&C stability analyses, and controller design, academia. To achieve end-to-end develop- development and test — or provide any portion modeling and simulation. ment, this capability leverages tools such as of it — for launch vehicles or spacecraft systems the Flight Robotics Lab, specialized software • Sensor Hardware — selection, closed for any NASA mission. Recognized as the tools, and the portable SPRITE small satellite loop testing and qualification; design, build, Agency’s lead and a world-class developer of payload integration environment. The versatile and calibrate specialized sensors. Earth-to-orbit and in-space stages for GN&C, team also provides an anchor and resource Marshall is a key developer of in-space transpor- for government “smart buyer” oversight of tation, spacecraft control, automated rendezvous future space system acquisition, helping to and capture techniques, and testing.