Lectionaries in the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Pericope Adulterae: a Most Perplexing Passage

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1, 91–114. Copyright © 2018 Andrews University Seminary Studies. PERICOPE ADULTERAE: A MOST PERPLEXING PASSAGE Steven Grabiner Collegedale, Tennessee Abstract The account of the woman caught in adultery, traditionally found in John’s Gospel, is full of encouragement to sinners in need of for- giveness. Nevertheless, due to its textual history, this story—referred to as the Pericope Adulterae—is considered by many scholars to be an interpolation. The textual history is one of the most intriguing of any biblical passage. This article reviews that history, examines possible reasons for the passage’s inclusion or exclusion from John’s Gospel, engages discussion on the issue of its canonicity, and gives suggestions for how today’s pastors might relate to the story in their preaching. Keywords: Pericope Adulterae, adulteress, textual history, canon, textual criticism Introduction The story of the woman caught in adultery, found in John 7:52–8:11, contains a beautiful and powerful portrayal of the gospel. It has no doubt encouraged countless believers from the time it was first written. Despite the power in the story, it is unquestionably one of the most controverted texts in the New Testament (NT). Unfortunately, when a conversation begins regarding the textual variations connected with this account, emotions become involved and if the apostolic authorship is questioned and its place in the canon threatened, then, no matter the reasoning or the evidence, the theological pull frequently derails a calm discussion. Fears of releasing a river of unbelief that will sweep away precious truth and create a whirlpool of doubt arise. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century Jasperse, T.G. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Jasperse, T. G. (2013). The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century. Boxpress. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 The Gospel Book and the verbal and visual construction of Matilda’s identity 159 For many decades historians, art historians and palaeographers could not directly study the famous gospel book that Henry the Lion and Matilda com- missioned and donated to the Church of St Blaise. Somewhere in the 1930s, the manuscript disappeared, only to turn up at a Sotheby’s auction in 1983. -

CAPTIVE to the WORD Martin Luther: Doctor of Sacred Scripture

CAPTIVE TO THE WORD Martin Luther: Doctor of Sacred Scripture by A. SKEVINGTON WOOD B.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S. "I am bOIIIIII by the Scriptures ••• and my conscima Is capti11e to the Word of God". Martin Luther THE PATERNOSTER PRESS SBN: 85364 o87 4 Copyright© 1969 The Pakrnoster Press AusTRALtA,: Emu Book Agendes Pty., Ltd., 511, Kent Street, Sydney, N.S.W. CANADA: Home Evangel Books Ltd., 25, Hobson Avenue, Toronto, 16 NEW ZEALAND: G. W. Moore, Ltd., J, Campbell Road, P.O. Box 24053, Royal Oak, Auckland, 6 SOUTH AFRICA: Oxford University Press, P.O. Box 1141, Thibault House, Thibault Square, Cape Town Made and Printed in Great Britain for The Paternoster Press Paternoster House 3 Mount Radford Crescent Exeter Devon by Cox & Wyman Limited Fakenham By the Same Author THE BURNING HEART John Wesley, Evangelist THE INEXTINGUISHABLE BLAZE Spiritual Renewal and Advance in the Eighteenth Century VoL. VII in the PATERNOSTER CHURCH HISTORY PAUL'S PENTECOST Studies in the Life of the Spirit from Rom. 8 CONTENTS page PREFACE 7 PART I. THE BIBLE AND LUTHER I. LUTHER's INTRODUCTION TO THE SCRIPTURES II 11. LUTHER's STRUGGLE FOR FAITH 21 Ill. LuTHER's DEBT TO THE PAST 31 IV. LUTHER's THEOLOGICAL DI!VELOPMENT 41 V. LUTHER's ENcouNTER WITH GoD SI VI. LuTHER's STAND FoR THE TRUTH . 61 PART 11. LUTHER AND THE BIBLE (a) Luther's Use of Scripture VII. LUTHER AS A COMMENTATOR 7S VIII. LUTHER AS A PREACHER ss IX. LUTHER AS A TRANSLATOR • 9S X. LUTHER AS A REFORMER lOS (b) Luther's View of Scripture XI. -

Removing Anti-Jewish Polemic from Our Christian Lectionaries: a Proposal | Beck, Norman A

Jewish-Christian Relations Insights and Issues in the ongoing Jewish-Christian Dialogue Removing Anti-Jewish Polemic from our Christian Lectionaries: A Proposal | Beck, Norman A. A New Testament scholar examines the problem of anti-Jewish polemic in the weekly scripture portions read in Catholic and Protestant churches and proposes a new lectionary that avoids such material. Removing Anti-Jewish Polemic from our Christian Lectionaries: A Proposal by Norman A. Beck I. Defamatory Anti-Jewish Polemic in Christian Lectionaries During the past few decades, increasing numbers of mature Christians who read and study the specifically Christian New Testament texts critically have become painfully aware of the supersessionistic and vicious, defamatory anti-Jewish polemic that is included in some of these texts. Although many Jews have been aware of these texts throughout the history of Christianity, most Christians have been insensitive to the nature of these texts and to the damage that these texts and the use of these texts have done to Jews throughout the history of Christianity and especially since the fourth century of the common era when mainline Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire.1 Our concern in this section of the present study is focused on the inclusion of these religiously racist defamatory anti-Jewish texts in our Christian lectionaries. We shall examine specific lectionaries here to document the extent of inclusion of defamatory anti-Jewish texts, focusing primarily on the so-called "historic pericopes" in the form in which they were used by the majority of Christians prior to 1969, in the Lectionary for Mass as it was used by Roman Catholic Christians during the mid-1980s, on the Lutheran adaptations of the Lectionary for Mass that are included in the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978), and on the Revised Common Lectionary published by the Consultation on Common Texts in 1992. -

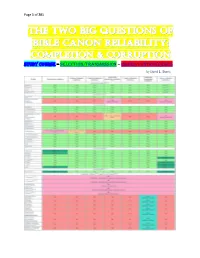

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration. -

The Eusebian Canons: an Early Catholic Approach to Gospel Harmony

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Sacred Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-1994 The Eusebian Canons: An Early Catholic Approach to Gospel Harmony Edward Engelbrecht Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/stm Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Engelbrecht, Edward, "The Eusebian Canons: An Early Catholic Approach to Gospel Harmony" (1994). Master of Sacred Theology Thesis. 49. https://scholar.csl.edu/stm/49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Sacred Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xi Chapter 1. Early Approaches to Harmonization in Near Eastern, Classical, and Christian Literature 1 1.1. The Philosophical and Doctrinal Foundations • 1 1.1.1. The Language of Harmonization 1 1.1.2. Extra Ecclesiam: Philosophical Analogy 5 1.1.3. Intra Ecclesiam: Theological Analogy . • 7 1.2. The Use of Sources by Ancient Historians . 12 1 .2.1. Mesopotamia 12 1.2.2. Egypt 14 1.2.3. Israel 15 1.2.4. Greece 18 1.2.5. The Evangelists 21 1.3. The Gattunqen of Harmonization 23 1.3.1. Rewriting 23 1.3.1.1. Mesopotamia 23 1.3.1.2. Israel 25 1.3.1.3. -

Sorrow, Beauty, and the Mystery of God's Love

Word & World Volume 41, Number 3 Summer 2021 Sorrow, Beauty, and the Mystery of God’s Love: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary’s Wisdom Texts AMY C. SCHIFRIN ach new liturgical year is framed with a word of death and a word of life. It is a time to be born and a time to die. A time, a time, a time . It doesn’t matter if it’sE year A, B, or C. On January 1, the Revised Common Lectionary’s texts given to us begin with Ecclesiastes 3.1 We can break a thousand New Year’s resolutions in a lifetime, and we can wish for each new year to be better than the last, but when we hear this text, we know that we would be fools to think that we know exactly what 2022 or 2023 or 2024 will have in store for us or for any of God’s children. All we know is that as this world spins on its axis, this pattern of being born and dying, of ecstasy and sorrow, of reunions and longings, of shatterings and mend- ings, of standing on precipice after precipice in food lines or refugee camps, county jails or gated communities, nursing homes or NICUs—all we know is that God is 1 A distinct service for New Year’s Day comes to us from the Presbyterian household. For those who celebrate Name of Jesus on January 1, there is a separate set of texts. See The Revised Common Lectionary: Twen- tieth Anniversary Annotated Edition (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992, 2012), 8, 62, 118. -

He Lectionary , Sources and History , Would No T Be Unwelcome

HE LECT IO N A RY ITS SO UR CES AN D H I STO RY JULES BAUDO T BENEDI CTI NE OF FARNBOROU G H TRANSLAT ED FRO M THE FRENCH BY A MBROS E CA TOR O F T HE ORATORY LONDON C A T H O L I C T R U T H S O C I E T Y 68 T A K B I DGE AD E SO U HW R R RO , S . 1 9 1 0 TR AN SLATO R ’S PR EFACE ’ ’ I S o a u t ho r s o L e B revia ire TH bo k , like the previ us one , R oma in a translati o n o f which was published by the , 1 C 1 0 o f atholic Truth Society in 9 9 , is one a series which ha s been appearing in French under the o o f R R D o m Ca b ro l A directi n the ight everend , bbot o f F o o arnb r ugh . The translator ha s ventured to add the present o ne t o E o n o the nglish works liturgy in the h pe that , f o f ollowing a knowledge the Breviary, some account o f it s the Lectionary , sources and history , would no t be unwelcome . l o In rea ity this is something more than a translati n . 2 is o f t w o It rather an adaptation works , to which a considerable amount o f new matter ha s been added b o f y the author . -

7 February 2021 Fifth Sunday After Epiphany Reflections on Lectionary Readings (RCL)1

7 February 2021 Fifth Sunday after Epiphany Reflections on Lectionary Readings (RCL)1 Scripture (JPS) 2 Isaiah 40:21-31 Do you not know? Have you not heard? Have you not been told from the very first? Have you not discerned how the earth was founded?d 22 It is He who is enthroned above the vault of the earth, So that its inhabitants seem as grasshoppers. Who spread out the skies like gauze, Stretched them out like a tent to dwell in. 23 He brings potentates to naught, Makes rulers of the earth as nothing. 24 Hardly are they planted, hardly are they sown, Hardly has their stem taken root in earth, When He blows upon them and they dry up, And the storm bears them off like straw. 25 To whom, then, can you liken Me, To whom can I be compared? —says the Holy One. 26 Lift high your eyes and see: Who created these? He who sends out their host by count, Who calls them each by name: Because of His great might and vast power, Not one fails to appear. 27 Why do you say, O Jacob, Why declare, O Israel, “My way is hid from the LORD, My cause is ignored by my God”? 28 Do you not know? Have you not heard? The LORD is God from of old, Creator of the earth from end to end, He never grows faint or weary, His wisdom cannot be fathomed. 29 He gives strength to the weary, Fresh vigor to the spent. 1 RCL: The Revised Common Lectionary is the prescribed scripture readings (pericopae) Bible for use in Christian worship, making provision for the liturgical year with its pattern of observances of festivals and seasons. -

Strange Encounters of a Lectionary Kind

Restoration Quarterly Volume 37 Number 4 Article 3 10-1-1995 Strange Encounters of a Lectionary Kind Tim Sensing Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sensing, Tim (1995) "Strange Encounters of a Lectionary Kind," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 37 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol37/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. R esLoRatJon uaRLer<LcY VOLUME 37/NUMBER 4 FOURTH QUARTER 1995. ISSN 0486-5642 K. C. Moser and Churches of Christ : A Theological Perspective JOHN MARK HICKS Philo on Pilate: Rhetoric or Reality? TOM THATCHER The Newly Discovered Fragmentary Aramaic Inscription from Tel Dan JOHN T. WILLIS Strange Encounters of a Lectionary Kind TIM SENSING Book Reviews Book Notes STRANGE ENCOUNTERS OF A LECTIONARY KIND TIM SENSING Burlington, NC Introduction Churches of Christ have a strong tradition of arbitrarily choosing sermon texts over the course of a year. These decisions are sometimes made with careful planning and evaluation of community needs and comprehensive coverage of Scripture. But sometimes these decisions are made every week with little forethought about the comprehensive diet the congregation is receiv ing over an extended time . -

1 Reading God's Word: the Legtionary

salie ae lecture , I Reading Room 1 READING GOD'S WORD: THE LEGTIONARY a National Bulletin on Liturgy A review published by the Canadian Catholic Conference Thls Bulletin is primarily pastoral in scope, and Is prepared for members of parish liturgy committees, readers, musicians, singers, teachers, religious and clergy, and all who are involved In preparing and celebrating the community liturgy. Editor REV. PATRICK BYRNE Editorial Office NATIONAL LITURGICAL OFFICE 90 Parent Avenue Ottawa, Ontario KIN 781 Business Office PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 90 Parent Avenue Ottawa, Ontario KIN 781 Published five times a year Appears every two months, except July and August Subscription: $6.00 a year; outside Canada. $8.00 Price per copy: $2.00; outside Canada. $2.50 Subscriptions available through Publications Service of the CCC, or through the chancery office in each diocese in Canada. National Bulletin on Liturgy, copyright @ Canadian Catholic Conference, 1975. No part of this Bulletin may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of CCC Publicatlons. International Standard Serial Number: CN ISSN 0084-8425. Legal deposit: Natlonal Library, Ottawa. Canada Second Class Mail - Registration Number 2994. national bulletin liturgy volume 8 number september-october 1975 READING GOD'S WORD: THE LECTIONARY The word of God has such an important place in the liturgy of the Church that we can tend to take it for granted, or see it only in terms of the daily set of readings. We often fail to realize that scripture - God's word to his beloved children - is the basis and foundation of the prayers we say, and the source of meaning for our acts and gestures.