Norethisterone.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suitability of Immobilized Systems for Microbiological Degradation of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds

molecules Review Suitability of Immobilized Systems for Microbiological Degradation of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds Danuta Wojcieszy ´nska , Ariel Marchlewicz and Urszula Guzik * Institute of Biology, Biotechnology and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Natural Science, University of Silesia in Katowice, Jagiello´nska28, 40-032 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (A.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-3220-095-67 Academic Editors: Urszula Guzik and Danuta Wojcieszy´nska Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 25 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: The rising pollution of the environment with endocrine disrupting compounds has increased interest in searching for new, effective bioremediation methods. Particular attention is paid to the search for microorganisms with high degradation potential and the possibility of their use in the degradation of endocrine disrupting compounds. Increasingly, immobilized microorganisms or enzymes are used in biodegradation systems. This review presents the main sources of endocrine disrupting compounds and identifies the risks associated with their presence in the environment. The main pathways of degradation of these compounds by microorganisms are also presented. The last part is devoted to an overview of the immobilization methods used for the purposes of enabling the use of biocatalysts in environmental bioremediation. Keywords: EDCs; hormones; degradation; immobilization; microorganisms 1. Introduction The development of modern tools for the separation and identification of chemical substances has drawn attention to the so-called micropollution of the environment. Many of these contaminants belong to the emergent pollutants class. According to the Stockholm Convention they are characterized by high persistence, are transported over long distances in the environment through water, accumulate in the tissue of living organisms and can adversely affect them [1]. -

SPIRONOLACTONE Spironolactone – Oral (Common Brand Name

SPIRONOLACTONE Spironolactone – oral (common brand name: Aldactone) Uses: Spironolactone is used to treat high blood pressure. Lowering high blood pressure helps prevent strokes, heart attacks, and kidney problems. It is also used to treat swelling (edema) caused by certain conditions (e.g., congestive heart failure) by removing excess fluid and improving symptoms such as breathing problems. This medication is also used to treat low potassium levels and conditions in which the body is making too much of a natural chemical (aldosterone). Spironolactone is known as a “water pill” (potassium-sparing diuretic). Other uses: This medication has also been used to treat acne in women, female pattern hair loss, and excessive hair growth (hirsutism), especially in women with polycystic ovary disease. Side effects: Drowsiness, lightheadedness, stomach upset, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or headache may occur. To minimize lightheadedness, get up slowly when rising from a seated or lying position. If any of these effects persist or worsen, notify your doctor promptly. Tell your doctor immediately if any of these unlikely but serious side effects occur; dizziness, increased thirst, change in the amount of urine, mental/mood chances, unusual fatigue/weakness, muscle spasms, menstrual period changes, sexual function problems. This medication may lead to high levels of potassium, especially in patients with kidney problems. If not treated, very high potassium levels can be fatal. Tell your doctor immediately if you notice any of the following unlikely but serious side effects: slow/irregular heartbeat, muscle weakness. Precautions: Before taking spironolactone, tell your doctor or pharmacist if you are allergic to it; or if you have any other allergies. -

Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals Carlotta Cocchetti 1, Jiska Ristori 1, Alessia Romani 1, Mario Maggi 2 and Alessandra Daphne Fisher 1,* 1 Andrology, Women’s Endocrinology and Gender Incongruence Unit, Florence University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (C.C); jiska.ristori@unifi.it (J.R.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Experimental, Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, Careggi University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected]fi.it * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Introduction: To date no standardized hormonal treatment protocols for non-binary transgender individuals have been described in the literature and there is a lack of data regarding their efficacy and safety. Objectives: To suggest possible treatment strategies for non-binary transgender individuals with non-standardized requests and to emphasize the importance of a personalized clinical approach. Methods: A narrative review of pertinent literature on gender-affirming hormonal treatment in transgender persons was performed using PubMed. Results: New hormonal treatment regimens outside those reported in current guidelines should be considered for non-binary transgender individuals, in order to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. In the present review we suggested the use of hormonal and non-hormonal compounds, which—based on their mechanism of action—could be used in these cases depending on clients’ requests. Conclusion: Requests for an individualized hormonal treatment in non-binary transgender individuals represent a future challenge for professionals managing transgender health care. For each case, clinicians should balance the benefits and risks of a personalized non-standardized treatment, actively involving the person in decisions regarding hormonal treatment. -

Pp375-430-Annex 1.Qxd

ANNEX 1 CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA ON COMPOUNDS USED IN COMBINED ESTROGEN–PROGESTOGEN CONTRACEPTIVES AND HORMONAL MENOPAUSAL THERAPY Annex 1 describes the chemical and physical data, technical products, trends in produc- tion by region and uses of estrogens and progestogens in combined estrogen–progestogen contraceptives and hormonal menopausal therapy. Estrogens and progestogens are listed separately in alphabetical order. Trade names for these compounds alone and in combination are given in Annexes 2–4. Sales are listed according to the regions designated by WHO. These are: Africa: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe America (North): Canada, Central America (Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Puerto Rico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago), United States of America America (South): Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, -

Exposure to Female Hormone Drugs During Pregnancy

British Journal of Cancer (1999) 80(7), 1092–1097 © 1999 Cancer Research Campaign Article no. bjoc.1998.0469 Exposure to female hormone drugs during pregnancy: effect on malformations and cancer E Hemminki, M Gissler and H Toukomaa National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health, Health Services Research Unit, PO Box 220, 00531 Helsinki, Finland Summary This study aimed to investigate whether the use of female sex hormone drugs during pregnancy is a risk factor for subsequent breast and other oestrogen-dependent cancers among mothers and their children and for genital malformations in the children. A retrospective cohort of 2052 hormone-drug exposed mothers, 2038 control mothers and their 4130 infants was collected from maternity centres in Helsinki from 1954 to 1963. Cancer cases were searched for in national registers through record linkage. Exposures were examined by the type of the drug (oestrogen, progestin only) and by timing (early in pregnancy, only late in pregnancy). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with regard to mothers’ cancer, either in total or in specified hormone-dependent cancers. The total number of malformations recorded, as well as malformations of the genitals in male infants, were higher among exposed children. The number of cancers among the offspring was small and none of the differences between groups were statistically significant. The study supports the hypothesis that oestrogen or progestin drug therapy during pregnancy causes malformations among children who were exposed in utero but does not support the hypothesis that it causes cancer later in life in the mother; the power to study cancers in offspring, however, was very low. -

Estrogen Actions Throughout the Brain

Estrogen Actions Throughout the Brain BRUCE MCEWEN Harold and Margaret Milliken Hatch Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York 10021 ABSTRACT Besides affecting the hypothalamus and other brain areas related to reproduction, ovarian steroids have widespread effects throughout the brain, on serotonin pathways, catecholaminergic neurons, and the basal forebrain cholinergic system as well as the hippocampal formation, a brain region involved in spatial and declarative memory. Thus, ovarian steroids have measurable effects on affective state as well as cognition, with implications for dementia. Two actions are discussed in this review; both appear to involve a combination of genomic and nongenomic actions of ovarian hormones. First, regulation of the serotonergic system appears to be linked to the presence of estrogen- and progestin-sensitive neurons in the midbrain raphe as well as possibly nongenomic actions in brain areas to which serotonin neurons project their axons. Second, ovarian hormones regulate synapse turnover in the CA1 region of the hippocampus during the 4- to 5-day estrous cycle of the female rat. Formation of new excitatory synapses is induced by estradiol and involves N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, whereas downregulation of these synapses involves intracellular progestin receptors. A new, rapid method of radioimmunocytochemistry has made possible the demonstration of synapse formation by labeling and quantifying the specific synaptic and dendritic molecules involved. Although NMDA receptor activation is required for synapse formation, inhibitory interneurons may play a pivotal role as they express nuclear estrogen receptor-alpha (ER␣). It is also likely that estrogens may locally regulate events at the sites of synaptic contact in the excitatory pyramidal neurons where the synapses form. -

State of the Science Report | 19Th Annual PCF Scientific Retreat 2 Session 9 the Good, the Bad and the Ugly of Preclinical and Observational Research

STATE OF Highlights from the 19th Annual PCF THE SCIENCE Scientific Retreat REPORT October 2012 Provided with the compliments of the Prostate Cancer Foundation Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Special lecture Tumor Heterogeneity: Clonality and Consequences ..................................................................... 5 Session 1 Field Cancerization & the Tumor Microenvironment ..................................................................... 7 Special Lecture Cancer Interception & Metabolic Transformation ........................................................................ 10 Session 2 Role of Growth Factor and Signal Transduction Alterations in Prostate Cancer Initiation, Progression and Therapy Resistance .......................................................................................................... 12 Session 3 Advances in Molecular Imaging of Prostate Cancer .................................................................... 17 Breakthrough Lecture Organoids: A Profound New Prostate Cancer Model System ........................................................ 23 PCF-StandUpToCancer Dream Team Overview 1 ............................................................... 25 PCF-StandUpToCancer Dream Team Overview 2 ............................................................... 28 Exceptional Progress Report – PCF Young Investigator Integrated Molecular Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells: -

Guidelines for the Management of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

i GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HEAVY MENSTRUAL BLEEDING Prepared by a Working Party on behalf of the National Health Committee ii MAY 1998 Women reporting with heavy menstrual bleeding 50% of women have menstrual blood loss Full menstrual history ● Examination ● Full blood count note1 Yes Prolonged irregular cycles No Refer Yes Abnormal exam specialist uterine size >12wks note 2 No mild or severe anaemic moderate treat < 80 g/l (80-115g/l) anaemia No Assess risk of endometrial hyperplasia low Offer medical therapy ● risk Unexplaine bodyweight 90kg heavy menstrual ● note5 note 6 age 45 years <2% bleeding ● other risk factors have 90% of women note 3 ● levonorgestrel endometrial >8% have hyperplasia intrauterine system ● tranexamic acid ● Assess endometrium nonsteroidal ● transvaginal ultrasound antiinflammatory agents ● (TVS) norethisterone long course or normal ● oc pill endometrium ● ● endometrial biopsy if danazol if one medical therapyfails endometrium 12mm others can be used note 7 or if TVS not available note 4 Treatment Hyperplastic endometrium success? or carcinoma No Yes Refer to specialist for hysteroscopic evaluation Continue Refer specialist me d i c a l for surgery therapy note8 note9 iii note 1 O In women <20 years old pelvic examination is unlikely to contribute to management of heavy bleeding (C) and the likelihood of pathology is small (C) O Increased likelihood (70%) of heavy menstrual blood loss >80mls/cycle if Hb <120g/l (A) O Consider pictorial blood loss assessment charts (appendix 6.5) for women with normal -

Pharmacology on Your Palms CLASSIFICATION of the DRUGS

Pharmacology on your palms CLASSIFICATION OF THE DRUGS DRUGS FROM DRUGS AFFECTING THE ORGANS CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC DIFFERENT DRUGS AFFECTING THE NERVOUS SYSTEM AND TISSUES DRUGS PHARMACOLOGICAL GROUPS Drugs affecting peripheral Antitumor drugs Drugs affecting the cardiovascular Antimicrobial, antiviral, Drugs affecting the nervous system Antiallergic drugs system antiparasitic drugs central nervous system Drugs affecting the sensory Antidotes nerve endings Cardiac glycosides Antibiotics CNS DEPRESSANTS (AFFECTING THE Antihypertensive drugs Sulfonamides Analgesics (opioid, AFFERENT INNERVATION) Antianginal drugs Antituberculous drugs analgesics-antipyretics, Antiarrhythmic drugs Antihelminthic drugs NSAIDs) Local anaesthetics Antihyperlipidemic drugs Antifungal drugs Sedative and hypnotic Coating drugs Spasmolytics Antiviral drugs drugs Adsorbents Drugs affecting the excretory system Antimalarial drugs Tranquilizers Astringents Diuretics Antisyphilitic drugs Neuroleptics Expectorants Drugs affecting the hemopoietic system Antiseptics Anticonvulsants Irritant drugs Drugs affecting blood coagulation Disinfectants Antiparkinsonian drugs Drugs affecting peripheral Drugs affecting erythro- and leukopoiesis General anaesthetics neurotransmitter processes Drugs affecting the digestive system CNS STIMULANTS (AFFECTING THE Anorectic drugs Psychomotor stimulants EFFERENT PART OF THE Bitter stuffs. Drugs for replacement therapy Analeptics NERVOUS SYSTEM) Antiacid drugs Antidepressants Direct-acting-cholinomimetics Antiulcer drugs Nootropics (Cognitive -

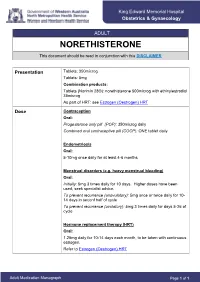

NORETHISTERONE This Document Should Be Read in Conjunction with This DISCLAIMER

King Edward Memorial Hospital Obstetrics & Gynaecology ADULT NORETHISTERONE This document should be read in conjunction with this DISCLAIMER Presentation Tablets: 350microg Tablets: 5mg Combination products: Tablets (Norimin 28®): norethisterone 500microg with ethinylestradiol 35microg As part of HRT: see Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Dose Contraception Oral: Progesterone only pill (POP): 350microg daily Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP): ONE tablet daily Endometriosis Oral: 5-10mg once daily for at least 4-6 months Menstrual disorders (e.g. heavy menstrual bleeding) Oral: Initially: 5mg 3 times daily for 10 days. Higher doses have been used; seek specialist advice. To prevent recurrence (anovulatory): 5mg once or twice daily for 10- 14 days in seconf half of cycle To prevent recurrence (ovulatory): 5mg 3 times daily for days 5-26 of cycle Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) Oral: 1.25mg daily for 10-14 days each month, to be taken with continuous estrogen. Refer to Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Adult Medication Monograph Page 1 of 1 Norethisterone – Adult Administration Oral To be taken at the same time each day (or within 3 hours of the usual dose time). For Contraception: Start 4 weeks after the birth of baby (increased risk of abnormal vaginal bleeding if started earlier) Pregnancy 1st Trimester: Contraindicated 2nd Trimester: Contraindicated 3rd Trimester: Contraindicated Breastfeeding Considered safe to use. Progestogens are the preferred hormonal contraceptives as they do not inhibit lactation. Clinical Guidelines Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT and Policies Progesterone Only Pill Contraception: Post Partum Gynaecology (Non-Oncological) Australian Medicines Handbook. Norethisterone. In: Australian References Medicines Handbook [Internet]. Adelaide (South Australia): Australian Medicines Handbook; 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. -

Nur-Isterate Injection

SELECT THE REQUIRED INFORMATION PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION LEAFLET SCHEDULING STATUS: S4 PROPRIETARY NAME AND DOSAGE FORM: NUR-ISTERATE Oily solution for intramuscular injection COMPOSITION: 1 ml contains norethisterone enantate (17-ethinyl-17-heptanoyloxy-4-estrene-3-one) 200 mg. Other ingredients are: benzyl benzoate, castor oil for injection. PHARMACOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION: A. 21.8.2 Progesterones without estrogens. PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTION: Pharmacodynamic properties: Protection against conception is based primarily upon an alteration of the cervical mucous. This alteration is present for the whole of the duration of action and prevents the ascent of the sperm into the uterine cavity. Radioimmunological studies have shown that, during the first 5 to 7 weeks after injection, ovulation is suppressed as a result of the high plasma level of norethisterone. In addition, NUR- ISTERATE causes morphological changes in the endometrium which have the effect of rendering nidation of a fertilised egg difficult. Pharmacokinetic properties: Norethisterone enantate was completely absorbed after intramuscular injection. The ester was eventually completely hydrolysed to its pharmacologically active compound norethisterone once it was released from the depot. Maximum levels of norethisterone were measured at about 3 to 10 days after IM administration. They amounted on average to 13.4 5.4 ng/ml and 12.2 2.7 ng/ml about 7 days (median) after IM administration of 200 mg norethisterone enantate in 2 ml and 1 ml oily solution, respectively. Plasma levels of norethisterone declined in two disposition phases with half-lives of 4 to 5 days and 15 to 20 days, respectively, which were due to a biphasic release of norethisterone enantate from the depot. -

Illinois Medicaid Preferred Drug List

Illinois Medicaid Preferred Drug List Effective January 1, 2020 (Updated January 27, 2020) ▪ The Preferred Drug List (PDL) has products listed in groups by drug class, drug name, dosage form, and PDL status ▪ Multi-source drugs are listed by both brand and generic names when applicable ▪ ADHD Agents: Prior authorization required for participants under 6 years of age and participants 19 years of age and older ▪ Spiriva AER 1.25mcg: Prior authorization NOT required for participants ages 6-17 years ▪ Budesonide: Prior authorization NOT required for participants age 7 years and under ▪ Anticonvulsants: Prior authorization NOT required for non-preferred epilepsy agents for those participants with a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizure disorder in Department records ▪ Antipsychotics: Prior authorization required for participants under 8 years of age and long-term care residents ▪ For drugs not found on this list, go to the drug search engine at: www.ilpriorauth.com Page 1 of 92 DOSAGE DRUG CLASS DRUG NAME PDL STATS FORM ADHD / ANTI-NARCOLEPSY AGENTS : AMPHETAMINES ADZENYS ER SUER NON_PREFERRED AMPHETAMINE ER SUER NON_PREFERRED DYANAVEL XR SUER NON_PREFERRED ADZENYS XR-ODT TBED NON_PREFERRED AMPHETAMINE SULFATE TABS NON_PREFERRED EVEKEO TABS NON_PREFERRED EVEKEO ODT TBDP NON_PREFERRED DEXEDRINE CP24 NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE ER CP24 NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE SOLN NON_PREFERRED PROCENTRA SOLN NON_PREFERRED DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE TABS NON_PREFERRED ZENZEDI TABS NON_PREFERRED VYVANSE CAPS PREFERRED VYVANSE CHEW PREFERRED