Iii) Related and Foreign Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

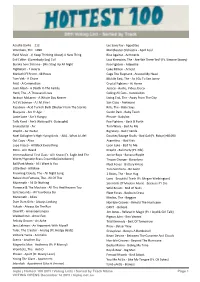

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Words With...Mugstar

CABLE #7 THIS ISSUE: CONTRIBUTE: Mugstar Apposing Send your news stories to: Pacificstream Elevator’s Christmas Party [email protected] The Wombats Smiling Wolf Follow us on: Bendal Interlude www.twitter.com/elevatorstudios Miles Kane or www.facebook.com/elevatorstudios WORDS WITH...MUGSTAR Mugstar’s stats are impressive. Achievements in Mogwai and Wooden Shjips, signing to Important work out. Working with Rob Whitely, in White- 2010 alone stand at 2 albums, 1 single, 3 UK tours, Records and we will have some very exciting news wood Studios, has had a massive impact on this ap- 1 European tour, and 1 film credit. They’re listed in shortly, which will be a massive highlight.” proach and he has actively encouraged this. 5 top 50 albums of the year lists and appear at num- ber 6 in the NME’s top 10 noise rock bands. To say Do Mugstar feel the John Peel connection played “The reception to ‘Lime’ has been unbelievable. It’s they’ve put in the hours is a horrendous disservice an important part in their success? “By having John been called the ‘best space rock album of 2010’. to the work load they’ve undertaken. All this and Peel play our music he opened a lot of doors for us. We recently had a great review in Mojo magazine producing the best material of their lives? Though But for ourselves he somewhat validated what we and in a number of magazines in the States. We’ve they’ve been together 8 years, it seems Mugstar were doing at the time, making you realise you must had more press than ever before, so it’s been a very are just getting positive release started.. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Rock & Pop 2015-2017.Indd

2015–2017 SYLLABUS EXAMS Bass Drums Guitar Keyboards Vocals 2015–2017 SYLLABUS EXAMS Bass Drums Guitar Keyboards Vocals Trinity College London is an awarding body recognised by the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) in England and Northern Ireland, and by Qualifications Wales (QW). Trinity’s qualifications are regulated by these authorities within the Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF). Various arrangements are in place with governmental education authorities worldwide. Trinity College London’s Rock & Pop syllabus and supporting publications have been devised and produced in association with Faber Music and Peters Edition London. Trinity College London www.trinitycollege.com Charity number 1014792 Patron HRH The Duke of Kent KG Chief Executive Sarah Kemp Copyright © 2014 Trinity College London Published by Trinity College London Second impression, April 2016 Contents Introduction ..........................................................4 Range of qualifications .......................................5 Exams at a glance .............................................. 6 How the exams are marked................................ 7 About the exams ................................................. 9 Group exams ..................................................... 10 Choosing songs .................................................12 Session skills ....................................................... 14 Bass .....................................................................15 Songbook lists ..........................................16 -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Semantic Audio Analysis Utilities and Applications

Semantic Audio Analysis Utilities and Applications PhD Thesis Gyorgy¨ Fazekas Centre for Digital Music School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science, Queen Mary University of London April 2012 I certify that this thesis, and the research to which it refers, are the product of my own work, and that any ideas or quotations from the work of other people, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices of the discipline. I acknowledge the helpful guidance and support of my supervisor, Professor Mark Sandler. Abstract Extraction, representation, organisation and application of metadata about audio recordings are in the concern of semantic audio analysis. Our broad interpretation, aligned with re- cent developments in the field, includes methodological aspects of semantic audio, such as those related to information management, knowledge representation and applications of the extracted information. In particular, we look at how Semantic Web technologies may be used to enhance information management practices in two audio related areas: music informatics and music production. In the first area, we are concerned with music information retrieval (MIR) and related research. We examine how structured data may be used to support reproducibility and provenance of extracted information, and aim to support multi-modality and context adap- tation in the analysis. In creative music production, our goals can be summarised as follows: O↵-the-shelf sound editors do not hold appropriately structured information about the edited material, thus human-computer interaction is inefficient. We believe that recent developments in sound analysis and music understanding are capable of bringing about significant improve- ments in the music production workflow. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

The Election Countdown Has Begun

ISSUE 12 (192) • 24 – 30 MARCH 2011 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI DOMESTIC INTERNATIONAL LIFESTYLE CULTURE EAT & DRINK Babies Air war Time The return Café idyll napping on to get of the in outside Libya a tattoo? Prince Kallio page 3 page 9 page 14 page 15 page 16 LEHTIKUVA / ANTTI AIMO-KOIVISTO World Bank and Moody’s have faith in Japanese economy HEIKKI KARKKOLAINEN – STT Monday, however, Moody’s said MATTHEW PARRY – HT the government has the fi scal and credit resources to deal with the ACCORDING to a number of esti- catastrophe. mates, the destruction caused by Japan’s Minister for Economic the earthquake and tsunami that and Fiscal Policy Kaoru Yosano es- struck Japan earlier this month is timated last week that the materi- more than twice as great as the ma- al damage caused by the earthquake terial losses suffered during the Ko- and the tsunami would rise to 250 be earthquake in 1995. billion US dollars or around 177 bil- The World Bank and credit rating lion euros. Many economists’ esti- agency Moody’s believe the effects mates were around the 200 billion will be short-term, however. Moody’s US dollar mark. Japanese media re- is convinced that the Japanese state port that the government plans to is able to absorb the economic blow. lend up to 122 billion US dollars to But the credit rating agency adds companies for daily expenses or The leaders of Finland’s eight biggest political parties participated in a televised debate organised by the Finnish Broad- that the risks have increased. -

Miles Kane Releases Debut Solo Single Claudia Pink's X

CABLE #6 THIS ISSUE: CONTRIBUTE: Miles Kane Milky Tea Send your news stories to: Claudia Pink Studio Liverpool [email protected] Wombats Owls* Follow us on: Bicycle Thieves In The Room Print Company www.twitter.com/elevatorstudios Mugstar Ditto Music or www.facebook.com/elevatorstudios MILES KANE RELEASES DEBUT SOLO SINGLE Last Shadow Puppet and former Rascals front- man Miles Kane has released his first solo single, ‘Inhaler’ after completing a short tour of the UK. With support from friends and fellow Elevator band, Bi- cycle Thieves, Miles took his highly anticipated material on the road. After performing a free gig at Liverpool Music Week, the tour culminated in Kane’s first lone London date at The Water Rats. ‘Inhaler’ was released on November 22nd on Columbia re- cords and is a tribute to Los Angeles’ psychedelic garage group Bonniwell Music Machine - ‘Inhaler’ is an adapta- tion of their 1969 track ‘Mother Nature Father Earth’. “I loved the guitar riff on ‘Mother Nature Father Earth’,” explains Miles. “It’s got a real groove to it and this riff inspired me to build a song around it which then became ‘Inhaler’.” The b-side features a cover version of another of Miles’ vin- tage influences, a dazzling take on Lee Hazlewood’s psych- pop classic, ‘Rainbow Woman’. The record is available as a limited edition 7” vinyl single and includes a special poster. The track will also be avail- able as a digital download. Miles has announced details of a full UK tour in January and March, and will be playing at the Sound City 2011 Launch Party Miles Kane on February 25th at the Kazimier. -

Oink, Mnemotechnics and the Private Bittorrent Architecture

Digital desire and recorded music: OiNK, mnemotechnics and the private BitTorrent architecture Andrew Sockanathan PhD Thesis Goldsmiths College Centre for Cultural Studies 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own ___________________ Andrew Sockanathan 2 Abstract This thesis centres on the P2P internet protocol BitTorrent, music filesharing, and nascent forms of collective action developing through private BitTorrent communities. The focus is on one of these communities, a music filesharing website called ‘OiNK’. Founded in 2005, it was the first of its kind to garner membership in the hundreds of thousands, was emblematic of user-led movements to improve the quality, efficiency and availability of digital media online, and was very publically shut down in 2007. Making critical use of Simondon’s notion of ‘individuation’, two interrelated techno- historical impulses are identified as central to the ‘in-formation’ of both BitTorrent and OiNK. Firstly, through research into the development of the global music industry’s ‘productive circuit’ of manufacturing, distribution, retail and radio, it is shown how consumers were gradually excluded from having a say in how, what and where they could consume. Secondly, a history of ‘OiNK-style’ filesharing is gleaned, not from P2P, but from research into small, decentralised ‘online’ communities that emerged throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, where enthusiasts learned how to use software and hardware to manage the storage, reproduction, uploading and sharing of information. This thesis shows how BitTorrent exposed these previously exclusive practices to masses of consumers who were dissatisfied with both retail/broadcasting and public P2P, through the new possibility of private BitTorrent communities.