IN MEDIA RES Why Multimedia Performance?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

Ahmanson Theatre

AHMANSON THEATRE 1967-68 PREMIERE SEASON 1968-69 SEASON “More Stately Mansions” “Captain Brassbound’s Conversion” by Eugene O’Neill; by George Bernard Shaw; Starring Ingrid Bergman, Arthur Hill Starring Greer Garson, and Colleen Dewhurst; Darren McGavin, Jim Backus, Paul Directed by José Quintero. Ford, John Williams, George Rose (American Premiere). and Tony Tanner; September 12 - October 21, 1967. Directed by Joseph Anthony. “The Happy Time” September 24 - November 9, 1968. Book by N. Richard Nash; “Love Match” Based on the play by Samuel A. Book by Christian Hamilton; Taylor and the book by Robert L. Music by David Shire; Fontaine; Music by John Kander; Lyrics by Richard Maltby Jr.; Lyrics by Fred Ebb; Starring Patricia Routledge, Starring Robert Goulet and Michael Allinson and Hal Linden; David Wayne; Directed and choreographed by Directed and choreographed by Danny Daniels. Gower Champion. (World Premiere). (World Premiere). November 19, 1968 - January 4, 1969. November 13 - December 23, 1967. The Royal Shakespeare Company in The Royal Shakespeare Company in “Dr. Faustus” “As You Like It” by Christopher Marlowe; by William Shakespeare; Directed by Clifford Williams. Directed by David Jones. “Much Ado About Nothing” “The Taming of the Shrew” by William Shakespeare; by William Shakespeare; Directed by Trevor Nunn. Directed by Trevor Nunn. January 14 - March 1, 1969. January 2 - February 10, 1968. “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” “Catch My Soul” by Tom Stoppard; Words by William Shakespeare; Starring Brian Murray and Music by Ray Pohlman; George Backman; Starring William Marshall, Jerry Lee Directed by Derek Goldby. Lewis and Julienne Marie; March 11 - April 26, 1969. -

Copy of Kelly Devine Template.Indd

THE COOPER COMPANY A Production and Artist Representation Group KELLY DEVINE page 1 of 2 choreographer BROADWAY/INTERNATIONAL Zhivago (upcoming) choreographer dir. Des McAnuff/Broadway Theatre resumé Bliss: A New Musical (upcoming) director/choreographer Jawbreaker (upcoming) director/choreographer Come From Away (upcoming) choreographer dir. Chris Ashley Nobody Loves You (upcoming) choreographer dir. Pam Mckinnon Rocky choreographer dir. Alex Timbers/Germany/Up- coming on Broadway Zhivago choreographer dir. Des McAnuff/Lyric Theatre REPRESENTATION (Helpmann Award nom. Best Choreo) Sydney/Her Majesty’s Theatre Melbourne/ Lyric Theatre Bris- WME bane/OD Musicals Korea Susan Weaving Rock of Ages choreographer London/Shaftesbury Theatre Phone: (212) 903-1170 Rock of Ages choreographer Melbourne/Comedy Theatre (Green Room Award, Best Choreo Helpmann Award, Best Choreo) Faust choreographer dir. Des McAnuff/ English National Opera Rock of Ages choreographer Royal Alexandra Theatre/ MANAGEMENT (Dora Award nom.) Toronto The Cooper Company Memphis assoc. choreographer dir. Chris Ashley Phone: (212) 904-1000 (Tony Award, Best Musical) Rock of Ages choreographer dir. Kristin Hanggi/ Helen Hayes/Brooks Atkinson Theatre Cabaret choreographer Stratford Festival in Canada Romeo & Juliet choreographer Stratford Festival in Canada Jersey Boys asst. choreographer dir. Des McAnuff (Tony Award, Best Musical) - OFF-BROADWAY/ - TOURS/REGIONAL Getting the Band Back Together choreographer dir. John Rando/George St. Rock of Ages choreographer Las Vegas/The Venetian Fat Camp choreographer dir. Casey Hushion Toxic Avenger choreographer dir. John Rando/ The Alley Theatre Rock of Ages choreographer dir. Kristin Hanggi/ 1st National Tour A Christmas Story choreographer dir. Eric Rosen/ 5th Avenue Theatre Peter and the Starcatcher choreographer dir. Alex Timbers/Roger Rees La Jolla Playhouse A Christmas Story choreographer dir. -

THE BROADWAY PRINCESS PARTY The

THE BROADWAY PRINCESS PARTY The princesses are throwing a ball, and you’re invited! After five sold-out engagements in New York City, The Broadway Princess Party is coming to the Segerstorm Center for the Arts! Star of Broadway’s Cinderella, two time Tony nominee, Laura Osnes will bring her radiant leading lady friends to Orange County along with music director Benjamin Rauhala for a dazzling evening of musical magic. She will be joined by Broadway’s 'Princess Jasmine' in Aladdin Courtney Reed, and Tony nominee Adrienne Warren to sing the most beloved ‘Princess’ songs of stage and screen and reminisce about their favorite fairytales and most cherished characters. So get your ballgown out of the closet, dust off that tiara and make your way to the Segerstorm Center for the Arts for a Broadway Princess Party you will never forget! The concerts are presented by LML Music and produced by Integrated Arts, LLC. Laura Osnes will return to Broadway this spring in the new musical Bandstand after creating the role of Julia Trojan in the Paper Mill Playhouse production. Her other Broadway credits include the title role in Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella (Drama Desk Award; Tony, Outer Critics Circle, Drama League and Astaire Award nominations), Bonnie in Bonnie and Clyde (Tony Award nomination), Hope Harcourt in the Tony Award winning revival of Anything Goes (Drama Desk, Outer Critics Circle, and Astaire Award nominations), Nellie Forbush in Lincoln Center Theater’s production of South Pacific, and Sandy in the most recent revival of Grease. Other New York/regional credits include The Blueprint Specials, The Threepenny Opera (Drama Desk Award nomination) at the Atlantic Theater Company; City Center Encores! productions of The Band Wagon, Randy Newman's Faust, and Pipe Dream; The Sound of Music in concert at Carnegie Hall; Carousel opposite Steven Pasquale at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Broadway: Three Generations at the Kennedy Center. -

1 “Old Hickory Just Got All Sexypants: History and Politics in Bloody

“Old Hickory Just Got All Sexypants: History and Politics in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson” INTRODUCTION In the fall of 2010, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson (BBAJ) debuted on Broadway. This theatrical production, co-written by Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman, with music by Friedman, experienced a 120-show run from October 2010 through January 2011.1 The play gave Jackson a prominent role in a dramatic production, something that he has rarely received.2 This paper examines the soundtrack, evaluating the song lyrics for their historical accuracy and interpretation of Jackson and the period named for him. SUMMARY3 The soundtrack begins with the upbeat “Populism, Yea, Yea!” This anthem of the disenchanted, disenfranchised lower classes is filtered through Jackson’s teenage angst. The lyrics suggest that Jackson sought validation through populist politics to soothe the rejection he faced as an adolescent. His despondency continues in “I’m Not That Guy,” which highlights Jackson’s despair as someone left without a family. He transfers the blame for his life “suck”ing from his orphanhood to “[t]hose wealthy New 1 The show premiered in Los Angeles in January 2008 and opened in the Public Theater in New York in May 2009. Les Freres Corbusier, “Repertory Archives,” http://www.lesfreres.org/archives/06_jackson.html; accessed 13 April 2012. 2 Jackson has “starred” in only one full-length movie: The President’s Lady (1953). He played prominent roles in The Buccaneer (1938) and The Remarkable Andrew (1942). On TV shows, his most high-profile appearance was in “Jackson’s Assassination,” a season one episode of The Adventures of Jim Bowie (1957). -

JACOB DANIEL PINHOLSTER CV Academic Master

JACOB DANIEL PINHOLSTER, Associate Dean and Associate Professor Curriculum Vitae PO Box 872002 W: 480.965.2696 Tempe, AZ 85287-2002 F: 480.965.5351 [email protected] EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts in Scenic & Lighting Design: May 2003 University of Florida, Department of Theatre and Dance Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theatre Production: May 2000, cum Laude University of Florida, Department of Theatre and Dance PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2016 - Arizona State University, Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, Associate Dean for Policy and Initiatives 2013 – 2016 Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Film, Dance and Theatre, Director and Producer 2012 – 2013 Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Dance, Interim Director 2012 – present Arizona State University, Barrett the Honors College, Honors Faculty 2011 – 2013 Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Theatre and Film, Director and Artistic Director 2010 – 2011 Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Theatre and Film, Associate Director and Director of Undergraduate Study 2005 – present Arizona State University, Herberger Institute School of Theatre and Film, Associate Professor of Performance Design 2005 - present Arizona State University, School of Arts, Media & Engineering, affiliate faculty 2005 – present Les Freres Corbusieri, Associate Artist 2007 – present Mental Image Design, Principal designer, design and consulting firm 2004 - 2005 Scharff-Weisberg Staging & Pro Audio, Programmer, technician – freelance 2004 MTV Networks: Special Events, Design assistant: freelance 2003 Williamstown Theatre Festivalii, Assistant scenic designer 2002 - 2003 Central Florida Community College, Associate instructor: Scene Painting GRANTS, HONORS AND AWARDS External Grants Andrew W. Mellon Foundation: Projecting All Voices. Investigator and lead proposal author on grant to improve early career development and post-secondary outcomes for artists and designers who are under-represented in their fields. -

2008 Next BAM Endowment Trust Wave Festival

BAMAnnual2oo6—2oo8 MUSIC, THEATER, FILM, COmmUNITY, ART, DANCE Brooklyn, New York Since 1861 2 BAM Chair Letter 4 President & Exec. Producer Letter 6 2006 Next Wave Festival 8 2007 Next Wave Festival 10 BAM Dance 12 BAM Music/Opera 14 BAM Theater 16 BAM Rose Cinemas BAMcinématek 20 Sundance Institute at BAM 21 Takeover 22 Between the Lines 23 The Met: Live in HD 24 BAMart 26 BAMcafé Live 30 Community 32 Education 34 Humanities 38 Hamm Archives 40 BAM Next Stage Campaign 50 Staff 52 Mission Statement 53 Board 62 Financial Statements Amjad, 2008 Next BAM ENDOWMENT TRUST Wave Festival. A-1 BET Chair Letter Photo courtesy Édouard Lock A-3 BET Mission Statement A-4 BET Board A-5 BET Financial Statements Alan H. Fishman To the BAM family: The past two performance seasons once In 2007, major milestone anniversaries Building. This building will be a much- valued leadership. I welcome the new again demonstrated the excellence of were celebrated by two of our anchor needed facility used to introduce emerging members who have joined since July BAM’s programming and the family of programs: the Next Wave Festival and artists to our audience as well as expand 2006: Linda Chinn, William Edwards, artists, patrons, audiences, and staff DanceAfrica. The Next Wave Festival our community and arts education pro- Richard Feldman, Derek Jenkins, Gary whose dedication and effort make it all celebrated its 25th season and its 25th grams. I encourage all of you to join me in Lynch, Donald R. Mullen, Jr., Brian Nigito, possible. The achievements delineated on consecutive year of sponsorship and part- supporting this landmark fundraising effort Steven Sachs, Timothy Sebunya, Jessica the following pages would not be possible nership from Altria Group, Inc. -

2016Fallpreview Final.Pdf

THEATRE BAY AREA 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS San Francisco - p. 1 East Bay - p. 9 South Bay - p. 15 North Bay - p. 20 Beyond the Bay - p. 23 World Premiere Children’s Show SAN FRANCISCO 3Girls Theatre Company 13th Floor Z Below 470 Florida St. Joe Goode Annex Entanglement 401 Alabama St. (By AJ Baker; dir. Louis Parnell) 11/17-12/17 Next Time, I’ll Take the Stairs 12/8-18 42nd Street Moon Eureka Theatre 215 Jackson St. Marines’ Memorial Theatre 609 Sutter St. Baker Street Rotimi Agbabiaka in Brava Theatre (By M. Grudeff, R. Jessel & J. Coopersmith; Center’s production of Type/Caste. Photo: Shot in the City Eureka Theatre 11/2-20 The Hard Problem Described in the press as “Brilliantly (By Tom Stoppard; dir. Carey Perloff) written and choreographed, often Scrooge in Love 10/19-11/13 brain-achingly funny, this Alice and (By L. Grossman, K. Blair & D. Poole; dir. Wonderland journey is a whirlwind of Dyan McBride & Dave Dobrusky) A Christmas Carol mischievous non sequiturs - marvelous Marines’ Memorial Theatre (By Carey Perloff & Paul Walsh; adptd. and memorable.” Next Time, I’ll Take 12/7-24 from Charles Dickens; dir. Domenique The Stairs follows the multi-storied Lozano) adventures of Otis, Ivy, Norris, Arthur 11/25-12/24 and Rabbit as they tumble down the American Conservatory Theater elevator shaft into a world where down A Thousand Splendid Suns is up, up is nowhere, and long-forgotten Geary Theater (By Ursula Rani Sarma; adptd. from childhood monsters are waiting with 415 Geary St. Khaled Hosseini; dir. -

Wagner College Theatre Celebrates 50Th Anniversary Throughout 2018

December 18, 2017 Wagner College Theatre celebrates 50th anniversary throughout 2018 The award-winning Wagner College Theatre Department is celebrating its golden jubilee throughout 2018 with a year of exciting events. The WCT was founded in 1968 by Lowell Matson; thus began a 50-year history of producing theatre for the Staten Island community. Alumni of the Wagner College Theatre include Betsy Joslyn, Randy Graff, Janine LaManna and Kathy Brier along with a current generation working on shows like “Dear Evan Hansen,” “Hello, Dolly!”, “The Book of Mormon,” “Jersey Boys” and the Radio City Rockettes. Department chairs who have continued the WCT tradition of excellence are Gary Sullivan, Lewis Hardee, Christopher Catt and Felicia Ruff. “Onstage and off, we take pride in our alumni,” said Ruff. “The 50th anniversary allows us to celebrate their amazing contributions to the great American export — entertainment! — as well as dedicating ourselves to another 50 years service to the performing arts.” Wagner College Theatre has devoted itself to live performance, particularly musical theater, since its founding in 1968. Many schools have recently founded programs that capitalize on the popularity of musicals, but Wagner’s Theatre Department has been taking this intrinsically American form seriously for 50 years. Undergraduates study dance, acting, music, design, management, directing and more, all in a liberal arts setting. On our Main Stage as well as in the WCT’s Stage One studio theater, students and audiences love coming together for live performances of new works as well as classics. The Wagner College Theatre Department will celebrate its 50th anniversary throughout 2018. -

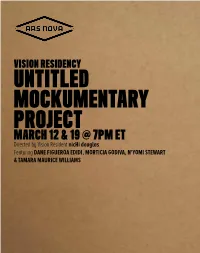

Mockumentary Project

VISION RESIDENCY UNTITLED MOCKUMENTARY PROJECT MARCH 12 & 19 @ 7PM ET Directed by Vision Resident nicHi douglas Featuring DANE FIGUEROA EDIDI, MORTICIA GODIVA, N'YOMI STEWART & TAMARA MAURICE WILLIAMS UNTITLED MOCKUMENTARY PROJECT EPISODES 1 & 2: MARCH 12 @ 7PM ET EPISODES 3 & 4: MARCH 19 @ 7 PM ET THE TEAM Directed by Vision Resident nicHi douglas Written & Performed by DANE FIGUEROA EDIDI, MORTICIA GODIVA, N'YOMI STEWART & TAMARA MAURICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography ADELE OVERBEY Co-Composers TROY ANTHONY & GABBY HENDERSON Music TROY ANTHONY Sound TERESA-ESMERALDA SANCHEZ Gaffer MARLEY CHAPMAN Producer ASHTON MUÑIZ Assistant Director AVA ELIZABETH NOVAK Production Manager & Community Engagement MELISSA MOWRY Production Assistant/Key Grip GALEN POWELL Music for Episode 4 Features the Song "Because of Love" Music & Lyrics GABBY HENDERSON Singer GABBY HENDERSON THE ARTISTS WOULD LIKE TO THANK All of Our Trans Sistren & Kin The World Over - Past, Present & Afro-Future Ars Nova operates on the unceded land of the Lenape peoples on the island of Manhahtaan (Mannahatta) in Lenapehoking, the Lenape Homeland. We acknowledge the brutal history of this stolen land and the displacement and dispossession of its Indigenous people. We also acknowledge that after there were stolen lands, there were stolen people. We honor the generations of displaced and enslaved people that built, and continue to build, the country that we occupy today. We gathered together in virtual space to watch this performance. We encourage you to consider the legacies of colonization embedded within the technology and structures we use and to acknowledge its disproportionate impact on communities of color and Indigenous peoples worldwide. -

A BRIEF HISTORY 1974-2020 a THESIS in Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansa

THE UNICORN THEATRE: A BRIEF HISTORY 1974-2020 A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by SARAH JEAN HAYNES-HOHNE B.F.A., Missouri State University, 2013 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 SARAH JEAN HAYNES-HOHNE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE UNICORN THEATRE: A BRIEF HISTORY 1974-2020 Sarah Jean Haynes-Hohne, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT The Unicorn Theatre was originally founded under the name Theatre Workshop in 1974. It was a theatre company formed by three UMKC graduates, Jim Cairns, Rohn Dennis, and Liz Gordon who wanted to create an Off-Off-Broadway theatre in Kansas City. Their work focused on experimentation and using theatre as a political statement for social change. For years, the theatre operated as a community of people who wore many hats and performed many functions. In some ways, this still remains true. However, the theatre made a significant shift in its goals and future when they joined Actors’ Equity Association in 1984 shortly after Cynthia Levin was named Producing Artistic Director. The company has operated out of four different locations over the past 45+ years, but it has been in its current location at 3828 Main Street, Kansas City, MO since 1986. Many expansions and financial campaigns have contributed to the success of the theatre, which now houses two stages, The Levin Stage and The Jerome Stage. The Unicorn Theatre now operates under the vision of producing “Bold New Plays” and thrives on a mission that revolves around inclusion and diversity. -

Gabriel Greene Gabriel Greene

Gabriel Greene Writing Experience Safe at Home (co-created with Alex Levy) Mixed Blood Theatre, Minneapolis, MN (world premiere; dir. Jack Reuler), March 2017 La Jolla Playhouse, La Jolla, CA (reading; dir. Alex Levy), February 2016 Goosebumps Alive (co-written with Tom Salamon) The Vaults, London (world premiere; dir. Tom Salamon), April 2016 Administrative Experience La Jolla Playhouse (La Jolla, CA) – Director of New Play Development September 2007 – Present Currently reports to the Artistic Director as a member of the Playhouse’s senior staff. The Playhouse’s six- show subscription season is complemented by its Page-to-Stage workshop productions, its annual POP Tour for elementary school audiences, its Without Walls (WoW) series of site-based works and its annual DNA New Work Series. Promoted from Literary Manager to Literary Director (senior staff) in May 2011, and to Director of New Play Development in April 2013. Steppenwolf Theatre Company (Chicago, IL) – Literary Manager April 2003 – September 2007 Worked under the Director of New Play Development, managing the day-to-day operations of the literary department. Steppenwolf programs between 10-12 plays per season on three stages, of which roughly half are new works. Promoted from Literary Assistant to Literary Manager in September 2005. The Mercury Theater (Chicago, IL) – General Manager February 2000 – April 2003 Worked with the Executive Producer in a 292-seat commercial theater. In three years, was promoted twice and served as General Manager from April 2002 until April 2003. Dramaturgy Experience ( * denotes new play/musical) La Jolla Playhouse (La Jolla, CA) Miss You Like Hell* by Quiara Alegría Hudes & Erin McKeown (dir.