Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 the Epic in Ancient Greece and in Ancient India

CHAPTER 2 THE EPIC IN ANCIENT GREECE AND IN ANCIENT INDIA Though the main focus of the present study is going to be characterization, it nnust be borne in mind that characterization in an epic narrative will not have the same complexion as characterization, say, in a novel or a play. It will be appropriate, therefore, to focus in this chapter on the nature of the epics under study. Greece and India are blessed by the epic muse for they are the only ones who produced full-length oral epics that reflect the throbbing heart and soul of the people of ancient times. Other countries like England, France, Germany, Norway and Finland have their epics of the medieval age such as Beowulf. Le Chanson de Roland. Nibelunaenlied. the Edda and the Saga, and Kalevala respectively. Epics belong to the 'heroic age' and their heroes fight bravely for fame and/or to save their people from some demon or other dangers. Physical strength and valour are of supreme importance to these epics as they deal with warfare. The epics of Greece and India possess all these characteristics but they are different from the medieval epics because they go far beyond this and reveal nobility of character portrayal and a tragic awareness of life. The Iliad, the Odvssev. the Vaimiki Ramavana. and the Mahabharata are in a class of their own owing to these rare qualities. Lascelles Abercrombie rightly says in his The Epic that the reading of The Faerie Queene or Divina Commedia is not in the least like the experience of reading of Paradise lost or the Iliad. -

THE SARANGA BIRDS About in the Forest with Another Female Bird Neglect Ing Wife and Children

, CHAPTER XVIII A saranga bird was living there with its four fledgelings. The male bird was pleasantly roaming THE SARANGA BIRDS about in the forest with another female bird neglect ing wife and children. The mother bird looked IN TilE STORIES narrate(l in the Puranas, birds and after its young ones. As the forest was set on nre beasts speak like men, and sometimes they give as commullCled hy Krishna alia Arjuna and the nre sound advice and even teach spiritual wisdom. But spread in all directions, doing its destruelive work, the natural qualities of those creatures are adroitly the worried mother bird began to lament: 'The nre made to peep through this human veil. is coming lIearer and nearer buming everything, and soon it will be here and destroy us. All· forest One of the characteristic beauties of the Puranic creatures are in despair and the air is full of the literature is this happy fusion of nature and imagi agonising crash of falling trees. Poor wingless nation. In a delightful passage in the Ramayana, babies! You will become a prey to the nre. What Hanuman, who is described as very wise and learned, shall I do? Your father has deserted us, and I am is made to frolic with apish joy, when he imagined not strong enough to flyaway carrying yOll with me." that the beautiful damsel he saw at Ravana's inner courtyard was Sita. To the mother who was wailing thus, the child ren said: "Mother, do not torment yourself on our It is IIsual to entertain children with stories in account; leave us to our fate. -

Auspicious Offering of Lord Shiva As A

Scholars International Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Tradit Complement Med ISSN 2616-8634 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3891 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijtcm Review Article Auspicious Offering of Lord Shiva as a Source of Natural Antiviral Compounds against COVID 19: A Review Yadav Yadevendra1*, Sharma Arun2, Sharma Usha3, Sharma Khemchand4 1Assistant Professor, P.G. Department of Rasa Shastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, Uttarakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, India 2PG Scholar, P.G. Department of Rasa Shastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, Uttarakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, India 3Associate Professor, P.G. Department of Rasa Shastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, Uttarakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, India 4Professor and Head, P.G. Department of Rasa Shastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, Uttarakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, India DOI: 10.36348/sijtcm.2020.v03i07.001 | Received: 26.06.2020 | Accepted: 03.07.2020 | Published: 08.07.2020 *Corresponding author: Dr. Yadevendra Yadav Abstract Offerings of flowers, leaves, fruits, cereals, foods and drinks to the Gods have been spoken about to a great extent in ancient Hindu scriptures such as Puranas and Vedas. These substances also have replete with significant medicinal values. ' Mahamrityunjaya Mantra Japa' means Great Death-conquering Mantra, is a verse (sukta) of the Rigveda. This mantra is addressed to Shiva for warding off death and bestows longevity. Lord Shiva idolizes with some astonishing substances like Bilva Patra, Bhang Patra, Arka Puspa and Ganga Jal in Mahamrityunjaya Mantra Japa'. Medicinal properties like, antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal, Anti-inflammatory, Analgesic, Anticancer, Antioxidant property of these have been reported by recent researches. -

Village Agriculture Assistant (Grade-II), Selection List - SRIKAKULAM DISTRICT

Village Agriculture Assistant (Grade-II), Selection List - SRIKAKULAM DISTRICT OUTSO OUTSO Venue to LOCA IS_MER DISTRI APGS_W IS_OUT OUTSOU URCE_ URCE_ Time of L_DIS WEIGHT COMM QUAL_Y SSC_YE ITORIO IS_EX_S attend for Date of CT_OP DISTRICT_OPT LOCAL_DIST CANDIDAT POST_ RITTEN TOTAL_ APGS_R GENDE PH_TYP SOURC RCE_DE EMP_S EMP_S SELECTION Sl. No TRICT HALLTICKET_NO CANDIDATE_NAME FATHERS_NAME AGE_M UNITY EAR_OF AR_OF_ IS_PH US_SPO ERVICE verificati TED_C ED_NAME RICT_NAME E_ID NAME _MARK MARKS ESULT R E E_EMPL PARTM ERVIC ERVIC certificates verfication _COD ARKS _ID _PASS PASS RTS_ME MEN UNDER ODE S OYEE ENT E_YEA E_MON on E N verficiation RS THS Gayatri Degree College, SRIKAKULA BONTHALA 101 101 SRIKAKULAM 190306000923 BONTHALA ARUNA 20245050 106 0 106 FEMALE BC-B 2019 2012NO--- No No No 0 0 1 25-09-19 10am M OC_OPEN_GEN Munasabpeta, ESWARARAO VAA VAA Srikakulam (GRADE-II) (GRADE-II) Gayatri Degree VIJAYA College, SRIKAKULA LOLUGU Agricul 101 101 SRIKAKULAM 190106000293 BHASKARARA 20214128 105.5 0 105.5 MALE BC-D 2006 1998NO --- No No Yes 2 3 2 25-09-19 10am M OC_OPEN_GEN Munasabpeta, SURYANARAYANA VAA VAA ture O Srikakulam (GRADE-II) (GRADE-II) (GRADE-II) (GRADE-II) Gayatri Degree College, SRIKAKULA BALA 101 113 KURNOOL 191306003124 BALA PULENDRA 20059377 104 0 104 MALE BC-D 2017 2010NO--- No No No 0 0 3 25-09-19 10am M OC_OPEN_GEN Munasabpeta, HANUMANTHU VAA VAA Srikakulam (GRADE-II) (GRADE-II) Gayatri Degree College, SRIKAKULA VIZIANAGARA B SANYASI 101 102 190306000939 BODDU GAYATHRI 20262999 104 0 104 FEMALE BC-D 2017 2011NO--- No -

![Shukra – Neeti the Teachings of Guru Sukracharya [ Brief from the Mahabharata ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2412/shukra-neeti-the-teachings-of-guru-sukracharya-brief-from-the-mahabharata-1342412.webp)

Shukra – Neeti the Teachings of Guru Sukracharya [ Brief from the Mahabharata ]

[email protected] SHUKRA – NEETI THE TEACHINGS OF GURU SUKRACHARYA [ BRIEF FROM THE MAHABHARATA ] Introduction : Guru Shukracharya He was born as the son of Rishi Brighu and his wife Ushana. The feminic natured Shukra is a Brahminical planet. He was born on Friday in the year Paarthiva on Sraavana Suddha Ashtami when Swathi Nakshatra is on the ascent. Hence, Friday is known as Shukravaar in Indian languages especially Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi , Gujarati and Kannada. He went on to study Vedas under rishi Angirasa but he was disturbed by Angirasa's favouritism to his son Brihaspati. He then went to study under rishi Gautama. He later performed penance to Lord Shiva and obtained the Sanjivani mantra (a hymn that can revive the dead). During this period Brihaspati became the Guru (Preceptor) of the divine people Devaa. Out of jealousy, Shukracharya decides to become the Guru of Asuras. He helps them achieve victory over the Devas and uses his magic to revive the dead and wounded Asuras. [email protected] In one story, Lord Vishnu is born as the Brahmin sage Vamana. Vamana comes to take the three worlds as alms from the asura King Bali. Lord Vishnu wanted to deceive the King Bali who was the grandson of the great ing Prahlad, in order to help the Devas. The sage Shukracharya identifies him immediately and warns the King. The King is however a man of his word and offers the gift to Vamana. Shukracharya, annoyed with the pride of the King, shrinks himself with his powers and sits in the spout of the vase, from which water has to be poured to seal the promise to the deity in disguise. -

Hymns to the Mystic Fire

16 Hymns to the Mystic Fire VOLUME 16 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 2013 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Hymns To The Mystic Fire Publisher’s Note The present volume comprises Sri Aurobindo’s translations of and commentaries on hymns to Agni in the Rig Veda. It is divided into three parts: Hymns to the Mystic Fire: The entire contents of a book of this name that was published by Sri Aurobindo in 1946, consisting of selected hymns to Agni with a Fore- word and extracts from the essay “The Doctrine of the Mystics”. Other Hymns to Agni: Translations of hymns to Agni that Sri Aurobindo did not include in the edition of Hymns to the Mystic Fire published during his lifetime. An appendix to this part contains his complete transla- tions of the first hymn of the Rig Veda, showing how his approach to translating the Veda changed over the years. Commentaries and Annotated Translations: Pieces from Sri Aurobindo’s manuscripts in which he commented on hymns to Agni or provided annotated translations of them. Some translations of hymns addressed to Agni are included in The Secret of the Veda, volume 15 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. That volume consists of all Sri Aurobindo’s essays on and translations of Vedic hymns that appeared first in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1920. His writings on the Veda that do not deal primarily with Agni and that were not published in the Arya are collected in Vedic and Philological Studies, volume 14 of THE COMPLETE WORKS. -

Rigveda–A Study on Forty Hymns

Rig Veda A study of the forty hymns yasmaa%xarmatItao|hmaxaradip caao<ama: | Atao|isma laaokovaodo ca p`iqat: puruYaao<ama: || Since I am beyond mutable Knowledge and even the Immutable Wisdom, Therefore, I am the known as the Supreme One. - declares Sri Krishna Truth is a pathless land To communicate with one another, even if we know each other well, is extremely difficult. I may use words that may have to you significance different from mine. Understanding comes when we, you and I, meet on the same level at the same time. That happens only when there is real affection between people . That is real communion. Instantaneous understanding comes when we meet on the same level as the same time. - J. Krishnamurti First Edition 2006 Published by Nagesh D. Sonde 318, Raheja Crest, - 3, Link Road, Andheri West, Mumbai 400 053 Tele Nos . 2635 2743 - 44 Printed at New Age Printing Press Sayani Road, Mumbai – 400 025 Rupees Five Hundred Only. To My Sons Ashish and Devdatt With thanks for having fulfilled my expectations I had for them in leading their lives. * ‘Aqa ~yaao vaava laaoka:, manauYyalaaok: ip~ulaaokao dovalaaok: [it | saao|yaM manauYya laaok: pu~oNaOva jayya:, naanyaona kma-Naa: kma-Naa iptRlaaok: | dovalaaokao vaO laaokanaaM EaoYz:, tsmaaiWVaM p`SaMsaint ||’ Brihad Aranyaka Up. There are three worlds: The world of men, the world of ancestors and the world of divinities. The world of men is to be achieved through continuation of the line of offspring, not by performance of actions. The world of fathers is to be achieved through performance of actions in one’s life. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

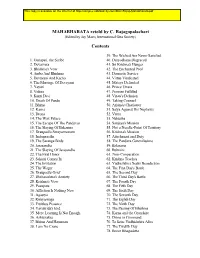

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Sri Vishnu Puraana, Amsha 4

SrI VishNu PurANam (Vol 4) Annotated Commentary in English by VidvAn SrI A. Narasimhan SvAmi Sincere thanks to "SrI Nrsimha Seva Rasikar" Oppiliappan Koil SrI V.Sadagopan SvAmi for hosting this title in his website www.sadagopan.org Sri Vishnu Puraana Classes conducted online by Sri A Narasimhan Notes prepared by Dr Amarnath Organized by Sri Tirunarayana Trust in memory of Mahavidvaan U Ve Sri V T Tirunarayana Iyengar Swamy **************************************************** Sri Tirunarayana Trust, ShanbagaDhama-Yaduvanam Villa 16, Brigade PalmGrove,Bogadi Road Mysuru 570026. India. Tel:91-97311 09114 Trust Website: www.tirunarayana.in Sri Vishnu Purana Class Notes: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!categories/sri- tirunarayana-trust-studygroup/ sri-vishnu-purana-class-notes Sri Vishnu Purana Study Website: https://sites.google.com/site/srivishnupuranastudy/ Study Video Playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist? list=PLqqIUwcsJupptBzp8KeXoDJIgHfS4MTo **************************************************** Classes Started on : 15 August 2018 Sri Vishnu Puraana, Amsha 4 || Atha Chaturtho Amshah || Now, the Amsha 4. || Atha Prathamo Adhyaayah || Brahma’s Vamsha Now Chapter 1 of Amsha 4. Sri Vishnu Puraana, Amsha 4, Chapter 1, Shloka 1: Maitreyah - Bhagavan yat naraih kaaryam saadhu karmani avasthitaih | Tat mahyam gurunaa aakhyaatam nitya naimittikaatmakam || Maitreyar – Those who are established in saadhu karma, vaidika karmaas, whatever one has to do, that you told me in great detail. Nitya and Naimittika karmaas which are very much required, -

THE VISHNU PURANA the Vishnu Purana Has Twenty-Three Thousand

THE VISHNU PURANA The Vishnu Purana has twenty-three thousand shlokas. Skanda Purana has eighty-one thousand shloka and Markandeya Purana only nine thousand. The Vishnu Purana also has six major sections or amshas, although the last of these is really short. Maitreya and Parashara Once the sage Maitreya came to the sage Parashara and wanted to know about the creation of the universe. And this is what Parashara told him. In the beginning the universe was full of water. But in that water there emerged a huge egg (anda) that was round like a water-bubble. The egg became bigger and bigger and inside the egg there was Vishnu. This egg was called Brahmanda. And inside Brahmanda there were the mountains and the land, the oceans and the seas, the gods, demons and humans and the stars. On all sides, the egg was surrounded by water, fire, wind, the sky and the elements. Inside the egg, Vishnu adopted the form of Brahma and proceeded to create the universe. When the universe is to be destroyed, it is Vishnu again who adopts the form of Shiva and performs the act of destruction. Let us therefore salute the great god Vishnu. There are four yugas or eras. These are called krita (or satya), treta, dvapara and kali. Krita era consists of four thousand years, treta of three thousand, dvapara of two thousand and kali of one thousand. All the four eras thus pass in ten thousand. And when all the four eras have passed one thousand times each, that is merely one day for Brahma. -

SWASTIKA the Pattern and Ideogram of Ideogram and Pattern The

Principal Investigators Exploring Prof. V. N. Giri the pattern and ideogram of Prof. Suhita Chopra Chatterjee Prof. Pallab Dasgupta Prof. Narayan C. Nayak Prof. Priyadarshi Patnaik pattern and ideogram of Prof. Aurobindo Routray SWASTIKA Prof. Arindam Basu Prof. William K. Mohanty Prof. Probal Sengupta Exploring the A universal principle Prof. Abhijit Mukherjee & of sustainability Prof. Joy Sen SWASTIKA of sustainability A universal principle SandHI INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR The Science & Heritage Initiative www.iitkgpsandhi.org INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR Exploring the pattern and ideogram of SWASTIKA A universal principle of sustainability SandHI The Science & Heritage Initiative INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR ii iii Advisor Prof. Partha P. Chakrabarti Director, IIT Kharagpur Monitoring Cell Prof. Sunando DasGupta Dean, Sponsored Research and Industrial Consultancy, IIT Kharagpur Prof. Pallab Dasgupta Associate Dean, Sponsored Research and Industrial Consultancy, IIT Kharagpur Principal Investigator (overall) Prof. Joy Sen Department of Architecture & Regional Planning, IIT Kharagpur Vide order no. F. NO. 4-26/2013-TS-1, Dt. 19-11-2013 (36 months w.e.f 15-1-2014 and 1 additional year for outreach programs) Professor-in-Charge, Documentation and Dissemination Prof. Priyadarshi Patnaik Department of Humanities & Social Sciences, IIT Kharagpur Research Scholars Group (Coordinators) Sunny Bansal, Vidhu Pandey, Tanima Bhattacharya, Shreyas P. Bharule, Shivangi S. Parmar, Mouli Majumdar, Arpan Paul, Deepanjan Saha, Suparna Dasgupta, Prerna Mandal Key Graphics Support Tanima Bhattacharya, Research Scholar, IIT Kharagpur Exploring ISBN: 978-93-80813-42-4 the pattern and ideogram of © SandHI A Science and Heritage Initiative, IIT Kharagpur Sponsored by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, Government of India Published in July 2016 SWASTIKA www.iitkgpsandhi.org A universal principle Design & Printed by Cygnus Advertising (India) Pvt. -

Vedic and Upanishadic Aesthetics

Dr. Shakuntala Gawde Department of Sanskrit University of Mumbai www.shakuntalagawde.com [email protected] Vedic Literature Vedas / Shrutis- revealed knowledge Four Vedas- different divisions Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda Samhita Brahmana Aranyaka Upanishad Rigveda Different hymns to deities Divided into ten Mandalas Collection of Suktas Indra, Ushas, Agni, Maruts, Ashvina, Parjanya Different schools of interpretation Indra Warrior and conqueror Macdonell- National god of Vedic Indians Thunder god / Sun god (destroyer of demons of drought and darkness) / warrior god Vrtrahan- Killed Vrtrasura, releases cows and waters Killed Shambara, Vala who live on mountain Anthropomorphism- With body, hands and arms (RV II.16.2) Suhipra (fair-liped) Tawny haired and tawny bearded (RV X.23.4) His arms as wielding the thunderbolt, golden armed, iron-like Whole appearance as tawny, ruddy, golden (RV VII.34.4) Agni 200 hymns Sacrificial fire is personified Butter backed, flame-haired, tawny haired, tawny beard Sharp or burning jaws, golden teeth Compared to many animals Calf when born and roaring bull when grows (RV X.8.1) Looks like god-carrying horse (RV III.27.14) Divine bird (RV I.164.52) Son of ten mothers (RV I.95.2) Ushas Beautiful young damsel Like a dancer she comes (RV I.92.4) Like a maiden decked by her mother she shows her beautified form (RV I.123.11) Clothed with light, she appears in the east (RV.I.124.3) वलश्ललाया, चित्रभघा, भघोनी, नेत्री, हशयण्मलर्ाा देलाना車 िषु: वुबगा लशन्ती