The Baltic States' Integration Into the European Division of Labour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

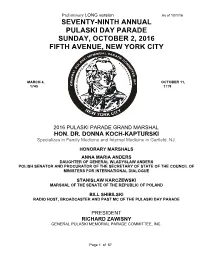

Seventy-Ninth Annual Pulaski Day Parade Sunday, October 2, 2016 Fifth Avenue, New York City

Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY MARCH 4, OCTOBER 11, 1745 1779 2016 PULASKI PARADE GRAND MARSHAL HON. DR. DONNA KOCH-KAPTURSKI Specializes in Family Medicine and Internal Medicine in Garfield, NJ. HONORARY MARSHALS ANNA MARIA ANDERS DAUGHTER OF GENERAL WLADYSLAW ANDERS POLISH SENATOR AND PROCURATOR OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS FOR INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE STANISLAW KARCZEWSKI MARSHAL OF THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND BILL SHIBILSKI RADIO HOST, BROADCASTER AND PAST MC OF THE PULASKI DAY PARADE PRESIDENT RICHARD ZAWISNY GENERAL PULASKI MEMORIAL PARADE COMMITTEE, INC. Page 1 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 ASSEMBLY STREETS 39A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. M A 38 FLOATS 21-30 38C FLOATS 11-20 38B 38A FLOATS 1 - 10 D I S O N 37 37C 37B 37A A V E 36 36C 36B 36A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. Page 2 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE 79TH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE COMMEMORATING THE SACRIFICE OF OUR HERO, GENERAL CASIMIR PULASKI, FATHER OF THE AMERICAN CAVALRY, IN THE WAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE BEGINS ON FIFTH AVENUE AT 12:30 PM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016. THIS YEAR WE ARE CELEBRATING “POLISH- AMERICAN YOUTH, IN HONOR OF WORLD YOUTH DAY, KRAKOW, POLAND” IN 2016. THE ‘GREATEST MANIFESTATION OF POLISH PRIDE IN AMERICA’ THE PULASKI PARADE, WILL BE LED BY THE HONORABLE DR. DONNA KOCH- KAPTURSKI, A PROMINENT PHYSICIAN FROM THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Minority Rights After EU Enlargement: a Comparison of Antigay Politics in Poland and Latvia

Original Article Minority rights after EU enlargement: A comparison of antigay politics in Poland and Latvia Conor O’Dwyer* and Katrina Z.S. Schwartz Department of Political Science, University of Florida, 234 Anderson Hall, PO Box 117325, Gainesville, Florida 32611-7325, USA. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author. Abstract This paper examines the recent backlash against gay rights in Poland and Latvia as a test case of the depth and breadth of ‘europeanization’ in the new postcommunist member-states of the European Union (EU). We argue that antigay mobilization in these countries constitutes illiberal governance (and thus a failure of europeanization) on three grounds: failure of institutional protections for sexual minorities, broad inclusion of illiberal elites in mainstream politics and virulence of antigay rhetoric by political elites in the public sphere. To explain the stalled europeanization of nondiscrimination norms regarding sexual minorities, we apply two analytical models widely used to explain successful norm adoption in other policy areas: the ‘external incentives’ and ‘social learning’ models. We find that in the case of gay rights, EU conditionality was weak, and national identity and ‘resonance’ operated against norm adoption, as did domestic institutions (namely, weakly institutionalized party systems). The EU might have overcome these obstacles through persuasion, but deliberative processes were lacking. Our analysis suggests that some of the key factors underlying both models of norm adoption operate differently in the new, postaccession context, and that social learning is likely to play a greater role in postaccession europeanization. Comparative European Politics (2010) 8, 220–243. doi:10.1057/cep.2008.31 Keywords: Latvia; Poland; sexual minorities; European Union; europeanization; illiberalism Introduction In May 2004, Poland and Latvia joined the European Union (EU), ending a long process in which the strength of their democratic institutions was carefully tested and validated by the European Commission. -

Forced Displacement – Global Trends in 2015

GLObaL LEADER ON StatISTICS ON REfugEES Trends at a Glance 2015 IN REVIEW Global forced displacement has increased in 2015, with record-high numbers. By the end of the year, 65.3 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. This is 5.8 million more than the previous year (59.5 million). MILLION FORCIBLY DISPLACED If these 65.3 million persons 65.3 WORLDWIDE were a nation, they would make up the 21st largest in the world. 21.3 million persons were refugees 16.1 million under UNHCR’s mandate 5.2 million Palestinian refugees registered by UNRWA 40.8 million internally displaced persons1 3.2 million asylum-seekers 12.4 24 86 MILLION PER CENT An estimated 12.4 million people were newly displaced Developing regions hosted 86 per due to conflict or persecution in cent of the world’s refugees under 2015. This included 8.6 million UNHCR’s mandate. At 13.9 million individuals displaced2 within people, this was the highest the borders of their own country figure in more than two decades. and 1.8 million newly displaced The Least Developed Countries refugees.3 The others were new provided asylum to 4.2 million applicants for asylum. refugees or about 26 per cent of the global total. 3.7 PERSONS MILLION EVERY MINUTE 183/1000 UNHCR estimates that REFUGEES / at least 10 million people On average 24 people INHABITANTS globally were stateless at the worldwide were displaced from end of 2015. However, data their homes every minute of Lebanon hosted the largest recorded by governments and every day during 2015 – some number of refugees in relation communicated to UNHCR were 34,000 people per day. -

The European Union V. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests As a Party to the International Criminal Court, 27 Hastings Int'l & Comp

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 27 Article 5 Number 1 Fall 2003 1-1-2003 The urE opean Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court Barbi Appelquist Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Barbi Appelquist, The European Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court, 27 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 77 (2003). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol27/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The European Union v. the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Estonia's Conflicting Interests as a Party to the International Criminal Court By BARBI APPELQUIST* Introduction Estonia, the United States and all current members of the European Union have signed the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.' This body of public international law protects the following human rights of alleged criminals: "the protection against arbitrary arrest, detention, or invasions of privacy; a presumption of innocence; and a promise of 'full equality' at a fair, public trial, before a neutral arbiter, with 'all the guarantees necessary' for the defense."2 The International Criminal Court (ICC) was created to provide a fair trial for those accused of certain particularly serious crimes in an objective international setting.3 Estonia became a party to the ICC when its President signed the * J.D. -

Capital, Labor, and the Prospects of the European Social Model in The

Central and Eastern Europe Working Paper 58 Capital, Labor, and the Prospects of the European Social Model in the East by Dorothee Bohle Béla Greskovits Central European University Central European University Political Science Department; Department of International Minda de Gunzburg Relations and European Studies; Center for European Studies Committee on Degrees in Social Harvard University Studies, Harvard University ABSTRACT During the past decade of European economic integration vastly worse standards have emerged in work conditions, industrial relations, and social welfare in Eastern Europe than in the West. Area scholars ex- plain this divide by labor weakness caused by the ideological legacy of communism, and do not problema- tize the impact of transnational capital. In contrast, this essay argues that the reason why the European so- cial model has not traveled to the East is that its socio-economic foundations, the industrial building blocks of the historical compromise between capital and labor, have not traveled either. In the West, the compro- mise had been rooted in capital-intensive consumer durables industries, such as car-manufacturing, and their suppliers. These sectors brought together organized and vocal labor with businesses willing to accom- modate workers’ demands, because for them labor had been less a problem as a cost-factor and more im- portant as factor of demand. However, the main driving force of the eastward expansion of European capi- tal has been the relocation of labor-intensive activities where business relies on sweating masses of work- ers, whose importance as consumers is marginal, and who are weak in the workplace and the marketplace. -

Le Gala De La Croix-Rouge Monégasque, Histoire D'un

Le Gala de la Croix-Rouge monégasque, Histoire d’un événement lié à la renommée internationale de Monaco Fondée le 3 mars 1948 par le Prince Louis II 1948 - Président : Le Prince Rainier III 10 août 1948 Nuit de la Croix-Rouge, Maurice Chevalier Sporting d’Eté 17 janvier 1949 Nuit de la Croix-Rouge Sporting d’Hiver Présentateurs : Robert Beauvais et Gisel Parry 15 août 1950 Nuit de la Croix-Rouge Sporting d’Eté 5 août 1951 Bal des Petits Lits Blancs Sporting d’Eté 6 septembre 1952 Défilé de mode Christian Dior Sporting d’Eté 4 août 1953 Zizi Jeanmaire, Alexandre Kalioujny Sporting d’Eté 23 juillet 1954 Billy Eckstine Sporting d’Eté 29 juillet 1955 Danny Kaye Sporting d’Eté 27 juillet 1956 Georgia Gibbs, Charly McCarthy & Edgar Bergen Sporting d’Eté 19 juillet 1957 Eddie Fisher Sporting d’Eté Présentateurs : Henry Astric (Directeur Artistique de la Société des Bains de Mer) et Vicky Autier Mai 1958 - Présidente : La Princesse Grace 18 juillet 1958 10ème Anniversaire Sarah Vaughan Sporting d’Eté Présentateurs : Henry Astric et Vicky Autier 7 août 1959 Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Martin Sporting d’Eté Présentateur : Peter Ustinov Orchestre Jonan Jones 7 août 1960 Béatrice Lillie, Nat King Cole Sporting d’Eté Présentateurs : Henry Astric et Francis Blanche 11 août 1961 Sammy Davis Jr Sporting d’Eté Présentateur : Robert Lamoureux 27 juillet 1962 Rosemary Clooney Sporting d’Eté Présentateur : Charles Trénet 9 août 1963 Sacha Distel Sporting d’Eté Présentateur : Vittorio Gassman 7 août 1964 Eleanor Powell Sporting d’Eté Présentateurs : Jacques Charon -

Why Doesn't the United States Have a European-Style Welfare State?

0332-04-Alesina 1/3/02 15:31 Page 187 ALBERTO ALESINA Harvard University EDWARD GLAESER Harvard University BRUCE SACERDOTE Dartmouth College Why Doesn’t the United States Have a European-Style Welfare State? EUROPEAN GOVERNMENTS REDISTRIBUTE income among their citizens on a much larger scale than does the U.S. government. European social pro- grams are more generous and reach a larger share of citizens. European tax systems are more progressive. European regulations designed to protect the poor are more intrusive. In this paper we try to understand why. The literature on the size of government is rich and varied. However, here we do not focus on the size of government as such, but rather on the redistributive side of government policies. Thus our goal is in one sense narrower than answering the question, “What explains the size of govern- ment?” since we focus on a single, but increasingly important, role of fis- cal policy. Yet in another sense our focus is broader, because redistributive policies go beyond the government budget—think, for instance, of labor market policies. We consider economic, political, and behavioral explanations for these differences between the United States and Europe. Economic explanations focus on the variance of income and the skewness of the income distribu- tion before taxes and transfers, the social costs of taxation, the volatility of income, and expected changes in income for the median voter. We con- clude that most of these theories cannot explain the observed differences. We are grateful to our discussants for very useful suggestions. We also thank William Easterly, Benjamin Friedman, Michael Mandler, Casey Mulligan, Roberto Perotti, Andrei Shleifer, Theda Skocpol, and a large number of conference participants for very useful com- ments. -

SMUGGLING of MIGRANTS from WEST AFRICA to EUROPE What Is the Nature of the Market?

4.2. From Africa to Europe: Flow map BM 01.03.09 SPAIN ITALY TURKEY Mediterranean Atlantic Sea Ocean Lampedusa GREECE (ITALY) MALTA CANARY TUNISIA ISLANDS MOROCCO (SPAIN) ALGERIA Western Sahara LIBYA EGYPT MAURITANIA Red Sea MALI SENEGAL SUDAN CHAD THE GAMBIA NIGER GUINEA-BISSAU GUINEA BURKINA FASO BENIN SIERRA Flows of irregular migrants TOGO LEONE CÔTE discussed in this chapter D’IVOIRE LIBERIA GHANA NIGERIA 1,000 km SMUGGLING OF MIGRANTS FROM Figure 19: Region of origin of irregular WEST AFRICA TO EUROPE migrants detected in Europe Evolution of measured apprehensions at several European countries' borders, 1999-2008 (vertical scales are differents) Migrant smuggling occurs most frequently along the fault 300,000 lines between twoMigrants regions appr ehendedof vastly in Spain different levels of Migrantsdevel- apprehended250,000 in Italy 26,140 Migrants apprehended in Malta at sea border (thousands) (thousands) 23,390and Africans apprehended in Greece opment, such as West Europe and West Africa. Though the (thousands) 20,465 30 Sahara Desert and theStrait Mediterranean of Gibraltar/ Sea pose formidable50 200,000 3 Alborean Sea Canary Islands 20 Malta 17,665 obstacles, thousands of people cross them each year in40 order 2.5 Rest of Italy150,000 10 2 to migrate irregularly. Almost all of those who choose30 to do Sicily* Egyptians 244,495 230,555 in Greece so require assistance, and the act of rendering this assistance 100,000 1.5 212,680 20 Somali 171,235 for gain constitutes the crime of migrant smuggling.40 1 in Greece 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 10 Sardinia 50,000 0.5 In recent years, about 9% of irregular migrants detected in 0 Europe came from West Africa. -

Europe, Russia, and Minority Inclusion in Estonia and Latvia

Introduction The Strategic Framing of Baltic Security Europe, Russia, and Minority Inclusion After the collapse of communism, most Central and Eastern European (CEE) elites were eager to resurrect national identities based on the ethnic majority culture and to “return to Europe” by pursuing membership in European in- stitutions. These goals were not easily reconciled. Minority groups promoted conflicting conceptions of the nation and claims about their place within the (re)constructed post-communist space. Ignoring minority claims was diffi- cult. Not only did kin-states advocate on behalf of their ethnic kin living in other states, but the European Union made membership conditional on the protection of minorities. In Estonia and Latvia, nationalizing policies that privileged ethnic majorities and politically disenfranchised large numbers of Russian-speakers drew an unprecedented amount of attention from both European institutions and the Russian kin-state. The influence of European institutions and Russia on the minority situation in these states has been the subject of considerable scholarly debate. Estonia and Latvia joined the European Union (EU) and the North Atlan- tic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004. In the period leading up to acces- sion, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the Council of Europe (CE) monitored the minority situation and issued nu- merous recommendations for policy reforms. These recommendations were reinforced by EU conditionality, which made EU membership conditional on the removal of some of the most exclusionary aspects of citizenship and lan- guage policies. While these reforms are often considered “wins” for Europe- an institutions, early optimism that European institutions would transform the minority situation in these countries soon gave way to skepticism and disappointment. -

Miss France 2021 Publié Par Aurélie Binoist Le 01/12/2020

2 ELECTION 2021 Samedi 19 décembre à 21:05 En direct du Puy du Fou Une soirée présentée par Jean-Pierre Foucault Accompagné de Sylvie Tellier Proposée par l’Organisation Miss France Produite par EndemolShine France Réalisée par Franck Broqua L’Organisation Miss France célèbre cette année le centenaire des concours de beauté en France. Chaque année, des jeunes femmes modernes, libres et déterminées se lancent dans une expérience unique. Une aventure exceptionnelle qui marquera à jamais leur vie. Au fil du temps, l’élection de Miss France est devenue une véritable institution et un rendez-vous in- contournable aux yeux des Français. Un siècle de couronnement, d’élégance, d’engagement et de partage avec les Français. Pour célébrer ce bel anniversaire, Jean-Pierre Foucault présentera l’élection de Miss France 2021, accompagné de Sylvie Tellier, le samedi 19 décembre, en direct du Puy du Fou. C’est dans cet écrin historique et féérique que les 29 Miss régionales prépareront assidûment un show unique. Pour la première fois dans l’histoire de l’émission, une trentaine d’anciennes Miss France seront réunies sur le plateau pour offrir un instant de nostalgie aux téléspecta- teurs. Elles joueront le rôle de marraine en accompagnant la promotion 2021. À année exceptionnelle, jury d’exception. Il sera composé exclusivement de Miss France issues de toutes les générations. Ensemble, elles auront l’honneur d’élire leur ambassadrice, conjointement avec les Français. À quelques jours de l’élection, les 29 Miss régionales se présenteront devant un jury de présélection qui définira les 15 demi-finalistes. Ces dernières seront ensuite soumises au vote 50/50 des téléspectateurs et du jury présent sur le plateau. -

Baltic States

ULDIS OZOLINS THE IMPACT OF EUROPEAN ACCESSION UPON LANGUAGE POLICY IN THE BALTIC STATES (Received 31 January 2003; accepted in revised form 11 July 2003) ABSTRACT. The deliberate changes to language regime undertaken in post-Soviet Estonia and Latvia have had significant repercussions for their accession to the EU and NATO. Charges of discrimination against Russian-speaking minorities have led countless European delegations to survey the Baltic States, resulting in a mixture of approval, advice and warnings on language, citizenship and integration issues. While these interventions have been justified by assertions of international human rights standards, such standards as exist have been devised for very different minority situations, and their relevance to the Baltic States is often contested. The article points to an evolving critique of the minority- rights based approach of European institutions, and examines the specific sociolinguistic situation in the Baltic including the often unrecognised attitudes of the Russian-speaking minorities. The Baltic case has wider resonance for other small national languages seeking to reassert their status against former imperialistic language regimes. KEY WORDS: Baltic States, changes to language regimes, citizenship, European organ- isations, human rights standards, language laws, language minorities, minority rights, post-colonialism INTRODUCTION In November and December 2002, at formal meetings in Prague and Copenhagen respectively, invitations to join NATO and the EU were extended inter alia to the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Besides the expected issues of defence budgets and fish quotas, issues of language policy have featured more prominently in these organ- isations’ vetting of candidate countries than may have been expected, extending to threats of non-acceptance if European or NATO demands are not met.