Estonia Promoting Social Inclusion of Roma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seventy-Ninth Annual Pulaski Day Parade Sunday, October 2, 2016 Fifth Avenue, New York City

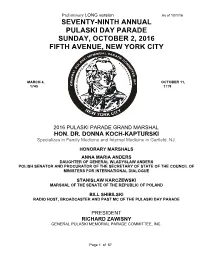

Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY MARCH 4, OCTOBER 11, 1745 1779 2016 PULASKI PARADE GRAND MARSHAL HON. DR. DONNA KOCH-KAPTURSKI Specializes in Family Medicine and Internal Medicine in Garfield, NJ. HONORARY MARSHALS ANNA MARIA ANDERS DAUGHTER OF GENERAL WLADYSLAW ANDERS POLISH SENATOR AND PROCURATOR OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS FOR INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE STANISLAW KARCZEWSKI MARSHAL OF THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND BILL SHIBILSKI RADIO HOST, BROADCASTER AND PAST MC OF THE PULASKI DAY PARADE PRESIDENT RICHARD ZAWISNY GENERAL PULASKI MEMORIAL PARADE COMMITTEE, INC. Page 1 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 ASSEMBLY STREETS 39A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. M A 38 FLOATS 21-30 38C FLOATS 11-20 38B 38A FLOATS 1 - 10 D I S O N 37 37C 37B 37A A V E 36 36C 36B 36A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. Page 2 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE 79TH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE COMMEMORATING THE SACRIFICE OF OUR HERO, GENERAL CASIMIR PULASKI, FATHER OF THE AMERICAN CAVALRY, IN THE WAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE BEGINS ON FIFTH AVENUE AT 12:30 PM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016. THIS YEAR WE ARE CELEBRATING “POLISH- AMERICAN YOUTH, IN HONOR OF WORLD YOUTH DAY, KRAKOW, POLAND” IN 2016. THE ‘GREATEST MANIFESTATION OF POLISH PRIDE IN AMERICA’ THE PULASKI PARADE, WILL BE LED BY THE HONORABLE DR. DONNA KOCH- KAPTURSKI, A PROMINENT PHYSICIAN FROM THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. -

Here in 2017 Sillamäe Vabatsoon 46% of Manufacturing Companies with 20 Or More Employees Were Located

Baltic Loop People and freight moving – examples from Estonia Final Conference of Baltic Loop Project / ZOOM, Date [16th of June 2021] Kaarel Kose Union of Harju County Municipalities Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Baltic Loop connections Baltic Loop Final Conference / 16.06.2021 Strategic goals HARJU COUNTY DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2035+ • STRATEGIC GOAL No 3: Fast, convenient and environmentally friendly connections with the world and the rest of Estonia as well as within the county. • Tallinn Bypass Railway, to remove dangerous goods and cargo flows passing through the centre of Tallinn from the Kopli cargo station; • Reconstruction of Tallinn-Paldiski (main road no. 8) and Tallinn ring road (main highway no. 11) to increase traffic safety and capacity • Indicator: domestic and international passenger connections (travel time, number of connections) Tallinn–Narva ca 1 h NATIONAL TRANSPORT AND MOBILITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2021-2035 • The main focus of the development plan is to reduce the environmental footprint of transport means and systems, ie a policy for the development of sustainable transport to help achieve the climate goals for 2030 and 2050. • a special plan for the Tallinn ring railway must be initiated in order to find out the feasibility of the project. • smart and safe roads in three main directions (Tallinn-Tartu, Tallinn-Narva, Tallinn-Pärnu) in order to reduce the time-space distances of cities and increase traffic safety (5G readiness etc). • increase speed on the railways to reduce time-space distances and improve safety; shift both passenger and freight traffic from road to rail and to increase its positive impact on the environment through more frequent use of rail (Tallinn-Narva connection 2035 1h45min) GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CLIMATE POLICY UNTIL 2050 / NEC DIRECTIVE / ETC. -

Country Background Report Estonia

OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools Country Background Report Estonia This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Estonia, as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). The participation of the Republic of Estonia in the project was organised with the support of the European Commission (EC) in the context of the partnership established between the OECD and the EC. The partnership partly covered participation costs of countries which are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ programme. The document was prepared in response to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries. The opinions expressed are not those of the OECD or its Member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm Ministry of Education and Research, 2015 Table of Content Table of Content ....................................................................................................................................................2 List of acronyms ....................................................................................................................................................7 Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................................9 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................10 -

This Is the Published Version of a Chapter

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a chapter published in Conflict and Cooperation in Divided Towns and Cities. Citation for the original published chapter: Lundén, T. (2009) Valga-Valka, Narva – Ivangorod Estonia’s divided border cities – cooperation and conflict within and beyond the EU. In: Jaroslaw Jańczak (ed.), Conflict and Cooperation in Divided Towns and Cities (pp. 133-149). Berlin: Logos Thematicon N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-21061 133 Valga-Valka, Narva-Ivangorod. Estonia’s Divided Border Cities – Co-operation and Conflict Within and beyond the EU Thomas Lundén Boundary Theory Aboundary is a line, usually in space, at which a certain state of affairs is terminated and replaced by another state of affairs. In nature, boundaries mark the separation of different physical states (molecular configurations), e.g. the boundary between water and air at the surface of the sea, between wood and bark in a tree stem, or bark and air in a forest. The boundaries within an organized society are of a different character. Organization means structuration and direction, i.e. individuals and power resources are directed towards a specific, defined goal. This, in turn, requires delimitations of tasks to be done, as well as of the area in which action is to take place. The organization is defined in a competition for hegemony and markets, and with the aid of technology. But this game of definition and authority is, within the limitations prescribed by nature, governed by human beings. -

Researcher Mobility in Estonia and Factors That Influence Mobility

Researcher Mobility in Estonia and Factors that Influence Mobility Researcher Mobility in Estonia and Factors that Influence Mobility Authors: Rein Murakas (Editor), Indrek Soidla, Kairi Kasearu, Irja Toots, Andu Rämmer, Anu Lepik, Signe Reinomägi, Eve Telpt, Hella Suvi Published by Archimedes Foundation Translated by Kristi Hakkaja Graphic design by Hele Hanson-Penu / Triip Printed by Triip This publication is co-financed by the European Commission. ©Archimedes Foundation, 2007 The materials may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes if duly referred to. For commercial purposes a written permission must be obtained. ISBN 978–9985–9672–7–0 Dear Reader, The current survey was conducted in 2006 for Archimedes Foundation and the Esto- nian Ministry of Education and Research as part of the project EST-MOBILITY-NET, funded from the 6th EU Framework Pro- gramme for Research and Technological Estonia Development. The survey gives an overview of researcher mobility in Estonia and the factors that influence mobility, and draws parallels with similar surveys conducted in other countries. For the first time the survey studies the motivation of foreign researchers for coming to Estonia and the main reasons of Estonian researchers to go abroad to do research and to return to Estonia. The purpose of the project EST-MOBILITY- NET was to set up in Estonia a network of mobility centres giving mobile researchers and their families up-to-date information and support in all aspects related to mo- bility. The Estonian network, consisting of Archimedes Foundation, the Estonian Acad- emy of Sciences, the University of Tartu, Tallinn Technical University, the Estonian University of Life Sciences, and Tallinn Uni- versity, is a part of the pan-European ERA- MORE Network. -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Estonian Ministry of Education and Research

Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Tartu 2008 Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Estonian Ministry of Education and Research LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ESTONIA Tartu 2008 Authors: Language Education Policy Profile for Estonia (Country Report) has been prepared by the Committee established by directive no. 1010 of the Minister of Education and Research of 23 October 2007 with the following members: Made Kirtsi – Head of the School Education Unit of the Centre for Educational Programmes, Archimedes Foundation, Co-ordinator of the Committee and the Council of Europe Birute Klaas – Professor and Vice Rector, University of Tartu Irene Käosaar – Head of the Minorities Education Department, Ministry of Education and Research Kristi Mere – Co-ordinator of the Department of Language, National Examinations and Qualifications Centre Järvi Lipasti – Secretary for Cultural Affairs, Finnish Institute in Estonia Hele Pärn – Adviser to the Language Inspectorate Maie Soll – Adviser to the Language Policy Department, Ministry of Education and Research Anastassia Zabrodskaja – Research Fellow of the Department of Estonian Philology at Tallinn University Tõnu Tender – Adviser to the Language Policy Department of the Ministry of Education and Research, Chairman of the Committee Ülle Türk – Lecturer, University of Tartu, Member of the Testing Team of the Estonian Defence Forces Jüri Valge – Adviser, Language Policy Department of the Ministry of Education and Research Silvi Vare – Senior Research Fellow, Institute of the Estonian Language Reviewers: Martin Ehala – Professor, Tallinn University Urmas Sutrop – Director, Institute of the Estonian Language, Professor, University of Tartu Translated into English by Kristel Weidebaum, Luisa Translating Bureau Table of contents PART I. -

Planning and NSB Corridor in Estonia

Planning and NSB Corridor in Estonia Tavo Kikas Adviser 18.01.2017 Planning in Estonia • Planning and Building Act 1995 Nordic model Hierarchical system National – regional – local • Planning Act 2002 Changes on regional level • Planning Act 2015 Estonian Planning System Planning of lines: then and now • Planning Act 2002 Amendment about linear structures 2007 County-wide spatial plans Comprehensive plans • Planning Act 2015 National designated spatial plan (5-year margin) Others National designated spatial plan Local government designated spatial plan National Spatial Plan Estonia 2030+ NSB Corridor in Estonia • „Rail Baltica“ 1st stage: Tallinn-Tartu- Valga railway • Via Baltica: Tallinn-Pärnu-Ikla highway • Rail Baltic: rail-highway over Pärnu „Rail Baltica“: 1st stage • Tallinn-Tartu-Valga Planning Renovation 120 km/h • To do: Some renovations Separated level crossings Passing opportunities 160 km/h Via Baltica • Tallinn-Pärnu-Ikla: Mostly 4 lanes Some trace corrections Room for separated level crossings • Adopted: In Pärnu County: 01.10.2012 In Harju County: 14.11.2014 In Rapla County: 23.05.2016 • To do: Designing Rail Baltic: facts • North-South railway connecting Nordic and Baltic region to Western Europe • Passenger and freight • Double-track at gauge 1,435 mm • Powered by electricity • Speed up to 240 km/h • Stops at Tallinn and Pärnu; possibility in Rapla • Less than 1 hour from Tallinn to Pärnu and less than 2 hours from Tallinn to Riga • Total length ca 700 km, ca 200 km in Estonia • Co-operation Estonia – Latvia – Lithuania; Finland and Poland involved • Route runs through Harju, Rapla and Pärnu Counties • Modern railway with low noise and vibration • No same-level-crossings means safer railway • Completion: 2022-2025. -

Rmk Annual Report 2019 Rmk Annual Report 2019

RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 RMK AASTARAAMAT 2019 | PEATÜKI NIMI State Forest Management Centre (RMK) Sagadi Village, Haljala Municipality, 45403 Lääne-Viru County, Estonia Tel +372 676 7500 www.rmk.ee Text: Katre Ratassepp Translation: TABLE OF CONTENTS Interlex Photos: 37 Protected areas Jarek Jõepera (p. 5) 4 10 facts about RMK Xenia Shabanova (on all other pages) 38 Nature protection works 5 Aigar Kallas: Big picture 41 Põlula Fish Farm Design and layout: Dada AD www.dada.ee 6–13 About the organisation 42–49 Visiting nature 8 All over Estonia and nature awareness Typography: Geogrotesque 9 Structure 44 Visiting nature News Gothic BT 10 Staff 46 Nature awareness 11 Contribution to the economy 46 Elistvere Animal Park Paper: cover Constellation Snow Lime 280 g 12 Reflection of society 47 Sagadi Forest Centre content Munken Lynx 120 g 13 Cooperation projects 48 Nature cameras 49 Christmas trees Printed by Ecoprint 14–31 Forest management 49 Heritage culture 16 Overview of forests 19 Forestry works 50–55 Research 24 Plant cultivation 52 Applied research 26 Timber marketing 56 Scholarships 29 Forest improvement 57 Conference 29 Forest fires 30 Waste collection 58–62 Financial summary 31 Hunting 60 Balance sheet 62 Income statement 32–41 Nature protection 63 Auditor’s report 34 Protected species 36 Key biotypes 64 Photo credit 6 BIG PICTURE important tasks performed by RMK 6600 1% people were employed are growing forests, preserving natural Aigar Kallas values, carrying out nature protection of RMK’s forest land in RMK’s forests during the year. -

Revitalisering Av Historiske Bykjerner Ni Utvalgte Estiske Byer

Revitalisering av historiske bykjerner Ni utvalgte estiske byer Estland har 12 beskyttede kulturmiljøer – Heritage Conservation Areas – hvorav 11 er i historiske bykjerner. Utlysningen «Historic old town centres with cultural heritage protection areas» retter seg mot de 9 beskyttede kulturmiljøene som ligger i henholdsvis byene Pärnu, Haapsalu, Kuressaare, Rakvere, Paide, Viljandi, Võru, Valga og Lihula. Mange av disse byene lider av synkende befolkningstall, som skyldes både lav fødselsrate og høy grad av fraflytting. Dette er en del av en ond sirkel av begrensede arbeidsmuligheter, lite investeringer i byene, og, i verste tilfelle, tap av byens identitet. På tross av disse utfordringene har de ni ovennevnte byene hver sine unike kulturmiljøer med bevarte historiske områder. PÄRNU Fylke: Pärnu fylke Grunnlagt: 1251 Areal: 32,22 km² Befolkning: 39 605 (2020) Befolkningstetthet: 1200 innb./km² Pärnu gamleby. Foto: ERR Pärnu er, med sine 39 605 (2020) innbyggere, Estlands fjerde største by. Den ligger sørvest i landet og har fått kallenavnet «Estlands sommerhovedstad» på grunn av sin rolle som feriedestinasjon. Økonomien er også sterkt knyttet til sesongaktiviteter og turisme. Dersom man ikke tar hensyn til sesong-baserte endringer, ligger befolkningstallet i Pärnu relativt stabilt, om enn med en svak nedgang. Den markante økningen i folketall sammenlignet med folketellingen i 2011 skyldes endringer i kommunegrensene. Villa Ammende. Foto: Visit Estonia. https://www.visitestonia.com/en/villa-ammende Det røde tårnet. Foto: PuhkaEestis.ee 2 https://www.puhkaeestis.ee/et/punane-torn Pärnu kulturmiljø De eldste områdene i kulturmiljøet i Pärnu er knyttet til byens middelalderslott og til den Hanseatiske byen. Spor etter Pärnu middelalderby er bevart, inkludert «det røde tårnet» og det historiske gatenettet, men det er det senere, barokke Pärnu som er mest tydelig. -

Ownership Reform and the Implementation of the Ownership Reform in the Republic of Estonia in 1991-2004

OWNERSHIP REFORM AND THE IMPLEMENTATION OF OWNERSHIP REFORM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA IN 1991-2004 R E P O R T Compiled by: Expert Committee of Legislative Proceeding of Crimes Against Democracy, from April 8 , 2004.a.D. Institute of Defending European Citizens in Estonia Expert Group of Legislative Proceeding of Crimes Against the State Arendia Elita von Wolsky FF [email protected] A p r i l 2004 T A L L I N N Ownership Reform and the Implementation of the Ownership Reform in the Republic of Estonia in 1991-2004. Report. The report has been prepared in co-operation with: United States President Administration, Union of Estonian Mothers, Expert Committee of the Estonian Centre Party Council of Tenants of Resituated Dwellings, Estonian Pensioners Union, Minority Nations Assembly of Estonia, Estonian Association of Tenants, European Commission Enlargement Directorate, European Commission Secretary-General, President of the European Commission, European Ombudsman, Republic of Estonia Ministry of Justice, Republic of Estonia Ministry of Defence, Republic of Estonia Defence Police Board, Republic of Estonia Ministry of Economy and Communications, Prime Minister of the Republic of Estonia, Republic of Estonia Police Board, Office of the President of the Republic of Estonia, President of the Republic of Estonia, Republic of Estonia State Archives, Riigikogu (parliament) of the Republic of Estonia, Supreme Court of the Republic of Estonia, State Audit Office of the Republic of Estonia, Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Estonia, Republic -

Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe

Cover_WHO_nr52.qxp_Mise en page 1 20/08/2019 16:31 Page 1 51 THE ROLE OF PUBLIC HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS IN ADDRESSING PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEMS IN EUROPE PUBLIC HEALTH IN ADDRESSING ORGANIZATIONS PUBLIC HEALTH THE ROLE OF Quality improvement initiatives take many forms, from the creation of standards for health Improving healthcare 53 professionals, health technologies and health facilities, to audit and feedback, and from fostering a patient safety culture to public reporting and paying for quality. For policy- makers who struggle to decide which initiatives to prioritise for investment, understanding quality in Europe Series the potential of different quality strategies in their unique settings is key. This volume, developed by the Observatory together with OECD, provides an overall conceptual Health Policy Health Policy framework for understanding and applying strategies aimed at improving quality of care. Characteristics, effectiveness and Crucially, it summarizes available evidence on different quality strategies and provides implementation of different strategies recommendations for their implementation. This book is intended to help policy-makers to understand concepts of quality and to support them to evaluate single strategies and combinations of strategies. Edited by Quality of care is a political priority and an important contributor to population health. This Reinhard Busse book acknowledges that "quality of care" is a broadly defined concept, and that it is often Niek Klazinga unclear how quality improvement strategies fit within a health system, and what their particular contribution can be. This volume elucidates the concepts behind multiple elements Dimitra Panteli of quality in healthcare policy (including definitions of quality, its dimensions, related activities, Wilm Quentin and targets), quality measurement and governance and situates it all in the wider context of health systems research.