Languages on Stage: Linguistic Pluralism and Community Formation in the Nineteenth-Century Parsi Theatre1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

Mahendra Singh Dhoni Exemplified the Small-Town Spirit and the Killer Instinct of Jharkhand by Ullekh NP

www.openthemagazine.com 50 31 AUGUST /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 34 31 AUGUST 2020 CONTENTS 31 AUGUST 2020 7 8 9 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI NOTEBOOK SOFT POWER WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY Who’s afraid of By Virendra Kapoor By Anil Dharker The Gandhi Purana By Jayanta Ghosal The tree of life Facebook? By Makarand R Paranjape By Srinivas Reddy By S Prasannarajan S E AG IM Y 22 THE LEGEND AND LEGACY OF TT E G MAHENDRA SINGH DHONI A cricket icon calls it a day By Lhendup G Bhutia 30 A WORKING CLASS HERO He smiled as he killed by Tunku Varadarajan 32 CAPTAIN INDIA It is the second most important job in the country and only the few able to withstand 22 its pressures leave a legacy By Madhavankutty Pillai 36 DHONI CHIC The cricket story began in Ranchi but the cultural phenomenon became pan-Indian By Kaveree Bamzai 40 THE PASSION OF THE BOY FROM RANCHI Mahendra Singh Dhoni exemplified the small-town spirit and the killer instinct of Jharkhand By Ullekh NP 44 44 The Man and the Mission The new J&K Lt Governor Manoj Sinha’s first task is to reach out and regain public confidence 48 By Amita Shah 48 Letter from Washington A Devi in the Oval? By James Astill 54 58 64 66 EKTA KAPOOR 2.0 IMPERIAL INHERITANCE STAGE TO PAGE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US Her once venerated domestic Has the empire been the default model On its 60th anniversary, Bangalore Little Streaming blockbusters goddesses and happy homes are no for global governance? Theatre produces a collection of all its By Rajeev Masand longer picture-perfect By Zareer Masani plays performed over the decades By Kaveree Bamzai By Parshathy J Nath Cover photograph Rohit Chawla 4 31 AUGUST 2020 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP Congratulations and thanks to Open for such a wide EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai range of brilliant writing in its Freedom Issue (August (Mumbai Bureau Chief), 24th, 2020). -

Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu)

Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF MODERN INDIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERARY STUDIES (Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu) UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMME (Courses effective from Academic Year 2015-16) SYLLABUS OF COURSES TO BE OFFERED Core Courses, Elective Courses & Ability Enhancement Courses Disclaimer: The CBCS syllabus is uploaded as given by the Faculty concerned to the Academic Council. The same has been approved as it is by the Academic Council on 13.7.2015 and Executive Council on 14.7.2015. Any query may kindly be addressed to the concerned Faculty. Undergraduate Programme Secretariat Preamble The University Grants Commission (UGC) has initiated several measures to bring equity, efficiency and excellence in the Higher Education System of country. The important measures taken to enhance academic standards and quality in higher education include innovation and improvements in curriculum, teaching-learning process, examination and evaluation systems, besides governance and other matters. The UGC has formulated various regulations and guidelines from time to time to improve the higher education system and maintain minimum standards and quality across the Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) in India. The academic reforms recommended by the UGC in the recent past have led to overall improvement in the higher education system. However, due to lot of diversity in the system of higher education, there are multiple approaches followed by universities towards examination, evaluation and grading system. While the HEIs must have the flexibility and freedom in designing the examination and evaluation methods that best fits the curriculum, syllabi and teaching–learning methods, there is a need to devise a sensible system for awarding the grades based on the performance of students. -

Muslim Personal Law in India a Select Bibliography 1949-74

MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1949-74 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Library Science, 1973-74 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIEVCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH. Ishrat All QureshI ROLL No. 5 ENROLMENT No. C 2282 20 OCT 1987 DS1018 IMH- ti ^' mux^ ^mCTSSDmSi MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA -19I4.9 « i97l<. A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRSMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DESIEE OF MASTER .OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, 1973-7^ DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH ,^.SHRAT ALI QURESHI Roll No.5 Enrolment Nb.C 2282 «*Z know tbt QUaa of Itlui elaiJi fliullty for tho popular sohools of Mohunodan Lav though thoj noror found it potslbla to dany the thaorotloal peasl^Ultj of a eoqplota Ijtlhad. Z hava triad to azplain tha oauaaa ¥hieh,in my opinion, dataminad tbia attitudo of tlia laaaaibut ainca thinga hcra ehangad and tha world of Ulan is today oonfrontad and affaetad bj nav foroaa sat fraa by tha extraordinary davalopaant of huaan thought in all ita diraetiona, I see no reason why thia attitude should be •aintainad any longer* Did tha foundera of our sehools ever elala finality for their reaaoninga and interpreti^ tionaT Navar* The elaii of tha pxasaat generation of Muslia liberala to raintexprat the foundational legal prineipleay in the light of their ovn ej^arla^oe and the altered eonditlona of aodarn lifs is,in wj opinion, perfectly Justified* Xhe teaehing of the Quran that life is a proeasa of progressiva eraation naeaaaltatas that eaoh generation, guided b&t unhampered by the vork of its predeoessors,should be peraittad to solve its own pxbbleas." ZQ BA L '*W« cannot n»gl«ct or ignoi* th« stupandoits vox^ dont by the aarly jurists but «• cannot b« bound by it; v« must go back to tha original sources 9 th« (^ran and tba Sunna. -

Ksg:Newspaper Crux 7Th January, 2021

KSG:NEWSPAPER CRUX 7TH JANUARY, 2021 NEWSPAPER HIGHLIGHTS NATIONAL CENTRE FOR SEISMOLOGY(NCS) Karnataka Chief Minister B.S. 1.NCS has started a geophysical survey over the Delhi Yediyurappa laid the region for accurate assessment of seismic hazards, foundation stone for the ‘New following tremors last year. Anubhava Mantapa’ in 2.Measuremnets are being conducted across three major Basavakalyan, the place where seismic sources:Mahendragarh-Dehradun Fault, Sohna 12th century poet philosopher Fault and Mathura Fault. Basaveshwara lived for most of 3.NCS, under Ministry of Earth Science, is the nodal his life. agency for monitoring of earthquake activity in the country. A committee would be constituted under Minister of CONFLICT OVER NILE State for Home G. Kishan Reddy 1.Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt have recently agreed to to find an appropriate solution resume negotiations to resolve their decade-long complex to the issues related to dispute over the Grand Renaissance Dam hydropower language, culture and project in the Horn of Africa. conservation of land in the 2.Horn of Africa is the easternmost extension of Union Territory of Ladakh, the African land and includes the region that is home to Home Ministry said in a the countries of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and statement. Somalia, whose cultures have been linked throughout their long history. Avian flu has been reported at 3.The Nile, Africa’s longest river, has been at the center of 12 epicentres in four States — a decade-long complex dispute involving several countries Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, that are dependent on the river’s waters. Himachal Pradesh and Kerala. -

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

Hoosiers and the American Story Chapter 3

3 Pioneers and Politics “At this time was the expression first used ‘Root pig, or die.’ We rooted and lived and father said if we could only make a little and lay it out in land while land was only $1.25 an acre we would be making money fast.” — Andrew TenBrook, 1889 The pioneers who settled in Indiana had to work England states. Southerners tended to settle mostly in hard to feed, house, and clothe their families. Every- southern Indiana; the Mid-Atlantic people in central thing had to be built and made from scratch. They Indiana; the New Englanders in the northern regions. had to do as the pioneer Andrew TenBrook describes There were exceptions. Some New Englanders did above, “Root pig, or die.” This phrase, a common one settle in southern Indiana, for example. during the pioneer period, means one must work hard Pioneers filled up Indiana from south to north or suffer the consequences, and in the Indiana wilder- like a glass of water fills from bottom to top. The ness those consequences could be hunger. Luckily, the southerners came first, making homes along the frontier was a place of abundance, the land was rich, Ohio, Whitewater, and Wabash Rivers. By the 1820s the forests and rivers bountiful, and the pioneers people were moving to central Indiana, by the 1830s to knew how to gather nuts, plants, and fruits from the northern regions. The presence of Indians in the north forest; sow and reap crops; and profit when there and more difficult access delayed settlement there. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Habib Tanvir’s Naya Theatre: Towards the Revival of Folk Theatre Sangeeta Mishra, Ph.D. Scholar Dept. of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies University of Delhi Abstract During 1943- 1944, the rise of IPTA (Indian People‟s theatre Association) brought life to the theatre in many regions of the country giving it a new strength and direction. This movement made a significant effort to bring theatre close to the people and make them socially relevant in terms of the content. Habib Tanvir, among others has been a part of this movement. Since the beginning of 1960s, Habib Tanvir started his attempts to forge a new indigenous form of theatre for which he went to Sanskrit and traditional theatre. This paper attempts to explore the salient features of Habib Tanvir‟s Naya Theatre and his plays as a medium to study the different dimension of folk and indigenous forms that could relate to common man‟s life and hence highlight the social and political impact. Keywords: Indian theatre; IPTA; Naya Theatre; theatre for the people; Chhattisgarhi tribes INTRODUCTION As B.V Karanth states: “Whenever we look for our own identity or legacy, our Quest automatically ends at the same emotional destination- there- at the folk theatre.”i Habib Tanvir, a popular Hindi playwright, a theatre director, a poet, an actor, was the pioneer of a very special genre of Hindi theatre and was known for his works with the Chhattisgarhi tribes, at Naya Theatre, Bhopal, 1964. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

Dr Rajendra Mehta.Pdf

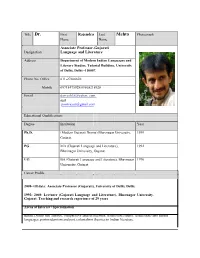

Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Associate Professor-Gujarati Designation Language and Literature Address Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, Tutorial Building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 09718475928/09868218928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com and [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Associate Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 29 years Areas of Interest / Specialization Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses (certificate, diploma, advanced diploma) 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Tragedy in Indian literature, Ascetics and poetics 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Introduction to an Indian language- Gujarati Research Guidance M.Phil. student -12 Ph.D. student - 05 Details of the Training Programmes attended: Name of the Programme From Date To Date Duration Organizing Institution -

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(S): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(s): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 51, No. 2 (May, 1999), pp. 127-147 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068647 Accessed: 13/06/2009 19:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theatre Journal. http://www.jstor.org Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Kathryn Hansen Over the last century the once-spurned female performer has been transformed into a ubiquitous emblem of Indian national culture.