Project Rebirth Seminar Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations In

Capturing the Void: The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations in Documentary Films on September 11, 2001 Jodye D. Whitesell Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of Film Studies Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Peterson October 24, 2012 Committee Members: Dr. Jennifer Peterson, Film Studies Dr. Melinda Barlow, Film Studies Dr. Carole McGranahan, Anthropology Table of Contents: Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Part I: The Progression of Documentary Film Production………………………………… 9 Part II: September 11, 2001….…………………………………………………………….. 15 Part III: The Immediate Role of the Media………………………………………………... 18 Part IV: Collective Memories and the Media,,,……………………………………………. 25 Part V: The Turn Towards Documentary…………………………………….……………. 34 (1) Providing a Historical Record…………………………………….……………. 36 (2) Challenging the Official Story…………………………………………………. 53 (3) Memorializing the Fallen………………………………………………………. 61 (4) Recovering from the Trauma…………………………………………………... 68 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 79 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………... 83 2 Abstract: Documentary films have long occupied a privileged role among audiences as the purveyors of truth, offering viewers accurate reproductions of reality. While this classification is debatable, the role of documentaries as vehicles for collective memory is vital to the societal reconstructions of historical events, a connection that must be understood in order to properly assign meaning to the them. This thesis examines this relationship, focusing specifically on the documentaries produced related to trauma (in this case the September 11 attacks on the United States) as a means to enhance understanding of the role these films play in the lives and memories of their collective audiences. Of the massive collection of 9/11 documentaries produced since 2001, twenty-three were chosen for analysis based on national significance, role as a representative of a category (e.g. -

Our Changing Identity

Being American: Our Changing Identity By Nathan A. Bronstein An Honors Capstone for General University Honors (Spring 2012) Capstone Advisor: Gary Weaver School of International Service 1 Table of Contents 3, Introduction 9, Chapter 1: Culture is an Orange 15, Chapter 2: What… Erm… Who... is American 39, Chapter 3: When in Doubt, Dawn Your Cape 56, Chapter 4: This Land is My Land and Your Land 67, Chapter 5: Technology and us… are In a Relationship 77, Chapter 6: Our Moment 87, Chapter 7: Ah, That’s my Fancy Private School Learnin’ 95, Chapter 8: The Civically Engaged Generation 111, Chapter 9: You’re Hearing Me, Not Listening! 117, Chapter 10: Have Faith 124, Chapter 11: Up, Up, and Abroad! 130, Chapter 12: Renewable Family 137, Chapter 13: Looking Ahead, Now and Then 147, References 2 Introduction: “We go forth all to seek America. And in seeking we create her.” –Waldo Frank I was wearing my Captain America sweatshirt in near 100° weather and I felt good. It was red, white and blue day at the summer camp I have been working at almost every summer since I was 16. The same camp I had attended for five years from 8 to 12. My “leadership” professor, yes, I have a leadership professor, told me that this camp is like cookies and milk; something comforting from my childhood, but something I should move on from. Well… at 22 years of age I love cookies in milk; but I digress. The sweatshirt had been given to me as a Christmas gift from my Student Government staff back at American University in Washington DC. -

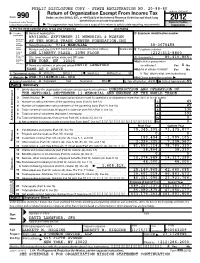

2012 Form 990 Or 990‐EZ

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY - STATE REGISTRATION NO. 20-88-80 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2012 Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service | The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2012 calendar year, or tax year beginning and ending B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable: NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL & MUSEUM Address change AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER FOUNDATION,INC Name change Doing Business As 9/11 MEMORIAL 38-3678458 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Termin- ated ONE LIBERTY PLAZA, 20TH FLOOR (212)312-8800 Amended return City, town, or post office, state, and ZIP code G Gross receipts $ 85,416,865. Applica- tion NEW YORK, NY 10006 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer:DAVID LANGFORD for affiliates? Yes X No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )§ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: | WWW.911MEMORIAL.ORG H(c) Group exemption number | K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other | L Year of formation: 2003 M State of legal domicile: NY Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF THE NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL AND MUSEUM AT THE WORLD TRADE 2 Check this box | if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Amended Final Action Plan As Approved by HUD April 3, 2020

Amended Final Action Plan As Approved by HUD 4/03/2020, Revised 12/17/2020 LOWER MANHATTAN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Amended Final Action Plan For Lower Manhattan Disaster Recovery and Rebuilding Efforts Overview The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) has prepared this Amended Final Action Plan with regards to the $2 billion federal appropriation for the World Trade Center disaster recovery and rebuilding efforts administered by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). LMDC has received additional funding through a $783,000,000 federal appropriation from HUD for damaged properties and businesses (including the restoration of utility infrastructure) as well as economic revitalization related to the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center (WTC). Partial Action Plans detailing the expenditure of the other funds from the $2.783 billion appropriation and are viewable on the LMDC website at http://renewnyc.com/FundingInitiatives/PartialActionPlans.aspx. Amended Allocations Original Amended Allocations Approved by Allocation Allocations Revised HUD 12/6/06 Approved by 2/21/17- 4/03/2020 Revised HUD 12/18/15 6/12/17 3/8/18 Revised 2/27/13 and 10/14/16 & 3/8/19 12/17/2020 I. WTC Memorial and Cultural A.Reserve Fund $44,000,000 $44,000,000 $44,000,000 $44,000,000 B.WTC Construction Coordination $1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000 $1,000,000 C. WTC Memorial Tribute in Light $810,000 $810,000 $810,000 $810,000 Subtotal $45,810,000 $45,810,000 $45,810,000 $45,810,000 II. Affordable Housing $12,000,000 $12,000,000 $12,800,000 $12,800,000 III. -

Sacred Secular Relics: World Trade Center Steel in Off-Site 9/11 Memorials in the United States

SACRED SECULAR RELICS: WORLD TRADE CENTER STEEL IN OFF-SITE 9/11 MEMORIALS IN THE UNITED STATES by Senem Guler-Biyikli B.A. in Business Administration, Koç University, 2008 M.A. in Anatolian Civilizations & Cultural Heritage Management, Koç University, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Senem Guler-Biyikli It was defended on December 5, 2016 and approved by Bryan K. Hanks, Associate Professor, Anthropology Laura C. Brown, Assistant Professor, Anthropology Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art & Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Robert M. Hayden, Professor, Anthropology ii Copyright © by Senem Guler-Biyikli 2017 iii SACRED SECULAR RELICS: WORLD TRADE CENTER STEEL IN OFF-SITE 9/11 MEMORIALS IN THE UNITED STATES Senem Guler-Biyikli, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 This dissertation analyzes material practices in the commemoration of violence and trauma through a focus on the memorialization of World Trade Center (WTC) structural steel across the United States to form hundreds of local 9/11 monuments. Less than one percent of the steel artifacts collected from the WTC site was reconfigured as sacred relics and became the focal elements of local memorials, while the rest was sold and recycled as scrap. Based on ten months of fieldwork at such local memorials primarily in the Northeastern United States, the study documents the artifacts’ memorialization, and discusses the socio-cultural factors involved in their transformation from rubble to sacred relics. -

Additional Resources

Additional Resources The list below contains only a small portion of the many resources that are now available relating to the content in this curriculum: terrorist attacks before and since September 11, 2001, the September 11th attacks, There are also articles offering expert advice on working with children and trauma, conflict resolution and peacemaking efforts, and educational materials for teaching about these topics. Good web quest will harvest a large number of possibilities for you. However, the sources listed below will offer you a good places to begin your search for additional information, advice, and materials. Museums Liberty Science Center – http://www.lsc.org/lsc/ourexperiences/exhibits/skyscraper - Skyscraper! provides an unprecedented look at the planning, design, engineering and technology of these amazing structures – and their impact on human culture, the environment and even local weather patterns. Attendees can walk a steel girder high above the exhibit floor, face down jet-powered hurricane force winds to test a building design, or take a quiet moment to reflect on the destruction of the World Trade Center, Skyscraper! leaves one with a new appreciation – and completely altered view – of the impressive New York City skyline that surrounds us. Kidsbridge Tolerance Museum – http://www.kidsbridgemuseum.org - The Kidsbridge Tolerance Museum is located at The College of New Jersey. The museum and the college have collaborated to create a partnership to teach diversity appreciation and character education to elementary school children. The museum provides a learning lab experience and is open to bookings for elementary and middle school age groups. National September 11 Memorial and Museum – http://www.national911memorial.org. -

TAPE # LC006 Larry Courtney - IV JIM WHITAKER, Producer/Director PROJECT REBIRTH

Transcription by G. Tamblyn (818) 758-9171 TAPE # LC006 Larry Courtney - IV JIM WHITAKER, Producer/Director PROJECT REBIRTH 06.01.00 PICTURE UP (OFF CAMERA REMARKS) JW: How are your daughter and son? 06.03.19 LARRY : They’re doing well, they’re doing very well. Uh, my son, uh, my oldest son whom you didn't meet, uh, he was there that day, though uh, September 11th. (~I~) 06.03.30 Uh, he and his wife are expecting their first child any day now. And uh, they’re in Lake Tahoe, love it out there. And uh, so I’m going to California the last week of July. I thought let them get a little bit adjusted to this baby before I drop in. And uh, (~I~) (OFF CAMERA REMARKS) 06.04.04 LARRY : Oh, I you know, having had the three uh, it was nice to have somebody come later, so. Uh, and I’ll spend time with my daughter. She’s still in California, loves it. She just got engaged, so. Uh, I said, well, why don't you plan a wedding while I’m there so (LAUGHS) I won’t have to make another trip out here. 06.04.30 But there, I think they’re planning to get married next May. So I’ll go back to California in May. But and then uh. JW: And you know him? (SIMULTANEOUS CONVERSATION) PROJECT REBIRTH P.O. Box 901 Peck Slip Station New York, NY 10727-0910 212-346-1482 PROJECT REBIRTH: - TAPE # - JW, Pro/dir - ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 06.04.43 LARRY : When I was out there right after uh, let’s see I was out there at the end of October, 2001. -

2012 Year End Update Message from Mayor Michael R

2012 Year end Update Message FROM MaYor Michael r. BlooMBerg Chair of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum Within its first year of opening to the public, the National September 11 Memorial became one of the most visited sites in New York City and the nation. Millions of visitors representing all 50 states and more than 175 nations have come to the Memorial to remember and reflect on all those we lost in the attacks on the World Trade Center. At the heart of the World Trade Center site, the 9/11 Memorial serves as a powerful tribute to the 2,983 innocent men, women, and children who perished in the attacks on September 11, 2001 and February 26, 1993. People from across the nation and the world have come to lower Manhattan to honor their memories by reading the names etched along the two memorial pools. As visitors experience this unprecedented tribute, many contemplate both the unspeakable tragedy and remarkable heroism of that day—and find hope in the renewal that surrounds them. The 9/11 Memorial would not have been possible without the generosity of thousands of individuals, businesses, and organizations. It is also because of this outstanding support, as well as strong partnerships with Governor Andrew Cuomo, Governor Chris Christie, and the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, that we will be able to open the 9/11 Memorial Museum. The Museum is critical to our mission of sharing the story of the attacks that changed our world and ensuring that it is remembered by all future generations. -

Learning from the Challenges of Our Times: Global Security, Terrorism, and 9/11 in the Classroom

LEARNING FROM THE CHALLENGES OF OUR TIMES: Global Security, Terrorism, and 9/11 in the Classroom A New Curricular Initiative for Students in Grades K-12 LEARNING FROM THE CHALLENGES OF OUR TIMES: Global Security, Terrorism, and 9/11 in the Classroom We are most grateful for the generous grants from The Investors Savings Bank Foundation that made the publication of this curriculum possible. July 2011 Dear Educator: The 4 Action Initiative, a collaboration of Families of September 11, Liberty Science Center and The New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education, is pleased to present a new curriculum, Learning from the Challenges of Our Times: Global Security, Terrorism and 9/11 in the Classroom. New Jersey teachers can visit http://www. state.nj.us/education/holocaust for NJ Core Curriculum Standards related to the lesson plans. All educators are encouraged to check there for updates and additional resources. At the 4 Action Initiative inaugural conference in July of 2008, Governor Tom Kean spoke eloquently about the need to educate students about global security and the legacy of September 11th saying, “education is a must to eliminate these tragedies in the future and to educate all as to what happened on 9/11.” The lessons contained in this curriculum were developed, piloted in over 60 New Jersey school districts, revised and refined by curriculum developers and the 4 Action Initiative team. While there are lessons for all grade levels, teachers should adjust the lessons for their classes, always taking into account the ages of their students, the potentially traumatic nature of some lessons as they refer to violence, terrorism, and the tragedy of the day (9/11). -

World Trade Center Site Memorial Center Advisory Committee Draft Recommendations for the Memorial Center

WORLD TRADE CENTER SITE MEMORIAL CENTER ADVISORY COMMITTEE DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE MEMORIAL CENTER PREFACE In January 2004, LMDC unveiled the winning World Trade Center Site Memorial design, Reflecting Absence, by Michael Arad and Peter Walker. LMDC and Studio Daniel Libeskind, working in collaboration with the memorial design team of Michael Arad and Peter Walker, established a new location for a below grade Memorial Center dedicated to the events of September 11, 2001, and February 26, 1993 at the southwest corner of the memorial site. In April 2004, LMDC announced the formation of a Memorial Center Advisory Committee to make recommendations for the Memorial Center. The Advisory Committee— victims’ family members, residents, survivors, first responders, his- torians, preservationists, and curators—visited the WTC memorial site and Hangar 17 at JFK Airport, where many arti- facts from the World Trade Center are being stored, and met with professionals to learn from their experience in creating exhibitions. The Advisory Committee also reviewed an expansive list of archives and resources relating to the attacks. Through a series of facilitated meetings, the Advisory Committee produced these draft recommendations. During the course of their meetings, members of the Advisory Committee debated a number of issues. One issue was the breadth of the Memorial Center’s subject matter, particularly with respect to the terrorists and their ideology. The Committee agreed that some information regarding the terrorists and who they were should be provided, but refrained from recommend- ing information beyond the facts. Another issue was the level of specificity to give in relation to the inclusion of artifacts with- in the Memorial Center. -

2018 Nagc Annual Symposium Course Catalog

1 2018 NAGC ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM COURSE CATALOG June 28-30, 2018 | San Antonio, TX Table of Contents Thursday • June 28, 2018 • 9:00am to 10:00am .................................................................................................................... 5 Opening Plenary: To the Heart: Body Language Insights for Working with Grieving Children .......................................... 5 Thursday • June 28, 2018 • 4:30pm to 5:30pm ...................................................................................................................... 6 Large Session: Creative Ideas to Engage, Educate, ............................................................................................................. 6 and Support Grieving Children, Teens, and Families .......................................................................................................... 6 Friday • June 29, 2018 • 3:30pm to 5:00pm ........................................................................................................................... 7 Large Session: The Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model (CBEM): A public health tool for translating prevalence into action ........................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Saturday • June 30, 2018 • 11:00am to 12:30pm .................................................................................................................. 9 Closing Session: The Symposium is Ending, But We’ve -

September 11 Attacks

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search Wikipedia September 11 attacks From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page "9/11" redirects here. For the date September 11, see September 11. For the date November 9, Contents see November 9. Featured content For the emergency number, see 9-1-1. Current events For other uses, see September 11 attacks (disambiguation). Random article The September 11 attacks (also referred to as 9/11)[nb 1] Donate to Wikipedia September 11 attacks Wikipedia store were a series of four coordinated terrorist attacks by the Part of Terrorism in the United States Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda on the United States on Interaction the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001. The attacks Help killed 2,996 people, injured over 6,000 others, and caused About Wikipedia at least $10 billion in infrastructure and property Community portal [2][3] Recent changes damage. Contact page Four passenger airliners operated by two major U.S. passenger air carriers (United Airlines and American Tools Airlines)—all of which departed from airports in the What links here Related changes northeastern United States bound for California—were Upload file hijacked by 19 al-Qaeda terrorists. Two of the planes, Special pages American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175, Permanent link were crashed into the North and South towers, Page information respectively, of the World Trade Center complex in New Wikidata item open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Wikidata item York City.