How to Become a Post-Dog. Animals in Transhumanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

Citizen Cyborg.” Citizen a Groundbreaking Work of Social Commentary, Citizen Cyborg Artificial Intelligence, Nanotechnology, and Genetic Engineering —DR

hughes (continued from front flap) $26.95 US ADVANCE PRAISE FOR ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE NANOTECHNOLOGY GENETIC ENGINEERING MEDICAL ETHICS INVITRO FERTILIZATION STEM-CELL RESEARCH $37.95 CAN citizen LIFE EXTENSION GENETIC PATENTS HUMAN GENETIC ENGINEERING CLONING SEX SELECTION ASSISTED SUICIDE UNIVERSAL HEALTHCARE human genetic engineering, sex selection, drugs, and assisted In the next fifty years, life spans will extend well beyond a century. suicide—and concludes with a concrete political agenda for pro- cyborg Our senses and cognition will be enhanced. We will have greater technology progressives, including expanding and deepening control over our emotions and memory. Our bodies and brains “A challenging and provocative look at the intersection of human self-modification and human rights, reforming genetic patent laws, and providing SOCIETIES MUST RESPOND TO THE REDESIGNED HUMAN OF FUTURE WHY DEMOCRATIC will be surrounded by and merged with computer power. The limits political governance. Everyone wondering how society will be able to handle the coming citizen everyone with healthcare and a basic guaranteed income. of the human body will be transcended, as technologies such as possibilities of A.I. and genomics should read Citizen Cyborg.” citizen A groundbreaking work of social commentary, Citizen Cyborg artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and genetic engineering —DR. GREGORY STOCK, author of Redesigning Humans illuminates the technologies that are pushing the boundaries of converge and accelerate. With them, we will redesign ourselves and humanness—and the debate that may determine the future of the our children into varieties of posthumanity. “A powerful indictment of the anti-rationalist attitudes that are dominating our national human race itself. -

Transhumanism Between Human Enhancement and Technological Innovation*

Transhumanism Between Human Enhancement and Technological Innovation* Ion Iuga Abstract: Transhumanism introduces from its very beginning a paradigm shift about concepts like human nature, progress and human future. An overview of its ideology reveals a strong belief in the idea of human enhancement through technologically means. The theory of technological singularity, which is more or less a radicalisation of the transhumanist discourse, foresees a radical evolutionary change through artificial intelligence. The boundaries between intelligent machines and human beings will be blurred. The consequence is the upcoming of a post-biological and posthuman future when intelligent technology becomes autonomous and constantly self-improving. Considering these predictions, I will investigate here the way in which the idea of human enhancement modifies our understanding of technological innovation. I will argue that such change goes in at least two directions. On the one hand, innovation is seen as something that will inevitably lead towards intelligent machines and human enhancement. On the other hand, there is a direction such as “Singularity University,” where innovation is called to pragmatically solving human challenges. Yet there is a unifying spirit which holds together the two directions and I think it is the same transhumanist idea. Keywords: transhumanism, technological innovation, human enhancement, singularity Each of your smartphones is more powerful than the fastest supercomputer in the world of 20 years ago. (Kathryn Myronuk) If you understand the potential of these exponential technologies to transform everything from energy to education, you have different perspective on how we can solve the grand challenges of humanity. (Ray Kurzweil) We seek to connect a humanitarian community of forward-thinking people in a global movement toward an abundant future (Singularity University, Impact report 2014). -

Iaj 10-3 (2019)

Vol. 10 No. 3 2019 Arthur D. Simons Center for Interagency Cooperation, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas FEATURES | 1 About The Simons Center The Arthur D. Simons Center for Interagency Cooperation is a major program of the Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc. The Simons Center is committed to the development of military leaders with interagency operational skills and an interagency body of knowledge that facilitates broader and more effective cooperation and policy implementation. About the CGSC Foundation The Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc., was established on December 28, 2005 as a tax-exempt, non-profit educational foundation that provides resources and support to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in the development of tomorrow’s military leaders. The CGSC Foundation helps to advance the profession of military art and science by promoting the welfare and enhancing the prestigious educational programs of the CGSC. The CGSC Foundation supports the College’s many areas of focus by providing financial and research support for major programs such as the Simons Center, symposia, conferences, and lectures, as well as funding and organizing community outreach activities that help connect the American public to their Army. All Simons Center works are published by the “CGSC Foundation Press.” The CGSC Foundation is an equal opportunity provider. InterAgency Journal FEATURES Vol. 10, No. 3 (2019) 4 In the beginning... Special Report by Robert Ulin Arthur D. Simons Center for Interagency Cooperation 7 Military Neuro-Interventions: The Lewis and Clark Center Solving the Right Problems for Ethical Outcomes 100 Stimson Ave., Suite 1149 Shannon E. -

Nietzsche and Transhumanism Nietzsche Now Series

Nietzsche and Transhumanism Nietzsche Now Series Cambridge Scholars Publishing Editors: Stefan Lorenz Sorgner and Yunus Tuncel Editorial Board: Keith Ansell-Pearson, Rebecca Bamford, Nicholas Birns, David Kilpatrick, Vanessa Lemm, Iain Thomson, Paul van Tongeren, and Ashley Woodward If you are interested in publishing in this series, please send your inquiry to the editors Stefan Lorenz Sorgner at [email protected] and Yunus Tuncel at [email protected] Nietzsche and Transhumanism: Precursor or Enemy? Edited by Yunus Tuncel Nietzsche and Transhumanism: Precursor or Enemy? Series: Nietzsche Now Edited by Yunus Tuncel This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Yunus Tuncel and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7287-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7287-4 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Yunus Tuncel Part I Chapter One ............................................................................................... 14 Nietzsche, the Overhuman, and Transhumanism Stefan Lorenz Sorgner -

Technological Enhancement and Criminal Responsibility1

THIS VERSION DOES NOT CONTAIN PAGE NUMBERS. PLEASE CONSULT THE PRINT OR ONLINE DATABASE VERSIONS FOR PROPER CITATION INFORMATION. ARTICLE HUMANS AND HUMANS+: TECHNOLOGICAL ENHANCEMENT AND CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY1 SUSAN W. BRENNER2 I. INTRODUCTION [G]radually, the truth dawned on me: that Man had not remained one species . .3 It has been approximately 30,000 years since our species—Homo sapiens sapiens—shared the earth with another member of the genus Homo.4 I note 1 It was only after I decided to use Humans+ as part of the title for this article that I discovered the very similar device used by the transhumanist organization, Humanity+. See Mission, HUMANITY PLUS, http://humanityplus.org/about/mission/ (last visited Feb. 25, 2013). 2 NCR Distinguished Professor of Law & Technology, University of Dayton School of Law, Dayton, Ohio, USA. Email: [email protected]. 3 H.G. WELLS, THE TIME MACHINE 59 (Frank D. McConnell ed. 1977). 4 See GRAHAM CONNAH, FORGOTTEN AFRICA: AN INTRODUCTION TO ITS ARCHAEOLOGY 7–16 (2004) (supporting emergence of genus Homo in Africa); CHRIS GOSDEN, PREHISTORY: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION xiv–xv, 39–42 (2003) (summarizing rise of Homo sapiens sapiens). “Taxonomy,” or “the study of classification,” involves the process of sorting plants and animals into categories, including species. STEPHEN JAY GOULD, EVER SINCE DARWIN: REFLECTIONS IN NATURAL HISTORY 231 (1977). The species Homo sapiens includes Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans) as well as several “archaic” members of the species. See, e.g., William Howells, Getting Here: The Story of Human Evolution 122– 23 (Washington, DC: Compass Press 1993). See also R.A. -

Ray Kurzweil Reader Pdf 6-20-03

Acknowledgements The essays in this collection were published on KurzweilAI.net during 2001-2003, and have benefited from the devoted efforts of the KurzweilAI.net editorial team. Our team includes Amara D. Angelica, editor; Nanda Barker-Hook, editorial projects manager; Sarah Black, associate editor; Emily Brown, editorial assistant; and Celia Black-Brooks, graphics design manager and vice president of business development. Also providing technical and administrative support to KurzweilAI.net are Ken Linde, systems manager; Matt Bridges, lead software developer; Aaron Kleiner, chief operating and financial officer; Zoux, sound engineer and music consultant; Toshi Hoo, video engineering and videography consultant; Denise Scutellaro, accounting manager; Joan Walsh, accounting supervisor; Maria Ellis, accounting assistant; and Don Gonson, strategic advisor. —Ray Kurzweil, Editor-in-Chief TABLE OF CONTENTS LIVING FOREVER 1 Is immortality coming in your lifetime? Medical Advances, genetic engineering, cell and tissue engineering, rational drug design and other advances offer tantalizing promises. This section will look at the possibilities. Human Body Version 2.0 3 In the coming decades, a radical upgrading of our body's physical and mental systems, already underway, will use nanobots to augment and ultimately replace our organs. We already know how to prevent most degenerative disease through nutrition and supplementation; this will be a bridge to the emerging biotechnology revolution, which in turn will be a bridge to the nanotechnology revolution. By 2030, reverse-engineering of the human brain will have been completed and nonbiological intelligence will merge with our biological brains. Human Cloning is the Least Interesting Application of Cloning Technology 14 Cloning is an extremely important technology—not for cloning humans but for life extension: therapeutic cloning of one's own organs, creating new tissues to replace defective tissues or organs, or replacing one's organs and tissues with their "young" telomere-extended replacements without surgery. -

Better Living Through Transhumanism George Dvorsky

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 19(1) – September 2008 Better Living through Transhumanism George Dvorsky www.betterhumans.com Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 19 Issue 1 – September 2008 - pgs 62-66 http://jetpress.org/v19/dvorsky.htm Abstract A growing number of people are turning to transhumanism, which aims to promote and encourage human enhancement through the application of science and technology. They maintain that this is a good thing, and that we should encourage and work towards the attainment of a posthuman condition. Not ones to dwell on the future while passively waiting for it to happen, trashumanists engage in foresight, activist and promotional activities. Just as significantly, the day-to-day lifestyle choices of transhumanists reflect anticipated change. Transhumanism is in many respects a burgeoning lifestyle choice and cultural phenomenon. More than just a philosophy and social movement, transhumanism is for many a way of life. Some experts believe that all genetic-based diseases will be eliminated by 2030. The widespread application of genetic and other technologies, it is thought, may also result in significant increases to human intelligence, memory, physical health and strength. Some expect the achievement of indefinite lifespans this century and believe that immortals already walk among us. Researchers suspect that the development of strong nanotechnology in the coming decades will result in molecular assemblers that effectively function like Star Trek replicators. A number of experts are hopeful that medical nanotechnology will be used to revive those who are preserved in cryonic stasis. -

![Sample Chapter [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7677/sample-chapter-pdf-2177677.webp)

Sample Chapter [PDF]

THE PHILOSOPHY OF TRANSHUMANISM This page intentionally left blank THE PHILOSOPHY OF TRANSHUMANISM ACriticalAnalysis BENJAMIN ROSS University of North Texas, USA United Kingdom – North America – Japan – India Malaysia – China Emerald Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2020 © 2020 Benjamin Ross Published under exclusive licence by Emerald Publishing Limited Reprints and permissions service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters’ suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-83982-625-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-83982-622-1 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-83982-624-5 (Epub) CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Redesigning Humans 5 1.1. Transhumanist Philosophy I: Summoning the Posthuman 7 1.2. Transhumanist Philosophy II: Epistemological Certainty 13 1.3. Resisting Transhumanism: Bioconservative Views 18 1.4. The Language of Enhancement through the Lens of Automation 25 2. Engaging with Transhumanism 37 2.1. -

Linköping University Electronic Press

Linköping University Electronic Press Book Chapter Proceedings from the Societas Ethica Annual Conference 2011, The Quest for perfection. The Future of Medicine/Medicine of the future, August 25-28, 2011, Universita della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano, Switzerland Göran Collste and Arne Manzeschke Linköping Electronic Conference Proceedings, 1650-3686 (print), 1650-3740 (online), No. 74 Available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-88089 Proceedings from the Societas Ethica Annual Conference 2011, The Quest for perfection. The Future of Medicine/Medicine of the future August 25–28, 2011, Universita della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano, Switzerland Editors Göran Collste and Arne Manzescheke Societas Ethica Annual Conferens, Issue 48 Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for non- commercial research and educational purposes. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law, the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. -

Making Humanity New with Technology Stephen Goundrey-Smith

Making Humanity New with Technology Stephen Goundrey-Smith PhD Student – Department of Theology & Religion What is Transhumanism? • Transhumanism is a philosophical movement concerned with developing human life beyond its current form and limitations using biomedical technologies. • A definition of transhumanism - Philosophies of life…that seek the continuation and acceleration of the evolution of intelligent life beyond its current human form and human limitations by means of science, technology, guided by life-promoting principles and values” - Max More • Why change being human? a) to make life feel better and live it how you want, b) to make human beings better, c) to prevent extinction. The Transhumanism Movement • World Transhumanist Association (WTA) formed in 1998, by Nicholas Bostrom and David Pearce. • Many transhumanism advocates in North America and increasingly in western Europe. • Advocates of transhumanism are a “broad church” – consisting of philosophers, scientists, computer/technology specialists and many others. • The Transhumanist Declaration sets out the key principles of transhumanism- see https://humanityplus.org/philosophy/transhumanist-declaration/ A Potted History of Human Perfectibility (1) Immortality and perfection have been human concerns since time immemorial: • In philosophy – Plato, Aristotle etc • In religion - Christianity (resurrection (eternal) life and renewal of creation). • In intellectual/cultural life – the Renaissance, humanism (the philosophical and creative genius of the human mind) & the “uomo universale” - the perfect person combining intellectual and physical excellence, who could function well in virtually any situation…. A Potted History of Human Perfectibility (2) • Renaissance writer, Pico della Mirandola - Oration on the Dignity of Man - has been described as a proto-transhumanist. • Enlightenment – human sufficiency and social, educational, cultural “progress”. -

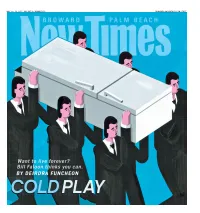

MAY 14 – 20, 2015 | VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 29 BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM I FREE NBROWARD PALM BEACH ® BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM ▼ Contents 2450 HOLLYWOOD BLVD., STE

MAY 14 – 20, 2015 | VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 29 BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM I FREE NBROWARD PALM BEACH ® BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM ▼ Contents 2450 HOLLYWOOD BLVD., STE. 301A HOLLYWOOD, FL 33020 [email protected] 954-342-7700 VOL. 18 | NO. 29 | MAY 14-20, 2015 EDITORIAL EDITOR Chuck Strouse MANAGING EDITOR Deirdra Funcheon EDITORIAL OPERATIONS MANAGER Keith Hollar browardpalmbeach.com STAFF WRITERS Laine Doss, Ray Downs, Chris Joseph, Kyle Swenson browardpalmbeach.com MUSIC EDITOR Ryan Pfeffer ARTS & CULTURE/FOOD EDITOR Rebecca McBane CLUBS EDITOR Laurie Charles PROOFREADER Mary Louise English CONTRIBUTORS David Bader, Nicole Danna, Steve Ellman, Doug Fairall, Chrissie Ferguson, Abel Folgar, Falyn Freyman, Victor Gonzalez, Regina Kaza, Dana Krangel, Erica K. Landau, Matt Preira, Alex Rendon, Andrea Richard, Stephanie Rodriguez, Gillian Speiser, John Thomason, Tana Velen, Sara Ventiera, Lee Zimmerman ART ART DIRECTOR Miche Ratto | CONTENTS | | CONTENTS ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR Kristin Bjornsen PRODUCTION PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Lugo PRODUCTION ASSISTANT MANAGER Jorge Sesin ADVERTISING ART DIRECTOR Andrea Cruz PRODUCTION ARTIST Michael Campina ADVERTISING ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Alexis Guillen EWS | PULP EWS MARKETING DIRECTOR Morgan Stockmayer N EVENT MARKETING MANAGER CarlaChristina Thompson DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER Nathalie Batista ONLINE SUPPORT MANAGER Ryan Garcia Y | RETAIL COORDINATOR Carolina del Busto Sarah Abrahams, Ryan Pete by Illustration DA SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Peter Heumann, Kristi Kinard-Dunstan, Andrea Stern ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Michelle Beckman, Joanna Brown, Jasmany Santana Featured Stories ▼ CLASSIFIED SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Patrick Butters, Ladyane Lopez, Joel Valez-Stokes ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE Tony Lopez Cold Play GE | NIGHT+ Want to live forever? CIRCULATION A T CIRCULATION DIRECTOR Richard Lynch Bill Faloon thinks you can. S CIRCULATION ASSISTANT MANAGER Rene Garcia BUSINESS BY DEIRDRA FUNCHEON | PAGE 7 GENERAL MANAGER Russell A.