Philadelphia Tribune, 1912-41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

"Citizens in the Making": Black Philadelphians, the Republican Party and Urban Reform, 1885-1913

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Julie Davidow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Davidow, Julie, ""Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2247. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Abstract “Citizens in the Making” broadens the scope of historical treatments of black politics at the end of the nineteenth century by shifting the focus of electoral battles away from the South, where states wrote disfranchisement into their constitutions. Philadelphia offers a municipal-level perspective on the relationship between African Americans, the Republican Party, and political and social reformers, but the implications of this study reach beyond one city to shed light on a nationwide effort to degrade and diminish black citizenship. I argue that black citizenship was constructed as alien and foreign in the urban North in the last decades of the nineteenth century and that this process operated in tension with and undermined the efforts of black Philadelphians to gain traction on their exercise of the franchise. For black Philadelphians at the end of the nineteenth century, the franchise did not seem doomed or secure anywhere in the nation. -

Documenting History Bibliography Audio/Visual Collection

Documenting History Bibliography Paired with Douglas Blackmon’s, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and journalist, collegiate course Documenting History— this listing of library resources includes primary reference, historical timelines and narratives, personal secondary perspectives and anthologies of comparative literature, and some criticism of specific strategies and techniques for archival and historical research. A historical exploration of the black press and the Atlanta black publications, during the 20th century, and a special inclusion of the significant contributions from the African American, Pan African and diasporic communities documenting and reflecting the black experience. The compiled reference resources also focus on forced and convict labor in southern states, especially Georgia in the 20th century. Institutional disenfranchisements such as mass incarceration, political division, and civil and economic inequalities, and injustices, are included. Resources include call numbers, for patrons to easily inquire and obtain resources. Auburn Avenue Research Library maintains non-circulating policies of its collection; however, patrons are able to utilize materials in-house. Suggested search terms and keywords are provided to further guide patron’s research amongst Auburn Avenue Research Library and the Atlanta- Fulton Public Library catalog and digital libraries. The below Boolean Operators (AND, OR, also NOT) are simple words used to maximize search results. Forrest R. Evans Librarian II, Reference and Research [email protected] -

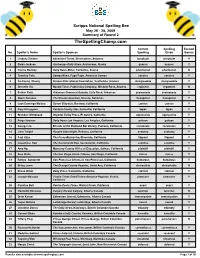

Round 2 Thespellingchamp.Com

Scripps National Spelling Bee May 26 - 28, 2009 Summary of Round 2 TheSpellingChamp.com Correct Spelling Earned No. Speller's Name Speller's Sponsor Spelling Given Bonus 1 Lindsey Zimmer Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama longitude longitude Y 2 Dylan Jackson Anchorage Daily News, Anchorage, Alaska quarrel quarrel Y 3 Tianna Beckley Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska pharmacist pharmecist N 4 Tynishia Tufu Samoa News, Pago Pago, American Samoa concise concise Y 5 So-Young Chung Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona disagreeable disagreeable Y 6 Shevelle Six Navajo Times Publishing Company, Window Rock, Arizona regiment regamont N 7 Esther Park Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas promenade promenade Y 8 Abeni Deveaux The Nassau Guardian, Nassau, Bahamas hexagonal hexagonal Y 9 Juan Domingo Malana Desert Dispatch, Barstow, California census census Y 10 Cory Klingsporn Ventura County Star, Camarillo, California topaz topaz Y 11 Brandon Whitehead Imperial Valley Press, El Centro, California oppressive oppressive Y 12 Paige Vasseur Daily News Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California pelican pelican Y 13 George Liu Friends of the Diamond Bar Library, Pomona, California reevaluate reevaluate Y 14 Liam Twight Record Searchlight, Redding, California anatomy anatomy Y 15 Paul Uzzo The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, California flippant flippant Y 16 Josephine Kao The Sacramento Bee, Sacramento, California sedative sedative Y 17 Amy Ng Monterey County Office of Education, Salinas, California plaintiff plaintiff Y 18 Alex -

Interpreting Racial Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage Benjamin Rex LaPoe II Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation LaPoe II, Benjamin Rex, "Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INTERPRETING RACIAL POLITICS: BLACK AND MAINSTREAM PRESS WEB SITE TEA PARTY COVERAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Benjamin Rex LaPoe II B.A. West Virginia University, 2003 M.S. West Virginia University, 2008 August 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction -

Moran V. Selig

Case 2:03-cv-07424-R• -CT Document 28 Filed• 03/15/04 Page 1 of 5 1 HOWARD L. GANZ (Admitted Pro Hac Vice) AMY B. REGAN (Admitted Pro Hac Vice) 2 PROSK1\.UER ROSE LLP ,.l' 1585 Broadway ~'~.~ 3 New York, NY 10036-8299 Telephone: (212) 969-3000 4 Fax: (212) 969-1900 "'-". ~ - FIlED . CtERl\:. U.s. OISTI\lCT COURT . 5 RlCHARD MARMARO SBN 91387 . '. LARY ALAN RAPPAPORT, SBN 87614 6 PROSKAUER ROSE LLP d _15m 2049 Century Park East, 32n Floor , 7 Los California 90067-3206 CENTRAL STRle OF CAUFORNIA. DEPUTY Te 557-2900 BY & .. , " ~ . ___~~~~~..,193 '1,1~ - -~- UNITED STATES DISTRlCT COURT CENTRAL DISTRlCT OF CALIFORNIA 1E.!---f1b:;lgU\R:q]:t\~ MORAN", ERNEST . Case No. LACV03-7424 R (CTx) MIKE COLBt:RN, and on behalf of all similarly Major League Baseball DEFENDANTS' STATEMENT OF UNCONTROVERTED FACTS 16 AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Plaintiffs, IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO 17 DISMISS THE COMPLAINT v. AND/OR SUMMARY 18 JUDGMENT PURSUANT TO ALLAN H. "BUD" SELIG as LOCAL RULE 56-1 19 Commissioner of Major League Baseball, et al., Date: March 15, 2004 20 Time: 10:00 A.M. Defendants Place: Courtroom 8 21 Hon. Manuel L. Real 22 23 In support of their motion to dismiss the complaint and/or for summary 24 judgment, defendants, by their attorneys, Proskauer Rose LLP, assert that the 25 following material facts are uncontroverted and respectfully request that the Court 26 adopt the following conclusions ~~r~~~~mJ~ 27 D~~~~ 28 0176/48789'()15 NYLIB 111726491 v2 Case 2:03-cv-07424-R• -CT Document 28 Filed• 03/15/04 Page 2 of 5 1 Uncontroverted Facts 2 2: 3 1. -

The Mrican American Press and the Holocaust

32 The Journal of Intergroup Relations The MricanAmerican Press and the Holocaust 1 Felecia G. Jones Ross and Sakile Kai Camara Black owned and operated newspapers represent and advocate African-Americans' interests and concerns that the mainstream media have marginalized or ignored (Huspek, 2004; Hutton, 1993; Kessler, 1984; Lacy, Stephens & Soffin, 1991; Wilson & Gutierrez, 1995; ·· ;tl Wolseley, 1990). Appealing to principles of democracy and human rights, the black press has fought against the dominant society's oppression and mistreatment of Mrican Americans in the United States but also other groups worldwide. In editorials, articles and political cartoons, black press news coverage during both world wars pointed out the hypocrisy of a nation that symbolized democratic free dom to the world yet mistreated its own citizens at home (Kornweibel, 1994; Washburn, 1986). Human rights abuses anywhere, they argued, threatened human dignity and security everywhere (Carson, 1998).i This was especially true regarding black-owned and -operated news papers' uses of the Jewish Holocaust of the 1930s and 1940s as an opportunity to expand their human rights advocacy for groups other than Mrican Americans. Although the mainstream press in the United States published vivid reports of the Nazi brutality, it did not focus on the immorality of the practices in the way the African American press did. Drawing upon two leading newspapers, we will highlight how The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier, in contrast to main stream coverage, underscored the importance of human rights as they related to issues of the Holocaust. This study thus seeks to remedy a tendency in a century's worth of academic description and analysis of the black press in the Felecia G. -

2020 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 3 by SENATORS TARVER

2020 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 3 BY SENATORS TARVER AND PEACOCK A RESOLUTION To commend The Shreveport Sun, its owners, editors, and staff, on the occasion of its one hundredth anniversary and to acknowledge its exemplary status as the oldest black weekly newspaper in the state of Louisiana. WHEREAS, the Senate of the Legislature of Louisiana proudly acknowledges The Shreveport Sun as a significant news media publishing outlet and as an effective agent for change in the Ark-La-Tex region; and WHEREAS, The Shreveport Sun shares the spotlight with notable African-American publications, both past and present; each played a major role in local politics and business affairs within their respective communities; these publications include the Louisiana Weekly (New Orleans), the Chicago Defender, the Richmond Planet, the Chicago Bee, the Miami Times, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Roanoke Tribune, the Philadelphia Tribune, the Atlanta Daily World, and the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder; and WHEREAS, in 1920, Melvin Lee (M.L.) Collins Sr., an educator and a steadfast man of vision, founded the weekly newspaper, The Shreveport Sun, the first of its kind in the community, as he sought to provide a medium against the racial oppression of the time and to provide a venue for acknowledgment of the achievements and social activities of African-Americans, who had little representation in mainstream media; and WHEREAS, he published the news events of an under-served constituency, from birth to marriage, then onto passage from life and dismissal, The Shreveport Sun acknowledged the happenings of African-American society and voiced the issues of civil rights, literacy, and economic development that included the advertisement and promotion of minority professionals and business interests; and WHEREAS, in the beginning, The Shreveport Sun served both urban and rural Page 1 of 3 SR NO. -

Primary Sources Packet

LESSON: History Unfolded: Black Press Coverage of the Holocaust HANDOUT: Primary Source Packet Use the table of contents below to read through the Historical Information on Black Newspapers and the primary sources you are assigned. TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Information on Black Newspapers 2 Assignment 1 3 Assignment 2 (two sources in this one) 7 Assignment 3 16 Assignment 4 20 Assignment 5 25 Assignment 6 30 Assignment 7 35 Primary Sources | 1 of 39 LESSON: History Unfolded: Black Press Coverage of the Holocaust HANDOUT: Primary Source Packet Historical Information on Black Newspapers The following descriptions provide background information for the primary sources found in this packet. Continue reading the packet to find images and text for each primary source. As of 2020, all of the following newspapers were still in existence. The Journal and Guide The Journal and Guide is a Black press newspaper located in Norfolk, Virginia. Founded in 1922, it was a weekly newspaper with a circulation of over 80,000 by the mid 1940s. The New York Amsterdam News The New York Amsterdam News, founded in 1909, is based in New York City. It was a weekly newspaper in the 1930s. In the 1940s, it changed its name to the New York Amsterdam Star-News and by 1945 had a circulation of over 65,000. The Chicago Defender The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905, is based in Chicago, Illinois. Along with The Pittsburgh Courier, it became one of the most prominent and influential newspapers of the Black press, with a national readership. Ida B. Wells, Langston Hughes, and Martin Luther King wrote columns printed in the paper. -

Passioned, Radical Leader Who Incorporating Their Own

Vol. 59 No. 11 March 13 - 19, 2019 CELEBRATING MARCH 14, 2018 25 Portland and Seattle Volume XL No. 24 CENTS BLACK MEN ARRESTED AT STARBUCKS WANT CHANGE IN U.S. RACIAL ATTITUDES - PG. 2 News ..............................3,8-10 A & E .....................................6-7 Opinion ...................................2 NRA Gives to Schools ......8 NATIONAL NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION CHALLENGING PEOPLE TO SHAPE A BETTER FUTURE NOW Calendars ...........................4-5 Bids/Classifieds ....................11 THE SKANNER NEWS READERS POLL Should Portland Public Schools change the name of Jefferson High School? (451 responses) YES THE NATION’S ONLY BLACK DAILY 129 (29%) NO Reporting and Recording Black History 322 (71%) STUDENTS WALK OUT 75 Cents VOL. 47 NO. 28 FRIDAY, APRIL 20, 2018 Final Seventy-one percent of respondents to a The Skanner News poll favored keeping the name of Thomas Jefferson High School intact. CENTER192 FOCUSES ON YOUTH POLL RESULTS: YEARS OF THE 71 Percent of TO HELP SAVE THE PLANET The Skanner’s Readers Oppose BLACK PRESS Jefferson Name Change Alumni association circulating a petition OF AMERICA opposed to name change PHOTO BY SUSAN FRIED SUSAN BY PHOTO By Christen McCurdy Hundreds of students from Washington Middle School and Garfield High School joined students across the country in a walkout and 17 minutes of silence Of The Skanner News to show support for the lives lost at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida Feb. 14 and to let elected officials know that they want stricter gun control laws. he results of a poll by The Skanner News, which opened Feb. 22 and closed Tuesday, favor keeping the Oregon Introduces ‘Gun Violence Restraining Orders’ Tname of North Portland’s Thomas Jefferson High School. -

Historical Black Newspapers to See History Being Made, Start Here

Historical Black Newspapers To see history being made, start here. proquest.com To talk to the sales department, contact us at 1-800-779-0137 or [email protected]. Essential primary source content and editorial perspectives of the most distinguished African American newspapers in the U.S. Each of the ten Historical Black Newspapers provides researchers with unprecedented access to perspectives and information that was excluded or marginalized in mainstream sources. The content, including articles, obituaries, photos, editorials, and more, is easily accessible for scholars in the study of the history of race relations, journalism, local and national politics, education, African American studies, and many multidisciplinary subjects. From coverage by the first black White House correspondent and stories on the cultural explosion of the Harlem Renaissance to exposure of, and arguments against, social injustice, these publications reveal history as it was being made, by the people who experienced it. THE NEED FOR NEWS In an era where local news coverage has been on the decline, historical regional papers can transport students and researchers to another time where smaller newspapers served as the informational hub of the community. Stories about neighborhood personalities, town events, city politics, schools, agriculture, commerce and other local business aren’t available anywhere else. Additionally, regional newspapers reveal local perspectives on national and international affairs for insight on how everyday lives are impacted and influenced by the issues and events that dominate the headlines of major metropolitan papers. 72% of researchers use news today A 2017 ProQuest study shows that newspapers are a vital tool in research – they’re used by 72% of researchers and recommended by 80% of researchers who teach. -

African American State Legislators and Civil Rights in Early Twenticth-Century Pennsylvania Eric Leddli Smith Parnqxswnmi Hsoriealand Mueum Commissieon

"Asking for Justice and Fair Play": African American State Legislators and Civil Rights in Early Twenticth-Century Pennsylvania Eric Leddli Smith PArnqxswnmi Hsoriealand Mueum Commissieon lk Who's WhD is CahwedAMNAM MM= On March 29, 1921, two African American state legislators urged the Penunsrlnia General Assembly to grant black Pennsylvanians full citizenship by passing an equal rights bill. John C. Asbury, a Republican representative from Philadelphia, spoke of his interracial upbringing in Washington County: As a boy, I played, studied, and fought with boys of other races ... I never received anything from those boys but justice and fair play. In the belief that Pansylvania men are just Pcnnsrivania boys grown older, I come to you asking for that sam justice and fair play.' 170 Pennsylvania History Republican Andrew Stevens Jr. of Philadelphia reminded his colleagues that it was Easter, a time to remember that Christ died so "that the sins of men might be redeemed-not white men, brown men or even yellow men or black men, but all men." Stevens argued that if all men have equal access to salvation, then all men are entitled to equal rights under the law. By this bill, Stevens said, blacks "demand full citizenship in Pennsylvania and these United States of America."2 The Pennsylvania House passed the Asbury Bill that day, but in April, 1921, the bill was defeated in the Senate. Fourteen years would pass before another black Pennsylvania legislator would introduce a civil rights bill. Scholarship on black Philadelphia political life has not intensively studied the first two decades of the twentieth century. -

A Dress Rehearsal for the Modern Civil Rights Movement: Raymond Pace

A DRESS REHEARSAL FOR THE MODERN CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT: RAYMOND PACE ALEXANDER AND THE BERWYN, PENNSYLVANIA, SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASE, 1932- 1935 Author(s): David Canton Source: Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 75, No. 2 (SPRING 2008), pp. 260-284 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27778832 Accessed: 18-12-2018 15:58 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27778832?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies This content downloaded from 108.31.134.250 on Tue, 18 Dec 2018 15:58:45 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A DRESS REHEARSAL FDR THE MODERN CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT: RAYMOND PACE ALEXANDER AND THE BERWYN, PENNSYLVANIA, SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASE, 1932-1935 David Canton Connecticut College n the front cover of the October i, 1957, issue of the Philadelphia Tribune, an African American newspaper, is an article on Arkansas 's Governor Oral Faubus's attempt to prevent nine black children from desegregating the all-white Central High School.