Introduction to Traditional Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pilot and Feasibility Study on the Effects of Naturopathic Botanical and Dietary Interventions on Sex Steroid Hormone Metabolism in Premenopausal Women

1601 A Pilot and Feasibility Study on the Effects of Naturopathic Botanical and Dietary Interventions on Sex Steroid Hormone Metabolism in Premenopausal Women Heather Greenlee,1 Charlotte Atkinson,2 Frank Z. Stanczyk,3 and Johanna W. Lampe2 1Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York; 2Cancer Prevention Program, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington; and 3Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Abstract Naturopathic physicians commonly make dietary and/or insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor dietary supplement recommendations for breast cancer binding protein-3, and leptin). Serum samples collected prevention. This placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, pilot during the mid-luteal phase of cycles 1 and 5 were analyzed study tested the effects of two naturopathic interventions for total estradiol, free estradiol, and sex hormone-binding over five menstrual cycles on sex steroid hormones and globulin. Urine samples collected during the late follicular metabolic markers in 40 healthy premenopausal women. phase of cycles 1 and 5 were analyzed for 2-hydroxyestrone The intervention arms were as follows: combination and 16A-hydroxyestrone. During the early follicular phase, botanical supplement (Curcuma longa, Cynara scolymus, compared with placebo, the botanical supplement decreased Rosmarinus officinalis, Schisandra chinensis, Silybum mar- dehydroepiandrosterone (À13.2%; P = 0.02), dehydroepian- inum, and Taraxacum officinalis; n = 15), dietary changes drosterone-sulfate (À14.6%; P = 0.07), androstenedione (3 servings/d crucifers or dark leafy greens, 30 g/d fiber, 1-2 (À8.6%; P = 0.05), and estrone-sulfate (À12.0%; P = 0.08). liters/d water, and limiting caffeine and alcohol consump- No other trends or statistically significant changes were tion to 1 serving each/wk; n = 10), and placebo (n = 15). -

Safe Management of Bodies of Deceased Persons with Suspected Or Confirmed COVID-19: a Rapid Systematic Review

Original research BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002650 on 14 May 2020. Downloaded from Safe management of bodies of deceased persons with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: a rapid systematic review 1 2,3 1 Sally Yaacoub , Holger J Schünemann, Joanne Khabsa , 1 4 1 Amena El- Harakeh, Assem M Khamis , Fatimah Chamseddine, Rayane El Khoury,1 Zahra Saad,5 Layal Hneiny,6 Carlos Cuello Garcia,7 Giovanna Elsa Ute Muti- Schünemann,8 Antonio Bognanni,7 Chen Chen,9 Guang Chen,10 Yuan Zhang,7 Hong Zhao,11 Pierre Abi Hanna,12 Mark Loeb,13 Thomas Piggott,7 Marge Reinap,14 Nesrine Rizk,15 Rosa Stalteri,7 Stephanie Duda,7 7 7 1,7,16 Karla Solo , Derek K Chu , Elie A Akl, the COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Reviews Group Effort (SURGE) group To cite: Yaacoub S, ABSTRACT Summary box Schünemann HJ, Khabsa J, Introduction Proper strategies to minimise the risk of et al. Safe management of infection in individuals handling the bodies of deceased bodies of deceased persons What is already known? persons infected with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019- nCoV) with suspected or confirmed There is scarce evidence on the transmission of are urgently needed. The objective of this study was to ► COVID-19: a rapid systematic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other systematically review the literature to scope and assess review. BMJ Global Health coronaviruses from the dead bodies of confirmed or the effects of specific strategies for the management of 2020;5:e002650. doi:10.1136/ suspected cases. bmjgh-2020-002650 the bodies. -

Indian System of Medicine

Ayurveda - Indian system of medicine Gangadharan GG, Ayurvedacharya, FAIP (USA), PhD, MoM (McGill, Canada) Director, Ramaiah Indic Specialty Ayurveda A unit of Gokula Education Foundation (Medical) New BEL Road, MSR Nagar, Mathikere PO, Bengaluru - 54 Tel: +91-80-22183456, +91-9632128544, Mob: +91- 9448278900 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.msricaim.com/ Introduction • Indian knowledge systems (IKS) – foundational unity despite diverse nature • Contiguous, interconnected and epistemologically common identity • Same thread runs through gamut of activities including medicine, farming, cooking, grammar, dance, arts etc. • Currently, IKS are in a state of transition owing to external influence • Unfortunately distorted promotion and popularization of IKS that can be detrimental to civilization in the long run Medical pluralism • Health behavior is a type of social behavior mainly influenced by the various socio-cultural issues. • Understanding a disease/illness is not a medical subject rather it is mainly reliant on the common information of the concerned community. • This has led to prevalence of more than one system of medicine existing • Medical Pluralism is an adaptation of more than one medical system or simultaneous integration of orthodox medicine with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) Traditional medicine • WHO defines traditional medicine is the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, -

Seeking and Plant Medicine Becomings

What if there is a cure somewhere in the jungle? Seeking and plant medicine becomings by Natasha-Kim Ferenczi M.A. (Anthropology), Concordia University, 2005 B.A. (Hons.), Concordia University, 2002 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Natasha-Kim Ferenczi 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Natasha-Kim Ferenczi Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: What if there is a cure somewhere in the jungle? Seeking and plant medicine becomings Examining Committee: Chair: Pamela Stern Assistant Professor Marianne Ignace Senior Supervisor Professor Dara Culhane Co-Supervisor Professor Ian Tietjen Internal Examiner Assistant Professor Faculty of Health Sciences Leslie Main Johnson External Examiner Professor Department of Anthropology Athabasca University Date Defended/Approved: December 10, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis is a critical ethnographic exploration of meanings emerging at the plant- health nexus and the in-between spaces when seekers and healers meet in efforts to heal across epistemological borderlands. In both British Columbia, Canada and Talamanca, Costa Rica I investigated the motivations underpinning seeking trajectories structured around plant medicine and the experiences and critical reflections on these encounters made by healers and people who work with plant medicines. In this dissertation, I expose the contested space around understandings of efficacy and highlight the epistemological politics emphasized by participants who seek to de-center plants in popular therapeutic imaginaries, to bring out these tensions and the way they interpolate ideas about sustainability and traditional knowledge conservation. -

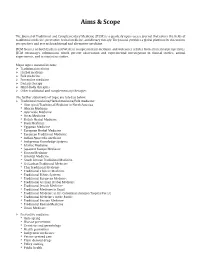

FM2- Aims & Scope

Aims & Scope The Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine (JTCM) is a quarterly open-access journal that covers the fields of traditional medicine, preventive herbal medicine, and dietary therapy. The Journal provides a global platform for discussion, perspectives and research traditional and alternative medicine. JTCM focuses on both Eastern and Western complementary medicine and welcomes articles from all medical perspectives. JTCM encourages submissions which present observation and experimental investigation in clinical studies, animal experiments, and in vivo/vitro studies. Major topics covered include: ¾ Traditional medicine ¾ Herbal medicine ¾ Folk medicine ¾ Preventive medicine ¾ Dietary therapy ¾ Mind-body therapies ¾ Other traditional and complementary therapies The further statements of topic are listed as below: ¾ Traditional medicine/Herbal medicine/Folk medicine: • Aboriginal/Traditional Medicine in North America • African Medicine • Ayurvedic Medicine • Aztec Medicine • British Herbal Medicine • Bush Medicine • Egyptian Medicine • European Herbal Medicine • European Traditional Medicine • Indian Ayurvedic medicine • Indigenous Knowledge Systems • Islamic Medicine • Japanese Kampo Medicine • Korean Medicine • Oriental Medicine • South African Traditional Medicine • Sri Lankan Traditional Medicine • Thai Traditional Medicine • Traditional Chinese Medicine • Traditional Ethnic Systems • Traditional European Medicine • Traditional German Herbal Medicine • Traditional Jewish Medicine • Traditional Medicine in Brazil -

Click to View File (PDF)

www.ajbrui .org Afr. J. Biomed. Res. Vol. 23 (January, 2020); 111- 115 Research Article Perspectives on the Concurrent Use of Traditional and Prescribed Antimicrobial Medicines for Infectious Diseases: A Triangulation Study in a South African Community *Kadima M.G., Mushebenger A.G and Nlooto M Discipline of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu –Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa. ABSTRACT Traditional medicines are generally available, affordable and commonly used as self-care treatments. However, their inaccurate utilization can results in adverse events, or unfavourable outcomes. Individuals may consult both traditional healer practitioners (THPs) and biomedically trained healthcare professionals (BHPs) for their infections. This study aimed at determining whether any antimicrobial resistance and treatment failure could occur among patients, attending outpatient departments of selected healthcare facilities, who used concurrently prescribed antimicrobial and traditional medicines. A survey was conducted to assess the perceptions, knowledges, attitudes and beliefs of respondents on the concurrent use of traditional and prescribed medicines for infections. 132 respondents were included namely THPs, THP’s patients, BHPs and BHP’s outpatients. A small number of medicinal plants were used in the treatment of infections and 65.62% of both THPs and their patients (21/32) reported mixing different herbs for the treatment of infections. Respondents agreed that the combination of traditional and prescribed medicines -

How Traditional Healers Diagnose and Treat Diabetes Mellitus

https://www.scientificarchives.com/journal/archives-of-pharmacology-and-therapeutics Archives of Pharmacology and Therapeutics Review Article How Traditional Healers Diagnose and Treat Diabetes Mellitus in the Pretoria Mamelodi Area and How Do These Purported Medications Comply with Complementary and Alternative Medicine Regulations Ondo Z.G.* Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa *Correspondence should be addressed to Ondo ZG; [email protected] Received date: August 13, 2019, Accepted date:September 18, 2019 Copyright: © 2019 Ondo ZG. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Background: In South Africa, new amended regulations required a review of complementary and alternative medicine (CAMs) call-up for registration from November 2013. This impacted traditional healers (THs)’ compliance with the regulatory authorities’ on the good manufacturing practice which in return affected the public’s access to CAMs. This investigation embraces methods, THs use to diagnose and treat diabetes (DM) in Mamelodi. Furthermore, it assesses what their purported medications comprise of. It is fundamental to understand the functioning of the South African Health Products Regulatory Agency (SAHPRA). Regulations surrounding registration and post-marketing control of CAMs are crucial, needing a solution. Method: The study comprised of dedicated questionnaires, distributed amongst THs to gain knowledge on their diagnosis and identify the CAMs used. It also included non-structured surveys on pharmacies to identify and assess compliance of those CAMs with the SAHPRA (previously Medicines Control Council (MCC)) regulations. -

Understanding Complementary Therapies a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Treatment For information & support, call Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published October 2008. This edition April 2018. © Cancer Council Australia 2018. ISBN 978 1 925651 18 8 Understanding Complementary Therapies is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date. Editor: Jenny Mothoneos. Designer: Eleonora Pelosi. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Cancer Information Working Group initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: Suzanne Grant, Senior Acupuncturist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; A/Prof Craig Hassed, Senior Lecturer, Department of General Practice, Monash University, VIC; Mara Lidums, Consumer; Tanya McMillan, Consumer; Simone Noelker, Physiotherapist and Wellness Centre Manager, Ballarat Regional Integrated Cancer Centre, VIC; A/Prof Byeongsang Oh, Acupuncturist, University of Sydney and Northern Sydney Cancer Centre, NSW; Sue Suchy, Consumer; Marie Veale, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council Queensland, QLD; Prof Anne Williams, Nursing Research Consultant, Centre for Nursing Research, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, and Chair, Health Research, School of Health Professions, Murdoch University, WA. We also thank the health professionals, consumers and editorial teams who have worked on previous editions of this title. This booklet is funded through the generosity of the people of Australia. Note to reader Always consult your doctor about matters that affect your health. This booklet is intended as a general introduction to the topic and should not be seen as a substitute for medical, legal or financial advice. -

Understanding Complementary Therapies a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Treatment www.cancerqld.org.au Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published October 2008. This edition June 2012. © The Cancer Council NSW 2012 ISBN 978 1 921619 67 0 Understanding Complementary Therapies is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy of the booklet is up to date. To obtain a more recent copy, phone Cancer Council Helpline 13 11 20. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Publications Working Group Initiative. We thank the reviewers of this edition: Dr Vicki Kotsirilos, GP, Past founding president of Australasian Integrative Medicine Association, VIC; Annie Angle, Cancer Council Helpline Nurse, Cancer Council Victoria; Dr Lesley Braun PhD, Research Pharmacist, Alfred Hospital and Integrative Medicine Education and Research Group, VIC; Jane Hutchens, Registered Nurse and Naturopath, NSW; Bridget Kehoe, Helpline Nutritionist, Cancer Council Queensland; Prof Ian Olver, Chief Executive Officer, Cancer Council Australia, NSW; Carlo Pirri, Research Psychologist, Faculty of Health Sciences, Murdoch University, WA; Beth Wilson, Health Services Commissioner, VIC. We are grateful to the many men and women who shared their stories about their use of complementary therapies as part of their wider cancer care. We would also like to thank the health professionals and consumers who worked on the previous edition of this title, and Vivienne O’Callaghan, the orginal writer. Editor: Jenny Mothoneos Designer: Eleonora Pelosi Printer: SOS Print + Media Group Cancer Council Queensland Cancer Council Queensland is a not-for-profit, non-government organisation that provides information and support free of charge for people with cancer and their families and friends throughout Queensland. -

Aboriginal Healing Practices and Australian Bush Medicine

Philip Clarke- Aboriginal healing practices and Australian bush medicine Aboriginal healing practices and Australian bush medicine Philip Clarke South Australian Museum Abstract Colonists who arrived in Australia from 1788 used the bush to alleviate shortages of basic supplies, such as building materials, foods and medicines. They experimented with types of material that they considered similar to European sources. On the frontier, explorers and settlers gained knowledge of the bush through observing Aboriginal hunter-gatherers. Europeans incorporated into their own ‘bush medicine’ a few remedies derived from an extensive Aboriginal pharmacopeia. Differences between European and Aboriginal notions of health, as well as colonial perceptions of ‘primitive’ Aboriginal culture, prevented a larger scale transfer of Indigenous healing knowledge to the settlers. Since British settlement there has been a blending of Indigenous and Western European health traditions within the Aboriginal community. Introduction This article explores the links between Indigenous healing practices and colonial medicine in Australia. Due to the predominance of plants as sources of remedies for Aboriginal people and European settlers, it is chiefly an ethnobotanical study. The article is a continuation of the author’s cultural geography research that investigates the early transference of environmental knowledge between Indigenous hunter- gatherers and British colonists (1994: chapter 5; 1996; 2003a: chapter 13; 2003b; 2007a: part 4; 2007b; 2008). The flora is a fundamental part of the landscape with which human culture develops a complex set of relationships. In Aboriginal Australia, plants physically provided people with the means for making food, medicine, narcotics, stimulants, 3 Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia Vol. -

Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Author(S): Marsha B

Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Author(s): Marsha B. Quinlan and Robert J. Quinlan Source: Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 2007), pp. 169- 192 Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4499720 Accessed: 23-01-2018 22:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms American Anthropological Association, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Medical Anthropology Quarterly This content downloaded from 69.166.46.145 on Tue, 23 Jan 2018 22:34:18 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Marsha B. Quinlan Department of Anthropology Washington State University Robert 3. Quinlan Department of Anthropology Washington State University Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Herbal medicine is the first response to illness in rural Dominica. Every adult knows several "bush" medicines, and knowledge varies from person to person. Anthropo- logical convention suggests that modernization generally weakens traditional knowl- edge. We examine the effects of commercial occupation, consumerism, education, parenthood, age, and gender on the number of medicinal plants freelisted by indi- viduals. -

AJHM Vol 24 (4) Dec 2012

Volume 24 • Issue 4 • 2012 Herbal Medicine A publication of the National Herbalists Association of Australia Australian Journal national herbalists of Herbal association of australia Medicine The Australian Journal of Herbal The NHAA was founded in Full ATSI membership Medicine is a quarterly publication of 1920 and is Australia’s oldest Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners who have undertaken formal the National Herbalists Association of national professional body of studies in bush medicine and Western herbal Australia. The Journal publishes material herbal medicine practitioners. medicine. on all aspects of western herbal medicine The Association is a non profit member Annual fee $60 and a $5 joining fee. and is a peer reviewed journal with an based association run by a voluntary Student membership Editorial Board. Board of Directors with the help of Students who are currently undertaking interested members. The NHAA is studies in western herbal medicine. Members of the Editorial Board are: involved with all aspects of western Annual fee $65 and a $10 joining fee. Ian Breakspear MHerbMed ND DBM DRM herbal medicine. Companion membership PostGradCertPhyto The primary role of the association is to Companies, institutions or individuals Sydney NSW Australia support practitioners of herbal medicine: involved with some aspect of herbal Annalies Corse BMedSc(Path) BHSc(Nat) medicine. Sydney NSW Australia • Promote, protect and encourage the Annual fee $160 and a $20 joining fee. Jane Frawley MClinSc BHSc(CompMed) DBM study, practice and knowledge of GradCertAppSc western herbal medicine. Corporate membership Blackheath NSW Australia • Promote herbal medicine in the Companies, institutions or individuals Stuart Glastonbury MBBS BSc(Med) DipWHM community as a safe and effective interested in supporting the NHAA.